The Year Everything Changed—Continued

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

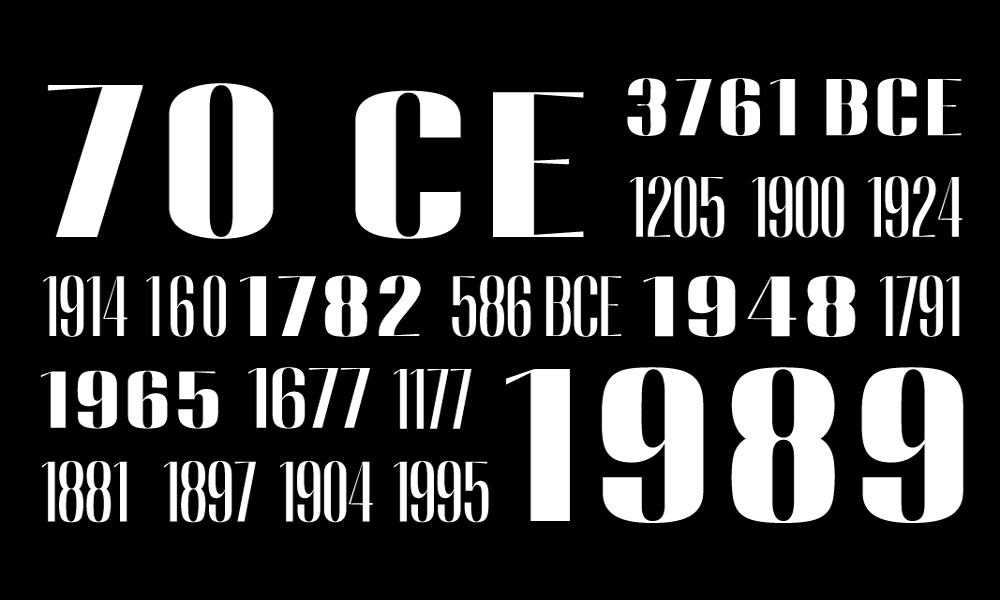

When we interviewed a group of thinkers on the years that altered human history, we were floored by their thoughtful responses. While we had to condense their answers for the print issue, we have curated additional selections from their interviews, which we are so pleased to publish here.

To view the original symposium, click here.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1492

ORI SOLTES

Continued from the original symposium.

A second-year would be the year 1492. It is, of course, the year when Columbus set sail, which put in motion an extraordinary revolution as far as European thinking about the physical world. And it is also the year when the Jews were expelled from Spain. In fact, the expulsion happened at midnight of the day that Columbus left.

This not only creates a significant new diaspora from within the Jewish diaspora, with ramifications for Jews in terms of settling in other parts of the Muslim world, and other parts of the Christian world, but also because of what doesn’t happen in 1492, which is that the institution of the Inquisition does not disappear, even with the disappearance of Jews from Spain, and a few years later from Portugal. That means that there continues to be a slow but steady flow out of the Iberian peninsula over the next generations of Jews that will ultimately have repercussions down the road in the 17th century, when one of those Jews from one of those families, a guy by the name of Spinoza, one of the creators of modern Western thought, will end up in Amsterdam.But at almost exactly the same time, the first Jewish community that had fled Recife, Brazil, ends up in New Amsterdam, creating the first substantive Jewish community there, and also what will emerge over the centuries as the most important Jewish community on the planet—the American Jewish community. So the ramifications of 1492, if one looks at a ripple effect, both with respect to the Jewish world and to the world at large, are pretty profound.

Ori Soltes is Professor of the Teaching of Jewish Civilization at the Center for Jewish Civilization at Georgetown University.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1506

RICHARD ZIMLER

Continued from the original symposium.

I discovered the Lisbon Massacre in 1990, while researching daily life in Portugal in the 16th century, but when I asked my Portuguese friends what they knew about tragic event, they all replied, “What massacre? What are you talking about?” I soon discovered that the pogrom wasn’t mentioned in schoolbooks or history texts. It had been erased from memory.

