____________

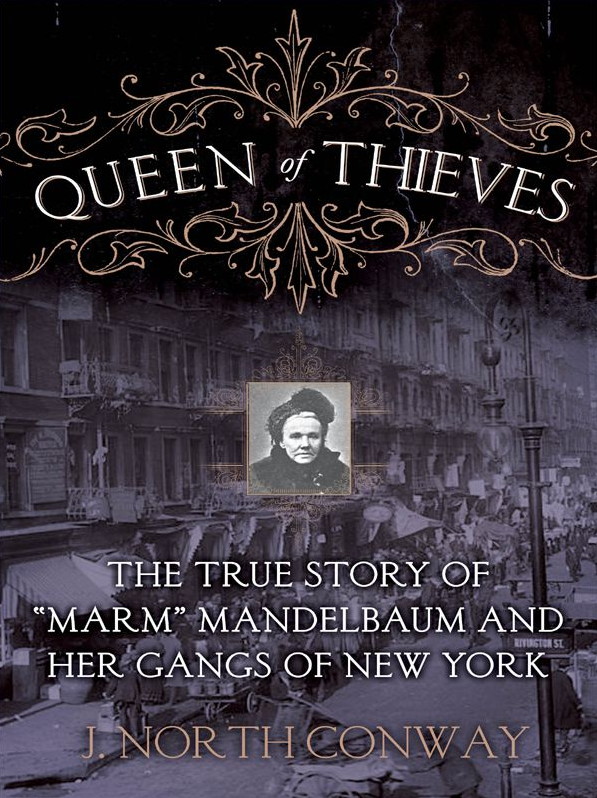

Queen of Thieves: The True Story of “Marm” Mandelbaum and Her Gangs of New York

J. North Conway

Skyhorse Publishing

2014, pp. 240, $24.95

A Fence Called Marm

by Sam Roberts

She was an immigrant folk hero, an interloper in respectable society, a female Fagin and America’s most notorious 19th-century fence. The lack of a modern, full-fledged biography of “Marm” Mandelbaum—until now—is a tremendous oversight.

Born Fredericka Mandelbaum in Prussia in 1827, “Marm”—short for “mother,” because she presided over a brood of fledgling crooks—finally gets an earnest and well-researched effort in Queen of Thieves: The True Story of “Marm” Mandelbaum and her Gangs of New York, by J. North Conway.

Conway, the author of a dozen books, including a trilogy on Gilded Age New York, introduces readers to Mandelbaum’s florid associates and revisits a cast of her contemporaries. They include Police Inspector Thomas Byrnes, her lawyer William Howe and prosecutor Abraham Hummel, Boss Tweed and his cronies and the Pinkerton gumshoes, father and son, in a rollicking tale that works best when it speaks for itself.

This reader was left longing for at least excerpts from the transcript of Mandelbaum’s courtroom appearances. And the telling of this lively tale suffers from sometimes clunky narration and careless repetition, plus awkward interspersing of the author’s text with original excerpts from newspapers and other accounts.

Still, this literary buffeting is a relatively small price to pay for a priceless yarn, drawn from a plethora of recent and 19th-century sources (listed in a hefty bibliography that includes an often-quoted 2007 doctoral dissertation by Columbia University’s Rona Holub).

If Conway sometimes seems to echo lenient apologists for nonviolent criminal behavior, he diligently tries to place Mandelbaum’s professional pursuit in perspective: “Her immersion into a life of crime, as opposed to one of legitimacy, was a backlash against the cruel treatment she and her husband had endured at the hands of German authorities before being forced to immigrate to America. That abuse and distrust of authority kept her on the wrong side of the law throughout her life.” She also realized, Conway writes, that a woman, no less a Jewish woman, given mid-19th-century prejudice, could never find acceptability or the kind of wealth and power she attained in any legitimate business.

Mandelbaum more than merely crossed the line into crime. In 1884, The New York Times called her “the nucleus and center of the whole organization of crime in New York City.” Even physically, she was a formidable figure: nearly six feet tall and 300 pounds (but still managing to elude a stakeout and escape to Canada).

And she pursued her profession in a moral climate of Civil War profiteering and Gilded (read “veneer”) Age extravagance. “Mamie” Fish, wife of Stuyvesant Fish, a railroad baron and descendant of the Dutch mayor, presented her dog with a $15,000 diamond collar at a time when, Conway writes, “to say that the country’s rich obtained their great fortunes legally is a stretch.” He adds: “This in no small way contributed to the public support of Mandelbaum and her ilk for being champions of the lower class, since they defied the laws—the laws that the rich broke for their own gain.”

Mandelbaum, in effect, conducted a school for criminals and invested in lucrative crimes, but she was primarily a fence. According to one account, the term dates from the 18th century and defines the practice of selling and buying stolen goods at a deep discount—without asking too many questions about their origins—and reselling them at near-market prices, sometimes even to the victim of the theft.

“It is really the root of evil, but the suppression of receivers of stolen goods in the State of New York owing to existing laws, has been almost an impossibility,” Police Inspector Thomas F. Byrnes, chief of the Detective Bureau, wrote in 1886.

And among the nation’s fences at the time, Mandelbaum was indubitably the queen. “She is known, at least by name, to every thief and detective in the United States,” Robert Pinkerton said in 1884, “and has received plunder from nearly every city in the country secured by traveling gangs of professional thieves.”

After she was finally arrested in a sting that year, she was defended by William Howe, whom The Times described as “a Maypole of more than ordinary circumference.” On the stand, she described herself as a 52-year-old widow who lived at 79 Clinton Street on the Lower East Side. “I buy and sell dry goods as other dry goods people do,” she testified.

But on December 4, 1884, the morning her trial was to begin, she had vanished. “I believe,” Howe informed the court, “Mrs. Mandelbaum acted upon Mark Twain’s theory that absence of body is often better than presence of mind.”

Employing a body double, which in her case took considerable ingenuity, she had escaped to Hamilton, Canada—after first transferring her assets to protect them from bail forfeiture. She opened a store and supported her local synagogue, but obviously was no fan of Canada. “The name of the place is enough to sicken me,” she said. She returned to New York only twice, however, for her daughter’s funeral in 1885, without being rearrested, and then in 1894, only after her death at the age of 65.

A German-language daily newspaper advocated for a plaque in her name on the Lower East Side. “This would have greatly pleased Mandelbaum,” Conway notes, “who probably would have asked who she had to pay off in order to get the plaque erected.”

Sam Roberts, the urban affairs correspondent of The New York Times, is the author of The Brother: The Untold Story of the Rosenberg Case, recently reissued with a new epilogue and, most recently, of A History of New York in 101 Objects.