This story is the first-place winner of the 2005 Moment Magazine-Karma Foundation Short Fiction Contest. Founded in 2000, the contest was created to recognize authors of Jewish short fiction. The 2005 stories were judged by Judy Budnitz, author of If I Told You Once and Nice Big American Baby. Moment Magazine and the Karma Foundation are grateful to Budnitz and to all of the writers who took the time to submit their stories. Visit momentmag.com/fiction to learn how to submit a story to the contest.

To see this piece in its original context, click here.

Whenever Harry told his story, whether sitting in his moss-green winged-back chair, or standing near someone’s barbeque grill, or on a walk through the gardens at Cranbrook, he began with the old-fashioned shoes. His father, Joe, had found them in the cave-like basement of the building where they ran the family shoe business. Those shoes were a sight. Three pairs of high lace-up pointy-toed boots in black and brown, mini-torture chambers, so small and narrow in the foot and ankle that it was hard to imagine anyone who could fit into them without severe structural damage.

Ilo, Harry’s sister, placed the shoes in the big plate-glass front window, on a wooden table below the dark-green arcing letters that said J. Goldberg Wholesale Shoes. She dusted them once a week and polished them once a year, with brushes and buffing cloths, and fussed with the arrangement, adding seasonal accessories, as if she were a window decorator at JL Hudson, Detroit’s big department store. Harry said nothing about it, as he said nothing about much of what Ilo did in their long history of brother-sister silence. But he did like having the shoes there, as they seemed to elevate their business, along with the concept of shoe, into the sweep of history. The odd part about having a front-window display was that, being in the whole sale trade, Harry and Ilo weren’t looking to advertise. And they didn’t especially want to attract attention from the neighborhood.

Oh, the neighborhood. The building was on Grand River, a broad angled street that ran through Detroit as if drawn with a ruler. The cross street, just to the east, was Joy Road. Now there was a misnomer. Joy Road was all concrete and brick, broken glass and traffic, grown men with nothing to do during the day, and buses belching clouds of black smoke as they roared past the metal-grated building faces. Goldberg’s didn’t have a metal grate in front, though. Harry wasn’t going that far.

When Harry talked about that neighborhood, the sisters-in-law and aunts, with their stiff beauty-parlor bouffants and manicures, held their faces and said schwarze this and schwarze that. Same for the big-bellied men with their ruby pinkie rings. But in Harry’s house, no one used that word—not Harry nor his wife, Ruth, nor his daughters, Joanna and Lisa.

By now, whoever Harry was talking to wanted him to get on with the story, especially if they were Detroiters, or Jewish Detroiters, who knew about those neighborhoods, the Jewish-owned businesses in the scwharze neighborhoods, and even a little bit about what happened to Harry all those years ago: 1967. “We get the picture, Harry,” they’d say, moving out of range of the barbeque smoke.

So Harry got on with it. Every day, he said, after Joe retired and moved to Florida, he drove over to get Ilo, and together they rode down to the office. She worked until noon, keeping the books, and then took the bus home. “How could you let your sister work in a place like that?” people asked. “I brought my daughters there, too,” he said. “We had locks, and the bars in the back, and the burglar alarm. We were okay.”

“But I hated that drive,” Harry always said, running his knuckle over the mustache that, combined with his dark wavy hair and dark eyes, could make a person think of Xavier Cugat, of south of the border. Not only the traffic he hated but the weather—the sun blasting down in the summer, his back stuck to the seat. Then the storms that blew up in the winter—treacherous, slippery inching along. And something beyond that: Every morning, he pulled away from his freshly painted three-bedroom colonial on a treelined Detroit street where children played in grassy front yards. And where did he land? A place where children played in broken-glass alleyways, or behind barred windows in apartments that were old beyond old, layer on layer of resignation and demise. And something else he hated—that he wouldn’t tell about: As he drove, he tried to ignore Ilo there beside him, because if she was there, he couldn’t pretend even to himself that his life was anything other than what it was.

At this point, Harry might tell about his tenant, Curtis, who lived with his family upstairs from the business—a big man who’d learned how to scale himself back so he didn’t seem dangerous. The eyeglasses helped, Harry said, the way they never sat right on his face, the clean handkerchief in the back pocket, the blue workman pants and the clean white T-shirt. Mostly, his shy smile, looking down, as if he’d gotten used to holding back his thoughts.

