This article was originally published in the October 2002 issue of Moment

Mr. Jones is annoyed. He motions the waiter back to his table.

“Taste the soup!” he commands.

“Whaddya mean? ‘taste the soup?'” asks the waiter.

“Taste the soup,” says Jones.

“It’s cold? I’ll get another bowl.”

“Taste the soup!”

This continues for several moments until the waiter finally relents, figuring he’ll humor the guy.

“All right, all right; I’ll taste the soup.”

The waiter approaches the table and fruitlessly searches the place setting for the proper utensil. He throws up his hands.

“Where’s the spoon?” he asks.

“Aha!” Jones says triumphantly.

Jones could just as well be Cohen. By any other name, this is a Jewish joke. What makes it Jewish? The customer’s devilishly circuitous, almost Talmudic way of making a point. The undercurrent of subversiveness. The food. You name it: They all conspire to infuse the joke with a certain intangible quality. But who needs a fancy shmancy discourse to determine if a joke is Jewish — or funny, for that matter? Not us. Jews know funny the way Eskimos know snow. We are, after all, the People of the Punchline. Aren’t we?

Indeed, in 1979 Time magazine, the quintessential barometer of American life, told the nation that even though Jews made up only 3 percent of the population, 80 percent of America’s working comedians were Jewish. Not that the public really needed to be reminded. They had laughed at Joan Rivers’ take on the role of women: “I hate housework. You clean the dishes. You make the beds. And a month later you have to start all over again.” They had chuckled along with Woody Allen’s urbanized intellectual schlemiel who confessed to cheating on his metaphysics exam “by looking into the soul” of the student next to him. They had guffawed as Rodney Dangerfield plumbed new depths of necktie-yank-ing self-deprecation: “I don’t get no respect,” he’d say. “Last week I met the surgeon general, and he offered me a cigarette.”

Rabbi Bob Alper, who now works mostly as a comedian, bills himself as “the world’s only practicing clergyman doing stand-up comedy … intentionally.” He says, “People accuse Jews of being funny. If you have to have a stereotype, that’s not a bad one.”

Now, though, it appears that stereotype may be dated. Jews don’t seem to dominate comedy as they once did. What happened?

Since that era of overwhelming Jewish influence deeply and successfully into American society, an immersion exemplified most dramatically by the number of them who; intermarry, disperse geographically, and otherwise; fade into white-bread American society.

Assimilation has also meant that Yiddish, the fertile soil that allowed much Jewish humor to blossom, has been lost to many Jews. Reb Moshe Waldoks, coeditor with William Novak of The Big Book of Jewish Humor, suggests that Jewish comedians can’t be as funny without Yiddish, the insiders’ tongue. “When the comedians used English, and American audiences understood everything, the comedians became inhibited.” After all, “Yiddish allowed a certain amount of anti-goyism and self-criticism. The Jewish comedians felt free to be self-critical when their observations couldn’t be used by outsiders against the Jews.” He also notes that the audience immediately got the jokes because they shared so many common experiences. “When you got up in front of a crowd of Jews, you knew they understood.” The fact that the Jewish audience immediately grasped some material that others wouldn’t gave an earlier generation of Jewish comedians a place to be safe and develop their craft. Once the comedians had to venture forth from, say, the Catskills, they had already played in front of tough, demanding, intelligent audiences.

The language they shared was noteworthy, and not only because it communicated common experiences. Yiddish itself is intrinsically funny, what with its elaborate curses (“all of your teeth should fall out, except one, and that one should ache”) and its penchant for cultivating an incisive, dark-edged, altogether cock-eyed view of the world. The language of lament, myth-busting, and belly-laughing, Yiddish is the tongue of the underdog, the outsider, and the sad but wise survivor who laughs to keep from crying.

Yiddish had a sardonic tone, as when legendary raconteur Myron Cohen would tell a signature story in a lilting Yiddish-tinged accent.

He was sitting on an airplane next to a woman who was wearing a large diamond.

“Excuse me,” he said. “I’m not trying to be forward, but that is a beautiful diamond.”

The woman nodded. “It’s called the Klopman Diamond. It’s like the Hope Diamond. It comes with a curse.”

“What’s the curse?”

“Klopman.”

Some Jewish jokes grew out of an earlier atmosphere of friendly hostility between Jewish men and women. Consider, for example, Henny Youngman’s rapid-fire repertoire: “My wife will buy anything marked down. Last week she bought an escalator. My wife said she wanted to go someplace she hadn’t been before, so I took her to the kitchen. I went on a pleasure trip. I took my mother-in-law to the airport.” Youngman, and many other male Jewish comedians, depended on audiences having a particular view of Jewish women for their acts to work.

