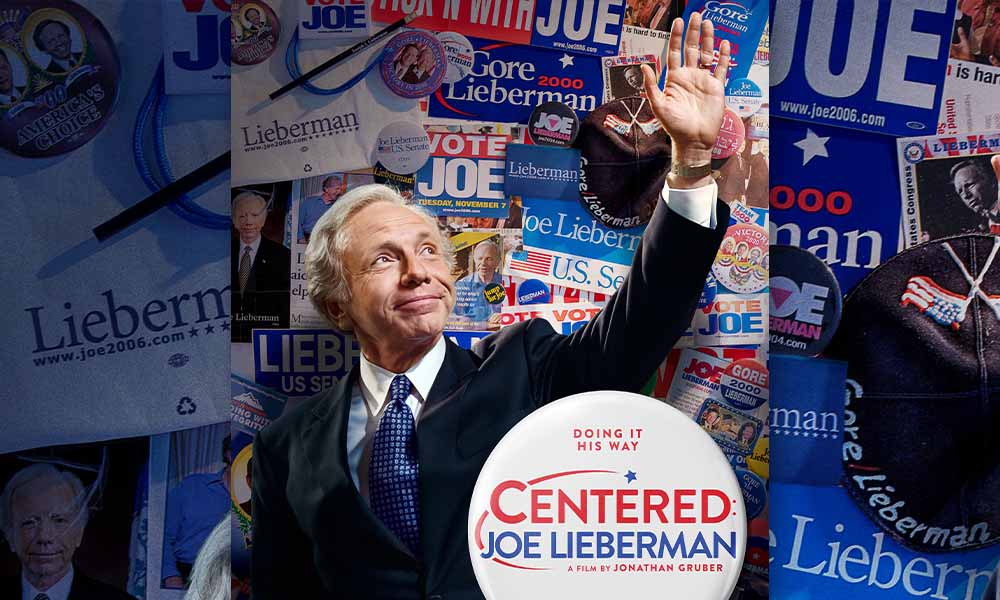

Film Review | ‘Centered’: How Senator Joe Lieberman Did it His Way

On August 8, 2000, Democratic Senator Joe Lieberman of Connecticut stepped before a microphone after accepting then-Vice President Al Gore’s offer to be his running mate. “There are some people who might call Al’s selection of me an act of chutzpah!” he said amid laughter. Indeed, that week’s TIME magazine featured Lieberman and Gore together behind the single word: “Chutzpah!”

Lieberman made history as the first Jewish American to be nominated by either party for vice president. Chutzpah (loosely translated as gall, nerve, even effrontery) was in abundance that day and throughout Gore-Lieberman’s ultimately unsuccessful campaign, which culminated in an electoral contest decided in George W. Bush’s favor in a 5-4 opinion by the U.S. Supreme Court.

But as the producers of Centered: Joe Lieberman demonstrate, chutzpah takes on an entirely new meaning when viewed through the prism of their subject’s 24-year career in the U.S. Senate—and not always in a good way.

Ultimately, Lieberman’s rise and fall (or semi-fall) seems more Shakespearean than biblical.

Writer/director Jonathan Gruber had full cooperation from Lieberman himself, plus his entire family and wide circle of political operatives, congressional and campaign staffers and many others. But as production on Centered was wrapping up, Lieberman died suddenly on March 27, 2024, at age 82. Critics (and there are many of them, principally Democrats) may dismiss the documentary as little more than a love ballad to a controversial figure with an unabashed “happy warrior” exterior. But the long list of friendly dramatis personae gives the film a certain heft.

Over the course of an hour and 16 minutes, we meet Lieberman’s wife Hadassah; his three children from two marriages; an array of Connecticut political pals from the early days (“I understand it’s not always easy to be my friend and political supporter,” he tells them); two sisters; and Ethan Tucker, Hadassah’s rabbi son from a previous marriage. Also, Malcom Hoenlein from the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, who talks about traditional Jewish misgivings over Jews drawing unwanted attention by running for high office. But, he adds, “If there’s any Jew we’d want to see [as vice-presidential nominee], knowing he would do the community proud and the country proud, it’s Joe Lieberman.”

The film showcases events on Capitol Hill in which Lieberman played a key role, from 1989 through 2012. The back-and-forth of that era now seems tame in comparison to the bile and vitriol that passes for political discourse today. A viewer up to date on the latest news from Washington could be forgiven for seeing those long-ago controversies—war in Iraq, President Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky, 9-11 fallout, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”—as quaint, almost sepia-toned and with a Scott Joplin soundtrack.

Judaism, of course, plays a leading role in the Lieberman saga. He was famous for putting aside political obligations in order to observe Shabbat. As the opening credits roll, Lieberman is seen donning his tallit, ritually kissing the tzitzit and gazing out onto the landscape of Riverdale in the Bronx, where he lived in retirement with Hadassah. Spliced in are video clips of his 2000 vice presidential acceptance speech, ending with him saying “Only in America.” A loss of that magnitude, decided not at the ballot box but by the Supreme Court, might have crushed some candidates. But not, Centered suggests, Joe Lieberman. “How do you cope with the idea that one Supreme Court justice basically cost you the vice presidency?” asks David Lightman, former Washington correspondent for the Hartford Courant. “He’s truly a man of faith, and I think that sustained him.”

