The following interview was published in the March 1984 issue of Moment and has been reproduced in full. Read the original print version here.

In your book, Keeping the Faith, you very clearly state that it would be a bad mistake for Israel and the United States to conclude a formal alliance, since that would destroy America’s capacity to act as a mediator in the Arab-Israel conflict. In light of that, how do you feel about the recently concluded agreement between the two countries, and all the talk of a “strategic alliance”?

I think it was a serious mistake, for two reasons: First, I have great doubt about the substance of it, about whether it will bring any real advantage to Israel or to our country. There’s no written agreement; President Reagan’s statements, at least, just envision a committee to assess ways whereby Israel and the United States might draw closer in our relationship. So, beginning with the premise that there’s no genuine advantage for either of our two countries, I think it seriously weakens the position of the moderate Arabs among their Arab brethren. I know personally that King Hussein and President Mubarak, for instance, feel that this has been a serious blow to their status as potential peacemakers, as potential cooperators in carrying out the essence of the Camp David Accords, Resolution 242 and the Reagan initiative.

Second, I think it removes the U.S., to a substantial degree—as I said in my book, which I wrote a couple of years ago—from the role of a mediator, with objectivity and non-alliance with either side. The Arab world recognizes that our commitment to Israel’s security is unshakable. That’s a given fact, and I don’t think this agreement adds anything to that.

You refer to “Arab moderates.” We’ll get to your disappointment with Israel in the aftermath of Camp David in a bit. But do you want to say something here about your disappointment with these so-called moderates, and in particular with Hussein and the Saudis?

Yes. You have to recognize that there won’t be any genuine move toward a comprehensive peace until the Arab world in general, publicly and openly, recognizes Israel, her right to exist, her right to exist in peace. This is the essence of what I tried to achieve while I was in office for four years, not only with Sadat and the Egyptians, but also with the other neighbors of Israel, and of course with the Saudis as well.

The habit among the Arabs of seeking unanimity in their public statements almost inevitably brings about a lowest common denominator of achievement at their conferences. And when I talked to some of those you just mentioned during my recent trip to the Mideast, they indicated that they look upon the Fez statement, for instance, as being fairly compatible with the Reagan initiative and the Camp David Accords and UN Resolution 242.

Do you?

Only as interpreted by them in a private fashion. If you read the words there, they’re a step in the right direction, but a very minimal step. And any sort of recognition of Israel, which they imply is in the Fez statement, must be open, unequivocal and clear if it is to have any beneficial impact on the consciousness of the citizens of Israel or this country.

There’s a curious parallel here, isn’t there? In your book, you observe that American Jewish leaders quite often expressed themselves more moderately to you in private than they did in public. And now you’re saying that the same holds true for some of the Arab leaders.

It’s exactly the same. It’s there, it’s true. Even when I talked to the Syrians, to Assad, as well as to the Egyptians, the Jordanians, the Saudis, it became clear that their private statements are much more moderate in tone and much more constructive in nature than are their public statements, which are designed to be in compliance with a unified Arab world.

You’ve had some very laudatory things to say about Assad in the past, and these days that comes as a bit of a surprise to people. Would you share with us your assessment of him?

Early in 1977, my first year in office, I met with Assad, and was very encouraged by his forthcoming attitude. At that time, the only premise for seeking a comprehensive peace was in the so-called Geneva conference framework. This was the presumption of everyone—the Israelis, the United States, and the Arab world as well. And the main obstacle then was how the PLO representatives would be incorporated within the Geneva discussions. And I think that among the Arabs, Assad at that time was the most forthcoming in trying to find a way for the Geneva conference to be convened and to accommodate the Israeli sensitivity about the PLO.

Obviously, later on in the year, when Sadat made his visit to Jerusalem, Assad reversed himself completely, and was one of the most severe critics of the Sadat peace initiative. But if you will recall, even at the time of the Jerusalem visit, and during the months after, the presumption was still that the Geneva conference was the forum within which peace would be sought. It was only later, when I invited Begin and Sadat to Camp David, that the Geneva conference presumption was changed.

During your visit to the region last year, you spent some time with Assad, and you were again reported to have had some highly favorable things to say about him, even at this late date.