The upstairs apartment wasn’t as bad as some, Harry said. He was a decent landlord, keeping the place up—spraying for roaches, venting the radiators, making sure the water drained off the flat roof. “Tell about going in the middle of the night to fix the boiler,” Ruth might say at this point. “Tell about the shoes you gave the children.” But Harry didn’t like to sound as if he was bragging, so he didn’t tell. He said to Ruth, “Are you going to tell the story, or am I?” And she said, “Sorry.” So he began to tell.

It was a Friday in July, Harry said, a hot Detroit Friday, air too thick to breathe, even that early in the morning, and the phone ringing as he opened the locks on the back door of the business and flipped the switch on the burglar alarm. So many small impressions had stayed with him from that day: Ilo going to the high bookkeeper’s desk to answer the phone, and reaching for the pad of pink order forms. The new summer dress she wore, a sleeveless shirtwaist, in some light, crisp material. Yellow. Like a big daffodil, he thought, not especially flattering. Him watching over her shoulder as she took the big order. Harry said he’d always remember that day because it had felt so special to get the unexpected order, such a big one, and from Hudson’s. In those days, Harry liked to say, you weren’t small potatoes if you were selling to Hudson’s. Then him, going up the wooden back stairs to get Curtis to help him. Ilo calling after him to talk to Curtis about when was he going to pay the July rent. Then the two men, working side by side in the big back room with the long wooden tables and the tall barred windows.

They counted boxes, piled them up, pulled rope from big reels, tied stacks, checked items off on the pink order forms. Women’s tennis; neoprene work boots. Baby’s shoes. Harry remembered that he and Curtis kibitzed, about their lives, about their kids. And perhaps for Harry, this next part was bragging, but he always told it anyway, painting the picture as best he could, sometimes imitating Curtis’s deep voice, with the country in it.

“Mr. G,” Curtis had said. “You know my son Alvin.” And he put a little question in his voice, but not a real question.

Of course Harry knew Alvin. Alvin, with his head so finely sculpted it might be a mannequin head, his flat smudged eyebrows, as if thumbed on with finger paint. Alvin, with the heavy-lidded slit-eyes and unsmiling lips that said he’d already seen enough to know how much was wrong. Harry knew Alvin. Alvin was the one with the beautiful voice that could go to falsetto. And Alvin was the one who had rigged a phone line in the basement a few years back, working off Harry’s business line. More than one person, including Ilo, had called Harry nuts for letting it go with a shrug.

“Well,” Curtis said, “the other day Alvin asked me, ‘Why you friends with that white man?’ Talking about you, you know.”

Harry always paused his story a couple beats here and rested his hand on his chest before telling how Curtis answered, saying, “That’s no white man. That’s Harry Goldberg.”

No matter how many times Harry repeated this over the years, he always shook his head at this point—confusion, disbelief, who knew what? A little pain around the eyes, a little pride in the lift of the chin. Depended, maybe, on whom he was telling. “And I said to him, ‘Thanks, Curtis. I’ll take it as a compliment'”

When he told about this conversation, Harry liked to say that Alvin was a different kind of person than his father, more impatient and more hopeless and more angry. And why not? Harry used to say. One more year of high school and then what? Not like Harry’s kids— Lisa in college, and Joanna on her way there.

Sometimes Alvin worked at Harry’s too, but Ilo didn’t like having him around. She wouldn’t open the door to him, wouldn’t even ask what he wanted. To be honest, Harry admitted to some people, Alvin didn’t always do such a good job. He was careless about sorting and stacking the sizes while he dreamed of something else—becoming a Motown star, probably, singing with the Temptations. Sometimes Alvin’s rows fell over, and then you had the domino effect, or Harry found 12s mixed in with 9s, white sneakers with blue, and then he had to straighten it all out himself.

When Harry and Curtis finished packing the big Hudson’s order, around noon, Harry pulled his cash out of his pocket and handed Curtis a twenty. Then he thought again, and added a ten. Which later, Ilo said, was ridiculous for Harry to be paying Curtis when Curtis owed Harry rent money.

“A man’s time is worth something,” Harry told her, hoping to close the subject

When Harry left work that night, he saw Alvin out front, standing with some boys his age at the bus stop, dressed in bright-colored slacks and shirts. Sharp dressers. The way they leaned in toward each other, he said, they looked like they might be singing.

