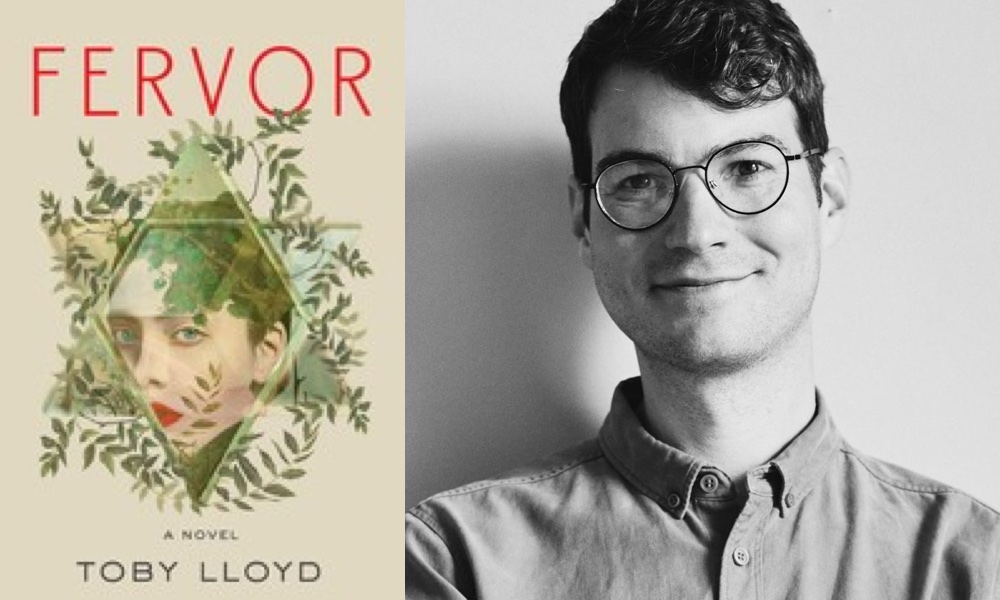

Fervor

By Toby Lloyd

Simon & Schuster, 288 pp.

Interview by Debby Waldman

The Rosenthals, the observant Jewish family at the heart of Toby Lloyd’s debut novel Fervor, seem so real that readers might be fooled into thinking Lloyd was raised by prickly intellectuals in a religious household in north London.

In fact, Lloyd, 34, grew up in a close, loving family in west London, the son of a culturally Christian father and a synagogue-going Jewish mother. Early on he identified as an atheist. Still, he couldn’t avoid religion. There were devout Christian relatives on his father’s side, and his mother was active in her liberal synagogue. His older brother embraced the faith, attending Hebrew school and becoming a Bar Mitzvah.

Lloyd, now 34, preferred reading about Judaism, particularly in novels by American authors such as Philip Roth, Saul Bellow, Bernard Malamud, Cynthia Ozick and Francine Prose. He also reads ancient texts and the Bible, the latter of which he considers a narrative source. While studying at Oxford University from 2009-2012, Lloyd attended Friday night lectures at Chabad, where he met religious Jews for the first time. When he arrived at New York University for a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in 2013, he joined a Jewish group that hosted weekly Torah studies and Shabbat weekends with Orthodox families.

He drew on those experiences when plotting the story of Eric and Hannah Rosenthal, who pride themselves on their high level of observance but can’t get their three children to follow their example. The two youngest are the biggest problem: Tovyah, like Lloyd, is an atheist, while Elsie, the only daughter, is rebellious and self-destructive.

The New York Times has hailed Fervor as “a lasting allegory of our dark historical time.” The Jewish Chronicle in London criticized it as “intriguing but infuriatingly flawed,” while giving a nod to Lloyd’s “lofty ambitions.” Lloyd spoke with Moment about those ambitions, his goal of exploring the different ways people live their Judaism and his qualms about religious observance.

There’s a lot going on in Fervor, which opens with the death of the Rosenthal patriarch, a Holocaust survivor who scared and possibly scarred his three grandchildren and was the unwilling subject of a book by his daughter-in-law, Hannah. But the bigger story seems to be about the many ways to be Jewish in the 21st century.

