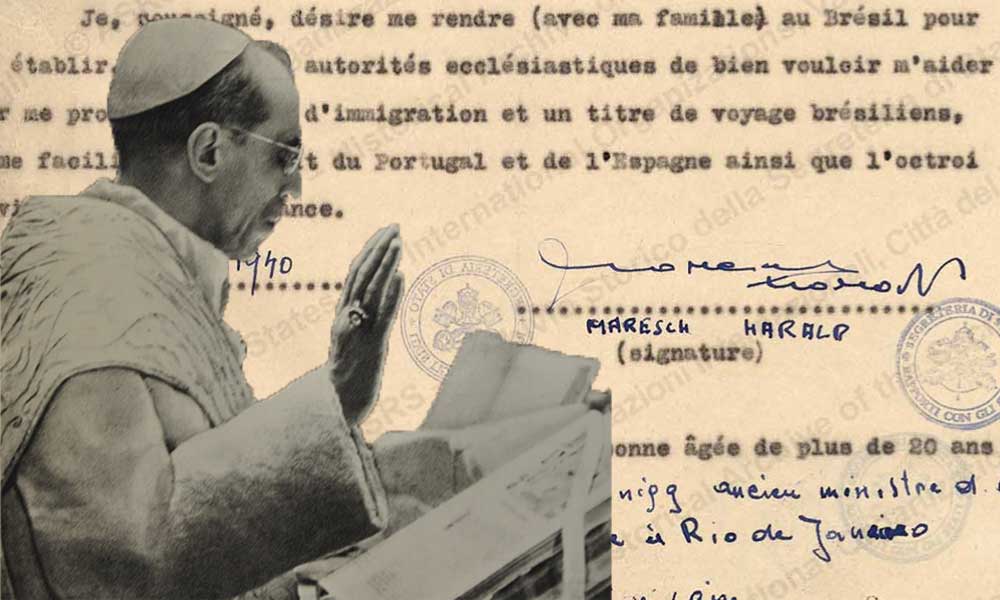

On April 24, 1940, Arthur Pick typed out a letter in crisp black ink and sent it to the Vatican. In the letter, which can now be read on the Vatican library website, he requested help from the pope in securing permission for both him and his wife, Pauline, to flee Italy and enter Brazil. While they were both of the Catholic faith, both had Jewish fathers and were classified as mixed race under Italian law. In his letter (translated from Italian), he writes, “Thanks to the goodness of Reverend Monsignor [Maino], I have been given the attached recommendation to which I permit myself to join my deep and devoted prayer in order that Your Excellency may benevolently care to extend to me and my wife His help to make it possible for us to immigrate to Brazil.”

After no response, Pick typed out another letter, in blue ink, referring to his prior correspondence. Again, he emphasized his need for visas, explaining that while he and his wife are both devout Catholics, their half-Jewish status puts them in danger. He mentioned his skills, explaining that he was a gardener and tractor driver and had additional experience in electrical work. In subsequent correspondence, Pick included an additional recommendation letter from Reverend Monsignor Maino.

On August 31, 1940, Pick sent yet another letter, this time in scribbled handwriting. It opened (translated from Italian), “I beg you to take into consideration my letter from today and I permit myself to mention that I have already sent you up until now two letters of recommendation from Monsignor Maino and I am still waiting for a kind and favorable response.”

These letters are a few of the thousands recently disentombed from Vatican archives and shared with the general public. In 2020, this collection was made available to scholars, but only in June did the Vatican add a new series, entitled “Ebrei,” or “Jews,” to their publicly accessible online database.

Anyone with a computer can now access the 170 files and nearly 40,000 volumes containing letters that Jews wrote to Pope Pius XII (the correspondence dates from 1939 to 1948) during World War II asking for help. Letters consisting of requests for visas and asylum, information about deported family members and release from detention centers can all be found in the database. In an article published to Vatican News, the Secretary for Relations with States and International Organizations, Archbishop Paul Richard Gallagher writes, “Making the digitized version of the entire ‘Ebrei’ series available on the internet will allow the descendants of those who asked for help to find traces of their loved ones from any part of the world. At the same time, it will allow scholars and anyone interested to freely examine this special archival heritage from a distance.”

The conversation surrounding the Vatican’s exact role during the Holocaust has a long and volatile history. Pulitzer-Prize-winning author and historian David Kertzer, who has spent a large part of the last 25 years writing books on the history of the Vatican related to World War II based on archival material, says this is not the first time the Vatican has released previously undisclosed documents. Starting in 1963, the Vatican began releasing an 11-volume collection of the pontiff’s wartime documents after a German play titled The Deputy, about the Vatican’s silence during the Holocaust, led to intense criticism from the general public. When it comes to deciding to release documents, the Vatican operates differently than other archival systems.

“Generally state archives and other kinds of archives have a rule that a certain number of years have to pass before they’ll open the material,” says Kertzer. “But the Vatican doesn’t work that way.” Previously unopened archives are divided by papacy and when they are released, everything in the papacy is released at once. The current pope decides when to open these documents.

When the Vatican does decide to release archival documents, it is usually reserved solely for historians and scholars who need to to apply for access. Kertzer noted that the Vatican is most likely releasing it to the general public to take control of the narrative surrounding Pius XII. In June of this year, Kertzer released his new book titled, The Pope At War, about Pope Pius XII and his actions during World War II. This book takes a critical look at the actions the pope did and didn’t take during the war.

“The new book came out in Italy at the end of May a couple of weeks before it came out in the United States. It immediately provoked a strong attack from the Vatican.” The Vatican hopes that these archives from World War II will put Pius XII in a more positive light and show that he did all he could to save Jews.

The Vatican’s heroic narrative has been the main cause for criticism over the years. Its official line and that of many conservatives within the church is that the pope’s silence during the Holocaust actually helped save many lives, says Kertzer. If Pius XII had spoken out, it would have resulted in more Jewish deaths; by staying silent, he was able to work behind the scenes to save them.

“What’s known and can’t be denied is that the pope never denounced the Nazis,” Kertzer contends. “In trying to justify the racial laws in Italy, the fascist regime made heavy use of the church.” Prior to the facist takeover, Italy did not have many antisemitic laws or measures. The facist regime justified these new racial laws by comparing it to the time when the pope had rule over the papal states and Jews were barred from certain professions and social circles.

Still, there is much to garner from the thousands of pages of newly released evidence. A noteworthy discovery is that a majority of the pleas are in fact from Catholics, not Jews. They are baptized Jews or descendents of Jews who ultimately identify as Catholic. Even so, they are being affected by the country’s racial laws and potential deportation and extermination due to their Jewish status.

“What I see in these - Five Jewish Horror Movies to Watch at Halloween

- A Charming Children’s Book Emerges From the Devastation of October 7

- From the Newsletter | The Strongman in America

- A Wide Open Conversation with Senator Ben Cardin

- Jewish Word | Mazel Tov! A Toast to Astrology?

- The Past, Present and Future of the Israel-Jordan Relationship

- Ain’t No Back to a Merry-Go-Round: The Little-Known Story of a Segregated Amusement Park with Ilana Trachtman and Dan Freedman

- Interview | Ghaith al-Omari on the End of the Sinwar Era and What Comes Next

- The End of the Sinwar Era: What Comes Next? with Ghaith al-Omari and Nadine Epstein

- Breaking News | Hamas Leader Yahya Sinwar Killed in Gaza

- The End of the Sinwar Era: What Comes Next? with Ghaith al-Omari and Nadine Epstein

- ‘Nobody Wants This’ Has Rubbed Many Jews the Wrong Way. They’re Missing the Point

- The View from Jordan Amidst Middle East Turmoil with Taylor Luck and Nadine Epstein

- ‘Tis the Season to Reach Out to Jewish Voters

- Interview | Phyllis Greenberger, Author of ‘Sex Cells: The Fight to Overcome Bias and Discrimination in Women’s Healthcare’

- From 1984 | Home (Plate) for the Holidays

- From 2004 | Break-Fast on Cyprus

- The Vast and Tangled Roots of Christian Nationalism, White Supremacism and Antisemitism with David Morrison and Nadine Epstein

- Wisdom Project | Charlotte Goode, 97, a Woman Who Supports Women

- What American Jews and Muslims Can Learn from One Another with Samuel Heilman, Mucahit Bilici, Sarah Breger and Zainab Khan

- Opinion | How We in Israel Tried to Commemorate October 7

- From 2006 | The Shiksa Revival

- Opinion | UN Secretary General António Guterres Unworthy of Nobel Peace Prize

- The Conversation

- Book Review | With Critics Like These, Israel Will Be Fine

- Spice Box | Certified by the Orthodox Moonion

- Book Review | Kiss Me, I’m Irish and Jewish!

- Book Review | The Young, the Rich and the Guilty

- Q&A | The War in Lebanon with Hanin Ghaddar

- A Day of Love & Darkness

- The Iran-Israel Face-Off with Roya Hakakian and Nadine Epstein

- The Iran-Israel Face-Off with Roya Hakakian and Nadine Epstein

- What Is Zionism?

- Jimmy Carter: The Great “Jewish” President with Stuart Eizenstat and Nadine Epstein

- B’Ivrit | The Elimination of Hassan Nasrallah

- Visual Moment | The Little Boat that Could: Resistance and Rescue in Denmark

- Talk of the Table | The Stew of Seven Tastes

- The Israel-Hezbollah Showdown: Key Takeaways

- Poem | “Leadership”

- Ask the Rabbis | Is God the Ultimate Strongman?

- Moment Debate | Can Jews Ever Flourish Under Authoritarians?

- The Fight to Save the Hostages Isn’t Over with Vered Guttman and Jennifer Bardi

- The Israel-Hezbollah Showdown: What’s happening inside Israel, Lebanon, Gaza, Jordan and Iran with Aaron David Miller and Nadine Epstein

- Fighting Antisemitism…with Antisemitism?

- Fighting Antisemitism…with Antisemitism?

- A Rare View of Chagall’s Decorative Arts

- The Israel-Hezbollah Showdown: What’s Happening Inside Israel, Lebanon, Gaza, Jordan and Iran with Aaron David Miller and Nadine Epstein

- The Covenant Between God and Humanity with Rabbi Irving Greenberg and Amy E. Schwartz

- Big Question | What Is the Allure of the Strongman?