The way Harry liked to tell the next part was with a sigh of exasperation and a description of that Sunday morning, with Ruth and him having a late breakfast and the phone call from Ruth’s brother, Irv, in a panic, telling Ruth to turn on the television. Irv was babbling about gunshots, not far from his home, and about how it had all started at Twelfth and Clairmont. And Ruth was saying into the phone, “What? What started?” And Irv saying, “Well, you’re the only ones in the city who don’t know.”

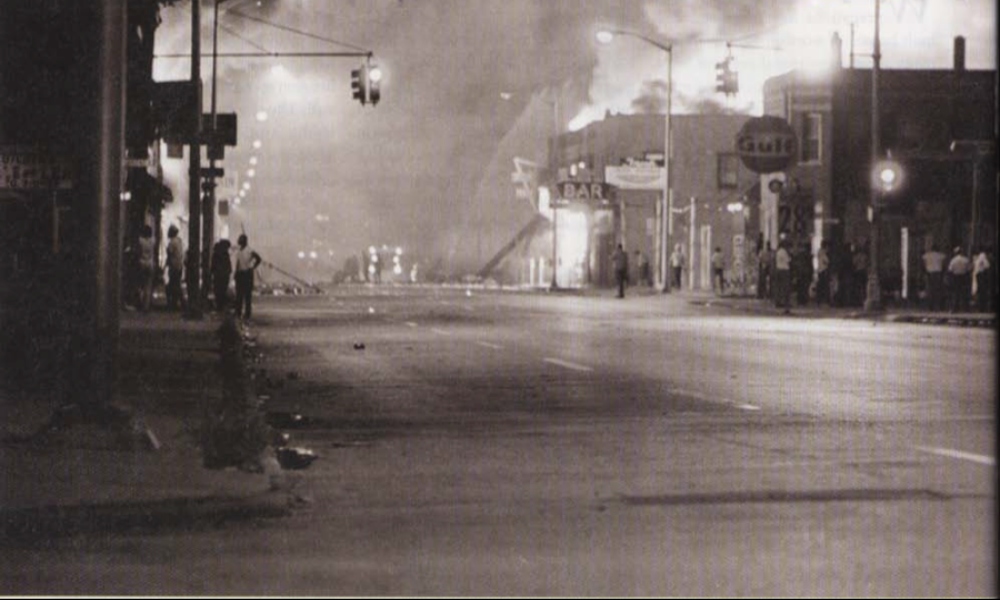

And not yet believing, Harry and Ruth tuned in, and Irv was right. They watched flames and black clouds filling the skies of Detroit. Looters slamming garbage cans into store windows, running through streets with armfuls of clothes, pushing shopping carts with loaves of bread and bottles of liquor, kitchen chairs, stereos. Harry watched for landmarks, storefronts, intersections, familiar faces. He knew the places pictured in the news reports, knew the broad swath, the sad scary slash highlighted in the TV maps.

And then he watched tanks rolling down the city’s expressways and broad boulevards. Heavily armed riot police and National Guard moving in to put down arsonists, looters, snipers—specialized tides for previously nameless, invisible Detroiters. Newscasters used domestic images—pots boiling over and pressure cookers. Officials placed blame, pointed fingers, analyzed causes.

“Causes, schmauses,” Harry always said with disgust after he described the TV images. “You could feel this thing coming a mile away.”

He told about Mayor Cavanaugh, whose televised face could barely conceal his sorrow over this end to his Model City dream, asking Detroiters to stay home until the situation was under control. “Oh, yeah,” Harry scoffed, “The rioters were going to stay home because the mayor said?”

Ruth, as Harry described her, was like a fly trapped between a screen and a storm. She paced the house, went out to check with the neighbors, who gathered and debated near the curb. She called everyone she knew, making the panicked inventory of friends and family— regretting now, even more than usual, that she’d given up smoking.

“And me?” Harry asked, “I stared at the television. Twelve square miles of our city, burning. And some of those square miles were around Grand River and Joy Road.” Sometimes Harry laughed at this point in his story, the soothing distance of time allowing for humor: “Too bad Alvin didn’t have his bootleg phone then, or I could have called.” And if he knew he was talking to a like-minded person, he might indulge in a rant, say what a waste the whole thing was. A city torn up. People killed.