One of the things I wanted to explore was what it means to be a Jew at all. I think that was, once upon a time, not a very interesting question. It meant that you were part of a religious minority that lived in the diaspora. Today, I think it’s a very interesting question because it’s difficult to pinpoint exactly what it means to be a Jew. One of the things I remember in New York is meeting a [religious] woman who wouldn’t shake my hand because I was a man. That felt very alien to me, partly because shaking of the hand is a very unromantic and un-erotic gesture in my mind. So for that to be policed along gender lines is foreign to me. I found it interesting meeting these people and being aware that they represent the descendants of my ancestors in a different way than I am a descendent of my ancestors. If you go back far enough, we would all have been culturally similar, and today there’s this big divide between us.

How did your experiences, including your involvement with Jewish groups and organizations, inform the way you portrayed the dynamics of an Orthodox family and the son who’s rejecting any faith at all?

When I was in the MFA program at NYU, we had Shabbat getaways where you’d spend a weekend with Orthodox families. I felt very out of my depth but also very welcomed because the community was very welcoming. And along with the welcome there was pressure—there was a great sense that when this was over, you should behave as we behave. And some of the things we were told were things I couldn’t accept without pushing back against—for example, that it was wrong for a Jew to marry a non-Jew. Apart from everything else, my father’s not Jewish. How am I possibly, as an individual, to agree with that line of thinking? I wouldn’t exist. I didn’t think I could live the kind of life I want to live and also be part of that kind of an Orthodox community, and part of what the novel is about is a thought experiment of imagining people who don’t want to be part of that community but are born into it. And that’s what Tovyah’s character is: a misfit within the family he’s born into.

Elsie is also a misfit. In fact, a major plot point is that after disappearing for a few days at age 13, she returns home with no explanation, but very different: angry and out of control. Her mother Hannah is convinced she’s a witch, though the behavior could just as easily be attributed to adolescent hormones. Tovyah, her brother, thinks she’s a mess because their parents are too religious. What are readers to make of her personality change?

I think people need to read the book and draw their own conclusions. She becomes unrecognizable from the person that she was, and when this happens in a family, that’s a tragedy, and any effort to make complete sense of it is bound to fail. No one is ever going to get an answer that will completely satisfy them, and that’s the underlying pain that exists for this family. In the novel, Elsie becomes a sort of battleground over which the other characters are fighting.

Part of making sense of something is trying to get to the root of the problem. Hannah, especially, seems unwilling to entertain any other possibility for her daughter’s behavior than that she’s a witch—to the point that she writes a bombshell book about it. She’s so astute about things like history and facts. Why is she so obtuse about this?

One of the themes of the book is the perils of interpretation. Hannah feels disappointed in her children’s and particularly her younger son’s reluctance to follow her view of the world. There’s a line that is quoted toward the end of the book, from a rabbinical sage, who said that God is in everything, even in atheism. And why God is in atheism is because the atheist has to take responsibility. The atheist can’t say, “It’s up to God.” They have to say, “It’s up to me,” and that’s a form of goodness. Hannah, if you like, is the opposite of that. She is the believer who uses her belief to abdicate responsibility. Her attitude is, “I don’t have to sort things out because I am ultimately powerless. God is powerful. God will resolve things.”

It’s hard not to interpret that as an indictment against a highly observant life.

Part of my family is made up of religious Christians, so I’ve always been around very religious people of various faiths. And I think that any religious beliefs or practices that are very, very dogmatic and very hierarchical in terms of who sets the rules and who interprets the scripture very quickly leads—we see this in all the Abrahamic faiths—to the repression of women’s rights and to homophobia and other kinds of injustice.

That said, I do think there is a kind of religious practice and religious faith that is divorced from that kind of dogmatic literalism. And I hope that comes out in the novel. If you see [Tovyah’s friend] Kate’s attitude toward the religion, even to a certain extent [Tovyah’s brother] Gideon’s attitude toward the religion, it’s not just literalist. They see that there is a wonderful narrative inheritance, poetry and stories and myths, and they understand there is a lot to be said for the moral teachings of scripture. The problem is when you start saying that every word of it is the word of God, and that every word of it trumps everything that you might reason—that’s when you get into the territory of having stances that are unjust.