- Interview | To & Fro Is a Conversation between Kafka and Midrash

- Lochs and Bagels: A Trip to Jewish Scotland

- When Miriam Calls

- From the Newsletter | Paris 1874: The Impressionist Moment

- The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others with Elissa Strauss and Sarah Breger

- JPVP Roundup | Is the Roller Coaster Rider Nearing an End?

- Opinion | How Long Does a War Take?

- Opinion | I’m Done With Concessions

- Opinion | How We in Israel See Your Election

- Opinion | Yehuda Kurtzer On The New Jewish Divide

- Jewish Word | ‘Momala’ of the Year

- From the Editor | Staring Down An Unknown Future

- Deborah Pardes: I’m Not a One Issue Voter

- Jaclyn Best: Will Kamala Change Policy on Israel?

- Josh Mandelbaum: Trump’s Negativity

- Abby Schachter: A Foreign Policy Election

- Leah Kiser: A Trump Election Would Mortally Wound Democracy

- Deb Kolodny: Hopeful for the Democratic Agenda

- Eva R. Cohen: Positive and Forward-Looking

- Adam Witkov: Undecided, but Definitely Not Trump

- Diana Leygerman: Trump Would be a Disaster for American and for Israel

- Meirav Solomon: Harris the Only Choice on Israel

- Don Cohen: Trump is a Nonstarter

- David Wolkinson: Concerns About Kamala Over Israel

- Chesky Blau: A Different Roller Coaster

- Nina Stanley: Democracy on the Ballot

- Jeff Michaels: Reluctantly Voting for the Democratic Ticket

- Aaron Weissman: Democracy on the Brink

- Memoir | Set in Stone, Stumbling Home

- Premier Eight Prime Matchmaking Websites as well as Programs at the U.S.

- A Wide-Open Conversation with Robert Klein and Joe Alterman

- Reinventing Black-Jewish Relations: Learning from the Past and Embracing the New with Marc Dollinger, Eric K. Ward and Nadine Epstein

- What to Watch for in the Harris-Trump Debate

- Jewish Film Review | ‘Between the Temples’

- Israel, Lebanon and Hezbollah with Hanin Ghaddar, Aaron David Miller and Robert Siegel

- Who Was Jacob de Haan?

- B’Ivrit | Rumors, Whatsapp and Military Censorship

- Cori Bush, AIPAC and the Future of Black-Jewish Relations

- Opinion | Bibi’s Cold Calculation

- Wisdom Project | Philip Drill, 97, on Sculpting a Moral Life

- Book Review: The Double Life of a Female Jewish Crime Boss

- What it Takes to Grow a “Badass Woman” Journalist with CNN’s Dana Bash and her mother Francie Weinman Schwartz

- From Yeshiva to Court-Martial to Columbia Cease-Fire Cause

- For Jewish Students, Back to School Brings Hesitation and Hope

- Moment Goes to the 2024 DNC

- The Enduring Jewish Legacy at the Paralympics

- The GOP’s “Weirdness,” the Jewish vote and the DNC

- Harris-Walz Waltz Shines Spotlight on Holocaust Education

- No, Chappell Roan Is Not Jewish

- From the Newsletter | Could Retaliatory Attack Arrive on Tisha B’Av?

- Analysis | After a Historic Exchange of Prisoners, What’s Next?

- Tisha B’Av and its Ripples Today

- The Story of JVP, a Divisively Jewish Voice for Peace

- B’Ivrit | Israeli Media Analyzes Different Reactions to Terrorist Assassinations

- Sarah Levy Isn’t the First Jewish Rugby Player at the Olympics

- Swaps, Assassins and What Comes Next

- Ask the Rabbis | How Do We Balance Civility With Disapproval For Others’ Politics?

- What Should We Call the Golan Heights?

- Not Your Father’s Jewish Mother with Rebecca Goldstein, Yael Goldstein-Love and Amy E. Schwartz—in celebration of the Moment-Karma Short Fiction Contest

- Spice Box | Own it

- Poem | PRISONER Z

- The Conversation

- Assessing Netanyahu’s Not-So-Great DC Trip

- Ushi Teitelbaum: Democratic Excitement Over Kamala

- Looking for a Middle Around the Edges of Bibi’s Visit

- Overnight Shift

- The Sound that Turtles Make

- Book Review | Is Motherhood Bigger Than Reality?

- Visual Moment | Camille Pissarro and the Birth of Impressionism

- Jeff Michaels: Trump Going After Establishment Elites

- Nina Stanley: I Feel Invigorated

- Chesky Blau: Trump Will Pull Through in the End

- Aaron Weissman: Democrats’ Chances Go Up

- JPVP Roundup | Biden Drops Out

- Israel: Voices and Visions

- A Jewish Primer on Kamala + Biden meets Bibi

- Treva Silverman, Joke Whisperer

- Wisdom Project | Annette Lerner, 94, Is Ready for Her Next Artistic Adventure

- Live From Tamiment

- Book Review | Love and Fear Drove a Dogged TV Pioneer

- The Laugh

- Samer Sanijlawi Knows Israelis “Better Than They Know Themselves”

- Summer Reads for Sun—and Shade

- Six Days Without Waze

- From the Editor | Searching for Our Ben-Gurion and Jabotinsky

- Opinion | Is Antisemitism Eternal?

- Moment Debate | Who Do You Think Would Make a Better President—Biden or Trump?

- Opinion | A ‘Mixed’ Marriage, a Lifelong Journey

- The Art of Diplomacy in a Fragile World with Stuart E. Eizenstat and Amy E. Schwartz

- From the Margins to the Mainstream

- B’Ivrit | Israeli Dailies Pounce on Biden’s Lackluster Debate Performance

- JPVP Roundup | Trump’s Trials and Biden’s Tribulations

- Opinion | Jewish Anti-Zionists, Check Your Privilege

- Opinion | A Deportation Policy With Chilling Echoes

- Book Review | Noah Feldman Explains Us To Ourselves

- Opinion | Is the Christian Right Coming for Birth Control?

- Jewish Word | Verklempt: The Yiddish Word that Wasn’t

- Adam Witkov: We’re Talking Out of Both Sides of Our Mouth on Israel

- Ushi Teitelbaum: Biden Needs to Go

- Chesky Blau: Someone Other Than Biden

- Diana Leygerman: Judicial Overreach

- Abby Schachter: The Court Isn’t Overstepping

- Nina Stanley: Biden Should be Replaced

- Aaron Weissman: Nobody Cares About the Presidential Race

- Talk of the Table | Hot Diggity Dog!

- Wisdom Project | Reggie Schatz, 98, Says “Family Is Everything”

- Was the Awful Presidential Debate Somehow Good for Israel?

- From Craigslist to Philanthropist: A Wide Open Conversation with Craig Newmark and Robert Siegel

- In Berlin, Some Israeli Ex-Pats Organize Against Germany’s Support for Israel

- From Craigslist to Philanthropist: A Wide Open Conversation with Craig Newmark and Robert Siegel

- A Legal Earthquake: Israel’s Supreme Court Decides that the Ultra-Orthodox Must Serve in the Military with Eetta Prince-Gibson and Nadine Epstein

- Jewish World War II Soldier Finally Rests In Peace

- From the Newsletter | Squeezing More Juice out of the Lemon Test

- Jewish Identity in a Post October 7 World with Sarah Hurwitz and Amy E. Schwartz

- Book Review | Making Music Was The Best Revenge

- Countdown to Netanyahu’s Speech

- From Jewish Rapper to Israel Activist with Kosha Dillz and Joe Alterman

- Craig Newmark on Safeguarding Independent Journalism and Democracy

- Analysis | We Need To Talk About Willful Ignorance

- My Life in Recipes with Joan Nathan and Robert Siegel Zoominar

- Nightingale of Iran with Danielle and Galeet Dardashti and Jennifer Bardi

- Avoiding Sleep on Shavuot: An Act of Denying Wisdom

- B’Ivrit | Desperate for Some Good News, Israelis Cling to Heroic Hostage Rescue Story

- Seven Species Salad & other Shavuot Specialties with Vered Guttman Zoominar

- Ayal Feinberg Connects Hate and War

- Mister Kelly’s Nightclub with David Marienthal, Alison Hinderliter and Joe Alterman

- Hate and War: A Stark Correlation

- Moment Wins 19 Rockower Awards at American Jewish Press Association’s 24th Annual Celebration of Jewish Journalism

- What We Need Is a Brazen Type of Love

- The Double Bind of Israelis on Campus

- My Life in Recipes with Joan Nathan and Robert Siegel

- Decision Time in the Middle East

- A Zoom Room With A View: One Man’s Window Into A Rafah Refugee Camp

- Claudia Sheinbaum: Trailblazer or Mexico’s Next Puppet Leader?

- The Many Sounds of Matisyahu Zoominar

- Nightingale of Iran with Danielle and Galeet Dardashti and Jennifer Bardi

- The International Criminal Court Requests Netanyahu’s Arrest

- Interview | Why An Atheist Wrote His Debut Novel About a Religious Family

- Opinion | Why I’m Boycotting My 50th Harvard Reunion

- From the Newsletter | Is the GOP’s Grilling of College Presidents Tantamount to McCarthyism?

- The Many Sounds of MATISYAHU with Matisyahu and Joe Alterman

- Campus Protests in the Voices of the Students Who Experienced Them

- Making Art in Times of Conflict with Alliance for Jewish Theatre

- Could Gallant and Gantz Deliver for Biden?

- Jack Ruby: The Many Faces of Oswald’s Assasin

- Everyday Israel with Joel Chasnoff, Benji Lovitt and Sarah Breger

- Don Cohen: People Aren’t Thinking About The Election Yet

- Deborah Pardes: News Without Substance

- Letter from Berkeley | What Do Campus Encampment Protesters Really Want?

- B’Ivrit | The Israeli Press Doesn’t Know What to Do About Biden

- Analysis | Chutzpah Gone Viral: Why Israel Produces So Many Cyber Leaders

- If These Walls Could Talk: Columbia’s Hamilton Hall—1968-2024 with Glenn Frankel, Robert Siegel, Susan Rubin Suleiman and Amy E. Schwartz

- Opinion | Why I Cannot Celebrate Mother’s Day 2024 in New York City

- Interview | Aviva Kempner’s ‘A Pocketful of Miracles’

- Ask the Rabbis | Can You Be Disqualified From Being a Jew?

- The Muses of October 7

- Five Players in the Campus Protest Showdown

- From the Newsletter | A Visit to the GW Protest Encampment

- Opinion | Silencing Criticism in the Name of Antisemitism Awareness

- Is McCarthyism Alive and Well on Capitol Hill?