Today, though, the dynamic between Jewish comedians and their audiences has changed. Alper says this is in part because of intermarriage. Audiences are afraid to laugh at jokes about the subject. Because so many American Jews are intermarried, it’s a challenge for Jewish comedians to find ways to joke about the subject. Precisely because they don’t want to alienate a large segment of the Jewish audience —and because members of the gentile audience are often not aware of the controversy — Jewish comedians, who once could reliably find in the adventures of Jewish life an inexhaustible source of humor, are now constrained in their use of material.

Meanwhile, Jews are decreasing as a percentage of the American population, they are older, and the last generations that were nurtured on Yiddish and immigrant humor are disappearing. As Stephen Rosenfield, a comedy coach in New York, puts it, “There was once a very sizable market for Jewish comedians doing specifically Jewish material. The Catskill audience is practically nonexistent.” Neil Leiberman, a San Francisco-based comedy coach, tells even his students who are Jewish “not to concentrate on ethnicity. Make, at most, only a quarter of the act ethnic.”

Meanwhile, there’s far more competition for the mike than ever before. Comics from all sorts of ethnic and socio-economic groups now vie for the spotlight. As the comedy pie has gotten bigger, the Jews’ proportionate slice of it has shrunk. “At first, in the late ’80s, practically everybody was Jewish,” says Judy Carter, a comedy coach in Los Angeles and the author of The Comedy Bible. “Then there was an influx of Catholics. At first, they had a fear of revealing themselves. Then in the ’90s, gay comics came out. Lately, there have been a tremendous number of Asian comics.”

But the Jews were the trailblazers. It was primarily the Jewish comedians, after all, who had demonstrated that the WASP hinterland would laugh with and not just at the “other,” would tune in to hear or pay for jokes about worlds other than their own. The Jewish willingness to confess was, as Carter noted about Catholic comedians, crucial in providing emotional permission for all comedians to reveal deeply personal information on stage.

The Jews were themselves willing to confess because they came from a tradition that prized honesty, that nurtured the idea that it was healthy to express feelings, that used the language of confession because alternate forms of changing reality were unavailable to a powerless people. Lenny Bruce was perhaps the most famous of the comedians who began metaphorically undressing themselves on stage. He’d talk a lot about being Jewish, such as in his famous series of distinctions about who’s Jewish. He deliberately used the term goyish to describe gentiles: “I’m Jewish. Count Basie’s Jewish. Ray Charles is Jewish. Eddie Cantor is goyish … Hadassah, Jewish. Marine corps—heavy goyim, dangerous. Pumpernickel is Jewish.”

A penchant for questioning authority is another key comedy ingredient, according to Carter, and Jews certainly have a history of challenging their superiors. The children of Israel constantly griped and nipped at Moses’ heels. The Talmud leaves little unquestioned. As for Carter, she gleaned from her grandmother’s Passover seders that a person learns by asking questions. Gentiles, Carter notes, had been taught just to listen and accept, but they learned from the Jewish comedians that it was all right to speak truth to power.

Likewise, even though Jews have largely joined the upper- and upper-middle classes, they’ve somehow retained an ability to identify with the underdog. This has enabled them to stand outside the inner circle so as to see the ordinary in a skewed way and therefore identify what’s funny.

Perhaps because of this outside-looking-in perspective, Jewish humor, in this post-Seinfeld era, continues to be universalized. Jewish jokes and other forms of shtick are now used not only by Jewish comedians, but also by many gentile comedians. And that shouldn’t come as a surprise. Leiberman notes that American audiences are now so familiar with Jewish-style humor—self-deprecation, darting observation, fast talk—that they are comfortable with it, and to some extent, even expect it from gentile comedians. That is, the taste for comedy grounded in Jewish tradition has not disappeared at all; it’s simply being diffused.

An example: Alper has toured with Ahmed Ahmed, an Egyptian-bom Arab comedian, who even sprinkled some Yiddish into the controversial act as he poked fun at being an Arab in post-Sept. 11 America. During one of their gigs, Ahmed (presumably shifting back to English) tells of showing up at the airport “a month and a half early” to go through security.

Fine, but if a Jew walks into a bar, will a good punchline still follow him out? In short, are there any reasons to be optimistic about the future of Jewish comedy? As it happens, there are.

For example, there are plenty of new places for potential Jewish comedians to practice comedy, even if there is no Catskills to serve as a training ground. As Rosenfield points out, “Before 1970, there were night-clubs but no comedy clubs. Now comedians can work in a lot of places that didn’t used to book them, places like bookstores, synagogues and churches, co-ops in Florida, cruise ships, and elsewhere.” This wide range of venues, however, can make life complicated for comedians. Rosenfield notes, “There are comics who have Jewish material for synagogues or singles groups or in comedy clubs. But they have very different material for late night, when there is more blue material.”