I know Assad fairly well on a personal basis. He is a brilliant, tough, aggressive, ambitious Arab leader.

Realistic?

I guess from a Syrian perspective he’s realistic. He recognizes the pressures and the opportunities for Syria. He and I disagree on most major issues, but he’s an intriguing man with whom to discuss Mideast problems. Assad has a great sense of humor; he’s very interested in not only Mideast but also world events; he’s quite provocative in his expression of ideas; he has little reticence at all in expressing his criticism of me, of the Camp David initiative, of other policies that I’ve espoused. He doesn’t pull any punches. And it’s a very good educational experience as well as an interesting personal experience to discuss matters with him. He still professes to be completely willing to withdraw from Lebanon if requested to do so by the Arab League and by the Lebanese government—although he has, since I met with him, added another proviso, which is that Israel not damage the integrity of Lebanese sovereignty.

In other words, that Israel not impose political conditions for its own withdrawal?

That’s correct. That is, that Israel not insist upon terms that Assad defines as being contrary to the security interests of Syria. He also professes, privately and publicly, a complete willingness, even eagerness, to discuss a comprehensive Mideast peace under the aegis of the United Nations, which I guess would mean a resurrection of the old Geneva conference idea.

Let’s talk about Camp David. Obviously, everyone is disappointed with the aftermath of Camp David, and you have, at the personal level, more reason for disappointment than anyone. I have had the sense, listening to you at the recent Emory consultation or reading what you’ve said elsewhere, that you feel more than disappointment, that you feel betrayed. Is that too strong a word?

When high hopes are not realized, there is a sense of great disappointment. I think “betrayal” is too personal a word; I don’t feel betrayed. We had hoped, as you know, that the Jordanian and Palestinian entities would join the talks, that the Camp David principles would be endorsed by a majority of the Arab world, that there would be a genuine grant of autonomy to the Palestinians, an end to the military rule or occupation which is now in its 16th or 17th year, that there would be a recognition of Israel by its Arab neighbors, that the settlement activity would be curtailed—I understood that it would be terminated— until the peace talks were concluded, and that the relationship between Israel and Egypt would grow in a friendly fashion rather than deteriorate as it has since the signing of the peace treaty.

So there have been a great number of disappointments. And, of course, there’s enough blame to go around, for our own country, for Israel and for all her neighbors.

In what sense for our own country?

I think in the last three years, we’ve not shown any high-level interest in pursuing the Camp David principles, with the one exception of the Reagan initiative, which I consider to be completely compatible with the Camp David Accords. That was a fine speech, prepared immediately after Secretary Shultz took office, and it expressed in very clear terms our own nation’s position. During the year and a half prior to that, there was no real pursuit of the principles that President Reagan finally expressed, and since that time, as you know, there has not been a high-level commitment to it.

Under Presidents Nixon, Ford and me, either the President or the Secretary of State could almost at all times be identified as an aggressive, personal mediator or potential mediator, searching constantly for opportunities to pursue any chance for Mideast peace. That has really not been the case for the last three years. And I think to that extent our country might be culpable. We’ve been occupied, or preoccupied, with the Lebanese crisis, of course, and that’s an extenuating circumstance, but even on that, Secretary Shultz has only been involved in the discussions on a very limited basis, for a very brief period of time. Whenever a leader of Egypt, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, for instance, has an inclination toward initiating a peace effort, he is not inclined toward dealing directly with a Strauss or a Linowitz, a McFarlane or Fairbanks or Rumsfeld. He needs to deal with a Vance or a Kissinger or a Muskie or a Nixon or a Carter or a Ford. And I think that’s an element that’s been missing. And I would hope that the Reagan initiative, or the principles expressed therein, would be pursued aggressively by our country at the highest possible level.

Yet you are in a better position than most to understand that the issues that prevent peace are not, in the main, technical issues. We are not in a situation where, if only someone could come up with an imaginative formula for administering, say, water resources, then everything else would fall into place. The fundamental problems are ideological, are they not? As I read your memoirs on Camp David, for example, they seem to say that what you had hoped to do was to substitute your vision of peace—a vision, as you saw it, shared by most Israelis—for Menachem Begin’s vision of land. And ultimately, you failed. Isn’t that an indication of the profound difficulty of external mediation?

