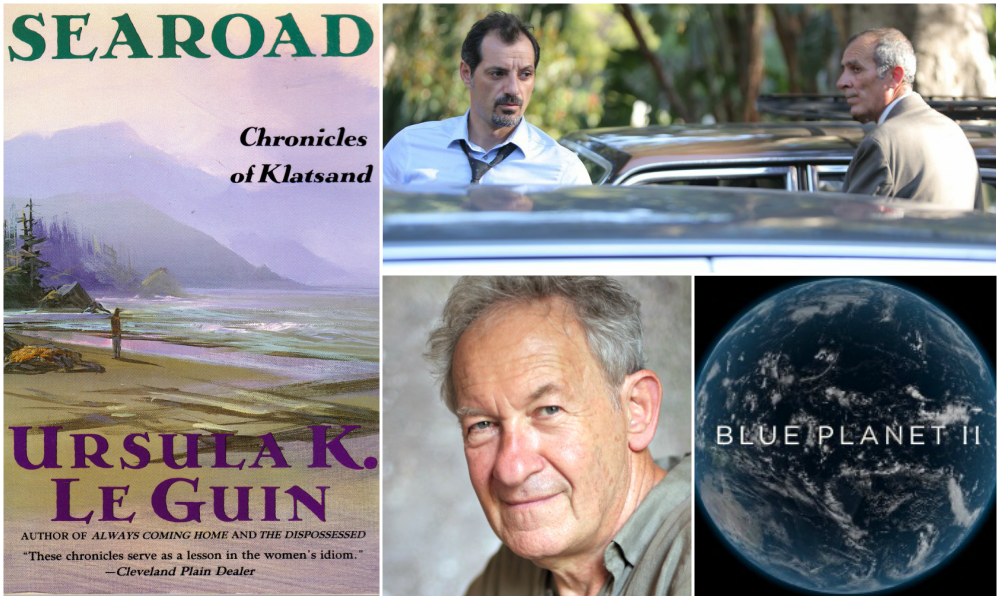

“THE INSULT,” BY ZIAD DOUEIRI

Two men fight over a broken gutter in need of repair. Words are spoken, a punch is thrown and eventually an insult is hurled that is so offensive it could ignite a war in a religiously fractured country. That’s the premise of The Insult, a gripping new film from Lebanese director Ziad Doueiri, that proves once again that in the Middle East the personal is not just political—it’s historical. In Beirut, Toni (Adel Karam), a Lebanese Christian car mechanic, is introduced as a gentle family man, so it is a surprise when he greets Yasser (Kamel El Basha) with so much hostility when the construction foreman appears at his door. Then we learn Yasser is a Palestinian Muslim who lives in a refugee camp and Toni listens to the historical speeches of Bachir Gemayel—the assassinated anti-Palestinian Christian leader—in his spare time. Their conflict escalates to courtrooms, media frenzies and eventually leads to riots in the streets. As the situation spirals beyond their control, it is a credit to the two actors that neither man comes across as foolish in his stubbornness but rather as individuals who have reached their breaking points after years of accumulated indignities.

“Like the Jews say, the Palestinians never miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity,” Toni tells Yasser patronizingly. And while Israel is not part of this film, in some ways it is everywhere—the reason Palestinians are in Lebanon in the first place, a way to slander an enemy and even the insult of the film’s title is centered around a famous Israeli general. Midway through the film, Toni finds his garage destroyed and a Star of David spray painted on the wall as a sign of his collaboration with the enemy. Doueiri has been similarly accused of disloyalty when he shot parts of his 2012 movie The Attack in Tel Aviv. The film, a portrait of an Arab-Israeli doctor dealing with the aftermath of his wife’s terrorist attack, was banned in 22 Arab countries for its “ties” to Israel. When Doueiri, who now lives in Paris and holds U.S.-French citizenship, returned to Lebanon to film The Insult he was arrested and brought before a military tribunal (and eventually released). And despite the fact that The Insult has given Lebanon it’s first Oscar nomination for best foreign-language film, he remains unpopular in his native country. The Insult has the familiar beats of a classic American courtroom drama. But unlike the American iteration (think A Few Good Men), The Insult has no obvious “good guy” to root for or “bad guy” to rail against, making it about as Middle Eastern as it gets. —Sarah Breger, Deputy Editor

“SEAROAD: CHRONICLES OF KLATSAND,” BY URSULA K. LEGUIN

When I heard that Ursula K. LeGuin had died, my first thought was to reread her classic The Left Hand of Darkness—a beautiful story, published in the 1970s but prophetic of today’s interrogations of the gender “binary,” set on a planet where people are genderless except during monthly estrus, when they may become either male or female (afterwards reverting to neutral). But as it happened, I had just reread it, after pulling it off the shelf to recommend it to a high school student. So instead I dug around my house until I found an unread Le Guin, one of her lesser-known books, Searoad: Chronicles of Klatsand, a volume of linked short stories published in 1991. This one is set on Earth—on the Oregon coast, to be specific, in a small beach town whose inhabitants consider it “the end of the world.” It has all Le Guin’s delicately drawn landscapes and gentle loners, plus some wicked feminist asides. My favorite: One of the loners, a woman who’s never felt the need to marry, considers what might have driven women in earlier eras to do so, and hypothesizes, in a clever twist on St. Paul, that women alone were often suspected of witchcraft and must have concluded that “it was better to marry than to burn.” Anyway, anything of Le Guin’s is worth revisiting, and some will probably be reissued. —Amy Schwartz, Opinion Editor