- Israel Today: A Wide-Open Conversation with Yossi Klein Halevi and Amy E. Schwartz

- Verdi’s Nabucco in the Aftermath of October 7

- Jewish and Palestinian Teens Write—and Brave the United States—Together

- Opinion | What’s Wrong with This Picture?

- A Jewish Activist Remembers Surviving a Bombing Raid in Nazi Germany

- Survivors of the Nova Music Festival Dance, Honor and Heal

- The Mystery of the Cairo Codex: On the Trail of an Ancient Manuscript

- From the Newsletter | Moment Wins First Place from Religion News Association!

- Poem | The Leaves

- The Conversation

- Would You Send Your Jewish Child to a U.S. College?

- Spice Box | L’door-to-Door

- The New World of Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism on Campus with Sarah Breger, Sharon Nazarian and Amy E. Schwartz

- The Grace of Photographer Osnat Ben Dov’s “Shadow of a Passing Bird”

- Seven Modern Additions to the Seder Plate

- Antisemitism and Iranian Influence in the Americas

- Israel, Iran and the Dangers of a Wider War with Aaron David Miller, Robin Wright, and Robert Siegel

- Jeff Michaels: Concerned About America’s Economy

- Introducing the 2024 Jewish Political Voices Project

- Jaclyn Best: Walking on Eggshells Over Palestine

- Chesky Blau: Leaning Away From a Democratic Vote

- The U.S. Constitution: Pragmatism versus Textualism on the Supreme Court with Justice Stephen Breyer and Robert Siegel

- Susan Rupright: May Not Vote for President

- Jeff Solomon: October 7 Increased his Support of Biden

- Josh Mandelbaum: Continued Support for Biden

- Leah Kiser: Concerned About Women’s Rights

- Ushi Teitelbaum: Longing for Economic Stability

- Diana Leygerman: Against Censorship in Schools

- Abby Schachter: Wanting More College Involvement in Society

- Meirav Solomon: Biden is the Only Moral Answer

- Aaron Weissman: Fighting for Democracy

- David Guttenberg: Becoming a Zionist

- Deborah Pardes: Becoming a One-Issue Jewish Voter

- Don Cohen: More Security is Needed for Jews

- Nina Stanley: “This could be our last election”

- Deb Kolodny: Recognizing a Climate Catastrophe

- Adam Witkov: Saddened by the Lack of Jewish Support

- Eva R. Cohen: A Lack of Empathy for Civilians on Both Sides

- Iran Tests the U.S.-Israel Alliance

- Talk of the Table | The Versatile, Vengeful, Volatile Onion

- Book Review | An Ancient Book Illuminates Our Troubled Times

- Book Review | Ukraine’s Zelensky, Warts and All

- David Wolkinson: Prioritizing National Security

- Connecting Jewish Identity with Jewish Values with Donniel Hartman and Sarah Breger

- Letter From Dearborn | Scenes From the Heart of Arab America

- Opinion | At Israeli Seders, Pick Your Pharaoh

- Jewish Word | Doikayt: The Jewish Left Is Here

- Opinion Interview with Daniel Klaidman | Are Threats Eroding Our Politics?

- Visual Moment | Depicting Devastation

- B’Ivrit | Israeli Media Covers Anniversary of a Half-Year at War

- Moment Debate | Should UNRWA be shut down?

- From the Newsletter | Israel Is Not the Same: Notes From a Recent Trip

- Interview | Non-Orthodox Conversion in Israel

- Explainer | Will Israel Draft ‘Those Who Toil in Torah’?

- From the Editor | How Nuance Can Save Us

- Opinion | Carrying Navalny’s Torch

- Opinion | Israel’s Elusive ‘Day After’

- Esther Coopersmith

- For the Love of Judaism with Shai Held and Amy E. Schwartz

- Wisdom Project | Joseph Werk, 97

- Never Let a Good Crisis Go to Waste

- Beyond Greening: Jewish Responses to Climate Emergency

- Is a Two-State Solution for Israelis and Palestinians Still Possible? with Aaron David Miller, Ghaith al-Omari and Robert Siegel

- Israel’s Internal War

- Female, Funny and Fabulous with Felicia Madison, Ellen Sugarman and Jennifer Bardi

- What Do Students Want? UK Antisemitism and More

- Interview | Franklin Foer on the Golden Age of American Jews

- The Israeli Diaspora Finds A Voice

- How to Remember: Holocaust Literature From Survivors’ Accounts to 3G

- From 1975 | “Remembering,” by Elie Wiesel

- In Israel and Beyond, Hostages Freed by Hamas Share Their Stories

- Analysis | After October 7, Holocaust Literature Will Never Be the Same

- It’s not a Conspiracy: The Jewish and Black Origins of the Skinhead Movement with Jacob Kornbluth, Eric K. Ward, Pan Nesbitt and Nadine Epstein

- Is Chuck Schumer Playing Bad Cop for Biden?

- Diana Leygerman

- Why You Should Stop Being Angry at RBG

- Am I The Schmuck?

- B’Ivrit | Haredim, Gaza Coverage, Eurovision

- The Solar Eclipse Then and Now—the Jewish Perspective

- The Spirituality of Showing Up when it Matters with Sharon Brous and Amy E. Schwartz

- From Jewish Rapper to Israel Activist with Kosha Dillz and Joe Alterman

- Putin and the Killing of Alexei Navalny with Paul Goldberg and Amy E. Schwartz

- Clocks Are Ticking on a Cease-Fire Deal

- Wisdom Project | Morris Waitz, 100, Keeps Thinking About Tomorrow

- Audience & Antisemitism: February Round-Up

- Analysis: For South Africans, the ICJ Case is a “Reawakening”

- What Does Winning Look Like for Israel? with Eetta Prince-Gibson and Sarah Breger

- Class Dismissed: An Interview with Jewish Studies Professor Jeffrey Blutinger

- A Cooling: Jewish-Muslim Interfaith Work after October 7 and Gaza

- From 2005 | Breaking the Barrier: A Look at All Peace Radio

- Six Israeli/Palestinian Peace Projects Active Since October 7

- From the Editor’s Desk: A Podcast for Those in Search of Nuance

- Podcasts for Peace: Six Shows That Feature Nuanced Conversations about Israel/Palestine

- The Political Is Personal with Letty Cottin Pogrebin and Sarah Breger

- Can Pro-Israel Democrats Throw Biden a Lifeline?

- Opinion | What I Learned from Alexei Navalny

- Analysis | The Killing of Navalny and Putin’s Theater of Terror

- Analysis | What Could Winning This War Look Like?

- What Israelis Are Reading

- A Vision of Decency and Hope: Why James McBride Is Today’s Charles Dickens

- From Theodor Herzl to David Ben-Gurion: Humanist Zionism Lives on Today with Fania Oz-Salzberger and Sarah Breger

- A Human Lens: Teaching the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict Through Film

- Q&A | Genocide Scholar Mike Brand on the ICJ Ruling

- Profile | Is Aharon Barak Still Israel’s Most Maverick Judge?

- Explainer | Will Turnover at the ICJ Impact the Genocide Trial?

- On the Record | Which Israeli Politicians are Being Accused of Incitement of Genocide at the ICJ?

- Court Issues New Ruling Over Chabad World Headquarters

- The Short Leap from Anti-science to Antisemitism with Peter Hotez and Jennifer Bardi

- From the Newsletter | Is Context Everything?

- Ben-Gvir Boldly Puts Bibi—and Biden—in a Bind

- Israel Dispatch | The Hostage Dilemma: Is There Really No Price Bibi Will Pay?

- Ask the Rabbis | Does Jewish Wisdom Offer Help in Coping with Depression?

- What Three Words Describe Your Judaism?

- Spice Box | Bottoms Up

- The Conversation

- Red Sea Rebels: Yemen and the Houthis with Michael Knights and Nadine Epstein

- Wisdom Project | Lusia Milch, 92: “Doing Nothing Is Not Acceptable”

- ICJ Decision Puts Ball in Bibi’s Court: Israel Must Show It’s Complying with International Law

- The Soul of Israel: Lost in Translation with Daniel Gordis and Amy E. Schwartz

- New French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal is no Stranger to Prejudice

- Poem | Kaddish for the Living

- How A Set of Twins Survived the Holocaust Together with Michael Berenbaum and Marion Ein Lewin

- Interview | Laziza Dalil on Teaching Moroccan Jewish Heritage

- Memoir | International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the Danish Rescue

- Tu B’Shvat: A Birthday for the Trees

- Muslim and Arab Voices Against Bigotry

- The Importance of Storytelling in the Black and Jewish Communities with Eric K. Ward, Nadine Epstein, Adam Mansbach and Langston Collin Wilkins

- Fania Oz-Salzberger Reads ‘A Quick Guide To Zionism In Hard Times’

- Who Will Lead the Priestesses?

- Will Congress Pressure Israel?

- From 2016 | How The Black Lives Matter and Palestinian Movements Converged

- Duckworth: Life as a Unity

- Q&A | The Israel-Hamas War: Updates and Analysis (Part 3) with Aaron David Miller

- Shifting Identities after September 11th and October 7th with Dean Obeidallah and Max Brooks

- Interview: Pink Pancake’s Jewish Drag Journey

- The Courage of Eric K. Ward

- Tel Aviv Dispatch | A Beloved Bookstore in the Before and After

- From the Editor | Must We Harden Our Hearts?

- Visual Moment | A Cinematic Window on the Conflict

- Black-Jewish Relations: Coming Together to Fight Racism and Antisemitism with Rochelle L. Ford and Nadine Epstein

- Moment Debate | Should Students Be Disciplined for Chanting “From the River to the Sea”?

- Opinion | Serious Leadership Means Standing Together

- Book Review | She Came, She Sang, She Conquered

- Book Review | When an Adored Villain Gets His Day in Court

- Opinion | Right Now, The Political Is Personal

- Opinion | Yes, Context Matters

- Mood | In Israel, October Never Ended

- SNEAK PEEK: 2024 Jewish Political Voices Project

- Opinion | A Quick Guide to Zionism in Hard Times

- Jewish Word | Amalek, Then and Now

- Coming Together for an Inspiring Moment Program with Anne Applebaum, Dorit Beinisch, Esther Safran Foer, Lauren Holtzblatt, Dara Horn, Eric K. Ward, Robert Siegel and many others

- On Primaries, Caucuses and Hitler Comparisons

- From the Newsletter | A Wise Person Once Said…What Exactly?