I don’t believe that Prime Minister Begin or his successor has any intention of relinquishing any portion of the West Bank or Gaza. And this is a crux of the problem.

To me, this is in contravention of the Camp David Accords and of United Nations Resolution 242. If there were any indication on the part of the Likud or the present leadership that my statement just made is erroneous, it would send a wave of hope to the White House and, perhaps, to King Hussein, and, perhaps, to President Mubarak, and even others. The peace initiative could be rejuvenated.

At the same time, of course, all Israelis, and I, and almost all Americans, I think, have been deeply disappointed that no Arab leader, except for the Egyptians’, has come forward and said, “We recognize Israel, she has a right to exist, she has a right to exist behind recognized borders, she has a right to exist in peace, she has a right to be secure.” So there’s an element which goes to the crux of UN Resolution 242 and the Camp David Accords and the Reagan initiative which is missing on both sides.

So that’s why I said earlier that there’s enough blame to go around.

The relationship between Israel and Egypt, I think, continues to deteriorate. Egypt under Sadat or Egypt under Mubarak or Egypt under any foreseeable leader will have a natural desire to have harmonious relationships with other Arab countries. And I think that Mubarak probably has been acting the same as Sadat would have acted under similar circumstances, had he survived.

My hope is that Israel will withdraw from Lebanon, totally; my hope is that Syria will withdraw from Lebanon, totally. Now, with the recent second evacuation of the PLO from Lebanon, that presence has been drastically reduced, except for those under Syrian control. And if that should occur, then I believe the Egyptians would tend to reestablish the proper relations with Israel that existed prior to the Lebanese invasion.

But even then the relations would be no more than “proper,” wouldn’t they, until there’s some new breakthrough towards a comprehensive settlement

Yes, but that would be a step in the right direction. There’s still a fairly easy and friendly relationship between Egyptians and visiting Israelis. I had a chance to spend several days in the Upper Nile region last year, in ’83, and there were numerous Israeli tourists there, some as individuals, some in groups, and I made a point of talking to them whenever the opportunity presented itself, and they all commented favorably on the friendly reception they had received, in Cairo and in Alexandria as well as in the tourist spots of the Upper Nile.

So I think there’s a major element of truth still to what Sadat always maintained, that the people of Egypt wanted and want peace, the people of Israel wanted and want peace, the people of Jordan wanted and want peace, the people of Syria and Lebanon wanted and want peace. The obstacle is in the leadership. And the ancient political statements, the fear of one’s peers, the outmoded territorial ambitions, based on ancient claims—these are the obstacles to peace. I think that for a brief period of time, in the Camp David and the peace treaty months, there was an abandonment of those ancient impediments to peace. And Sadat believed that if any of the reluctant leaders would take an initiative for peace similar to his own, that their people would respond in an overwhelmingly favorable way.

And that that, in turn, would have elicited a response amongst the Israeli people that would have been irresistible to its leaders?

I think so.

That’s why such particular blame attaches to the Palestinians, and to the PLO. By condemning the process rather than joining it, they betrayed their own people and their own revolution. And so also the Arab moderates. They could have gotten a whole new dynamic going.

My hope is that the chance is not gone permanently, and that the opportunities are still there.

Tell us about your view of American Jews in this connection. From your memoirs, one gets the impression that you view them almost as an impediment to the peace process.

I don’t feel that way. There is a steady stream, as you know, of American Jews to Israel and to Egypt, and quite often they talk to me before they go and give me a report when they come back. They have a fairly easy access, the leaders do, to Egyptian leaders and to Israeli leaders. And I think they are a constant force for peace. They see the need for pursuing the principles of Camp David and UN 242, and I believe they are both sincere and effective.

Whenever a major dispute arises between the Israeli government and our own government, I think there’s a feeling among some of those same American Jewish leaders that they cannot publicly condemn those Israeli policies which they privately deplore.