Old photos and home movies taken with an unsteady 8-millimeter camera chart Lieberman’s Orthodox upbringing in Stamford, CT, decades before the town became a Fortune 500 corporate satellite to New York City. A drowsy, 1950s Hawaiian-type instrumental accompanies the narrative of Lieberman’s early years. His father Henry owned a liquor store. Marcia, his mother, was (as Lieberman described her) “a real people person.” She instilled commitment to “kindness, honor [and] reaching out to people who were not as fortunate,” says Lieberman’s sister Ellie.

Early pictures show a handsome boy with a blond wave above his forehead. “My religious upbringing is one of the reasons I ended up going into public service,” Lieberman says in the film. The election of Abe Ribicoff as governor of Connecticut raised Lieberman’s political antennae at age 12. Not only was Ribicoff Jewish, he was a centrist, and would later be a major mentor in Lieberman’s political career.

After graduating from high school in 1960, Lieberman enrolled at Yale, the first member of his family to attend college. The election of John F. Kennedy and Lieberman’s presence in Washington, DC, at Martin Luther King’s “I have a dream” speech in 1963 (and JFK’s assassination later that year) comprise the collective catapult that launched Lieberman in the direction of idealism and eventually public service.

After graduating from Yale Law School, he won a Connecticut state senate seat and served six years as the state’s attorney general. His political trajectory might have been straight up but for his breakup with Betty Haas (a fellow Ribicoff acolyte) after 16 years of marriage. In the documentary, Lieberman describes divorce as a “failure.” His daughter Rebecca says simply that the two were not compatible. “Honestly it was a relief when they decided to get divorced,” son Matt says. One of the issues (but not the only one) was Joe’s desire for Orthodox practice in the home and Betty’s relatively lukewarm feelings about it.

