Hitler’s American Friends:

The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States

By Bradley W. Hart

St. Martin’s/Thomas Dunne Books

2018, 304 pp, $28.99

Four days after Pearl Harbor and the U.S. declaration of war against Japan, Nazi Germany inexplicably declared war against the United States. John Kenneth Galbraith, then a New Deal economist in Washington, later called it “a totally irrational thing for [Hitler] to do…and I think it saved Europe.” But for Hitler’s gratuitous challenge to Washington, Galbraith was suggesting, it would have been possible to imagine a U.S. mobilization limited to a war against Japan, effectively giving a free pass to the Nazis in Europe.

The Nazis’ declaration ended the long debate over U.S. entry into the war in Europe. Young men of the isolationist America First Committee enlisted, or were drafted, into the conflict they had enthusiastically opposed. By the war’s end, little was heard of old pre-war arguments: that the oceans were our only necessary allies, that Britain was done for, that the Jews of Europe were responsible for their own troubles or even that Hitler’s autobahns and aircraft factories showed his national socialism to be an estimably productive and honorable model—one that would serve as a check on Communism and a glimpse of an inevitable new world order.

Such sentiments were common enough in the U.S. to account for Galbraith’s appraisal. They are sentiments advanced by the people and organizations Bradley W. Hart writes about in his compelling and troubling history, Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States. The book is disturbing reading on two counts. First, Hart reminds us of how many Americans found fascism and anti-Semitism either attractive or unobjectionable when those isms were spreading rapidly across Europe. According to a 1939 Fortune poll that he cites, 13 million Americans agreed with the statement that Jews should be deported “to some new homeland as fast as it can be done without inhumanity.” Second, it is impossible to read about the 1930s without comparing those times to today’s Trumpian nationalism and modern-day calls for mass deportations, to be conducted of course “without inhumanity.”

Drawing upon recently opened archives and personal papers, Hart tells the story of such isolationist groups as the German American Bund, the Silver Legion and America First through the experiences and recollections of people who took part in them or worked against them. (The National Archives, he notes, contain many still-sealed documents that could shed more light on Nazi sympathizers.) There are some familiar faces in this rogues’ gallery. There is the much-idolized isolationist aviator Charles Lindbergh, who blamed FDR, Britain and the Jews for advocating entry into the war; the anti-Semitic industrialist Henry Ford, whose European factories churned out trucks for the German Army; the German agent George Sylvester Viereck, who, with the aid of isolationist or pro-German congressmen, disseminated pro-Nazi propaganda; and the “radio priest,” Father Charles Coughlin, a role model for broadcast demagogues ever since. There are also characters who have faded from memory, such as the General Motors executives who lacked scruples about doing business in Nazi Germany, or the Coughlin successor and anti-Semite Gerald Winrod, who lost the 1938 Kansas Republican primary for a Senate seat but received more than 50,000 votes. Hart also recalls Columbia University’s tolerance of fascist speakers (called out by the student paper, The Columbia Daily Spectator). These included the leading American fascist intellectual Lawrence Dennis, an Exeter- and Harvard-educated writer and diplomat who started out as a child preacher in the black churches of Georgia and, after going north, passed as a white man of notably “bronze” complexion.

On the heroic side, Hart writes about the investigative reporter John C. Metcalfe (born Hellmut Oberwinder in Germany), who infiltrated pro-Nazi groups and alerted politicians and the public to the danger they posed. After creating a fake identity to go undercover, Metcalfe reported for the Chicago Daily Times and testified to Congress about the Bund’s true nature. He described hate-filled rallies that he attended in Bund (essentially Nazi) uniform and summer camps where American “Aryan” youths learned the “Four H’s: Health, Hitler, Heils and Hatred.” Hart also recalls the Armenian-American writer Arthur Derounian, who in 1939 infiltrated the New York City Bund and other extreme right-wing groups and published his account in a book titled Under Cover, using the pen name John Roy Carlson.

To use today’s vocabulary, Germans were certainly “meddling” in American politics, but Americans and their allies were aggressive in tracking them down. Some of the keenest work in tracking them was done by British intelligence, also taking liberties on American soil. In June 1940, the fabled Canadian British spy William Stephenson used the diplomatic cover of “passport control officer” in New York City to run the MI6 station out of Rockefeller Center. Stephenson and company stole secrets from the German and Italian embassies and passed stories favorable to the case for U.S. entry into the war to sympathetic American journalists. Through an intermediary—the New York lawyer Ernest Cuneo—Stephenson passed information about the Germans to the popular gossip columnist and radio commentator, Walter Winchell. “In some cases,” Hart writes, “this included information that had not previously been provided to the FBI. Winchell therefore became not only a propaganda tool for the British government and Roosevelt, but also an important intelligence source for the FBI.”

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, at FDR’s insistence, kept an eye on right-wing American groups and did so effectively. In 1941 the Bureau cracked an East Coast German spy ring thanks to a German-American double agent named William Sebold, whom the Gestapo had pressured to spy for them by threatening harm to his family in Germany. Sebold tipped off the U.S. and the Bureau and met with German agents in an office that was “completely bugged.” Both the Bureau and the House Un-American Activities Committee (which hired Metcalfe as an investigator) went on to do much postwar red-hunting (ruining more lives than the charismatic Senator Joseph McCarthy did), but their earlier anti-Fascist work appears to have been substantial and important.