- Interview | Dr. Zeina Barakat on Palestinian Views of the Holocaust and Reconciliation

- The Israel-Hamas War: Updates and Analysis (Part 3) with Aaron David Miller and Robert Siegel

- At Fraught Moment, Israel’s High Court Upholds Its Own Powers

- Opinion | Religious Absolutism: Isaac and Ishmael

- Ask the Rabbis | What is the Role of the Prophetic Voice in Today’s World?

- The Great Arab Revolt and Its Echoes Today

- Four Novels of 2023 That Are More Jewish Than You Thought

- Jewish Politics—A Year in Review

- From the Newsletter | Degrees of Evil—and Joy—in 2023

- Moment’s Top Stories of 2023

- Interview | Between Missile Strikes, Activist Mohammed Dajani is Still Dedicated To Peace

- An Inspirational Conversation with Holocaust Survivor Manfred Lindenbaum

- Ye’s New Album ‘Vultures’ Criticized for Antisemitic Lyrics and Art

- IDF Spotters: ‘The men ignored us, and we all paid dearly’

- From the Newsletter | When Psychiatry Made Being Gay OK

- How the “Woke” Movement is Undermining its own Goals and Unintentionally Pushing Society to the Right with Susan Neiman and Robert Siegel

- Memoir | Seeing Green in Southern Israel

- Video Essay | Volunteers Head South to Help Israeli Agriculture

- From 2005 | Ask the Rabbis: Should Jewish Children Sing Christmas Carols

- Women Speak Out: Confronting War, Rape, and the Rise in Hate: An Interfaith Conversation with Zainab Khan, Shirin Taber, Heidi Basch-Harod and Nadine Epstein

- Watching ‘Israelism’ from Wesleyan

- Stefanik Schools the Ivies

- ‘Deeply Rooted’—Pursuing Reproductive Justice Through Art

- Opinion | For Israel: A Blank Check or Tangled Strings?

- Top 10 Jewish Books of 2023

- From 1981 | Citizen Lear

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of December 4, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of November 20, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of November 6, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of October 16, 2023

- Wisdom Project | Manny Lindenbaum on the Joy of Making a Difference

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of September 25, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of September 11, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of August 28, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of August 14, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of June 19, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of June 5, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of May 22, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of April 10, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of March 27, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of March 13, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of February 27, 2023

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of February 13, 2023

- Wisdom Project | Gloria Levitas, 92 and counting!

- A Few Highlights from Moment’s 2023 Gala

- From the Newsletter | Stop Drawing Lines in the Sand

- Moment Gala 2023: Civil Rights Strategist Eric K. Ward

- Watch Moment’s 2023 Gala

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of January 16, 2023

- Book Review | Henry Kissinger on Successful Leadership

- A View from the Gulf States with Bahraini journalist Ahdeya Al Sayed and Nadine Epstein

- How Have 10/7 And The Israel-Hamas War Changed Your Priorities And Activism?

- Talk of the Table | The Ever Malleable Marzipan

- Keepers of the Diagnostic Keys

- Spice Box | Nobody Wants a Second Cut

- The Conversation

- Poem | Still Life with Nazi-Looted Art

- Joe Biden’s New Full-Time Job

- Poetry | Reheat, by David Israel Katz

- Opinion | Breaking the Silence on Hamas’s War Crimes Against Women

- Continuous Service Guarantee

- Tough Talk at Thanksgiving

- Book Review | Hollywood Gets the Mamet Treatment

- Book Review | Revisiting a 1920s Thrill Kill

- Visual Moment | John Singer Sargent: Fashioning Art

- Issue Blast | November/December 2023

- Opinion | What This Jew is Learning From This War

- Moment Debate | Do Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Initiatives Harm Jews?

- Opinion| Get Off Twitter Already

- Opinion | Poland’s Democratic Comeback

- A Sign of the Times

- Vivian Silver: 1949-2023

- Opinion | When Government Leaves a Void

- Opinion Interview with Dina Porat | Do Israelis Want Revenge?

- Interview | The Perilous State of Our World Order

- Essay | The Stolen Beam

- Moment’s 2023 Benefit & Awards Gala

- Jewish Word | The Twisted Path of the Word ‘Genocide’

- From the Newsletter | Anne Applebaum, Dorit Beinisch and More!

- How to Negotiate with Terrorists and Bring Hostages Home with Ory Slonim and Dan Raviv

- Photo Essay | The November 14 Pro-Israel Rally in DC

- From the Editor | A Dangerous Paradigm Shift—for Everyone

- The Spice of Life

- Unprecedented Interest in DC March for Israel

- An Inside Look at What’s Happening in the Palestinian Authority Today: A Wide-Ranging Conversation with Ghaith al-Omari and Nadine Epstein

- The Rise of Antisemitism since October 7th with Ira N. Forman and Sarah Breger

- From the Newsletter | GOP Debate & the Beer Hall Putsch Centennial

- Opinion | The Campus Conundrum

- From 1975 | Can Israel Win Another War?

- Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch, an Anti-Jewish Pogrom, and the U.S. State Department

- The World Order Under Threat: How Russia, Iran and China Benefit from the Israel-Hamas War with Ilan Berman and Nadine Epstein

- Laughter in a Time of Mourning with MODI

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of December 19, 2022

- Interview | Let’s Say Israel Can Destroy Hamas. Then What?

- The Anatomy of a Pogrom

- Keeping the Hostages Front and Center

- What Can We Do With Our Anguish? Stay United and Fight

- The Israel-Hamas War: Updates and Analysis (Part 2) with Aaron David Miller and Robert Siegel

- The GOP’s Pro-Israel Fest

- From the Newsletter | New House Speaker, Same George Santos

- Danger on Israel’s Northern Border: An Interview with Hanin Ghaddar About Hezbollah and the Failed State of Lebanon

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of November 21, 2022

- From the Newsletter | The Arsenal of Memory

- From 2006 | Marked For Life

- The Israel-Hamas War Through the Eyes of an Israeli Writer with Fania Oz Salzberger and Amy E. Schwartz

- Opinion | We Israelis Need Moral Clarity—Not Revenge

- How Theater Transforms the World with Mandy Patinkin, Kathryn Grody and Gail Merrifield Papp

- Dispatch | Tensions Rise for Palestinians in East Jerusalem

- Antisemitism Monitor | Week of November 14, 2022

- “Stop All the Killing—Then We’ll Talk!”

- Moment Magazine-Karma Foundation Short Fiction Contest

- Opinion | We Will Never Be the Same

- Son of Hamas Hostage: ‘This fight is about light and dark’

- Danger on Israel’s Northern Border: Hezbollah and the Failed State of Lebanon with Hanin Ghaddar and Nadine Epstein

- Opinion | The Arsenal of Memory

- European Leaders Largely Back Israel—For Now

- The Cost of Free Land: Jews and the Lakota with Rebecca Clarren and Sarah Breger

- U.S. Offers Mix of Advice and Warning in Full Support of Israel

- Interview | How Israel’s Allies Are Addressing the War On Campus

- From the Newsletter | Anything but Normal

- Misinformation About the War Abounds Online. Here’s What to Look For.

- Resident of Nir Oz Kibbutz, Whose Son Remains Missing, Recounts Attack

- Americans Rally, Rage and Grieve after Attack on Israel

- Gaza Timeline: 3300 BCE to the Present

- Q&A | Aaron David Miller: Hamas Incursion a ‘Fundamental Shift’ in Conflict

- Fiction // Berkeh’s Story

- Opinion | After Destroying Hamas, Israel Should Offer Control of Gaza to PA

- Opinion | Degrees of Evil in Israel’s Calamity

- Biden Fully Behind Israel as Horrors of Hamas Attack Emerge

- How Jewish Theater Combats Antisemitism with David Chack, Hayley Finn, Aaron Henne and Jenny Rachel Weiner

- The Israel Hamas-War: Updates and Analysis (Part 1) with Aaron David Miller and Robert Siegel

- The Israel-Hamas War: Updates and Analysis

- From the Newsletter | The Brilliant and Formidable Alice Shalvi

- Who’s Challenging George Santos?

- Playlist | Jewish Punk in Israel and North America

- George Santos, Seeking Re-Election, Still Claims He’s ‘Jew-ish’

- Ecological Judaism with Ellen Bernstein, Natan Margalit and Noah Phillips

- Why the Visa Waiver Is Such a Big Deal

- Dianne Feinstein (1933-2023): Trailblazer, Legislative Powerhouse, Jewish Woman

- The Yom Kippur War and How it Created the Modern Middle East with Uri Kaufman and Dan Raviv

- Wisdom Project | Harold Grinspoon Wants You to Discover Your Creative Side

- Jews & the Burden of Southern History

- Fiction // The Kiss

- Miami Is Changing—So Are Miami’s Jews

- Fiction // Two By Four

- Wax, Hide, and Gall: Jewish Ancestral Crafts are Making a Comeback in the U.S.

- Interview | Beyond Bagels & Lox

- Visual Moment | A Sephardi Silversmith’s Masterwork

- Talk of the Table | The Locusts Are Coming!

- What Is the U.N. Doing to Fight Antisemitism? A Wide-Open Conversation with U.N. Special Advisor Alice Wairimu Nderitu and Noah Phillips

- Musk, UN, Biden and Protests: What to Look for During Netanyahu’s U.S. Trip

- From the Newsletter | Shana Tova! Let’s See the Fruits!

- Shana Tova in the Mail: A Collector’s Vintage Jewish New Year Cards

- Spice Box | Substitute Dachshund for $1

- Poem | The Hidden

- The Conversation

- From the Editor | A Season of Self-Reflection

- Memoir | Crossing the Krimml Pass

- Fiction // Notes on Jewish Beauty (or: Tamara Herschel)

- Fiction // Raoul Wallenberg in Orbit

- Fiction // Remnants, Like Dust in Pocket Seams

- From 1986 | The Paavo Nurmi Marathon: Where are the Jews?

- Opinion | For Israel, Days of Judgment Are Looming

- Opinion | Three (Not So) Little Words

- Beshert | “B,” as in Beshert

- From Barbie to Artificial Intelligence and Everything in Between: A Wide-Open Conversation with Tiffany Shlain and Nadine Epstein

- Jewish Word | Not That Kind of Rabbi

- Book Review | The Maker and Breaker of Ideas

- Book Review | The Baggage You Can’t Leave Behind

- Book Review | The Voice Behind the ‘SWISH!’