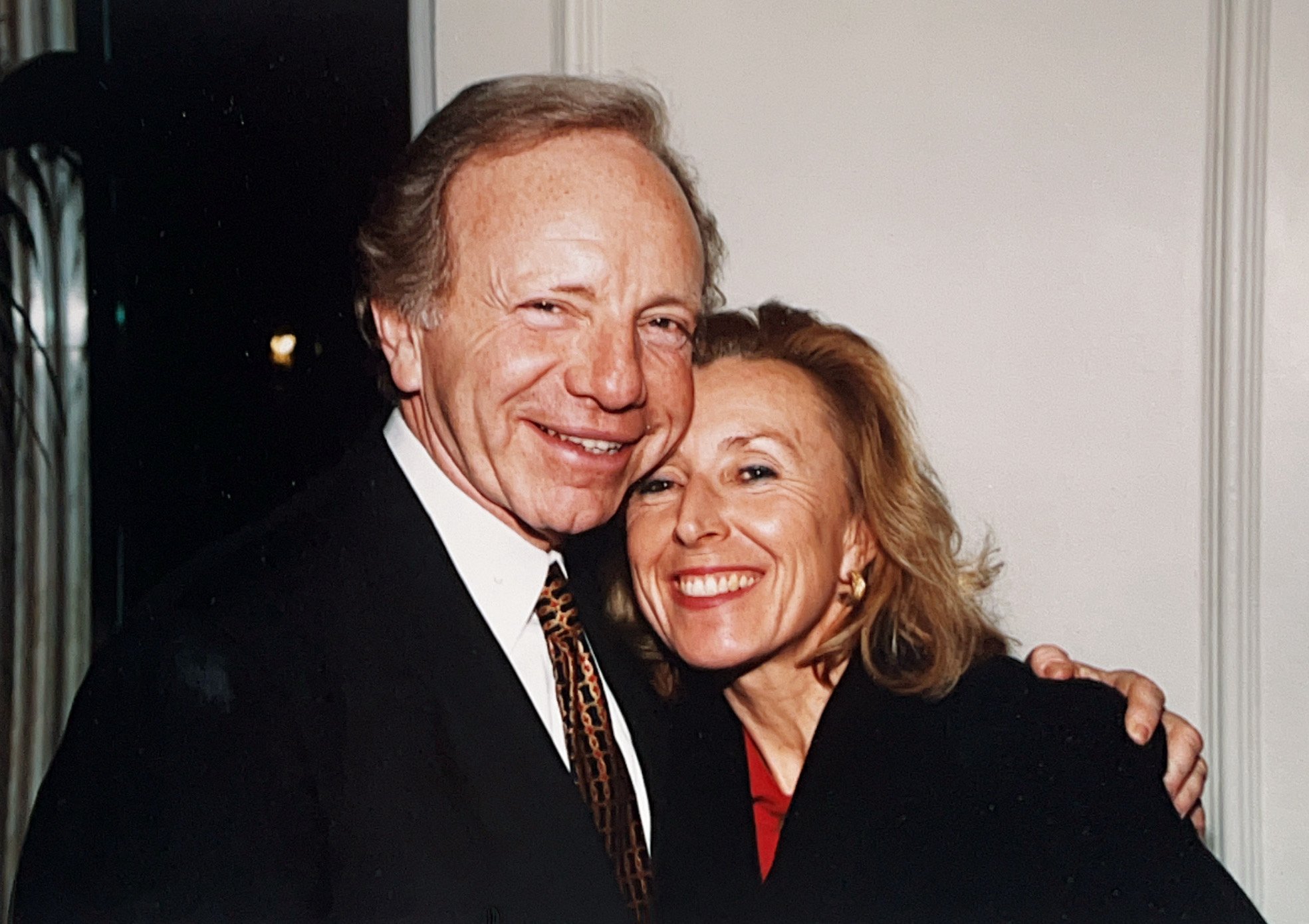

The year after the divorce, Lieberman met Hadassah Freilich (Yiddish for joyful, cheerful) Tucker. In Hadassah, Lieberman found his Orthodox soulmate. Lieberman’s sister Ellie recalls that Hadassah hid away/removed the chametz (leavened foods) before Passover just as their mother and grandmother had done, but wowed the family by also lining the kitchen sink with tinfoil. They married in 1982.

Joe and Hadassah Lieberman

In 1988, Lieberman rolled the dice and took on Connecticut’s moderate Republican Senator Lowell Weicker, attacking him from the right as insufficiently muscular on foreign policy. (Republican conservative Ronald Reagan, a veteran Cold Warrior, was in the White House.) Lieberman won the seat, and the documentary unearths footage of a victory rally in which Lieberman uncorked his passable baritone and led the crowd in his rendition of a personal favorite, Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” Singing that song turned out to be prophetic.

“It’s important to be open to civilized, respectful debate with people, to find common ground and get something done,” Lieberman says early in the documentary. “I have really been a centrist throughout my career.”

But the reality of Lieberman’s Senate career is that over the course of 24 years, his belief in centrism and compromise got enmeshed in his “I did it my way” view of political alignment. He was the first Democrat to support military action against Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s seizure of Kuwait, ultimately one of ten Democratic senators (out of 56) to authorize use of force in 1991. Lieberman in 1998 was the first of either party to speak out on the Senate floor in condemnation of Clinton’s “inappropriate” and “immoral” behavior in the Monica Lewinsky affair. (Clinton called him up a day or two later and told him that while he disliked the speech, Lieberman was right.) He also was an early supporter of President George W. Bush’s offensive against Iraq in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He continued his support for the military effort even after U.S. forces were trapped in seemingly endless civil war, and the rationale for the invasion—Saddam’s possession of chemical weapons—proved bogus. Ultimately Lieberman regretted his stance, but it doomed his brief bid for the presidency in 2004. In 2006, he lost the Democratic primary in Connecticut to seek another term in the Senate. His political career seemed over. But ever the confident and happy warrior, he mounted an independent candidacy—and won. It was an astonishing act of political jiu jitsu—taking Democratic hostility and carving out his own definition of centrism. “I was absolutely liberated,” he said.

The pièce de résistance, however, may have been in 2008 when he endorsed his close Senate friend John McCain of Arizona (a Republican) for president over then-Senator Barack Obama. Two years later, Lieberman was the 60th vote to pass the landmark Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) but not without exacting a price: deletion of the “public option,” which would have opened up Medicare and Medicaid to all who couldn’t afford a government-backed private healthcare insurance plan. Not a lot of Democrats shed tears when Lieberman announced he would not seek re-election in 2012. For the record, Lieberman’s many legislative successes should be noted: Repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” that allowed gays to serve openly in the military, creation of the Department of Homeland Security post-9/11, and creation of the 9/11 Commission to investigate the attack, to name just a few.

Centered is careful not to offer editorial judgments. It simply lets the various players, most prominently Lieberman himself, tell the story. But ultimately, Lieberman’s rise and fall (or semi-fall) seems more Shakespearean than biblical. Certainly there is nothing uniquely Jewish about standing up for what you believe and suffering the consequences. President John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage recounts the tribulations of eight senators who stood against their party and popular opinion and thereby paid a political price. For Lieberman, it could be argued that his admitted stubbornness and independence were less of a problem than the political ground shifting under his feet. Compromise to get something done arguably was a common trait on go-along/get-along Capitol Hill when Lieberman arrived in 1989. But within 20 years, comity was in a tailspin, shot down by purposeful divisiveness. In this dynamic, Lieberman may have stood out as antiquated, like a man walking through Capitol Hill with a handlebar mustache and a bowler hat.

In one of the last scenes in the documentary, Lieberman appears on Late Night with Conan O’Brien. The year is 2000, and he once again sings “My Way.” It is the documentary’s own coda to the life and career of a supreme centrist.

Centered: Joe Lieberman plays at Regal Cinemas (60-plus theaters) on March 18-19. Go here for more information.