I understand that perfectly; I would feel the same way. And there were times when I would make a statement or a proposal, particularly early in 1977, that might give us an opportunity to proceed with a peace initiative, when I would meet with Assad and comment favorably on the elements of our discussion that were constructive, or when I would call for the implementation of UN 242, and so forth, and the Israeli government would respond negatively, and quite often certain American Jewish leaders would comment compatibly with Prime Minister Begin’s criticisms. I recognize the reasons for that, and the justifications for it. So my overall sense of the American Jewish community is that it is a major moderating force, that it is a constructive element for peace, that it is an avenue for communication, particularly in private conversations, and that quite often their public statements are not compatible with their own private efforts and analyses, or there are different people involved.

At Emory, both you and President Ford spoke of your difficulties with Congress on Mideast issues, and indicated that Congress was simply too subject to pressures from the pro-Israel lobby, thereby blocking the effectiveness with which you could pursue the policies of the Executive branch.

I think that was primarily President Ford. I really didn’t have that experience, although there were times when the Congress considered reversing a decision that I had made. The most notable case was with regard to the sale of the F-15s to Egypt and Saudi Arabia. I thought that was a proper and necessary thing to do because of the dangers in the Persian Gulf, and our need to cement relations with Egypt, and, of course, many of the Jewish American organizations— probably unanimously—opposed it. But we prevailed. I think that was not always the case with President Ford, and I think he commented on that.

But that’s an element of American political life that’s both inevitable and desirable. I see nothing wrong with that.

Would you say something about the PLO and our policy towards it?

The PLO is comprised of highly diverse Palestinians; it’s a mistake to characterize all Palestinians or all those who support the PLO as terrorists. That’s a way to denigrate or condemn an entire race of people. And I think that’s a serious mistake.

There’s no doubt that the PLO has been involved in and has often publicly supported terrorist acts which I deplore profoundly, and which, I think, work contrary to their own interests and the interests of the Palestinians. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to Palestinians who live on the West Bank and in Gaza. They all profess to me their support for the PLO. But at the same time, they express quite frankly—some of them do—their disappointment with the policies of the PLO. They feel quite often that the PLO leadership is more concerned about the internal political struggle within the PLO or about financial considerations for the PLO than about the well-being of Palestinians who live in the West Bank and Gaza or who are refugees living in other places. But they don’t have any alternative or leadership.

I don’t know what will happen now that the second PLO-Arafat exodus from Lebanon has taken place. I have talked to others who have visited Israel since then, including Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. In general, the Palestinians in Jordan, Egypt, some in Lebanon, those in the West Bank and Gaza, look upon Arafat as the leader of the PLO, and as the leader of the Palestinian community.

King Hussein is in a quandary as to what to do. He would like to speak for the Palestinian community, but he has to be very cautious in doing so, because it might look as if he were trying to capitalize on divisions within the Palestinian world or the Arab world. He has a couple of alternatives if he decides to move on the peace effort. One is a public call on him by Palestinian leaders from the West Bank and Gaza to negotiate on their behalf or along with them. And the second alternative he has is the reconstitution of the Jordanian Parliament, which has been and will be comprised of 50 percent and more Palestinians, and to have the Palestinian element in the Jordanian Parliament call upon King Hussein to take an initiative toward peace.

Either one of these avenues might justify a more aggressive attitude on the part of King Hussein, if he is inclined to move that way. The third alternative is less likely, and that is that Arafat, able now to discount more effectively the Syrian influence on him, might encourage Hussein to join the peace talks under the Reagan initiative or within the Camp David framework or under the general rubric of UN 242. But the avoidance of those semantic titles is a very important point. King Hussein could not formally negotiate under the Camp David Accords; the Likud government in Israel would not formally negotiate under the Reagan initiative.

It’s not clear the Israelis would negotiate under Camp David, either. After all, the three leading members of the government there voted against Camp David.

I know that, and I’ve talked with them about it. Some of them profess that it was the Sinai aspects of Camp David that they deplored and that led them to void against the accord, but I think that may be not exactly accurate. In any case, it may be that it’s UN 242 that offers the broad umbrella under which discussions could take place, with Israel claiming that it’s negotiating under Camp David, and Hussein claiming that he’s negotiating under the Reagan initiative. I would like to see this happen, and I’ve used what very limited influence I have to try to consummate the Reagan initiative and to bring Jordan and Egypt and Palestinian representatives into discussions with Israel, with the United States present.