“Because some colored folks were partying at a blind pig on a Saturday night,” he said, “To welcome a couple Vietnam vets home. That was such a sin?” He railed at the cops, said they couldn’t leave well enough alone. “And why not?” he demanded, even though he’d found his own answer long ago. “Because somebody at Clairmont and 12th had gotten tired of paying them off….” He almost always shook his head then, and stared into that faraway time. “The end of a city?” he asked. “For that?”

Anyway, said Harry, getting back to when he was sitting in front of the TV in his green wing-backed chair on that shattering Sunday in July. Anyway, he explained, during the late afternoon, the news showed a tank stopped on Livernois, the fancy street of shops, not a mile from Harry’s house, where Ruth and the girls sometimes shopped. Behind the tank, the TV camera panned past Alexander’s, the dress store with its front window boarded up. Harry knew about Alexander’s from Ruth—about Greta, the stunning shop owner, with her European accent and perfect complexion. About her outrageous price tags. And of course about the royal blue dress Ruth had brought home a few weeks ago—to see what he thought, because she needed something special for their niece’s wedding, and he’d said okay, if she put it on layaway. Harry called to Ruth to get off the phone and come look at the TV.

“Good grief,” Ruth said when she came into the room. She didn’t say anything about the blue dress, of course, sinking down onto a chair next to Harry’s and saying, “After all Greta went through in Europe.” And then she kept an eye on the TV while she told Harry stories she’d heard from the neighbors. One had a brother-in-law who lived a few blocks from Livernois. When the brother-in-law heard about the riots, he’d grabbed a shotgun and ran out to patrol the block. A Jew with a shotgun? Ruth muttered, incredulous. Another neighbor had heard of fires burning south of Seven Mile, across from Lou’s Deli, not far from Ilo’s house, but Ilo was okay, Ruth said. She’d just talked with her.

And so the days went, Harry explained—television, phone calls, rumors, temperature in the 90s, high humidity as far as the forecasters could see. And fear. So much fear.

This next part of the story was strange to tell, but he told it anyway. He’d start off saying this: “By Wednesday, I couldn’t stand it anymore. The sitting around, wondering. Feeling Ruth’s eyes on me. By then, I’d fixed every damn thing in the house. I think I cut the grass three times.” So he got up early, before Ruth, and left the house, quiet as he could.

The streets were practically empty—even the usually busy Outer Drive, a fine broad boulevard of graceful curves that swept through the city lined with big brick houses on large lots. As he drove, he scanned the lawns and bushes, glancing down side streets. No children running through sprinklers. No one walking the dog. No annoying lawn mower buzz. He might have been the last person on earth except for the reminder from the sirens in the distance. At Outer Drive and Livernois, a tank blocked the intersection, and a soldier in combat gear came to Harry’s car, motioned him to roll down the window.

He was young—too young for the heavy weapon, Harry liked to say. Sweat beaded on the boy’s forehead. “No cars allowed on Livernois, sir,” he said. Anyone could see, Harry said, that the boy would rather be home with a cool drink and a girlfriend than decked out like that, telling a man more than twice his age what to do.

“But I have to . . .”

Two more guards came to join the first, and Harry admitted, he’d thought about doing something irrational, stepping on it, squealing his car between the tank and the curb, running over the curb if he had to. But no. They’d only stop him farther up. And he knew the neighborhood well enough that he could find a way around, and get onto Livernois farther south. So he gestured sayonara to the baby-faced men and made a U-turn.

On the side streets, he passed through deserted neighborhoods of well-kept brick-and-stone houses. He pulled into an alley and wound his way west, south, then west again, gravel crunching beneath his tires, pink hollyhocks poking out from spaces between garages, rusty fences covered with morning glory vines.

In an alley behind the Orthodox shul on Seven Mile, a man motioned to him, the way a police officer does, directing traffic. The man was tall and thin, brown skinned and stooped, wearing glasses and a gray hat that had a high crown, like a train conductor’s hat. He wore a red and blue plaid flannel shirt, tucked in. Funny, Harry thought. A flannel shirt on such a hot day. The man guided him to a parking spot behind the synagogue.

Harry had often seen people walking to and from this shul for Sabbath—the men in their wide-brimmed black hats and the long quilted coats that looked like satin bathrobes—their wives in long skirts following behind, and then the children. Always so many children. Whenever Ruth, riding in a car on Shabbos, saw them—and felt that they might see her—she wanted to duck. She’d been raised in a family like that, Harry explained. But once she’d gotten serious about Harry, who was practically a goy, she’d pulled away from that Orthodox life, or noose, as Harry liked to call it.

