Sometime in the late 1970s, my father-in-law, who owned a bookstore in Chicago, arranged a book-signing party for the photographer Richard Avedon. It must have been a celebration for the publication of Portraits: Richard Avedon, a sumptuous book of gray-on-white photographs of celebrities and people in the arts. Many of these images are considered iconic, including his portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Truman Capote and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

At the reception, my husband and I introduced ourselves to the photographer, who shook our hands before he turned back to my father-in-law and pointed to my husband. “Your son,” he said, “has a terrific face.” Not to be outdone, my father-in-law answered in jest, “I’m more handsome than he is,” and Avedon shot back, “You’ve got an ordinary Jewish face, Stuart, but his is singular.” The compliment sparked a secret pride, which I stored away, but it was startling to have that glimpse of the artist’s method. Even without a camera, Avedon was a photographer interacting with faces and aggressively filtering what he saw. Some critics describe his pictures as “double portraits,” in which his distinctive but intangible response to his subject washes over his compositions. This explains how he could say, in an interview, “My portraits are much more about me than they are about the people I photograph.”

Avedon photographed the antiwar Chicago Seven (accused of conspiring to incite a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention), at Chicago’s Conrad Hilton on November 5, 1969. From left: Lee Weiner, John Froines, Abbie Hoffman, Rennie Davis, Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden and David Dellinger. (Photo credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of the artist. © The Richard Avedon Foundation)

I thought about all of this when I went to see Richard Avedon: MURALS, a powerful exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City commemorating the centennial of the photographer’s birth in 1923. On view until October 1, the exhibit is organized around three of the four massive, larger-than-life group portraits Avedon did between 1969 and 1971 that are now owned by the Met: The Mission Council, Andy Warhol and members of The Factory, and The Chicago Seven (the fourth mural, Allen Ginsberg’s Family, is in the collection of the Israel Museum). These works marked a turning point both for the photographer and for our country.

Avedon, like so many of the colossal artistic talents of mid-century America, came out of the Jewish middle class. His mother’s family owned a dress manufacturing company and his father and uncle were partners in a Fifth Avenue women’s clothing shop that was shuttered at the beginning of the Depression.

Outtake from Andy Warhol and members of The Factory: From left: Gerard Malanga, poet; Viva, actress; Paul Morrissey, director; Taylor Mead, actor; Brigid Polk, actress; Joe Dallesandro, actor; Andy Warhol, artist. NYC, October 9, 1969. (Photo credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of the artist. © The Richard Avedon Foundation)

Avedon’s interest in photography began early when he joined the Camera Club at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association (YMHA) during his middle school years and, later, at DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he and James Baldwin were coeditors of the school’s literary magazine. After high school, Avedon joined the U.S. Merchant Marine, where he was assigned to take photo IDs of the crewmen using a Rolleiflex camera his father had given him. In 1944 he enrolled in the Design Laboratory run by photographer and designer Alexey Brodovitch at The New School, and soon Brodovitch was promoting Avedon at Harper’s Bazaar, where he became known for his brilliantly creative and meticulous pictures of fashion and advertising.

Avedon’s fame was crystallized by the Hollywood movie Funny Face, loosely based on the story of his love affair with his first wife, model and actress Dorcas Nowell. The George and Ira Gershwin song, “’S Wonderful,” that Audrey Hepburn and Fred Astaire sing in the film (Astaire playing a version of Avedon), with the lyrics “You’ve made my life so glamorous / You can’t blame me for feeling amorous,” gets at the heart of Avedon’s vitality and charisma. By the mid-1960s, inspired by the civil rights movement, the protests against the Vietnam War, and the ensuing ruptures in American society, Avedon, who died in 2004, wanted to play a role in the push toward a more humane society and a new kind of art and photography.

The Met murals, gelatin silver prints, each one hinged and flush-mounted as a single panorama, are a distillation of that effort. They were created at just the time when Avedon’s celebrity provided him access to nearly anyone he wanted to photograph, from radicalized activists such as the revolutionary Puerto Rican Young Lords to General Creighton Abrams, commander of the entire military operation in Vietnam. His photographic technique—positioning subjects against a seamless white paper backdrop with minimalist lighting and shooting with a tripod-mounted 8-by-10-inch Deardorff camera—allowed him the flexibility to easily set up an ad hoc studio in Saigon or Chicago or New York. The idea of developing photographs on a monumental scale, creating images that were 10 feet tall and between 20 to 35 feet wide, may have been inspired by Warhol’s first blown-up silkscreens of Marilyn and Elvis.

Looking back, Avedon remembered wanting to reinvent the genre of the group portrait, which, as he put it, had evolved and developed from the Renaissance to 17th-century Dutch artist Frans Hals to the high school yearbook. Now he was printing massive photographs, including the raw black borders of his film negatives in the final images. This technique defined an unequivocal rupture in American history, while pushing forward the medium of photography and aligning it with the massive audacity of contemporary museum and gallery art.

For The Mission Council, Saigon, South Vietnam mural, April 28, 1971, Avedon assembled the U.S. generals, ambassadors and policy experts who ran the war in Vietnam. With very little time to photograph in the makeshift studio he rigged up at the American embassy in Saigon, he mapped out the top brass’ positions with careful attention to rank and influence. The only one missing was Ted Shackley, the camera-averse CIA station chief known to colleagues as the Blond Ghost. The images recall Avedon’s first gig as a teenager in the Merchant Marine, taking mugshot-style portraits of new recruits. (Photo credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, gift of the artist)

The Met exhibition is designed so that the portrait of 11 officials of the Saigon Mission Council (only one official from the on-the-ground group running the war declined to pose for the picture) is placed directly across from the composite photograph of Andy Warhol and his Factory—a conglomeration of art workers, porno film stars, writers and directors. Andy Warhol was still recovering from the 1968 attempt on his life, while the sexual liberties of his movies, parties and “happenings” presented an ongoing challenge to the American social structure.