BLUE PLANET II

BLUE PLANET II

One of the most beautiful things I’ve ever seen on television happens halfway through the first episode of Blue Planet II: A fever of mobula rays gracefully twist and turn through layers of bioluminescent plankton somewhere in the deep ocean. Their tails and wing tips create sparks of light in the pitch black—only visible thanks to new technology. It was mesmerizing—more like a ballet or experimental film than a nature documentary. The final act of episode one was incredibly emotional and more familiar: It focused on the bond between a mother walrus and her pup, as they desperately try to find rest on an (increasingly rare) ice float. The Atlantic calls Blue Planet II “the greatest nature series of all time.” Episodes one, “One Ocean” and two, “The Deep,” are available now. “Coral Reefs” airs this Saturday on BBC. —Navid Marvi, Art Director

FROM DARKNESS: SIMON SCHAMA ON HUMAN ADVERSITY AND THE ORIGINS OF GREAT ART

FROM DARKNESS: SIMON SCHAMA ON HUMAN ADVERSITY AND THE ORIGINS OF GREAT ART

This thought provoking article, “From darkness: Simon Schama on Human Adversity and the Origins of Great Art,” is published just ahead of a new nine part series entitled “Civilisations.” The TV program, broadcast initially on the BBC, will examine “the messy story of human lives—war, love, power—through humanity’s masterpieces.” Schama reminds us of when Kenneth Clark, in the original 1969 series, turned to the camera and asked “What is civilization? I don’t know…but I think I can recognize it when I see it.” Schama posits that Clark focused on “European genius” while the upcoming BBC series will offer a fresh perspective—that of the cultural creativity which flourished when European artists came into contact with the non-European world. He, together with co-presenters Mary Beard and David Olusoga, offers multiple instances. For example, the art of Tokugawa Japan was affected by the import of Dutch optical instruments, Monet was influenced by the woodblock prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige and Van Gogh said he was seeking “Japanese light” when he moved to Provence in the south of France. The series does not, he says, short change “the glories of the west,” though he suggests that academics, to the detriment of the teaching of the history of art, tend to be “ghettoized,” and hence concentrate only on their own specialist areas of knowledge. Schama offers a tour d’horizon of art history and notes “it has been striking how often a period of great creative energy either followed a period of calamity or was produced as a response to it.” But back to the question of “What is civilization?” Mr. Schama offers us his own answer. It is horrifying—yet deeply poignant. For him it is a collage, made by 12-year-old Helena Mandlová in the Theresienstadt concentration camp, and which now is in the Jewish Museum at the Pinkas Synagogue in Prague. Twelve-year-old Helena was one of 15,000 children separated from her family and put in “horrifyingly overcrowded, disease-ridden barracks.” While incarcerated, she created a night landscape using white office stationary and, as Schama so eloquently writes, “the sheet is not some enumeration of transports east, one of which would carry Helena (like 90 per cent of the Theresienstadt children) to her death in Auschwitz, but simply some piece of dull bureaucratic supply of the kind needed by those who managed the efficient business of mass extermination. But for a moment, Helena had cleansed the sheet of its moral dirt. She had made art.” Helena’s art teacher, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (herself murdered in Auschwitz), had taken art materials with her to Theresienstadt in late 1942. She had told her pupils, all aged between 9-13, to sign their paintings for posterity (4,500 pieces of art and sculptures were found in two hidden suitcases). She had shown the children photos of paintings by Vermeer and Raphael and these were echoed in some of their artwork. “Thus civilization came to the inferno, fighting back hard for humanity.” —Dina Gold, Senior Editor

FINDING YOUR ROOTS

FINDING YOUR ROOTS

Gaby Hoffman, star of HBO’s Transparent and former child star of a string of hit movies including Field of Dreams and Sleepless in Seattle, appears on PBS’s Finding Your Roots. In the episode, Gaby is able to find out that her great-grandfather was French and abandoned his wife and child in order to return to France to fight in World War I. Her grandfather got hurt in the war and then had an affair with his nurse. Gaby herself did not grow up with her own father, Anthony Herrera, who was also an actor. Her actress mother, Janet Sue Hoffman, was one of Andy Warhol’s muses he called “Viva.” Gaby had a fascinating upbringing in New York with artists and actors, but the show does not get into that much. The focus is finding Gaby’s unknown past—and in the end of the episode, through Gaby’s DNA testing, she finds out she is royalty! I don’t want to ruin all the details! —Johnna Raskin, Events Manager