“All that’s left of her old ways,” Harry liked to say, explaining her instinct to duck, “is the guilt.” But that was not true. Remnants, like the dust that accumulates in pocket seams, lay in tiny, ancient chambers of the heart. Even in Harry’s—a man who wasn’t even aware that he had pockets.

The man with the conductor’s hat came to the driver’s side window, as if he had been expecting Harry, and Harry opened the door.

“Just in time,” the man said. “They need one more for the minyan.” His face looked familiar to Harry, as did his long fingers with the smooth, curved nails, but somehow this familiarity wasn’t surprising. The man waited for Harry to get out. “It can’t have been easy to get over here,” the man in the hat said. He held the door for Harry. “The others, they live down the street.”

“How did you get here?” Harry asked as he followed the man through the back door of the shul, up the steps. It was cool inside—the cool of a place made of linoleum and cinderblock, closed up against the summer heat. And the cool made him shiver in his short-sleeved T-shirt, damp with sweat.

“Me?” the man in the conductor’s hat said. “I’ve been here since Friday. Can’t get home for a while, I guess.” Just before he opened the sanctuary door, the man handed Harry a yarmulke, and Harry put it on his head.

The room had tan walls of painted cinderblock, bathed in a cool green light from high, tinted windows, with a balcony for the women, and with the white satin-curtained holy Ark on a raised wooden platform in the middle of the main floor. Harry had been in shuls, of course, temples, synagogues—people called them different names—though mainly for weddings and bar mitzvahs, where he could almost feel comfortable, lost in the crowd. But this room had no crowd to get lost in. Only the group of bearded men, dressed in black pants and white shirts, wearing skullcaps, wrapping black leather straps around their arms and heads, and now looking at him.

Harry knew enough to recognize what they were doing with the straps—donning their tefillin—though until now, he’d only ever seen them in pictures. And speaking of pictures, he liked to say, he felt that he’d stepped onto the set of the wrong moving picture, or simply slipped through some membrane into a different world. The man with the conductor’s hat backed away, let the door close behind him, and one of the worshippers came up to Harry, his tefillin already in place.

The man carried another set of tefillin, dark coils in his open palms, and offered them to Harry, who shook his head no. Harry felt a panic of shame. But the man said he would show Harry what to do. “Okay,” Harry liked to say when he got to telling about this part of the unlikely events unraveling before him. “What choice did I have?”

So the man began. First, he pantomimed the reverent kiss for Harry, and Harry complied, lifting and kissing the two little boxes that were attached to the leather straps, then placing them back in the man’s hands. Then, the man, mumbling softly to himself—”It sounded like he was praying,” Harry said—made a noose above Harry’s elbow with the long leather strap, and placed the little leather box, two or three inches in width and height, on the inner side of Harry’s left arm. The box looked like a small wooden house, and Harry liked to say that at least he knew that the prayer was stored in there.

After the man tightened the knots, he wound the leather strap around and around Harry’s arm, spiraling down toward his hand. Harry stood awkwardly with his arms out from his body, as if he were being fitted for a suit by a tailor. Then the man left the straps hanging from his arm and motioned for Harry to lower his head. The man was short, shorter than Harry, and he had to reach to place the second little wooden box in the middle of Harry’s forehead, above his hairline.

Harry closed his eyes while the man worked, the way he did when he sat in the barber’s or dentist’s chair. He could feel the leather straps being looped around the back of his head, knotted, and left hanging down the back of his neck. When he straightened up, and opened his eyes, he felt like he had a horn growing out of his head, or like he wore a little clown hat at a jaunty angle. And the man who was outfitting him had one too, as if they were members of the same tribe or the same traveling circus.

Under normal circumstances, he liked to say, he would have felt silly, perhaps been tempted to make a joke. But these were clearly not normal circumstances, and he felt cared for, groomed. And for the first time since he’d heard the news of the riots, he wasn’t fretting about his business, his building, his inventory.

The man nodded encouragingly at Harry, as a tailor or a barber might, once he was pleased with his work, and went back to Harry’s arm, winding the hand strap three times around Harry’s middle finger. The man touched Harry’s arms, as if to tell him to relax them, which Harry did, and he felt the little box high up on the inside of his arm, pressed into his side. Finally, the man draped a prayer shawl over Harry’s shoulders and moved away to get Harry a prayer book and to find his own, stored in a blue velvet bag.

