Some years we look back on and savor. Other years, like this one—well, we’d just as soon have been elsewhere (or elsewhen), for a lot of it. And those are the years when we really, really need our books.

Looking back at the fiction that I spent the most time with in 2023—those Moment reviewed, those featured in our Ten Best Books video and those that slipped by without reviews—I can’t help noticing the steady lure of the stories that took me the farthest away. It’s not escapism, exactly, since many of the times and places to which the best books of 2023 transport the reader are even darker than our own. In nonfiction, you expect this. History, biography, memoir are all staples of Jewish nonfiction; and history, it’s been widely noted, is no fun when it happens to you personally. But in the year’s fiction, too, I’ve fallen in love with a couple of novels from a mini-genre that might be called very-near-future techno-dystopias, which tend to feature artificial intelligence, universal surveillance and extremely large companies.

The Jewish content in some of these novels is subtle. But if the Jewish characters wear their identities lightly, they move through plots that strikingly evoke, and embroider on, classic Jewish themes—memory and forgetting, the primacy of the written word, the infinite worth of a single human life. You might even call them midrash—imaginative commentaries on Jewish texts and ideas. Or maybe that’s far-fetched of me. But judge for yourself.

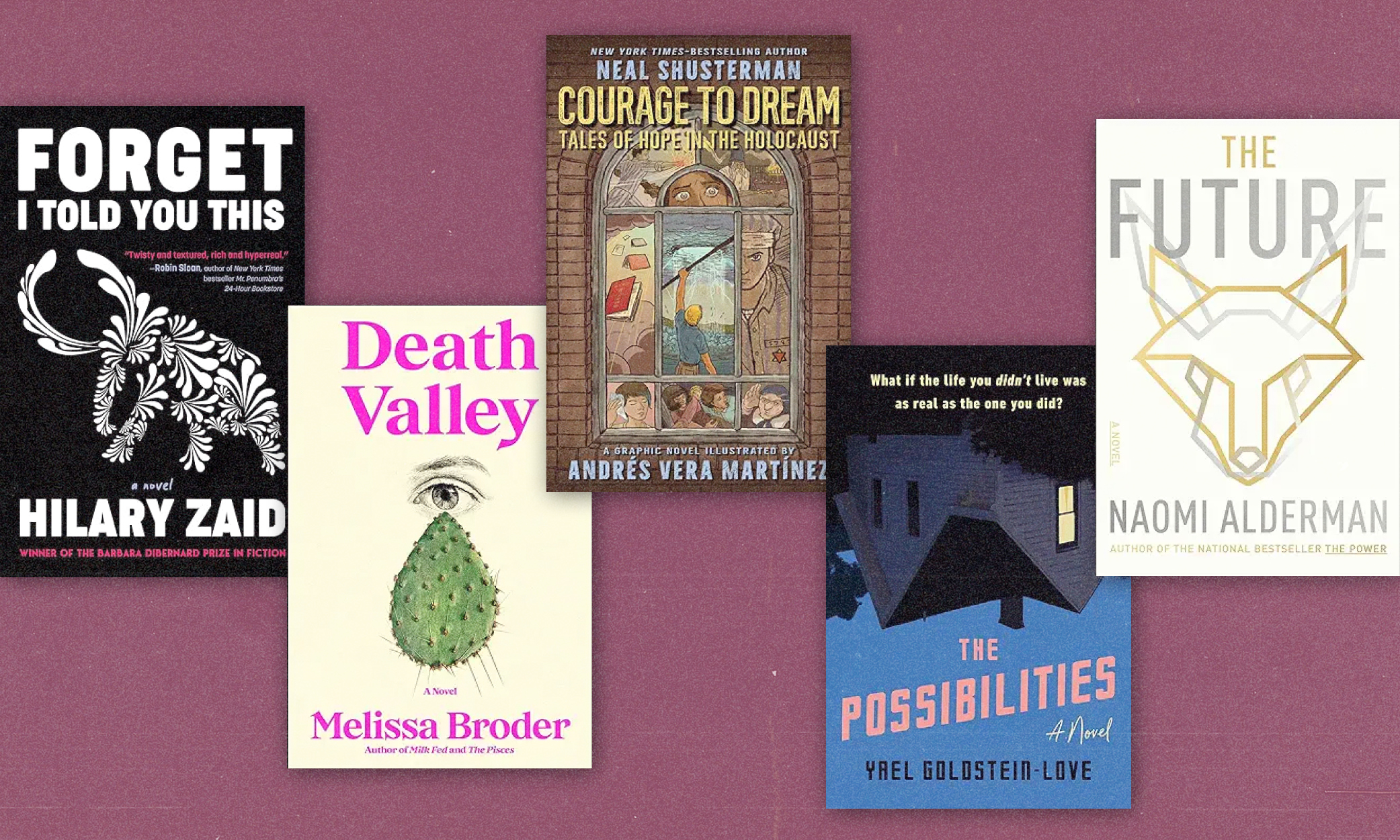

Forget I Told You This, by Hilary Zaid (University of Nebraska Press, 289 pp.), is about a scribe—a defiantly anachronistic artist of the written word who handwrites love letters for customers in a day-after-tomorrow San Francisco where “People don’t read. People don’t write.” Screens and surveillance rule all, and all decent jobs are with the mega-company Q, which owns everything and tracks everybody. A mysterious customer wants the scribe, Amy Black, to write a letter that will “make Tal forget me,” and the scribe finds herself drawn into a conspiracy to wipe the fearsome Q database—freeing the population but destroying the sole remaining record of much of world culture in the process.

Forget I Told You This, by Hilary Zaid (University of Nebraska Press, 289 pp.), is about a scribe—a defiantly anachronistic artist of the written word who handwrites love letters for customers in a day-after-tomorrow San Francisco where “People don’t read. People don’t write.” Screens and surveillance rule all, and all decent jobs are with the mega-company Q, which owns everything and tracks everybody. A mysterious customer wants the scribe, Amy Black, to write a letter that will “make Tal forget me,” and the scribe finds herself drawn into a conspiracy to wipe the fearsome Q database—freeing the population but destroying the sole remaining record of much of world culture in the process.

The book’s not about Torah, exactly—although Amy reflects that “on calfskin curled around two wooden rollers had been tattooed the history of the world”—but anyone who resonates to the sacredness of text and the fragility of memory will feel those ideas being delicately and elaborately explored. Amy’s emotional touchstone is a “dark soferet” [female scribe] she once saw working away in a Jewish museum, “murmuring over her sacred words…Because the text was more important than the scribe. That was our tradition.” Zaid’s first novel, Paper Is White, was about Holocaust historians and survivors, and in this novel, too, memory and forgetting become something absolutely central.