Do you see yourself as playing a continuing part in these matters?

No, only as a private citizen, as an analyst, as one who might explore possibilities. After the consultation at Emory, President Ford and I both went to Washington and met with Secretary Shultz, with National Security Advisor Bud McFarlane, with Ambassador Fairbanks and others, and also with the House and Senate Democratic and Republican leadership, to give them a report on the consultation, and, in effect, to offer our contribution if it was needed. But I think it’s highly unlikely that the Reagan administration would ask either President Ford or me to participate, and I’m not looking for an assignment of that kind.

A Mondale administration might.

There again, it would be unlikely. But if I thought there was an appropriate role for me to play, I would be glad to do so.

Can we talk for just a bit about human rights? You must have felt considerable pleasure and pride as well in the change of regime in Argentina. At the same time, you must be deeply disappointed in the Reagan administration’s abandonment of a theme you had so powerfully championed. Still, I wonder whether you’ve had any second thoughts regarding the wisdom of tying our foreign policy so tightly to the human rights question, whether any of the critiques that have appeared have affected your thinking on the matter.

Well, I was criticized more severely for overemphasizing human rights than for underemphasizing them. But if I have any second thoughts about the matter, they would be that I didn’t emphasize human rights enough. It’s not a general phrase or policy that can be ignored; it’s like a cutting razor edge, because the basic question of human rights is a very sharp instrument of domestic and international policy. I think it’s still the driving force within the Third World and among the vast majority of people on earth who are under some degree of suppression or deprivation. I’ve always felt—before I was president, and during and since—that our nation should be recognized by everyone on earth as the foremost champion of human rights—of democracy, of freedom, of self-determination, of escape from government-imposed suppression or murder of innocent citizens.

I’ve been disappointed in the last three years that we have in effect abandoned the human rights policy that was maintained not just by me but by almost all my predecessors. When I make a speech on human rights, the easiest place to find quotes of incisiveness and interest is in Harry Truman’s statements, for instance.

I thought about going to Argentina for the inauguration, and I’d like to go later on, but I thought my presence there would be a disturbing factor. Pat Derian [Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights during the Carter administration] was, she says, approached while there by thousands of Argentinians who asked her to convey to me their thanks for our human rights policy.

And human rights is a very fine phrase when it applies to somebody else, but when it applies to a situation in one’s own country, it becomes a matter of great disturbance and arouses fundamental feelings of defensiveness and even antagonism.

I wonder whether you see a linkage here to the Mideast conflict? I have in mind the basis of the relationship between Israel and the United States. There are those, of course, who believe that the fundamental connection between the two countries is that they share interests. There are others—myself included—who believe that it’s the values we share, more than the interests, that undergird the relationship. But if that’s so, then it’s important that Israel be perceived as a place where human rights are held very precious and defended strenuously.

In my own public comments about human rights, I’ve always talked about civil rights, and the status of minority groups in our country and the status of women. And on occasion I would mention in the same phrase or the same paragraph the question of Palestinian rights in the West Bank and Gaza, as well as of those living in the Palestinian diaspora. Those comments were always observed most acutely. But I don’t see any way ultimately to have peace in the Mideast without a recognition of Palestinian rights. It’s not compatible with the principles of democracy or freedom or human rights to have a large number of people, 700,000 or more, living—almost in perpetuity now—under military government. And it’s not an easy thing to solve. It’s something that quite often we’re inclined to ignore or to avoid—but it has to be addressed. And how to go about that element, and how to go about the element of Arab acceptance of Israel—those are the two questions of most importance, of most interest, and most charged with emotion and potential disharmony.

Finally, another change of subject, if I may: Early in your memoirs, you describe what it’s like to learn the mechanics of “pushing the button,” and you observe that no candidate for the presidency can avoid asking himself whether he would be prepared, if the circumstances were right, to push that button. Yet knowing a bit about you, as citizens are given to know about their presidents, it’s not easy to imagine that you would in fact be prepared, under any circumstances, to push the button, to initiate nuclear war. Are there circumstances in which you could have imagined a “first use” of the bomb?