Then the other men, who Harry now saw had been waiting for him, pulled their prayer shawls up on their heads, and Harry did the same. But the man who had been helping him hurried back over to Harry, to help him arrange the prayer shawl so it would not touch the wooden box but rest on Harry’s head behind it.

The men opened their books and began to read and chant—mumbling and rocking, occasionally bending at the knee and bowing forward, in the way Harry remembered from his childhood, when he’d gone to shul with his grandmother. Harry knew the smell of the musty pages in the old black book with the frayed cloth bindings. And he knew the look of the dancing Hebrew letters, though he couldn’t read them. The rhythms of the chanting voices were familiar, too, beyond any familiarity he could describe, as had been the face of the man in the conductor’s hat who’d brought him here. Occasionally, one voice rose above the others, an outburst of sorrow or passion perhaps.

Although he didn’t know the prayers, he began to whisper to himself. At first, he liked to say when he told the story, he wasn’t saying words, just something like budda-budda-budda-budda, so he’d look like he was participating, helping these men give their prayers the proper weight. But soon words formed: He hoped the best for his city, for Curtis and his family, for Greta. He sent a blessing to the tragic-faced mayor. And he wished—a wish not a prayer—moving in and out of words, for the trouble to pass over, for rifts to be mended, lives to find purpose, and sweet normalcy to be restored.

He admired the spiral of the leather strap on his arm, like a sacred vein. He felt the steady pressure of the prayer box against his side, like a reminder to his heart. He let the prayer shawl fall forward around his face and shoulders, and he withdrew into it, a private tent, gradually discovering a place that felt like certainty: that if his business was burning, right then, he would manage.

All these years, he thought, the business had been good to him and his family. But now, he saw, it wasn’t good for him. What kind of person might he be if he worked in a modern office building, with meetings, colleagues—he loved the sound of that word—who stopped in to talk about movies and politics? What if he hadn’t had the burden of a broken boiler, a leaking roof, in a bad neighborhood in the middle of the night?

Albatross, shackles, prison, dungeon. A man must be made for something more than this. He knew then that he did want it to burn. And he imagined his whole lousy shoe box of shoes blowing sky high, burning with ugly black smoke—even the old-fashioned boots in the window.

“And then,” he said, “I noticed that the other men had stopped praying, and they were unwinding their straps.”

With some audiences, he made a joke here, painting himself as the pious fool, stumbling out of the shul with a stupid grin “like I didn’t know what hit me.” But with others, usually if the listener was a woman, especially later, after Ruth had died and he was looking, perhaps, for a new companion, he let this part of the story end there, with the men unwinding and kissing their tefillin straps and prayer boxes, like amulets.

From here, Harry skipped to Sunday afternoon, a full week after the riots had broken out, when Mayor Cavanaugh had given the go-ahead, and people were facing the return to their normal routines. But his listener sometimes stopped him in mid-sentence: “Didn’t you tell Ruth about the shul?” they’d ask. “Oh, that,” Harry might say. “Yes, of course I told her.” And, he explained, she had listened, amazed that someone as goyish as him had stumbled into an Orthodox sanctuary in the midst of a burning city. And she was mad, that he had snuck out that morning without telling her what he’d planned, that he’d thought he could get through the blockades.

“For what?” she’d said. “What did you think you were going to accomplish, Mr. Big Shot?” But she’d had so many other things on her mind then, he said. She was worried about what path their lives would take next—both of them in their 50s, one daughter in college and another two years away. She was scared, too, about him going back to his building. “Take Irv with you,” she said, “or one of the neighbors.” But he said no, he would go alone.

On Monday morning, then, he got up at six, his regular time. He dressed for business—his gray suit, a white shirt, and his narrow navy blue tie. An odd choice, maybe, he said, on a day like this, but so be it. “Maybe,” he said as a joke, “I was thinking about my last outing.” And when his audience remembered what his last outing had been, he said, “Didn’t want to be caught underdressed twice.”

When he got downstairs for breakfast, Ruth was in the kitchen, cleaning out drawers and cabinets. Spice jars and coupons, carryout menus and extension cords were arrayed on the counters. He could see right away that she was sulking, Harry said, that she was going to give him the cold treatment. But when he finished his toast and orange juice, which she had set before him as if he were an annoying customer in a diner, and he got up to go, she gave up the act—kissed him, hands flat on his chest, told him to be careful, call as soon as he could, though they both knew the phone might not be working, might not even exist.