- Opinion | When Not All U.S. Passports Are Created Equal

- Ask the Rabbis | When Have You Changed Your Mind About Something Important?

- Moment Debate | Would Israel Be Better Off Without U.S. Military Aid?

- From the Newsletter | Is Elon Musk Really Going to Sue the ADL?

- Opinion | How I Got Israel Wrong

- Fiction // Mark Gertler in 13 Sketches

- Fiction // Yiddish Land

- Daughter of History: From Holocaust Refugee to American Teenager with Susan Rubin Suleiman

- Playing the Israel Card in the First GOP Debate

- Fiction // Levi

- Fiction // Mirušenka Moja

- From the Newsletter | What Would Golda Think of Israel Today?

- Can Jewish Artists Transcend Germany’s Past?

- Jewish Film Review | A Requiem for Golda

- From the Newsletter | Kohenet’s Final Ordination of Hebrew Priestesses

- WATCH | New Holocaust Museum Opens—In a Video Game

- From 2007 | Lost in India

- Exploring Today’s World Through Poetry with Richard Michelson & Amy E. Schwartz

- In the Aftermath of Maui’s Wildfires, a Rabbi-Turned-Farmer Steps Up

- Boychik in Blue: An Interview With the NYPD’s Chief Jewish Chaplain

- Fiction // Three Dreams

- Fiction // How Beautiful Are Your Tents, O Jacob?

- From 2009 | Pilgrimage to Uman

- In ‘The Moss Maidens,’ Young Women Seduce Nazis to Kill Them

- Wisdom Project | Lucille Weener, 90

- Book Review | From Half a Line to Hebrew Heroine

- From the Newsletter | Is AI Good for Humanity?

- Oy, Oy, AI: What ChatGPT Can Tell Us About Jewish Jokes

- Could America Cut Aid to Israel? And Would It?

- The Actors and Writers Strike from a Jewish Perspective

- Fiction // The Goose Girl

- From the Newsletter | When the State Serves Death

- Federal Jury Hands Death Sentence to Tree of Life Synagogue Shooter

- Spice Box | Buy Our Big Wood

- Texas to Execute Jewish Man on World Day Against the Death Penalty

- Fiction // The Girl of the Comet

- The Conversation

- ‘Not Very Pleasant’

- From 2004 | Who Holds the Deed to the Holy Land?

- Comic | Learning to Dance with AI

- Q&A: Isabel Kershner on The Battle for Israel’s Soul

- The Battle for Israel’s Soul with Isabel Kershner and Sarah Breger

- Analysis | A Dark Day for Israeli Democracy

- After Abbas | Interview with Ghaith al Omari

- Talk of the Table | A Chat with ChefGPT

- Ask the Rabbis | What Impact Will Artificial Intelligence Have On People’s Spiritual Lives?

- As Israel Reaches a Boiling Point, Washington’s Concern Grows

- Sing to Survive: New Jewish Songbook Combats Climate Crisis

- Jewish Word | Beware the Fires of Moloch

- From the Archive | More Poetry of Linda Pastan

- Wisdom Project | Edith Everett, 94

- Explainer | Who Is Kidnapped Researcher Elizabeth Tsurkov?

- From the Newsletter | Remembering Poet Linda Pastan

- Roundtable | Robots Get Religion

- Partly Cloudy Reads for Your Beach Bag

- Book Review | The Truth Only Fiction Can Touch

- Q&A: The Poems in Progress of Linda Pastan, z”l

- Book Review | The Many Layers of Jewish Identity

- Visual Moment | Photographer Richard Avedon’s New Take on the Group Portrait

- Sanctuary and Humiliation: The Wartime Haven in Shanghai

- From 1994 | Argentina’s Jews After The Bomb: From Scapegoats to Pariahs

- Great Women Yiddish Writers (You Never Heard About) with Anita Norich and Lisa Newman

- Watch: Learning from Isaac Asimov

- Moment Wins 15 Rockower Awards at AJPA Ceremony

- Opinion | All My Children

- From the Editor | Learning from Isaac Asimov

- Opinion | Fear and Loathing in the Library

- Poem | The Mysteries

- Moment Debate | Is Changing Our Personal Behavior Key To Saving The Planet?

- Opinion | When Tyrants Overshoot

- Opinion | To Coin a Crime

- A Conversation about the Life and Legacy of Elie Wiesel with Joseph Berger and Nadine Epstein

- Beshert | Shedding Our Flak Jackets

- Beyond Bagels and Lox: Writing about Jewish Lives in the 21st Century with Allegra Goodman and Amy E. Schwartz—in celebration of the Moment-Karma Short Fiction Contest

- Fiction | Chelm, NJ

- Fiction | Night of Broken Glass

- Fiction | Arguing with Reinfeld

- Biden Speaks His Mind in Candid Interview

- From Chatbots to Cheesecake: 8 Brilliantly Jewish Uses of AI

- The End of Affirmative Action?

- My Friend Anne Frank with Dina Kraft and Laurel Leff

- Deep Dive | Whose Speech Is Free on Musk’s Twitter?

- Broadway Responds to Antisemitism with Tovah Feldshuh, Bruce Sussman, Alfred Uhry and Lynne Marie Rosenberg

- It’s the Settlements, Stupid

- Joshua Malina Is a Proud (((Jew)))

- Memoir | The One Whose Love Could Not Be Substituted

- Summer2023

- Announcing the Winners of our Short Fiction Contest

- Asian AND Jewish: An Insider & Outsider Perspective with Maryam Chishti, Rabbi Jacqueline Mates-Muchin and Michael Krasny

- Paula White Endorses Trump in Israel as Theme Park Temple Falls in Florida

- Wisdom Project | Agnes Biro Rothblatt, 90

- Visual Moment | Israeli Artist Sigalit Landau’s Immersion in the Dead Sea

- Montana Rep (And Rabbi) Confronts Christian Lawmakers after Invocation Cancellation

- Moment Wins Best Magazine Column at Dateline Awards in DC

- The Untold Story of Anne Frank & Bep Voskuijl with Joop van Wijk Voskuijl, Jeroen De Bruyn and Kati Marton

- Marching for Israel: Lessons Learned

- The Vice President, Simcha Rothman and a TikToker Walk into a Party…

- Antisemitism, World War II and FDR’s “Arsenal of Democracy” with Craig Nelson and Dan Raviv

- And the Bride Closed the Door by Ronit Matalon with Shulamit Reinharz

- Judaism Disrupted: A Spiritual Manifesto for the 21st Century with Michael Strassfeld and Amy E. Schwartz

- Sturm und Drag

- From 2001 | The Gay Orthodox Underground

- Is Ice Cream Good for the Jews?

- A New Plan to Fight Antisemitism, and the Politics Behind It

- Book Interview | Elizabeth Graver Tells the Family Story Behind ‘Kantika’

- The Key Judicial Reforms Tearing Israel Apart

- Memoir | Only Living Bodies Bleed

- Beshert | When the Love of Your Life Practically Falls through Your Ceiling

- If All the Seas Were Ink with Ilana Kurshan

- At JC3, Judaism Blossoms Among the Expats of San Miguel

- Ceasefire in Gaza, Mixed Messages in DC

- ReAwaken America Tour Fuses Trumpism and Christian Nationalism

- Wisdom Project | Eleanore Carsons, 104

- Seeking Revenge After the Holocaust with Dina Porat and Amy E. Schwartz

- From 1999 | After Arafat

- After Abbas: Palestinian Unification or Into the Lion’s Den?

- Jewish Film Review | Jerusalem Balagan

- After Abbas | Interview with Avi Melamed

- After Abbas: A Special Report

- After Abbas | An Interview With Menachem Klein

- After Abbas | An Interview With Itamar Marcus

- An Interview With Khalil Shikaki

- The Debate over Dianne Feinstein

- Speaking for the Silenced: From the Inquisition to the Holocaust with Richard Zimler and Sarah Breger

- He’s Running. Again.

- The Conversation

- Essay | The Women Who Shaped Israel

- Ask the Rabbis | What Does Israel Reaching 75 Mean in the Context of 3,000 Years of Jewish History?

- The Growing Threat of Christian Nationalism with Guthrie Graves-Fitzsimmons, Katherine Stewart, Eric K. Ward and Robert Siegel

- Analysis | Scenes from a Memorial Day Like No Other

- 10 Innovations of Israeli Technology

- Is Yom Ha’atzmaut’s Date All but Moot?

- From the Editor | Finding a Balance Between Israel and the Diaspora

- Talk of the Table | A Feast to Celebrate 75 Years

- Spice Box | There Lived a Country Boy Named Johnnie B. Goy

- The State of the Jewish State

- An Interview with Gidon Bromberg | When Water = National Security

- Is Holocaust Education Feeding Antisemitism?

- All the Rivers with Dorit Rabinyan

- From 1996 | Shifting Borders

- Poem | Fruit of the Land

- Moment Debate | Has the Word Zionism Outlived its Usefulness?

- Jewish Word | Israel: What’s in a Name?

- Taking a Break from Battling Trump, DeSantis Heads to Israel

- Meir Shalev’s Distinctive Israeli Voice

- The Mensch in the Bench

- Recipe | JERUSALEM KUGEL

- Antisemitism Monitor Country Profile: Romania

- Wisdom Project | Erika Hassan, 92

- Opinion | Beyond ‘Never Again’

- Opinion | Israel, We’ve Got to Talk

- From Nazi Granddaughter to Holocaust Scholar: Researching the Vatican’s Holocaust-Era Archives with Suzanne Brown-Fleming and Shana Penn

- Drama in Israel Makes for New Partnerships in America

- Book Review | America, Jews and Israel— It’s Complicated

- Literary Moment | Traveling the Land, Book in Hand

- Book Review | A Writer Whose Stories Bite Deep

- Opinion Interview with Dahlia Lithwick | Do You Really Want That Abortion?

- On the Ground from Israel with Eetta Prince Gibson and Sarah Breger

- Israel Update: Protests Pump the Brakes—for Now

- Will the Third Temple Survive its 75th Year?

- Why We Need to Help the Uyghur People in China NOW with Elfidar Iltebir, Elisha Wiesel, and Josh Rogin

- Suddenly, a Knock on the Door: Stories with Etgar Keret

- Alarming Rise of Antisemitic Behavior in Schools

- Is the Anti-Establishment “Woo-to-Q Pipeline” Antisemitic?

