by Andrea Greenbaum

In 1996, I spent a year in smoky comedy clubs in Tampa, Florida to document the rhetorical style of standup comedians. I paid close attention to their narratives, their body language, and then, after their sets, interviewed them about their craft—how they integrated writing and speaking in a public space. I discovered that women standup comedians used different strategies to win over their audiences, because humor has always situated itself in the realm of the masculine, and women must overcome the social taboo of speaking with authority in a public forum. My research, published in American Studies, “Women’s Comic Voices: The Art and Craft of Female Humor,” concluded that there are two themes that play throughout women’s standup performances:

In 1996, I spent a year in smoky comedy clubs in Tampa, Florida to document the rhetorical style of standup comedians. I paid close attention to their narratives, their body language, and then, after their sets, interviewed them about their craft—how they integrated writing and speaking in a public space. I discovered that women standup comedians used different strategies to win over their audiences, because humor has always situated itself in the realm of the masculine, and women must overcome the social taboo of speaking with authority in a public forum. My research, published in American Studies, “Women’s Comic Voices: The Art and Craft of Female Humor,” concluded that there are two themes that play throughout women’s standup performances:

1) They use the feminine body as a site of discourse and

2) they establish uniquely female narratives.

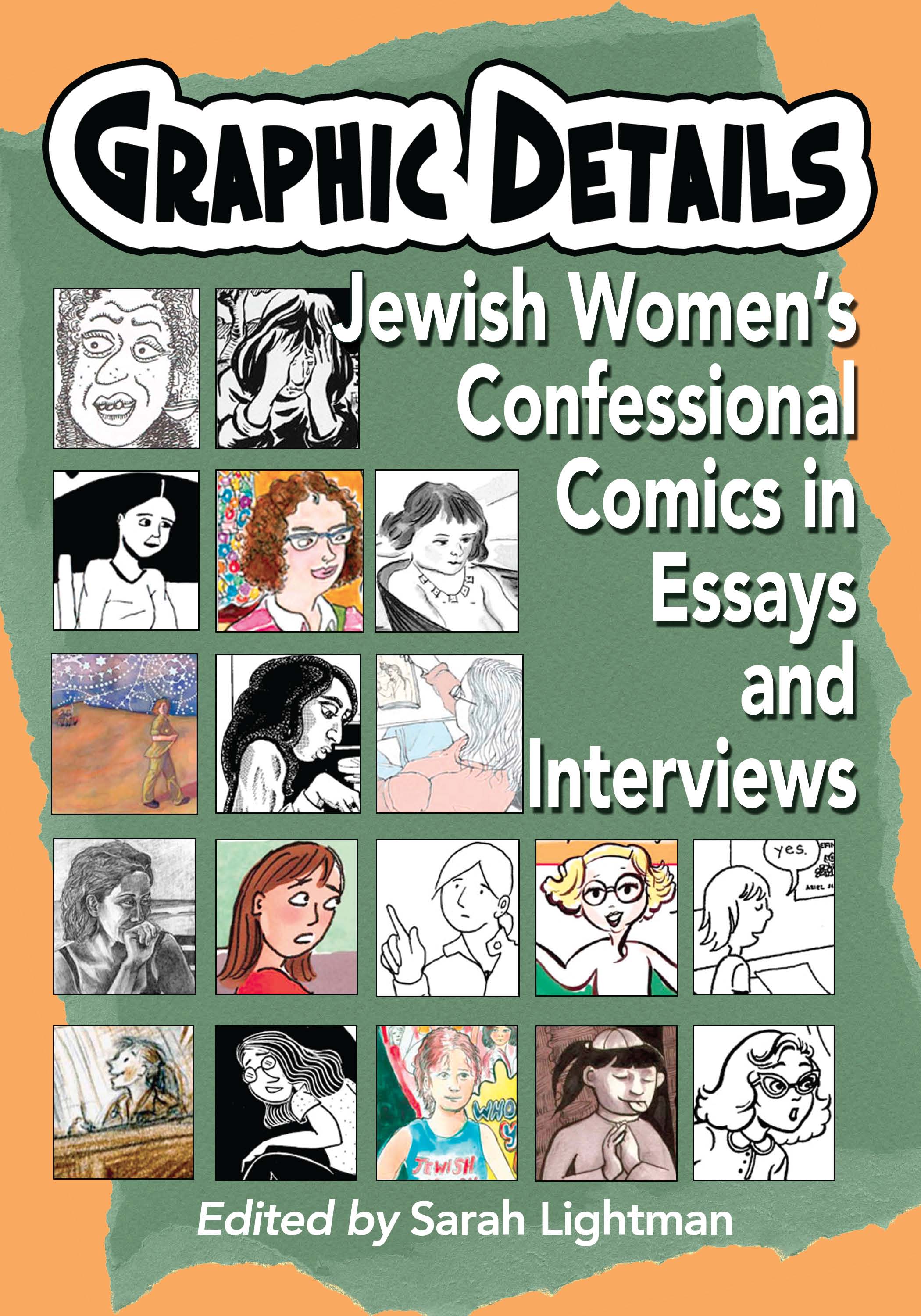

All the comedians I spoke with, in one way or another, addressed political, social and cultural expectations that come with being female. Likewise, Sarah Lightman’s recent edited collection, Graphic Details, Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews, ruptures the comic genre by exposing us to the often marginalized voices of women comic artists. In doing so, it shatters the long-held belief that comics are a (Jewish) man’s game.