Outside, the morning was quiet. And the traffic on Outer Drive was light. The sun was low in the sky, peeking through the thick summer greenery. A gentle breeze stirred the leaves and cooled the air, but the humidity wasn’t kidding, and the sun was on its way up. By noon, the steering wheel would be too hot to touch.

When he turned onto Livernois, he found the barricades removed. Two National Guardsmen with rifles stood in front of Alexander’s. The rising summer sun reflected off the glass shards under their feet. He’d seen it on the television again and again, he said; now he was seeing it in person, but it didn’t seem any more real.

Driving south on Livernois, toward downtown, Harry passed through a residential area, where everything looked normal again. The traffic picked up, as others joined him in the return to routine. Harry loosened his grip on the steering wheel, relaxed into the seat, wiped his brow with his white handkerchief, rolled the window down a notch.

Five Mile Road was the dividing line. There, almost all storefronts were boarded up, and National Guard marched on both sides of the street, two by two. Traffic became sparse again. Harry smelled smoke, the stink of burning rubber. And then a stretch of buildings, no more than smoldering ruins, cloaked in the hazy summer light.

He turned onto Grand River, littered with rags, bricks, and bottles. Papers flew everywhere past soot-blackened storefronts, empty shells. What he couldn’t get over was that so little time had passed since he’d been here. And yet, he could barely remember which buildings and businesses had lined these streets. How unobservant he had been! In the uncountable times he’d driven past, he hadn’t realized that any of this mattered.

And finally, past Joy Road, there was his building. Standing. One of the few on the block. And, more amazing, the big front window unbroken. But, he said, and he said this hesitantly, pausing between words, something white was splashed on the window, something he couldn’t make out from the car.

He parked beyond the bus stop, in a stretch where the street looked clearer of debris. And he took a breath, two, after he turned off the engine. Not certain why, perhaps just to have something in his hand, he took a screwdriver from the glove compartment and got out. Glass crunched beneath his feet as he walked toward his store. “You know the feeling,” he sometimes said, “that people are watching but you don’t know where from?”

As he got closer, he could read the thick splash-dash letters on the window, paint drips frozen in descending paths: “Soul brother.”

“Honestly,” he liked to say, “I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.” He thought of so many things at once: the Passover blood on the doorposts of Jews in ancient Egypt, and a joke his cousin Arnie had once made—that he should call his store Sole Brother. And, of course, what Curtis had told him about Alvin. “That’s no white man.”

And then there was Curtis, coming out to meet him. And Harry put the screwdriver into his pants pocket and reached to take Curtis’s hand, but Curtis did not reach back. And Harry said how much he had worried about Curtis and his family and the business, how hard it had been not knowing what was going on. But then Harry felt ashamed of saying that anything had been hard for him compared with Curtis. And then the two men squinted into the hot July sun, which flashed off the lenses in Curtis’s glasses, and neither seemed to know what to say. This was maybe the hardest part of the story to tell because back then, Harry hadn’t known who to worry about more—himself or Curtis. And in the retelling, he didn’t know what he wanted his listeners to think of him, or what he thought of himself, even what the sign on the window meant. It was all so god-damned crazy. But he did want to finish the story. So he told about the conversation with Curtis—in which he asked first about the sign, about how it got there.

And Curtis said, “My boy. He found the paint in the basement.”

“Ah,” Harry said. The wise and crafty Alvin. And then Curtis said that it didn’t look too good around there, and Harry agreed that, no, it did not.

And then Curtis asked what was Harry planning to do with the building. And Harry told him he didn’t know, because he really didn’t. How could anyone know anything then? But, Harry said when he told this story, they were not in the same boat, and they both knew that. So Harry said, “Sorry, Curtis. So sorry about all of this—for you and your family.” And Harry thought that Curtis accepted the apology, for what it was worth, and then Harry said that he needed to go in to look around, and Curtis said okay.

“I unlocked the door,” Harry said, looking again at the message splashed in white across the window. It cast a shadow over the old-fashioned shoes, standing in their silent semicircle on the wooden table, as Ilo had left them.