Waldoks’ optimism has a different source. “There is a sense of Jewish revival. We are now creating a new community. You can see it in Jewish camps, in synagogues, and elsewhere. Jewish humor isn’t in the hands of professionals, but is becoming more folk-centered, more insider. It is back where it all began. These insiders have a Jewish knowledge base that allows them to create jokes that will be understood by the audience.” That is, the older Jewish audience—the Yiddish-based audience—is declining, but it is being replaced by a smaller Jewish audience widi not so much a cultural as a religious commonality. This means there will be more humor based on religion. It is not surprising, therefore, that there are an increasing number of synagogues that have Purimspiels—the often wine-enhanced Purim skits and plays that started in the Middle Ages performed by Jews dressed in costumes and masks.

In the larger sphere, though, any comedian must be able to address the particular, fleeting emotional needs of an audience and Jewish comedians are no different. All Americans are familiar with many comedians who succeeded for a while, only to fade (think of, for example, George Jessel). They didn’t stop being funny; they stopped being the most in tune with audience tastes. Jewish comedians succeeded because they understood the symbiotic relationship that must exist between performer and audience.

From time to time, Jews have connected with audiences by serving as a surrogate outlet for their frustrations and insecurities. Consider the immigrant experience. At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, America was awash with immigrants from abroad as well as “internal immigrants,” who had moved from America’s farms and small towns to the cities looking for work. Both sets of immigrants felt foreign, excluded, and insecure. They needed an emotional release. What people in history was most experienced in moving to new places and adapting quickly? To ask the question is to answer it. The Jews had the emotional background to identify with the downtrodden.

The Marx Brothers, for example, were not just hilarious, but they developed the survival strategy of immigrant adaptation by mocking the institutions that were feared. Groucho’s wisecracks, Chico’s cons, and Harpo’s silent innocence allowed immigrant audiences to laugh at the rich and powerful, at high art, and higher education. Many of the Marx Brothers’ routines were about those on the outside trying to get inside. Consider, for example, this scene from Horse Feathers:

Cliico: Who are you?

Groucho: I’m fine, thanks, who are you?

Chico: I’m fine, too, but you can’t come in unless you give the password.

Groucho: Well, what is the password?

Chico: Aw, no! You gotta tell me. Hey, I tell you what I do. I give you three guesses … It’s the name of a fish.

Groucho: Is it Mary?

Chico: Ha! Ha! Attsa no fish.

Groucho: She isn’t. Well, she drinks like one …

Chico: Now I give you one more chance.

Groucho: I got it. Haddock.

Chico: Attsa funny. I gotta haddock too… You can’t come in here unless you say “swordfish.” Now I give you one more guess.

Groucho: Swordfish … I think I got it. Is it swordfish?

During the Great Depression, American audiences turned to Jack Benny for solace. Benny was famous for several characteristics, including his cheapness. He would say he couldn’t afford flowers for his date, so he bought her seeds. Once, he was asked to throw out the first ball at a World Series game, but he looked at the ball, stuck it in his pocket and sat down. The crowd roared. This trademark characteristic, however, allowed poverty-stricken listeners to laugh at their own condition and find some relief from the guilt they felt when they couldn’t properly provide for themselves or their families.

But unlike Benny—and others of his generation—today’s young Jewish comedians are more comfortable performing openly as Jews. Jack Benny had to change his name from Benjamin Kubelsky to succeed. And he wasn’t the only one who had to homogenize. George Burns wasn’t always George Burns. And Rodney Dangerfield was born Jacob Cohen.