In a scene of Comic Book Confidential, a documentary about the rise of American comic book culture, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Maus, Art Spiegelman, gives a speech honoring iconic cartoonist Will Eisner. He argues that Jews are not simply the “People of The Book,” but are “the People of the Comic Book.” As Paul Gravett, comics scholar and recent curator of the British Library’s exhibit, “Comics Unmasked,” notes: “The impact of Jewish creativity and intellect on the foundation of the comic book as an art form . . . is well attested.” By contrast, the impetus for Lightman’s collection emerged from a rather innocent question asked of Lightman at a conference: “Are there really any Jewish women comic artists?”

It was a fair question, given the dominance of Jewish male comic artists. That dominance began with what is considered to be the first Jewish confessional graphic novel, Will Eisner’s A Contract with God. Readers are likely familiar with Spiegelman’s Maus, Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor, and the Golden Age progenitors of the genre, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Superman and Jack Kirby’s Captain America, but not so much with women artists like Aline Kominsky Crumb, Ariel Schrag, Diane Noomin, Ilana Zeffren, Miss Lasko-Gross, and Sarah Glidden. Lightman’s collection, which is based on an internationally touring exhibit she co-curated with Michael Kaminer, exposes readers to women writers and artists whose work has been undervalued and marginalized. In large part, women artists have traditionally been excluded from conventional forms of publishing and marketing, and, therefore, have engaged in more guerilla, underground forms of publication—such as web-based blogs and self-publishing platforms—extending their reach in inventive ways. The original exhibit also allowed Lightman to give voice to her religious background and personal history. The battle cry of the 1970s feminist moment was “The Personal is the Political,” and this collection embodies the notion that Jewish women’s confessional comics contributes not merely to our understanding of women’s lives, but to the burgeoning comics genres as a whole.

The collection is a strongly eclectic mix of scholarship, interviews with the artists and displays of their comic art work, organized around four distinct parts. Part I, “Introductions,” explores the history and culture of the artists, providing a scholarly framework to the collection. For instance, in the essay “Graphic Confessions of Jewish Women Exposing Themselves through Pictures and Personal Stories,“ Michael Kaminer sets the tone of the book by arguing that “women have become a formidable presence in comics,” and the sections that follow Kaminer’s essay rely on that assertion.

In Part II, “Essays,” Lightman creates two sub-sections: “Herstory of Jewish Comic Art,” which examines Jewish women’s confessional identity (including Lightman’s own triptych, “Dumped before Valentines [Day],” where she presents three drawings that concisely “present my changing social status as I became unwillingly newly single, just before the international day of romantic love”). The second section, “Our Drawn Bodies, Our Drawn Selves” is Lightman’s wink at the famous 1970s feminist tome Our Bodies, Our Selves, the first book of its kind to talk frankly about women’s sexuality and abortion. This section fearlessly explores previously taboo women’s topics like miscarriages and lesbian desire.

But the strongest section by far is “Comic Comedy.” The essays in this area examine the nature of Jewish comedy and how it manifests itself in the work of several artists. The comics here are sometimes raunchy, nearly always funny, and in the true spirit of confessional memoir, exposes the reader to intimacy that makes us cringe. For instance, contributor David Brauner’s “The Turd That Won’t Flush: The Comedy of Self-Hatred in the Work of Corrine Pearlman, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Miss Lasko-Gross, and Ariel Schrag,” looks at scatological humor and the struggle to frame adolescent identity. Moreover, the essays here articulate Jewish humor and its components: self-deprecation, anti-Semitic stances, obsession and the familiar Woody Allen trope of neurosis.

Part III is a section on ”Interviews,” which provides the reader with insights into the writer and illustrators who address how their Jewish identity figures into their work and into larger conversations of gender and genre. Finally, Lightman’s last section, “Graphic Details,” illustrates the artists’ work and provides analysis of the pieces.

Ultimately, this collection succeeds because it subverts the male gaze: Instead, these Jewish women artists and writers look inward. These women tell their own stories. Their raw confessional comics are creating a revolutionary way for us to recover the hole in the bagel, recognizing the absence in the genre that we weren’t even aware was missing, and while the artists are diverse in sexuality, age, region, and religious affiliation, the shared commonality of grappling with Jewish identity, simultaneously disavowing and embracing Jewish culture, adds immeasurably to the complex web of Jewish comics and graphic novels.

Andrea Greenbaum, professor of english at Barry University in Miami Shores, Florida, where she teaches classes in fiction writing, cultural studies, gender, multimedia writing, and screenwriting. She is also the Director of the Professional Writing Program. She has published four books: Judaic Perspectives on Rhetoric and Composition, Jews of South Florida, Emancipatory Movements: The Rhetoric of Possibility, and Insurrections: Approaches to Resistance in Composition Studies.