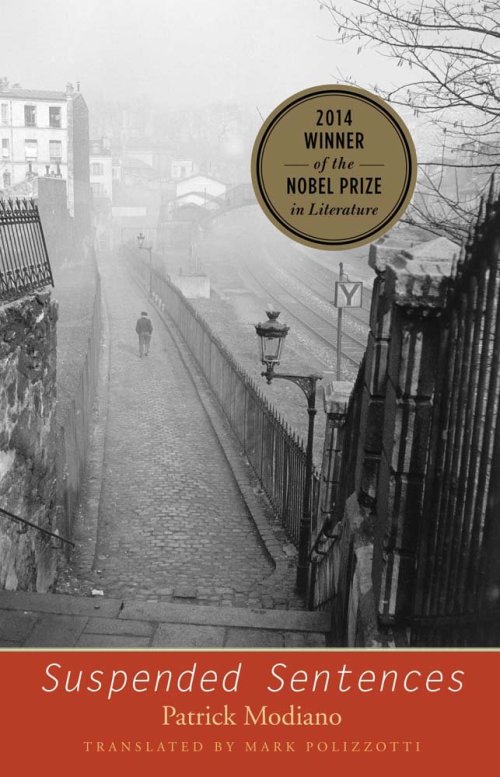

Suspended Sentences

|Patrick Modiano

Translation by Mark Polizzotti

Yale University Press.

2014, pp. 213, $16.00

by Marianne Veron

Paris in Slow Motion

On October 9th, 2014, when the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to the French writer Patrick Modiano, it seemed to his loving readers as if their long quest on his behalf had finally been fulfilled. Not that this shy and modest man ever considered fame or awards, but that he never even considered that writing novels was a career.

Reading Modiano’s books can be addictive in a slow-moving and affectionate way. He takes a reader on long walks along Paris streets, tirelessly looking for remnants of a time long gone—a café, a small park, a garage—moving back and forth between some precise memory of a vanished past where elusive characters appear and disappear, and the emptiness of the present where everything has changed.

The voice of the narrator is clear and melodious, the strolls reminiscent of the director Marcel Carné’s post-war movies. The nostalgia is soft and the descriptions are vividly beautiful in the clarity of their twin faces, past and present. One sometimes sees a Modiano devotee or a couple, following his path with book in hand, comparing then and now, strolling through one neighborhood or another.

In Suspended Sentences, three novellas progressively introduce the reader to the bifocal world of Modiano’s evocatively detailed but fragmented memory. Imagine a concert that starts with a sonata, is followed by a quartet, and ends with a full symphony.

In “Afterimage,” the 19-year-old narrator meets a middle-aged photographer in a café. Francis Jansen appears to have been worn out by his World War II experience and to be dropping out of life. Their conversation is sparse. Photos overflowing from open suitcases in the photographer’s studio raise questions, which sometimes elicit vague answers. Jansen alludes to being Jewish. With Jansen’s weary assent, the narrator undertakes to sort out, organize and make a list of the photos. “I had taken on this job,” the narrator explains, “because I refused to accept that people and things could disappear without a trace.” Years later, the narrator returns to where the studio was. The café and the modest old houses have been pulled down and replaced by modern housing.

In the title story, two little boys live with three or four strange women in a strange house, in a small town not far from Paris. Their mother, an actress always on tour somewhere, is hardly mentioned. The father turns up occasionally, or is said to be in Africa on business. Some evenings, men arrive on motorcycles or in convertibles, or later at night with a truck. They only have nicknames and close the door to talk with the women. The little boys put their ears to the door and hear the words “Gang of Rue Lauriston,” which fill their innocent imaginations with all sorts of mysterious and exciting ideas. These guardians of sorts are not unkind and seem to know the boys’ father well. In Rue Lauriston, the narrator recalls, were the feared headquarters of the Gestapo, where a cadre of French auxiliaries were willing, or forced, to serve, and where torture as an art was common practice. Nothing remains but the name of the street.

Here again, the narrator goes back and forth between the clarity of his spatial memories—the places, the garage, the dilapidated chateau further down the road—and the evasiveness of the characters. Between the puzzle of the past, which he never understood, and the fruitless quest of the present, the narrator finds tidbits of tantalizing information in old newspapers—prison sentences, shady wartime activities, the Gang of Rue Lauriston.

The third novella, “Flowers in Ruin”—Modiano’s full symphony—opens with press reports of an unsolved double suicide or murder in April 1933. Police accounts in old newspapers stir memories of stories from the narrator’s childhood and create or recreate other possible stories based on the information for which he relentlessly searches. Many years later, the narrator notices a weird-looking man—almost a tramp. He sees him again and again on the boulevard, studies him, follows him briefly. Then he sees him again in the university cafeteria, clean-shaven and properly dressed. Understandably curious, the narrator sits down at his table, and over coffee, they exchange a few words, but the man is diffident, mysterious. The stranger comes and goes.

More memories of chance encounters and his father’s associates arise, all of which he doggedly links to the circumstances of the double deaths of 1933. Eventually the stranger disappears for good, after entrusting the narrator with the black satchel he always carries with him. From here, the story twists in turns both ominous and obscure. The narrator wonders and ponders, returning repeatedly to the few facts he seems to be sure of, digging for more in the hope of finally understanding who those people really were or what they really did.

* * *

Modiano was born in the aftermath of World War II, in l945, in a working-class suburb of Paris. His father was a street-wise black-marketeer, Jewish, and, like the stranger in “Flowers in Ruin,” disappeared without explanation for long periods of time, never mentioning what he did or had done under the German Occupation of Paris. He once said that he had been rescued at the last minute from transit to a death camp for Jews, suggesting a close tie with the Gestapo.

Modiano’s books make numerous allusions to shady men and their activities, to jail, and to the ominous Gang of the Rue Lauriston. Among the trinkets Modiano once received from a Gang member was an elegant cigarette case in crocodile skin—a whole crate of which, he later learned, appeared to have been stolen. The elusiveness of men as father figures lies at the heart of Modiano’s stories, along with his vanishing childhood world, but his talent creates an almost dreamlike atmosphere. (Not surprisingly, the novelist was estranged from his father.) His mother was a Belgian actress, constantly on tour around the French-speaking world,

which involved long trips on trains and ocean liners to the Near East, Africa and even Asia.

Modiano grew up haphazardly, like a weed between cobblestones, dumped here and there with his younger brother by their flighty parents, with strange people who happened to be available whenever the need arose. He was 11 years old when his little brother—his only family, his only friend—died of leukemia.

Frequently handed over to oddball, laconic strangers who had no known conventional employment, Modiano’s fragmented childhood marked him with a consuming need to make sense of his scattered memories. He spent many years trying to figure out exactly who his father was and what exactly he had done, but gathered only a few shards, and the mystery remained for years. A sadness pervades his work—nostalgia for places destroyed, for people gone, fueled by an obsessive energy in the search, a hope beyond hope.

The Swedish Academy’s citation for Modiano’s Nobel honored him “for the art of memory with which he has evoked the most ungraspable human destinies and uncovered the life-world” of the Vichy regime under the thumb of the German occupation. Just a few of his earlier works had been translated, but Suspended Sentences in English was in bookstores before 2015. To Modiano’s own astonishment, the shy, modest French favorite has now crossed an international threshold.

Marianne Veron is a French translator of authors including Doris Lessing, Don Delillo, Andy Warhol and Herbert Lottman. She also edited Jewish Voices, the first French translations from the Hebrew of several books by Aharon Appelfeld, and a trilogy from the Yiddish by Sholem Asch.