And so I decided to make the massacre the background for the novel I was then planning about a Jewish manuscript illuminator living in Lisbon. The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon—published originally in 1998—ended up telling the story of Berekiah Zarco, a studious young New Christian who survives the pogrom only to discover that his beloved uncle has been murdered in the family cellar. While beset by grief, he decides to try to track down the killer. But as a kabbalist interested in the symbolic significance of events, he grows far more interested in what his uncle’s murder and the pogrom mean for his family, the Jews, all of humanity and even for God. Berekiah offers the reader his own interpretation of the three days of violence on the last page of the novel and his surprising conclusions—referencing the possibility of future similar massacres—give the narrative chilling significance.

Richard Zimler lives in Portugal, and is the author of the 1998 bestseller, The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon. His latest novel is The Gospel According to Lazarus.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1897

ALLAN NADLER

Continued from the original symposium.

Finally, in North America, there appeared that same year the inaugural issue of the Forverts, the Yiddish Daily Forward, which quickly grew to have the largest and longest-lasting circulation, as well as the widest influence, of any diaspora paper in Jewish history. Its founder, Ab (Abraham) Cahan, harbored no illusions that Yiddish would remain the lingua franca of American Jewry, so he brilliantly shaped a newspaper that made the news available every morning to hundreds of thousands of Yiddish speakers and featured columns clearly designed to help those immigrants adapt to, and thus prosper in, the Goldeneh Medineh (The Golden Land—America). The Forverts was critically important in the establishment of a large, stable and flourishing Jewish community in America that would consist largely of the millions of descendants of its faithful Yiddish readers.

Allan Nadler is a rabbi, author and professor emeritus of religious studies, and former director of the Jewish studies program at Drew University.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1905

BRIAN GREENE

Continued from the original symposium.

I like to think of these kinds of questions specifically as transcending the arbitrary divides of whether one has one religious affiliation or another. I do, however, feel a connection to Einstein that in part does rely on the fact that we have a shared heritage. So I feel a shared heritage and a shared perspective, but like Einstein I look at religion as something that speaks to the inner sense of harmony, the inner sense of searching, the inner search for our own place in the cosmic whole.

Brian Greene, a professor at Columbia University, is an American theoretical physicist, mathematician and string theorist.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1948

JUDEA PEARL

Continued from the original symposium.

Writing these recollections makes me realize that I, and my 1948 generation, are becoming an endangered species. Like Holocaust survivors, our number declines by the day, and there will soon be very few of us left to tell our stories. Whereas the Holocaust story resonates in hundreds of museums and memorials across the U.S., none is dedicated to the story of Jewish revival—Israel—and how it came into being in the years 1917 to 1948. For some Jewish youngsters, and to most non-Jewish youngsters, a visit to a Holocaust museum is their only exposure to Jewish history, and that exposure skips over the story of Jewish redemption. We must therefore insist on having each and every Holocaust museum expanded with a “From the Ashes” exhibit to empower us and our grandchildren with the most life-sustaining chapter in our collective psyche.

Judea Pearl is professor emeritus of computer science and statistics and director of the Cognitive Systems Laboratory at UCLA.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1968 & 1989

ROBERT SIEGEL

Continued from the original symposium.

In 1968, the Columbia University campus erupted in massive protests. It was one of those rare moments when all the normal rules and expectations were upended. A few weeks later, France also erupted, with protests led by workers, but university students as well. There were also student protests in Mexico City that year, around the Olympics, and in Poland, a university protest against censorship of a play became national. There was a sense that somehow the old order had played out and we were into something new. The feelings I had that year came back to me in Poland in 1981, when I remember an important Solidarity figure telling my producer, “Tomorrow I could be in the Cabinet, or in prison.”