- Jarring, but Funny: History of the World Part II is a Fitting Sequel

- The State of Antisemitism in America with Ted Deutch and Robert Siegel

- Are Democrats Becoming Anti-Israel?

- No, Jews Aren’t Being Erased—We’re Just Sharing the Pie

- How to Impress Others with Your TikTok Knowledge

- Bulgarian Nazis: Now and Then

- Bookstagram Backlash for The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

- Daniel Pearl Investigative Journalism Initiative Goes Deep

- Golda Meir and Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Pioneers of Women in Power with Pnina Lahav and Nadine Epstein

- From 1988 | An Interview with UN Ambassador Benjamin Netanyahu

- Rage Against the Rube Goldberg Machine

- The Changing Relationship Between American Jews and Israel with Eric Alterman and Dan Raviv

- Memoir | Digging Deeper

- Mr. Smotrich Goes to Washington

- Teshuvah for Jimmy Carter

- Explainer: How Bibi’s New All-Right Coalition is Responding to West Bank Violence

- From 1984 | My Interview with Jimmy Carter

- From 1984 | My Hour with Jimmy Carter

- Ladino in Turkey: Rescuing an Endangered Language

- Telling Jewish Stories Through Music with Hershey Felder and Joe Alterman

- Purim: The Jewish Halloween

- Memoir | Grief and the Lemon Tree

- Opinion | Is Our Fear of Antisemitism Poisoning Our Discussion of Israel?

- A few lovingly chosen poems by Yehuda Amichai with Robert Alter

- The Real Jews of Hogan’s Heroes with Walter J. Podrazik and Harry Castleman

- With a Push and a Nudge, Biden Shows Bibi the Exit Ramp

- How Much Do We Really Know About Hebrew Israelites?

- Let the Comedians Say What They Want! with Judy Gold and Joe Alterman

- Wisdom Project | Ann Jaffe, 91

- Opinion | Friends of Israel, Be Very Afraid

- The “Normalization” of Antisemitism with Gavriel D. Rosenfeld and Amy E. Schwartz

- Analysis | In the Streets for Democracy

- Doug Emhoff Is Meeting His Moment

- Update: Israeli Democracy Under Threat

- Meret Oppenheim: My Exhibition

- Who Are the Hebrew Israelites? with Andre E. Brooks-Key, Eric K. Ward and Nadine Epstein

- An Interview with Ambassador Deborah Lipstadt

- From the Newsletter | Honor Thy Children—and Elders Too

- Lessons from Ilhan Omar’s Removal from the Foreign Affairs Committee

- Jewish Film Review | The Offering

- Back in Time to 1909: The Black Jewish Relationship and the founding of the NAACP with Lillie J. Edwards and Nadine Epstein

- Meet the Five New Jewish House Members

- From the Newsletter | Holocaust Remembrance Day: Recall, Engage and Preserve. But Reimagine?

- Who Will Replace the Last Eyewitnesses to the Holocaust?

- Why Were 99 Percent of Holocaust Murderers Never Prosecuted?

- Kyiv Diary 1/26/23: Powerful Gifts from the United States

- Escaping Auschwitz with Jonathan Freedland and Dan Raviv

- Spice Box | When J-Date’s Not Good Enough

- Ten Jewish TikTokers

- Poem | Augury

- Interview | Max Weinberg, King of the Beat

- Abortion Rights: Where Jewish Ultra-Orthodox and Christian Conservatives Meet

- The Conversation

- An Interview with Ukrainian Ambassador Oksana Markarova

- Will Netanyahu Follow the High Court’s Order on Deri?

- Visual Moment | Tales of Rifles and Resistance

- Book Review | The Journey of a Baghdadi Dynasty

- Talk of the Table | Waste with Taste: Peels, Stems, Tops and More

- The Educational Legacy of Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington with Dorothy Canter, Marian and Valerie Coleman, Stephanie Deutsch, Andrew Feiler and Aviva Kempner

- Book Review | Degrade and Destroy

- The Meaning of ‘Semicha’

- Governor Josh Shapiro: Not Your Grandfather’s Jewish Politician

- From Zero to Hate in Just a Tik and a Tok

- Setting Santos’s Congressional District Free

- Book Review | A Girl Who’s Born to Climb

- Moment Debate | Will Changing the Law of Return Harm Israel-Diaspora Relations?

- Opinion | Does the Law of Return Need Changing?

- Opinion | The Neurosis of ‘Jewish Power’

- Opinion | A Perilous Path for Republicans

- From the Editor | First Encounters of a Hateful Kind

- Ask the Rabbis | What Jewish Wisdom Would You Offer Today’s Billionaires?

- Opinion | Who’s Afraid of Ben-Gvir and Smotrich?

- The Musical Legacy of Leonard Cohen with David Broza and Amy E. Schwartz

- Was ‘Mensch Mayor’ Steve Schewel Good for Durham’s Jews?

- Wisdom Project | Donald J. Stone, 93

- The Good, the Bad and the Algorithm

- America Responds to Bibi

- From the Newsletter | Sniffing Out the Messiah in 2023

- Remembering My Colleague, Barbara Walters

- 12 Books That Made Us Think in 2022

- Moment Memoir | Shame, Names and the Mengele Tractor Factory

- Netanyahu Rolls Out His New Government; Jewish Americans React

- Kyiv Diary 12/26/2022: Light in the Winter Darkness

- Wisdom Project | Rabbi Arthur Ocean Waskow, 89

- Moment’s Top 10 Most-Read Stories of 2022

- A Musical Journey in Search of Iraqi-Jewish Roots with Yoni Avi Battat and Joe Alterman

- After Corbyn’s Exit, Is the Labour Party Safe for UK’s Jews?

- Crime or Crisis: Disentangling Mental Illness and Antisemitic Violence

- The Seifter Menorah: Fingerprints From a Vanished World

- From the Newsletter | Let’s Make Hanukkah a Time to Remember Great Women

- From The Rabbit Hole: Yanuka, the Youtube Antichrist

- Who Edited Hanukkah Out of the Bible?

- Hanukkah: The Festival of Cheese with Vered Guttman

- Can the Government Save America from Antisemitism?

- The Power of Friendship: Dinners with RBG and others with Nina Totenberg and Nadine Epstein

- A Virulent Antisemitism: An Interview with Dr. Peter Hotez

- Rabbis in States with Abortion Restrictions Find Hope in Interfaith Work

- Closing the Circle with an Old Comrade

- A Wide Open Conversation with Ken Burns and Michael Krasny

- Trump’s Table: Heaps of Antisemitism with a Side of Possible Indictments

- Jewish and LGBTQ Communities Stand Together Against Club Q Shooting

- ‘Ukraine Never Asked for Blank Checks,’ says Ambassador Oksana Markarova

- Deborah Lipstadt‘s Mission to Fight Antisemitism

- From 2009 | The Pomegranate: A Rich and Holy History

- From the Archives | Arthur Waskow’s Thanksgiving Story

- Moment 2022 Gala Clips

- What Are Sayanim?

- A Robert Siegel Interview with Ukrainian Ambassador Oksana Markarova

- An Amy E. Schwartz Interview with Emily Bazelon

- A Robert Siegel Interview with Ambassador Deborah Lipstadt

- A Nadine Epstein Interview with Max Weinberg

- Chappelle Stirs the Pot As Fallout from Kanye’s Antisemitism Boils Over

- After the Midterms: Now What? And What’s the State of Our Democracy? with Jennifer Rubin and Robert Siegel

- Role Models Part II

- Talk of the Table | Falafel: The Crunch that Binds or Ball of Confusion?

- Jewish Word | ‘Almah’ Grows Up

- Breaching the Wall

- The Conversation

- First Jewish Miss Wyoming Heading to National Stage

- Fiction | Calculated Moves

- Poem | ALIYAH

- Victories and Tensions in U.S. and Israeli Elections

- Spice Box | The Merger We Should Have Seen Coming.

- Book Review | Whose Biblical Law Is This, Anyway?

- Wisdom Project | Martin Katz, 95

- From the Newsletter | How We’re Responding to Changes at Twitter

- How We’re Responding to Twitter

- Election Day 2022: Jewish Jokes Edition with Bill Novak

- Bibi’s Back: Quick Reactions from Four Moment Contributors

- Moment Debate | In Embracing Hungary’s Orbán, Are American Conservatives Romancing an Antisemite?

- Ask the Rabbis | How Would You Counsel a Parent and Child Who Are Estranged?

- Book Review | Very, Very Dirty Money

- Book Review | The Maus That Roared

- Opinion Interview | Who Gets a Religious Exemption?

- Book Review | A Jewish Kid Who Loved Yeats

- Visual Moment | The World Inside Carl Moll’s ‘White Interior’

- Jewish Film Review | When Austrian Justice Fails

- Beshert | From Cuppa to Chuppah

- From the Editor | The Eighth Night: A Time to Remember Great Women

- Opinion | We Are What We Give

- Opinion | The Case Of The Praying Coach

- Opinion | Are Haredim Failing Their Children?

- Kyiv Diary 11/4/22: Even Without Electricity, Kyiv Has Power

- From the Newsletter | The Jewish Vote in the Midterms

- Alabama Israelite: New York Transplant Seeks Seat in Alabama Legislature

- Is There Such a Thing as a Bad Jew? The Confluence of American Jewish Politics and Identity with Emily Tamkin and Dan Raviv

- Tomorrow’s Election in Israel : A Guide for the Perplexed

- The Great Jewish Short Stories of Singer, Malamud, Ozick & Roth with Dr. Michael Krasny

- Who Should See the New Tree of Life Documentary

- Analysis | How the Israeli Right Hopes to Reshape the Legal System

- Shanda! Shameful Family Secrets with Letty Cottin Pogrebin and Abigail Pogrebin

- Stanford’s Apology and the Importance of Archives

- What You Need to Know About Kanye West’s Recent Comments About Jewish People

- Opinion | What Was Different about the Latest Riots in Jerusalem

- Trump Is at It Again

- Chickens and Sheep and Goats, Oy Vey! The New Jewish Farmer with Wendy Rhein, Adrienne Krone and Noah Phillips

- Book Review | Biography of a Baron

- Wisdom Project | Eileen Lavine

- Moment Memoir | Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die?