That’s a difficult question to answer, because it involves the defense of Europe and the deterrence imposed upon the Soviets to prevent an invasion of Europe. We cannot match the Soviet conventional forces in Europe. If they know that we will not, or even doubt that we may not, use nuclear weapons…And without the counterbalancing threat of a nuclear retaliation, I think there would be an encouragement of a Soviet invasion.

But…

Yes, there’s always a “but.” And that’s the question that an American president has to be ready to face. But I think it would be counterproductive for any American president to say that under no circumstances, including a Soviet or Warsaw Pact triumph over the entire continent of Europe, would he ever use, say, tactical nuclear weapons. I just don’t think that would be an appropriate comment to make.

As you probably remember, under Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford and me, there was never any doubt in the minds of the Europeans or the rest of the world that the United States was in the forefront of the effort to reduce nuclear arsenals and to reach an agreement with the Soviets on arms control. When Jerry Ford and I were together last year, at his library in Michigan, we had a discussion with a large number of reporters, and neither Ford nor I nor any of the reporters who had covered us remembered seeing an anti-nuclear demonstrator while we were in office. And I would like to see our country retain, or regain, that position of trust among our allies and throughout the rest of the world that we are eager to have arms control agreements, are ready to carry out the terms of those that are in existence and to be aggressive in seeking an accommodation with the Soviet Union on reducing nuclear arsenals. This may be the paramount issue on earth, in the political world—to prevent a nuclear war. I think it is. How to go about reducing the threat of a nuclear war is a multi-faceted and very complicated issue, one element of which, of course, is to reduce tension in the Mideast. Another is to reduce tension between East and West. Another is to have genuine proposals on both sides on nuclear arms agreements that have at least a chance of being accepted, with slight modifications. But if both sides make propaganda proposals, which they know can never be accepted by the other side, then the substantiality of the negotiations is lost. And I’m afraid that’s the situation in which we’re currently living.

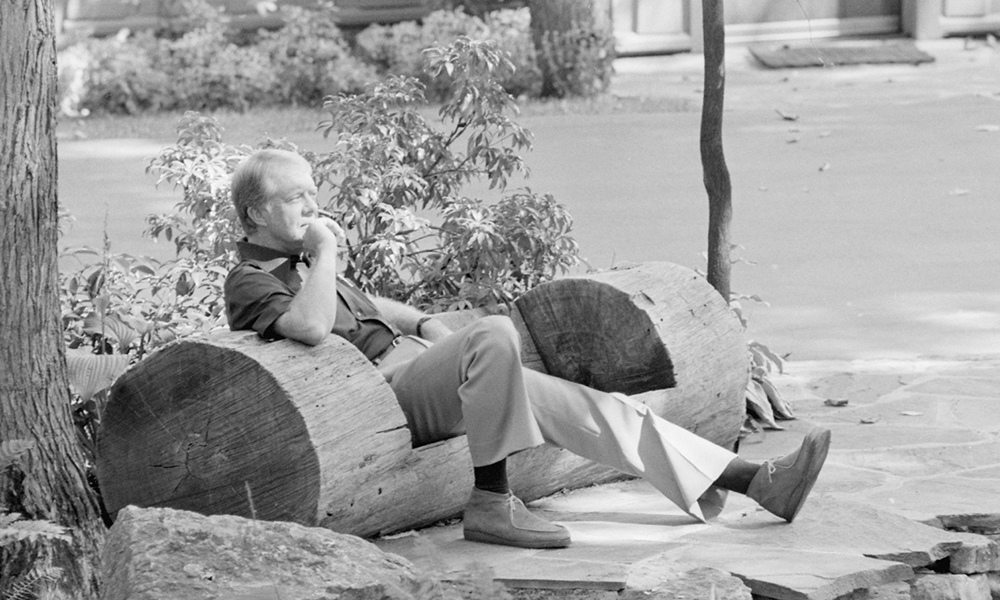

Opening photo courtesy of U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Right on Ms Epstein… there is a line connecting Nixon Reagan and Trump…

HATRED

Jimmy Carter only meant that it was a mistake to put a bunch of Jews and a bunch of Muslims together. You are immoral for trying to make that into something antisemitic. It was a TERRIBLE mistake to put Jews and Muslims together!! Look what has happened since that was done. A Jewish state would have been fine anywhere else on the planet except there.