I’ve always placed a lot of store in generations. During the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia, the reformist prime minister, Alexander Dubcek, had a second-in-command named Zdenek Mlynar, who had been close friends with Mikhail Gorbachev at Moscow University. They were part of a generation of communists who were young when Stalin died, when there was great optimism. That age group came to power in Czechoslovakia in 1968. It took Gorbachev 20 years longer to arrive at power in Moscow, but he was part of the same generation. So 1968 and 1989 are linked.

Of course, 1968 was also a time of tremendous Jewish self-confidence after the Six-Day War. It was intoxicating. Probably for my generation that meant there was no excuse to be passive. Jews were prominent in the New Left: Adam Michnik and Aleksander Smolar in Poland, Daniel Cohn-Bendit in France and Mark Rudd at Columbia—all Jewish to some degree—and Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies at the 1968 Democratic convention, which was a glimpse of chaos and instability. The New Left responded to the bankruptcy of the Old Left, for whom the invasion of Czechoslovakia was a traumatic event, the end of the idea of socialism with a human face.

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, it was like that feeling in 1968: The people in charge really were not in charge, and we didn’t know what was going to happen, only that it was going to be very different. We thought we were seeing the beginning of a new order for which we could just build on postwar institutions. We had no idea that there would be communists who turned into capitalists on a dime and made off with everything of value in some of these countries. We couldn’t foresee the new relationship, or some might say the restored relationship, between Jews and Central Europe, which led to utterly unthinkable things like Berlin becoming a hotspot of Israeli expat society.

For people who thought nationalism and militant-racist-tinged nationalism had been stamped out and defeated in World War II, it’s been shocking to see those ideas find a new footing. The great importance of these landmark years is that you don’t know what the outcome is going to be. It’s a remarkable experience of covering a big story, that, in hindsight, you experience the arc of it, with a beginning, middle and end, but in the thick of it, you have no idea.

Robert Siegel, a special literary correspondent for Moment, was host of NPR’s All Things Considered.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1989

YOSSI KLEIN HALEVI

Continued from the original symposium.

For me personally, living that year in Europe, seeing the collapse of Communism up close, experiencing a sense of shared joy with Poles, with Germans, was deeply disorienting for me—in a positive way. I grew up in a survivor family and the thought of experiencing joy with Germany and Poland would have been inconceivable for me. But Poland and Germany helped defeat the Soviet Union, and their victory was also ours. I was privileged to be there, to report about it. And to get a glimpse of what a redeemed world could look like. To have experienced redemption in Berlin of all places.

Yossi Klein Halevi is an American-born Israeli author and journalist.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1989

DANIEL LIBESKIND

Continued from the original symposium.

A second date is 1989, where in Berlin, the wall was coming down. But I think more importantly the suppression of the revolt at Tiananmen Square, which at that time seemed to be just a minor blip on the optimistic horizon of history. But looking backwards, we can certainly see that the suppression of the Chinese people was the event that we experience today, which is not just the rise of China, but the rise of worlds of totalitarian and authoritarianism, with China as the paradigmatic model of success. So to me that’s the second date.

Daniel Libeskind is a Polish-American architect, artist, professor and urban designer. His projects include the Jewish Museum in Berlin, Germany.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Various

RACHEL ADLER

Continued from the original symposium.

I also have a kind of third category, when we are forced to encounter times of plague, disastrous social crises for which we had forgotten that there are precedents—then our world changes. In these cases, the world has not changed in an unprecedented way, but it has reverted to a condition that we had forgotten, such as coping with a plague. Even in those situations, rather than asking “how does this plague or crisis change us,” we might more usefully ask, “how can people change the world while isolating because of a plague disaster?” If we’re fortunate enough to have some free time, we can choose to innovate or rethink in ways that benefit others as well. And we might just change the world.

Rachel Adler is the Rabbi David Ellenson Professor of Jewish Religious Thought at the Los Angeles campus of Hebrew Union College.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________