- Kyiv Diary 10/10/22: The Missile Blast In My Neighborhood

- From 2006 | Edward R. Murrow: As Good as His Myth

- The Little-Known Story of Jewish Refugee Professors at Historically Black Colleges & Universities with Lillie J. Edwards and Nadine Epstein

- This Moment in Art: Draping the Ambassador’s House, Samaritans and More

- Does the Government of Hungary Really Have a “Zero Tolerance” Policy When it Comes to Antisemitism? with Ira Forman, Kati Marton and Amy E. Schwartz

- Who Are Your Role Models?

- Creating Streetscape Art: An Interview with Simonida Perica Uth

- Spice Box | “What Am I,” asks Hamm, “Chopped liver?”

- On Poetry | Nelly Sachs and the Poetry of Flight

- The Conversation

- Opinion | A Brief Break from ‘To Bibi or Not to Bibi’

- Biden Does Rosh Hashanah

- Thoughts at the End of a 7-Year Shmita Cycle

- Midterms ’22: What Our Jewish Voters Are Thinking

- From Undocumented Child to Successful American Jewish Lawyer and Writer with Qian Julie Wang and Sarah Breger

- Book Review | A Family of Ambitious Aristocrats

- Book Review | Secrets of a Musical Family

- Visual Moment | The Subversive Art of Philip Guston

- Book Review | Studying Talmud with Beruriah

- Talk of the Table | The Feast Before the Fast

- Where’s My Blockbuster King David TV Show?

- Opinion | The GOP’s Christian Supremacy Problem

- Ask the Rabbis | Can Jews Married to Non-Jews be Considered Spiritual Leaders in the Jewish Community?

- From the Editor | ‘Make for Yourself a Rabbi’

- Opinion | Why is Israel Deadlocked?

- Moment Debate | Are There Dangers in the Increase of Israel-Related Money in American Electoral Politics?

- Foreign Affairs | Israel’s Complicated Dance with Putin

- Opinion | Who’s Crazy Now?

- The Road to Gender Equity with Ting Ting Cheng and Nadine Epstein

- Everything Is as You Thought It Would Be in Latest Jewish Voter Poll

- Yeshivas in the News

- Moment Nominated for ‘Religion Story of the Year’ and More

- Moment’s 2022 Benefit & Awards Gala

- Jewish Film Review | The Anguish of Losing Faith

- Book Review | Reviving Selihot, Judaism’s Midnight Prayer Service

- The U.S. Senate: America’s First and Last Lines of Defense with Ira Shapiro and Rabbi Eric Yoffie

- Deep Dive | More Jews Murdered in France

- Wisdom Project | Ted Comet

- Camel Caravans, Kasbahs and Berber Jews

- Kyiv Diary 9/12/22: Soldiers Drink for Free

- Why Antisemitism Flourishes in Election Season

- The Politics of Being Gay with Congressman Barney Frank, Eric Orner and Ann F. Lewis

- From the Newsletter | Martha’s Vineyard Jewish History Presented at Island’s Museum

- Sponsorships for Moment’s 2022 Benefit & Awards Gala

- Moment’s Gala 2022 Honorees

- Montana Jewish Project Succeeds in Buying Back Historic Helena Synagogue

- Kyiv Diary 8/31/22: Hustling in Krakow

- Zionophobia: A Wide Open Conversation with Judea Pearl

- My Dinner Party for Women’s Equality Day 2022

- Can Jewish Drag Help Combat Conversion Therapy?

- From the Newsletter | Frozen Russian Tanks and Rockets’ Red Glare

- Kyiv Diary 8/24/22: Independence Day

- Fiction | Homecomings

- A New Debate Over an Old Deal

- From the Newsletter | When Courageous Writing Gets You Hurt—Or Worse

- Euphoria’s Israeli Predecessor Shows that Teen Trauma Transcends Culture

- The Best Jewish Podcasts Released This Year

- Kyiv Diary: 8/16/22: The Legend of a Gray Haired Warrior

- Opinion | Rushdie is a Champion of Religious Freedom, Too

- Uganda’s Abayudaya Jews Dream of Aliyah

- The Wisdom Project | Aribert Munzner

- Moment Memoir | My Mother’s ‘Knippel’

- From the Newsletter | Can Hebrew Be Gender-Neutral?

- Let’s Get “Nosh-talgic” with Rachel Packer

- Book Review | Israel’s Star Turn

- A Defining Moment for Yair Lapid

- Vatican Archives Opened; Letters From Jews Revealed

- From the Newsletter | It’s deep midsummer. What are you reading?

- Sex, Love and Judaism Intertwine in ‘Love Me Kosher’ Exhibit

- Every Child is Our Child: Foster Care and Adoption with Rabbi Susan Silverman, Rob Scheer and Rita Soronen

- Kyiv Diary 8/2/22: A Scramble to Get Reborn at the Government Registry

- Deep Dive | The Difference Between Hating Jews and Antisemitism

- From the Newsletter | Exploring Jewish Community in Far Flung Places

- Why Was Season Four of Stranger Things Filmed in a Nazi Prison?

- Kyiv Diary 7/26/22: Mila’s Impossible Decisions

- South Africa: Triumphs and Troubles Since the End of Apartheid with Eve Fairbanks, Steve Friedman and Glenn Frankel

- Your Pro-Israel Dollars at Work

- Special Edition | The Making of a Jewish Word

- Everything is Material: The Influence of Love, Loss and Humor in Fiction and Memoir with Susan Coll, Delia Ephron and Amy E. Schwartz—in celebration of the Moment-Karma Fiction Contest

- Amid Antisemitism, Jewish Montanans Seek to Buy Back Historic Synagogue

- From 1997 | Finding My Father in Sephardic Time

- Spice Box | So, what are you waiting for, journal already!

- The Conversation

- Poem | A Visitor in Herzliya

- Kyiv Diary 7/15/22: Generosity From an Unexpected Twin

- State Department Condemns Russian War Propaganda as ‘Antisemitic’

- Beshert | The Crooner in the Station

- The Wisdom Project | Joan Scheuer

- A New Generation of Jewish Farmers Returns to the Land

- Talk of the Table | Cooking with Cannabis

- Visual Moment | A Window in Time: Europe, 1934

- Biden’s Upcoming Middle East Trip

- A Wide-Open Conversation about Antisemitism with Jonathan Greenblatt and Robert Siegel

- Simone Veil: The Holocaust Survivor Who Achieved Reproductive Rights in France

- Can Malmö Solve Its Antisemitism Problem?

- Summer Novels to Feast On

- Book Review | A Madcap Holocaust Holiday

- New Jewish Kidlit: Beyond the Holocaust and Holidays

- Book Review | The Temple of Whitefish and Lox

- Moment Debate | Are We Losing Our Democracy?

- Film Review: Talking Dirty With Golden Voices

- Opinion | Inside a Hasidic Schism

- Ask the Rabbis | Does Jewish Law Offer Guidance on How to Fight a War?

- From the Editor | Learning to Honor Words

- From 2009 | Ask the Rabbis | When Does Life Begin?

- Kyiv Diary 6/24/22: A Masorti Shavuot in Kyiv

- Bulli, In Loving Memory

- Victimhood in the Land of the Perpetrators

- Opinion | Not Your Grandfather’s Saudi Arabia

- Opinion | Plundered Palestinian Pastures

- Opinion | The Jewish Obligation to Ukraine

- Moment Memoir | Certify Me Normal

- Book Review | The Evolution of Tyranny

- The Wisdom Project | Dieter Gruen

- What Would God Say? A Comedy Date with David Javerbaum and Michael Krasny

- Israel’s Dissolving Government: An Explainer

- The Politics of Being Gay with Congressman Barney Frank, Eric Orner and Ann F. Lewis

- From the Newsletter | Gun Rights and Judaism

- From the Newsletter | Remembering A.B. Yehoshua

- How Social Media has Spread and Normalized Conspiracy Theories with Ambassador Karen Kornbluh, Sarah Posner and Jessica Reaves

- Witness to a Massacre: The Kamianets-Podilskyi Experiment

- The Black Jewish Relationship: Triumphs and Tensions with Eric K. Ward, Nadine Epstein and Clarence Page

- Costs of Cheap Oil: Biden’s Balancing Act

- Kyiv Diary 6/6/22: Families Reuniting, but at What Cost?

- Antisemitism Project | What Antisemitic Conspiracy Theorists Believe About Vaccines

- What Antisemitic Conspiracy Theorists Believe About Vaccines

- Kyiv Diary 6/1/22: Small Businesses Struggle to Recover

- Jewish Geography—Six Feet Under

- Wrestling With Moon Knight’s Judaism

- From the Newsletter | George Soros is a Holocaust Survivor, Not a Nazi

- Kyiv Diary 5/26/22: The City Wakes Up From a Nightmare

- Pot-Peddling Pensioners

- Book Review | The Netanyahus Takes Off

- Kyiv Diary 5/25/22: Supporting a Family During Wartime

- George Soros Is a Holocaust Survivor, not a Nazi with Nadine Epstein, Leon Botstein and Humphrey Tonkin

- Bernie Sanders’ War on AIPAC

- Beshert | Un-chickening Out

- Antisemitism Project | George Soros Is a Holocaust Survivor—Not a Nazi

- The Future of Berlin’s Jewish Museum

- Kyiv Diary 5/20/22: How a Ukrainian Jewish Business Owner Adjusted to Wartime

- From the Newsletter | The Exploitation of a Palestinian Journalist’s Death

- Kyiv Diary 5/19/22: In Times of War, Goodness Reawakens

- Opinion | The Exploitation of a Palestinian Journalist’s Death

- The indomitable Shari Lewis and Lamb Chop with Mallory Lewis, Nat Segaloff and Sarah Breger

- Kyiv Diary 5/16/22: Inside the Efforts to Help Ukraine’s Animals

- Jan Karski: Witness to the Holocaust with David Strathairn, Derek Goldman and Amy E. Schwartz

- The Intersection of Music and Prayer with David Broza and Amy E. Schwartz

- From the Newsletter | How Is Judaism Different After Half a Century of Female Clergy?

- From 2004 | Rhythm & Blues, Blacks & Jews

- Kyiv Diary 5/11/22: The Ukrainian Spirit Will Prevail

- Kyiv Diary 5/9/22: Ukrainian Families Torn Apart

- Busy Times in Jewish American Politics

- Lilacs and the Pit: Family Holocaust Recollections

- Antisemitism Project | What’s Changed Since the Poway Synagogue Shooting?