There was, of course, also broader resistance. Public warnings about German “meddling” were frequent. The Jewish War Veterans lobbied hard for adoption of the 1938 Foreign Agent Registration Act, a tool to deport Nazi agents operating in the United States. For all of Father Coughlin’s talents with a microphone, there was Winchell on the other side, and FDR himself was no slouch on the radio.

Calling all the groups treated in the book “Hitler’s American friends” might be too sweeping a statement. The America First Committee was the largest of the groups opposed to U.S. entry in the Second World War. Is it fair to lump its 800,000 members among “supporters of the Third Reich”? True, their opposition to fighting Germany cheered Berlin. But there were motives for isolationism apart from anti-Semitism, admiration for Hitler or opposition to FDR’s New Deal. The memory of World War I, billed as “the war to end all wars,” was relatively fresh, and the state of Europe in the 1930s was a poor advertisement for the promises of what U.S. intervention in the next war might achieve. To rally for staying out of World War II might have required some (perhaps willing) blindness to the genocidal anti-Semitism of the Nazis. But to dismiss America First supporters as “Hitler’s friends” tars the likes of President Gerald Ford, Yale President Kingman Brewster and Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver (all of whom, as young men, supported the AFC) with the less-excusable sins of the movement’s idol, the worldly Lindbergh. They were anti-war. Would we brand Barack Obama one of “Saddam Hussein’s friends” for opposing the war in Iraq?

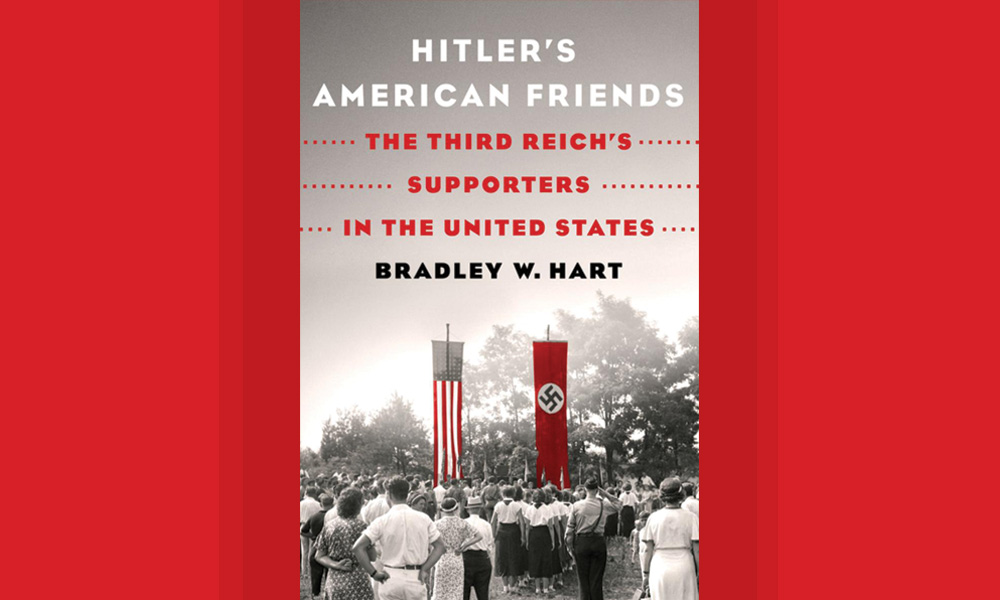

Hart observes that while “Hitler’s American friends” went down to unequivocal defeat, “for a brief period, it appeared that the American flag and the swastika might well end up flying side by side.” His analysis of why it didn’t happen suggests the role played by chance and by individual decisions. The most prominent German American Bund leader, Fritz Kuhn, was undone by his own greed and personal corruption, convicted of tax evasion and embezzlement in 1939. Lindbergh, Hart reasons, was the only figure capable of uniting the American Right. And unlike the fictional Lindbergh of Philip Roth’s novel, The Plot Against America, the real-life Lindbergh did not seek the presidency in 1940. That was the year that FDR, pushing the United States toward entry into the war, sought and won an unprecedented third term. Far from nominating an icon of isolation, Republicans chose an internationalist, Wendell Willkie.

More generally, Hart credits the American political system and its leaders for preventing a turn to the anti-war right—particularly those leaders who, hearing the thunderous cheers at pro-German or anti-war rallies, might have been tempted by the promise of electoral triumph they offered, but who instead ultimately stood up to these would-be American Führers and aspiring American Duces. We would be well-served by political leaders possessed of such stern resolve today.

Robert Siegel was host of NPR’s All Things Considered.

I have read Dr. Hart’s well-written, thoroughly-researched book. It is a persuasive, readable documentation of how the post-WWI sentiment in America was roiled by the turbulent events in Europe during the 1920s and 30s. Professor Hart’s book is a must read for anyone interested in seeing how the darker U.S. history of that time has emerged today.

With every new generation, a new Amalek will rear its ugly reptilian head extruding a bifurcated tongue.

Same as TRUMPS jewish friends… anything for a buck!

Unfortunately Mr. Siegel doesn’t realize that the Nazi party was left wing and not “alt-right” at all.

ANY party that declares itself to be Socialist and has the ideology that the people have NO rights except those which the party deigns to allow, that suppression and censorship of any opposing views is allowed, that children actually belong to the nation/government, that corporations and businesses are allowed to remain in business if they support the party and provide financial, technical, and/or supply support, and that all religion is secondary to the “party” IS NOT ALT-RIGHT, or even conservative!

In fact, much of the ideology of the Nazi party can be found in the ideology of the Democrat Party today!