“I went in,” Harry said, “closed the door behind me, sat at my desk, and stared at the walls, the file cabinets, the locked safe. Everything, exactly as I had left it.” He got up, pushed back his chair, walked through the building, up one aisle and down the next, weaving his way between the gray shelving that reached to the ceiling. And there they all were—all the shoes in their boxes. Stacked by size, brand, color. Everything, in their straight and sturdy rows. His inventory, his albatross. Sevens, seven-and-a-halfs, eights, eight-and-a-halfs, nines. The sizes stamped on the boxes. It was like dreaming. So many waking dreams lately.

“And where was my minyan when I needed them?” said Harry at this point, as a joke, to lighten the mood.

But that wasn’t all, he said, not quite having reached the end of his story. Ilo, he explained, refused to return to the office. She said he was crazy to keep going there. Did he think that sign on the window was some magic shield? Did he think it meant that everyone loved him so much? Well, just because he was crazy, it didn’t mean she had to be.

Still, in the days that followed, crazy though it might have been, he kept to his routine—driving back and forth on his regular schedule, phoning customers and vendors, toting up his assets, sometimes simply wandering the aisles, or sitting in his office chair, tapping a pencil on his desk blotter.

Once, he sat at the top of the narrow basement stairs, looking down into the darkness. Once, he considered washing the white letters off his front window. He brought rags from home, a wooden step ladder, razor blades in case he needed to scrape. But when he pulled up in front of his building and opened the trunk to get the things he had brought, he knew he wouldn’t be able to do it—stand on the street, engaged in a task like that.

Not surprisingly, and he called this his “understatement of the year,” business was not good. Many of his retail customers, located in neighborhoods that the riots had decimated, were gone. And here, perhaps the punch line he’d been working toward the whole time: While Harry sat in his silent office, hoping the phone would ring, those Detroiters who had actually lost their businesses were cashing in their insurance claims.

“And me?” Harry continued. “The city eventually bought my building for a dollar—a symbolic thing, to make it legal. And I moved on. ‘Ready or not,’ as they say.”

“Tell about working nights at the Coca-Cola plant,” Joanna said. It was July, and they sat in the suburban home Harry and Ruth had moved to after the riots. Joanna was beside Harry at the kitchen table, which was arrayed with bowls of blueberries and peaches, chunks of cool watermelon. Ilo and her husband were there, and the cousins, in from New York and California for a family wedding.

“Your mother hated it,” Harry replied. He still had the mustache, though it was gray now. “She’d be up half the night worrying. ‘A Jew at a Coca-Cola plant?’ she’d say.”

Ilo spooned blueberries into a small china bowl and said, “He would have been better off if the building had burned.”

“You don’t know that,” Harry said, annoyed with her for acting as if she were the first person to ever have this thought.

“Tell about the next job, then, at that appliance store,” Lisa said, “where you came back from vacation and found a younger man sitting at your desk.”

“Oh that,” Harry said, leaning back “That’s life. Always testing. Always teasing.”

And everyone got quiet, with all the history and feelings on the table among the summer fruits, until Joanna said, “Tell about Curtis and his lawn care business, that he comes out here to cut the grass.”

“Tell what, Joanna?” he asked, getting up from the table. “You just told it.”

What he didn’t say—oh, he’d told Ruth, but no one else—was that he’d wondered whether the building being saved had anything to do with that morning in the sanctuary, the prayer scrolls pressed into his heart and his mind, perhaps detecting some truer truth, beyond the one he’d discovered. But Ruth had said no, probably not; that wasn’t how it worked. They weren’t stethoscopes. Still, he’d never forgotten that feeling, of being expected, led, and readied, everything implicit, everything emerging from some mysterious somewhere, and no questions asked.

From the Author: When I was a young girl, growing up in Detroit, someone told me that Jews and Blacks were minority groups. I remember turning this idea over in my mind and thinking that the person who concocted it must be terribly misinformed, because when I looked around my world, the only people I saw were Blacks and Jews. “Remnants, Like Dust in Pocket Seams” comes in part from that world, where together we two minority groups lived, went to school, and worked in uneasy proximity, never fully understanding each other, never fully welcomed by the surrounding community.

The story, one of the first I attempted as a new writer 10 years ago, comes from my father’s experience in the 1967 riots. It hooked me because of its odd juxtaposition of good luck and bad, but I couldn’t make it come out the way I wanted, so I set it aside. Then, in 2004, stalled with my other writing, I remembered it and pulled it out to see what this now-more mature writer might do with it.