The Future, by Naomi Alderman (Simon and Schuster, 415 pp.), takes place in another superficially similar near-future universe: It’s still the day after tomorrow, somewhere on the West Coast, with every character capable of tracking every other one in real time. A seamless web of virtual reality enfolds the real world and cuts human beings off from nature—with the exception of those who have dealt with the situation by joining one of the numerous survivalist cults. Some of the novel’s characters are at or near the top of the tech pyramid, and the algorithms are theirs to command—up to a point. Then there’s Martha Einkorn, who’s crossed over: Her father raised her as an “old Enochite,” a member of a technology-averse forest cult, which she escaped to become personal assistant to an immature genius mogul, a sort of mash-up of Steve Jobs and Sam Bankman-Fried.

The Future, by Naomi Alderman (Simon and Schuster, 415 pp.), takes place in another superficially similar near-future universe: It’s still the day after tomorrow, somewhere on the West Coast, with every character capable of tracking every other one in real time. A seamless web of virtual reality enfolds the real world and cuts human beings off from nature—with the exception of those who have dealt with the situation by joining one of the numerous survivalist cults. Some of the novel’s characters are at or near the top of the tech pyramid, and the algorithms are theirs to command—up to a point. Then there’s Martha Einkorn, who’s crossed over: Her father raised her as an “old Enochite,” a member of a technology-averse forest cult, which she escaped to become personal assistant to an immature genius mogul, a sort of mash-up of Steve Jobs and Sam Bankman-Fried.

Martha’s father was the sect’s prophet, Enoch, and the Genesis vibe isn’t accidental; it turns out that she’s haunting the survivalist chatrooms, posting long discussions of the story of Lot, Lot’s wife and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah (to the perplexity and rage of the survivalists, who are there to talk about weapons and canned goods). The Lot story proves more relevant than expected to those who escape our world just in time—or so they think—but can’t resist looking back.

Alderman is a scary writer, best known for the novel The Power, a supercharged dystopian fable about what happens to the world (spoiler: nothing good) when young girls develop an extra organ that allows them to deliver lethal electrical shocks through touch. The Future comes across as kinder and gentler at first, but it’s up to something equally unexpected. And really, when was the last time someone gave the story of Lot (as opposed to, say, the Noah’s Ark one) serious attention as a political fable about escaping a society, or a planet, in collapse?

The Possibilities, by Yael Goldstein-Love (Random House, 291 pp.). If we’re working through a library of Jewish concepts, this novel can be read as an extended riff on the principle that to save (or extinguish) a single life is to save (or extinguish) an entire world. Or universe. It’s also an entry in the increasingly popular infinite-parallel-worlds genre, not to mention a nice addition to the shelf of interesting and serious recent novels that take on the surreal intensity of motherhood in its early stages.