- The Story of Art Rupe and Specialty Records with Nadine Epstein and Billy Vera

- ‘H*tler’s Tasters’ Follows the Young Women Who Tested Hitler’s Food for Poison

- AIPAC Donations Rattle North Carolina Congressional Race

- Kyiv Diary 5/3/22: It’s Finally Spring, and Kyiv Is Rejuvenated

- The Thrilling World of Brad Meltzer

- New Children’s Books Chronicle the Lives of Prominent American Jews

- This Moment in Art: Murals in Odessa, The Art of Tobi Kahn and More

- Lesya Verba Reflects on Her Odessa Murals

- Trevor Noah Is an Outsider’s Outsider

- From the Newsletter | What Is the One Thing Students Should Leave College Knowing?

- Kyiv Diary 4/28/22: Ukrainians Waited in Line for Hours to Buy a Commemorative Wartime Stamp

- B’nai Mitzah Pairing Programs Honor Children Who Died in the Holocaust

- What’s Changed Since the Poway Synagogue Shooting?

- Letters from the Lingerie Drawer: A Daughter’s Journey with Eleanor Reissa and Yehuda Hyman

- Is the Iranian Revolutionary Guard a Terrorist Group?

- Beshert | Because I Wasn’t the Jazz Age

- Artist Tobi Kahn’s Works Explore Memory, Spirituality and Healing

- From the Newsletter | Germany’s Time of the Wolves

- Kyiv Diary 4/21/22: The Animals of Ukraine Are Also Suffering

- A Gothic Rendering of a Hero of Judaism

- Blacks, Jews, Jazz & Blues with Loren Schoenberg, Eric K. Ward and Nadine Epstein

- Kyiv Diary 4/19/22: A Wartime Passover Seder

- Kyiv Diary 4/18/22: Boris Johnson and Volodymyr Zelensky Stroll Past My Balcony

- Kyiv Diary 4/15/22: Passover, the Holiday of Freedom, Is More Relevant Than Ever

- What Is the One Thing Students Should Leave College Knowing?

- From the Newsletter | Have We All ‘Hardened Our Hearts’ à La Pharaoh in Egypt?

- The Jews Who Saved Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello

- The Violent History—and Remarkable Transformation—of Jewish Life in Ukraine

- Kyiv Diary 4/13/22: My Conversation With a Kyiv Rabbi

- Tzedek Chicago Is America’s First Anti-Zionist Synagogue

- Moment Debate | Should the Supreme Court Outlaw Affirmative Action?

- Visual Moment | The Synagogue, a Symbol of Endurance

- The Conversation

- Poem | Ketubah

- Spice Box | Militant Handyman

- How a Collection of Japanese Netsuke Sheds Light on a Jewish Family’s Tumultuous History

- Biden Tried to Go Easy on Bennett. It Wasn’t Enough

- Kyiv Diary 4/10/22: Across Ukraine, Russian Soldiers Commit Atrocities

- Kyiv Diary 4/8/22: Waiting to Meet the Rabbi

- Young Ukrainian Artists Respond to the Invasion

- From the Newsletter | How Shofars Became a Favorite of Christian Nationalists

- Beshert | Two Open Chairs

- Kyiv Diary 4/6/22: My Trip to a Kyiv Synagogue

- Why You Should Know Your DNA: Genetics, Testing and Disease Prevention with Paul Root Wolpe, Ali Rogin and Emily Goldberg

- Kyiv Diary 4/4/2022: ‘More Lobsters Than People in the Grocery Store’

- Book Review | Germany’s Time of the Wolves

- Talk of the Table | Adventures with Gefilte Fish

- Moment Brand Studio: Liza Wiemer Fights Antisemitism with “The Assignment”

- Jewish Word | Why We Say ‘Next Year in Jerusalem’

- Book Review | A Seder Reimagined By A Feminist Poet

- Book Review | Amos Oz Looks Back at Literature

- Fiction | Why Is There a Buddhist at this Seder?

- Kyiv Diary 4/1/2022: ‘Ukrainian Fashion Designers Support the War Effort’

- Beshert | I Was Done Writing Books. I Thought.

- Kyiv Diary 3/30/2022: ‘A Pretense of Normal Life’

- Susannah Heschel: The Rabbi’s Daughter

- The Jews of Iran: Antisemitism and the Great Exodus with Roya Hakakian and Sarah Breger

- In Israel, Jewish and Non-Jewish Ukrainian Refugees Face Separate Policies

- Kyiv Diary 3/28/2022: ‘We Fled Our Homes Not Knowing if We Would Ever Return’

- From the Editor | A Passover Call For Empathy

- Ask the Rabbis | How Is Judaism Different After Half a Century of Female Clergy?

- A New Power Structure in the Middle East

- Robert S. Greenberger

- Opinion | How Many Ukrainians Can Israel Absorb?

- Opinion | Look Who’s Blowing Shofars

- Opinion Interview | ‘We Have to Stop Orbán’

- Kyiv Diary 3/25/2022: ‘People Just Want To Survive. So, They Adapt to War’

- Opinion | An Israeli PM Steps Up To Diplomacy

- The Hollywood Blacklist and Its Jewish Legacy with Glenn Frankel and Margaret Talbot

- From the Newsletter | Diaries From Kyiv

- Bridgerton, Gossip and Marriage: What Does It Mean to Know Your Partner?

- Kyiv Diary 3/21/2022: ‘Love Is in the Air’

- Our Ahistorical Antisemitism

- Kyiv Diary 3/20/22: ‘Heartbroken Adults Are Forced To Leave the Elderly Behind’

- Black and Jewish views on Critical Race Theory with Janet Dewart Bell, Mia Brett, Eric K. Ward and Nadine Epstein

- Kyiv Diary 3/17/2022: ‘The Situation With Israel Bothers Ukrainians a Lot’

- Esther Before Ahasuerus by Artemesia Gentileschi

- From the Newsletter | How We Learn About the Holocaust

- Kyiv Diary 3/16/22: ‘This Night Four Buildings Were Bombed’

- Russian Aggression through the eyes of Eastern Europe with Konstanty Gebert and Amy E. Schwartz

- “So, Are Jews a Race?” Lessons from Purim and Beyond

- Memories and Stories of RBG on What Would Have Been her 89th Birthday with Nina Totenberg and Nadine Epstein

- Kyiv Diary: ‘Today Is a Good Day. We Have Netflix and Eggs’

- How (Almost) Everyone Is Supporting Ukraine

- Russia, Vladimir Putin and Ukraine: The Struggle Between Authoritarianism and Democracy with Natan Sharansky and Robert Siegel

- From the Newsletter | The Russia-Ukraine War, Through the Lens of Vietnam

- Why Women Need to Pray at the Western Wall with Anat Hoffman, Susan Silverman & Deborah Katchko-Gray

- What Is Putin Thinking?

- Recipe | GRANDMA’S BRISKET

- Kavod, Koved: In Search of Honor

- From the Newsletter | Whatever Happens Next, Putin’s Invasion Has Already Changed the World

- God, Sex and Politics in the Lyrics of Leonard Cohen with writers Erica Jong, Marcia Pally and Letty Cottin Pogrebin

- Russia and Ukraine, Explained

- The Resilience of Ukraine and Its Jews

- Living Jewish Literature With Faye Moskowitz

- Beshert | Erev Christmas Day

- From the Newsletter | Beshert: Stories of Connection in a Universe of Love

- Russia and Ukraine Explained with Ambassador Ivo H. Daalder and Robert Siegel

- Recipe | Natif

- How to Stay Safe in America During a Time of Increased Antisemitism with David Delew, Eva Fogelman Richard Priem, in conversation with Ira Forman

- From the Archives | The Afterlife is not an Afterthought

- The ‘Maus’ Trap: Famous Banned Books by Jewish Authors

- The Villainous Mrs. Maisel

- From the Newsletter | The Ripples Before the Storm

- Introducing ‘This Moment in Art’

- For the Love of Chocolate with author Michael Leventhal in conversation with Sarah Breger

- Crying Gevald on Capitol Hill

- Caribbean Kibbutz: How Racism Saved Hundreds of Jewish Refugees

- From the Newsletter | The Bnei Brak Bachur who became the Tinder Swindler

- Beshert: Stories of Connection in a Universe of Love

- The Conversation

- Rediscovering Majorca’s Jewish Past

- It’s Time to Take Antisemitism Seriously, Says Colleyville Synagogue Cofounder

- The Holocaust Through the Lens of Black-Jewish Relations with Eric K. Ward and Nadine Epstein

- Poem | “The Last Jew in Vinnitsa”

- Beshert | A Slow Start To Lasting Love

- From the Newsletter | A Jewish State, but What Kind?

- Book Review | Half a Century Ago, a Hostage Rescue That Gripped the World

- H Headings

- Trayon White Is Running for DC Mayor. Has the City Forgiven His Antisemitic Comments?

- The Remarkable Odyssey of Angela Merkel with journalist Kati Marton in conversation with Amy E. Schwartz

- Explainer: Congress’s New Gentile-Led Torah Caucus

- Book Review | The Ripples Before the Storm

- Book Review | The Palpable Joy of Journalism

- Book Interview | Anita Diamant and the Pursuit of Menstrual Justice

- Ask the Rabbis | Is Political Compromise a Jewish Virtue?

- Spice box | What Sort of Mushrooms, Exactly?

- Winners and Losers in the Boycott Wars

- Book Review | A Poet’s Appetite for Grief and Desire

- Staff Picks: ‘The Velvet Underground,’ ‘The Nazi’s Granddaughter’ and Tammy Faye

- From the Newsletter | The State of Holocaust Education in America

- After Seeing My Synagogue Attacked, How Can I Reconcile Security With Openness?

- Moment Debate | Would a Ban on Abortion Curtail Jews’ Religious Freedom?

- Visual Moment | Man Ray in Paris

- Could Nida Allam Become the Fifth Member of ‘the Squad’?

- Henry Kissinger and the Art of Middle East Diplomacy with Martin Indyk and Dan Raviv

- Opinion | Dinners and Dialogues Are Not Enough

- The State of Holocaust Education in America

- From the Editor | Elie Wiesel and Two Girls He Never Met

- Opinion | Blinded by a Black Hat

- Opinion | A Jewish State, but What Kind?

- Opinion Interview | Are Pro-Trump Jews Moving On?

- Beshert | Encounter in Eilat

- Talk of the Table | The Satisfying Sweetness of Dates

- Jewish Word | Shmita: A Sabbath for the Land—and Ourselves