The frontally severe Saigon Mission Council photograph was intended in 1971 to convey Avedon’s opposition to America’s involvement in Vietnam, but, upon closer examination, the portraits offer a deeper story. An assemblage of details come into focus against the stark white background—clipped and ragged fingernails, starched and drooping collars, folded pocket handkerchiefs, a hand stuffed in a pocket, the smirk of a mouth, the resolution of a jaw, eyes fixed ahead and eyes avoided. Added together, this is a theater of war and a human theater that Avedon understood.

“I know these men,” he wrote. “Those are the men who work on Madison Avenue, those are the men who work for the big corporations I work for. And I have worked for them all my life. I look at their faces and I know how much they drink. I know if they cheat on their wives. I know why they’re in Vietnam. I know what their relationship is to Asian people. I understand it and then I can photograph it.” That knowledge yielded insight into an array of emotions—self-reflection, uneasiness, the burden of responsibility, defensive arrogance, self-satisfaction and self-reproach.

The third portrait, perhaps the most famous, The Chicago Seven, is hung in an adjoining space. Showing the seven defendants who were accused of intending to incite a riot during the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention, it was shot in the photographer’s hotel room on the evening of November 5, 1969, the same day Judge Julius Hoffman declared a mistrial for the eighth defendant, Bobby Seale, and sent him back to jail. (Avedon left an empty space for Seale in the third panel of the triptych.) The series of individual portraits, later grouped together, is often compared to a police lineup; the image has a gritty and journalistic quality and comes across as more candid than the other murals. But, like them, it was meant to tell an epic story—in fact, when it was exhibited for the first time, in 1970 at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the crowd applauded in honor of the actual heroes of the antiwar movement. The Chicago trial was known for its antics and Jewish jokes, with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin referring often to the judge as Hitler, and Hoffman shouting at the bench: Shanda fur die goyim! Some of the details—Lee Weiner’s wire-rim glasses and Tom Hayden’s rope belt—have become iconic. But the portrait also reveals a weariness in the eyes, a motley quality, and exhaustion shared by the mostly young men (David Dellinger, the oldest by far, was 54 when the trial began). Although the panel rises 10 feet 2 inches high, it feels earthbound and generates a sense of vulnerability and sober forbearance not generally associated with revolutionaries.

The Met murals are accompanied by a number of fine smaller prints, all but one associated with those three projects. The one exception, a 1955 photo of the African-American singer Marian Anderson, is a homage to the miracle of voice with the contralto’s open lips forming an exalting “o.” By far the most poignant image in the show is a small group portrait, The Shoeshine Boys Project: Richard Hughes, social worker, with Vietnamese street boys. The picture was taken in Saigon two days before the Mission Council portrait, and it shows five barefoot, indigent boys in their early teens, standing on either side of Richard Hughes, a conscientious objector, journalist and actor later said to have been the last American to leave Saigon in the 1970s. After dodging the draft, Hughes came to Saigon on his own in 1968 and founded a children’s shelter that over the years expanded to several group homes. In the photo he stands with arms at his side, eyes straight ahead, while the boys, looking in all directions, express knowledge of that broken time, far deeper than any child should ever know.

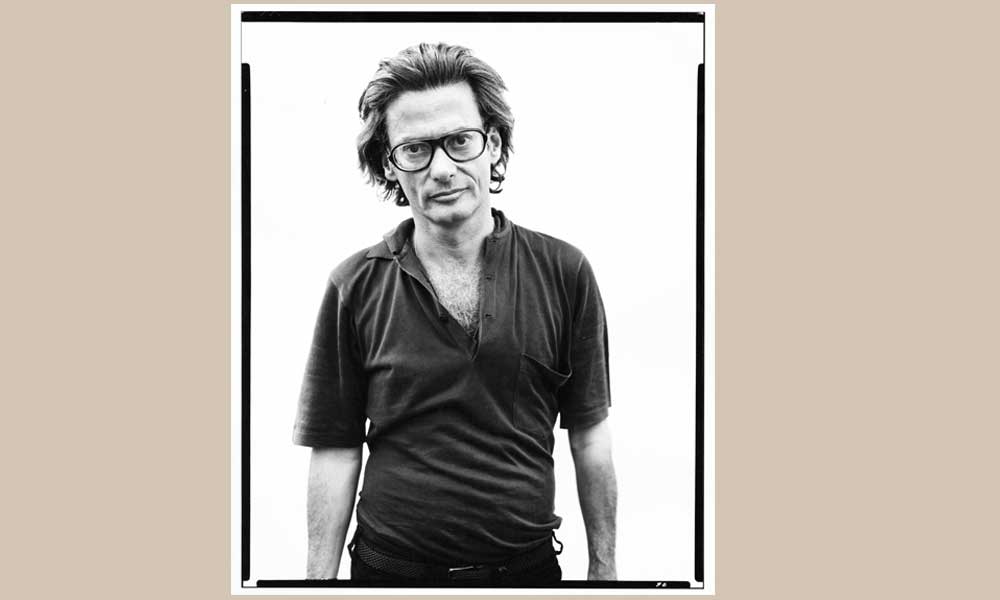

Opening picture: Richard Avedon (self-portrait), July 17, 1975. Taken at photographer Robert Frank’s Mabou Mines, Nova Scotia. (Photo credit: Photograph by Richard Avedon, © The Richard Avedon Foundation)

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.