The Possibilities, by Yael Goldstein-Love (Random House, 291 pp.). If we’re working through a library of Jewish concepts, this novel can be read as an extended riff on the principle that to save (or extinguish) a single life is to save (or extinguish) an entire world. Or universe. It’s also an entry in the increasingly popular infinite-parallel-worlds genre, not to mention a nice addition to the shelf of interesting and serious recent novels that take on the surreal intensity of motherhood in its early stages.

The protagonist, Hannah Bennett, battles such overwhelming anxiety in caring for her eight-month-old son Jack—whom she almost lost in a difficult birth—that she periodically finds she’s crossed over into an alternate reality where he didn’t make it. Soon she’s “riding the possibilities,” struggling to keep the infinity of universes where something went wrong with Jack—by far the majority, it seems—from leaking back into the one where she’s managed to keep him safe. I don’t know that the physics make much sense, but as a way of conveying the emotional quality of those early months of parenthood, the construct is incredibly effective. It’s years since I had a baby that age, but my copy of this book has split its spine from rereading.

Death Valley, by Melissa Broder (Scribner, 232 pp.). Another surrealist take on parenting and being parented—this time focused on fatherhood. Broder contributed one of the best entries to the surrealist-Jewish-mothering genre with the 2021 Milk Fed, in which a calorie-counting nonobservant Jewish 24-year-old named Rachel becomes obsessed with a female Orthodox colleague who feeds her a lot more than just calories.

Death Valley, by Melissa Broder (Scribner, 232 pp.). Another surrealist take on parenting and being parented—this time focused on fatherhood. Broder contributed one of the best entries to the surrealist-Jewish-mothering genre with the 2021 Milk Fed, in which a calorie-counting nonobservant Jewish 24-year-old named Rachel becomes obsessed with a female Orthodox colleague who feeds her a lot more than just calories.

In this new novel, the narrator’s flawed but loving father is in the ICU with a broken neck and in a stubborn coma, and she has fled to a Best Western in the desert to dodge her deadlines (“One thing about a tragic situation is having an excuse to say no to everything”) and, when all else fails, to confront her mortality and the mortality of the species generally. She’s not the first to conclude that, all things considered, it’s a pretty heavy lift. Milk Fed’s spiritual vocabulary, though weird, was recognizably Jewish, but this narrator, who talks to the deity incessantly from the first page, has fewer landmarks: “Since I don’t turn to god very often, I feel self-conscious when I do. I’m not sure what I’m allowed to ask for, and I’m worried that I shouldn’t want the things I want.” But the blank slate makes the journey not just original and hilarious but ultimately quite powerful. Who says God (or god) can’t be found inside a giant cactus that no one else can see?

The Courage to Dream: Tales of Hope from the Holocaust, by Neal Shusterman; illustrated by Andres Vera Martinez (Scholastic, 245 pp.) This graphic novel won’t suit everyone—you have to be comfortable with the idea of mixing fantasy and fairy tales with Holocaust history to produce happy endings where there were none. And aiming such hybrid stories at younger readers, as this volume does, raises further issues.

The Courage to Dream: Tales of Hope from the Holocaust, by Neal Shusterman; illustrated by Andres Vera Martinez (Scholastic, 245 pp.) This graphic novel won’t suit everyone—you have to be comfortable with the idea of mixing fantasy and fairy tales with Holocaust history to produce happy endings where there were none. And aiming such hybrid stories at younger readers, as this volume does, raises further issues.

But Shusterman has an immense following and a sure narrative hand. The illustrations keep pace. In one of these tales, a golem arises in Auschwitz and helps stage an escape before crumbling to dust; in another, a group of resistance fighters in an Eastern European forest encounter first the legendary fools of Chelm and then the terrifying Baba Yaga, who, though she’s wandered in from another culture’s mythology, decides to lend a hand and proves surprisingly supportive in fending off Nazis. Despite my queasiness, the artistry of the stories, together with Shusterman’s insistence that his purpose is to encourage hope in dark times, not falsify history, makes for a gripping read. He writes movingly in an epilogue about the need to explore not just despair but hope, to ponder alternative realities and make people consider how things could have gone.

Shusterman isn’t the first artist, of course, to be tempted by the desire to apply magic realism to the Holocaust. He’s not even the first to use a golem—Alice Hoffman did it in The World That We Knew in 2018. As the secular year wanes and the days start to lengthen, maybe a little fantasy cautiously mixed into the darkness is acceptable—especially with so much sadness to contend with. Happy New Year!

*Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

Since you mention the holocaust, I wonder if you have come across Chava Goldfarb’s trilogy, The Tree of Life. Hands down the best writing and storytelling I have had the “pleasure” to read about the most dreadful part of Jewish history. As writerxand avid reader, I cannot recommend these 3 books enough. Originally written in Yiddish and translated by Rosenfarb’s daughter.