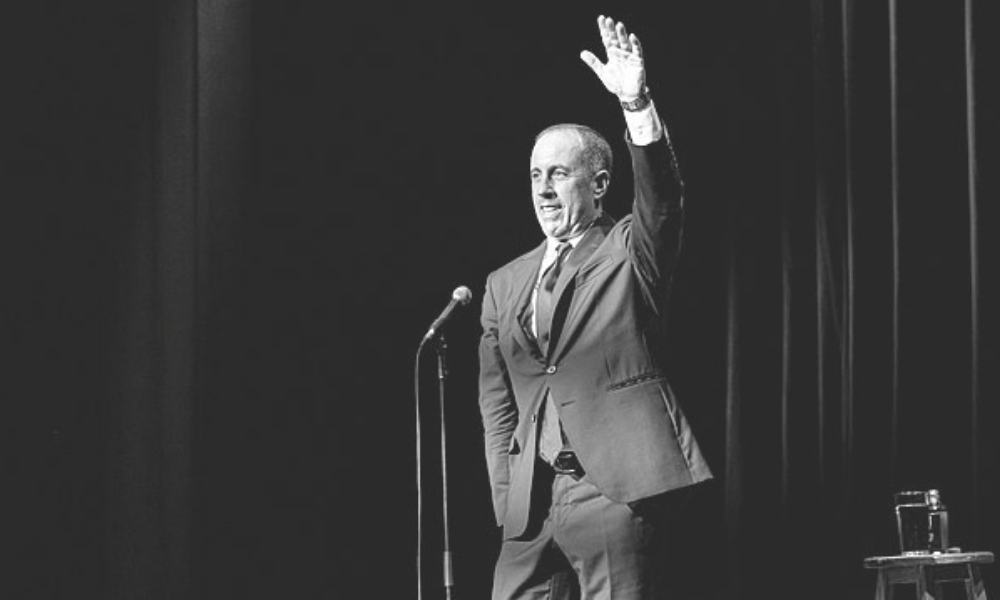

The need to change names has, of course, changed. Jerry Seinfeld never had to de-Judaize his name or that of his show. That fact alone illustrates how far Jewish comedians—and Jews as a whole—have come. But, hard as it is for Jewish audiences to believe, not all of Seinfeld’s audience realized he was Jewish, so conditioned were they to Jewish humor. Indeed, on the show, Seinfeld only once announced his Jewishness—to a priest in a confessional to whom he’d gone to complain that his dentist became Jewish only for the jokes. (Kramer accused Jerry of being an “anti-dentite.”) Adam Sandler’s clever Hanukkah song, with its sorting out of who’s Jewish and who isn’t, could never have been presented to a mass audience 50 years ago. Today, American audiences love it.

Sandler and Seinfeld (who, alas, is now found mainly in reruns) aren’t the only Jews who are still funny, though. There is an impressive lineup of young Jewish comedians waiting in the wings. Some are very well known, such as Ben Stiller, Sandra Bernhard, and Jon Stewart. Others are known to more limited audiences, but might become household names if they get a big break. Among the rising stars of the many talented younger Jewish comedians are Lewis Black, Scott Blakeman, Judy Gold, Cathy Ladman, Wendy Liebman, Jeffrey Ross, and Sarah Silverman. Jewishness is incidental for many of the stage personas of contemporary comedians, though Jeffrey Ross does make a point of playing Jewish sites, and Scott Blakeman makes a point of mentioning his Jewish identity in his act.

Meanwhile, it’s noteworthy that no Israeli comedians have made it big in the United States. It’s not that Israeli comics aren’t funny—nor that the Jewish State isn’t fertile ground for laughs, despite the depressing political situation there. It’s just that, when it comes to humor, context is everything.

Just ask Einat Temkin, 28, a sabra who spent two years in the military and is now getting her Ph.D. in communications at the University of Southern California. She’s also studying with Judy Carter and is trying to make it as a stand-up comedian. She is intimately familiar with the differing comedy traditions of Jews in American and Israel. “We had no vaudeville,” says Temkin. “There was no old-school comedian. Our stand-up comedians are young and take risks. The humor is sarcastic and edgy.”

Because comedians draw on their shared experiences with the audience, an Israeli comedian in Tel Aviv can tell a lot of jokes about military life, an experience with which most Americans are much less familiar. “The military is exotic here,” explains Temkin. “Also, in Israel there is a lot of ethnic-oriented humor, such as about the differences between Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews.” Clearly, this is not a subject that’s prominent in American Jewish life.

There’s a very active humor tradition in Israel, though, even if it hasn’t yet reached the American shore. The comedy show Rak B’Yisrael (Only in Israel) attracts a half-million viewers each Friday night with its satire and timely skits. Grim jokes laced with black humor routinely make their way through Israeli society, such as a recent joke in which one friend, planning to meet another, says, “Let’s pick a cafe that won’t explode.” Of course, the humor is not always grim. There are always jokes like, “Did you hear that Yasser Arafat wants to convert to Judaism? One thousand mohels requested the job.”

Take Israeli service … or lack thereof. It was mealtime during a flight on El Al.

“Would you like dinner,” the flight attendant asked the man seated in front.

“What are my choices?” he asked.

“Yes or no,” she replied.

Back in America, the new Jewish comedians may have a special role to play in contemporary American Jewish life, just as they played a significant role in helping gentiles in America come to understand their new Jewish neighbors and help greenhorn Jews to navigate the often confusing waters of American culture, and the Jews who came to the Catskills master the art of leisure. Maybe Jewish comedians can help guide Jewish audiences as they search for ways to deal with the unique current challenges of Jewish life—including the anxiety and tension involved in continuing to choose a Jewish identity when so many other identities are available. Maybe these new Jewish comedians will find in the emerging realities of American life an emotional touchstone in Jewish tradition and use that tradition to help all Americans laugh through their tears. In doing all this, the Jews will be doing more than simply being funny. Far more importantly, they will still be Jews.

Top photo: Jerry Seinfeld. Credit: Wikimedia