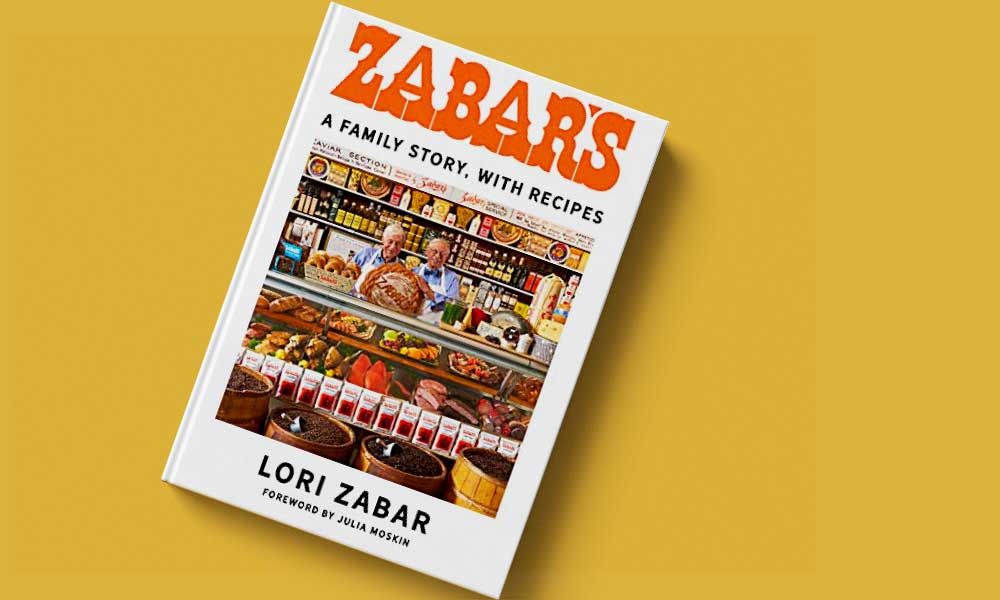

Zabar’s: A Family Story, with Recipes

By Lori Zabar

Schocken Books, 240 pp., $28.00

I lived three blocks from Zabar’s for 50 years. It was my corner grocery store, where I shopped weekly for breads and cheeses, smoked meats and fish, spices, sweets and, of course, bagels. On New Year’s Day, I often thought about rising before dawn and sneaking to the store, where clear plastic bags stuffed with empty blue and white caviar cans huddled on the sidewalk. The caviar had been spooned out of these cans on New Year’s Eve, and I fantasized that I might scrape enough of the precious eggs from each can to fill a small container. It remained only a delicious dream.

Zabar’s was and is iconic, a temple of culinary delights whose acolytes crowd into the shop every Saturday and Sunday to purchase the bagels, cream cheese, lox and whitefish that grace their weekend breakfast tables. It is big, noisy, astonishingly efficient despite long lines—checkouts take five minutes—and, despite its fame, retains something of the feeling of a neighborhood store.

Sometime after I moved to Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Zabar’s long, narrow, crowded shop on 81st Street expanded to a block-long behemoth. The expansion made space for fresh vegetables, ready-to-eat dishes, frozen foods, baked goods, freshly ground coffee and even more crowds. A small café and a mezzanine floor—crammed with discounted kitchenware, from large electric devices to the smallest peelers and scrapers—followed. Zabar’s now offered me (and others) the tools and ingredients that fueled the transformation of American food and cooking over the last 30 years of the 20th century. Zabar’s revolution was both harbinger of and participant in these changes. It began for me in the late 1960s when I dragged a stone crock of grainy Dijon mustard around Europe for a month only to discover, on my return, that the selfsame crock was available at Zabar’s and for less than I had paid for it in France! I loved the new store, even if I occasionally railed at other changes.

The men who had sliced the exquisitely transparent slices of orange nova that cascaded onto the counter, and who, more often than not, would offer you a sliver of fish to taste, were replaced by younger servers. They were always quick and efficient but sometimes lacked the precision of their predecessors. And although I shopped frequently at Zabar’s and had, as did all of their regular customers, a passing acquaintance with Saul and Stanley Zabar, the sons of founding father Louis, and their watchful and contentious partner Murray, I knew little about the business and how it had come to be.

Much of my curiosity has been satisfied by Zabar’s: A Family Story with Recipes, a detailed history of the family and the store. Unfortunately, its author, Lori Zabar, granddaughter of the founder, died shortly before the book’s publication. A historic preservationist, Lori was determined to be accurate and inclusive, and to her credit, she makes no attempt to smooth the rough edges of her family history, describing schisms, squabbles, character flaws, rivalries and even the Zabars’ occasional encounters with the law. She also documents her own life as a member of an immigrant family, giving readers insight into the ways in which children of immigrants somehow managed to retain their family ties and traditions even as they moved into the American mainstream.

Zabar’s offered the tools and ingredients that fueled the transformation of American food and cooking over the last 30 years of the 20th century.

The outlines of her story are familiar. In 1921, Louis Zabar and other family members fled from Ostropol, Ukraine, where a pogrom and the Russian revolution destroyed their hopes for a decent future. The Zabarkas, who, like so many immigrants, dropped the Russian ending to their name, were not the poor, often illiterate religious immigrants of Fiddler on the Roof fame. They were middle-class, secular and well-educated. Louis, who arrived in 1921, settled first with relatives in Canada, crossed illegally into the United States in 1922 and in later years paid blackmail to someone who threatened to expose him. He was always anxious until he became a citizen in 1942.

Zabar’s 1941 storefront. (Photo credit: Courtesy of zabars.com)

By all accounts, Louis was hard-working, entrepreneurial and highly ambitious. He spoke four or five languages but had a thick Yiddish accent and was often treated by others in the family like an uneducated peasant. His wife, Lilly Teitelbaum, tiny, energetic and outgoing, loved feeding everyone around her and was always ready for a good time. Lilly was sufficiently vain to shave several years from her age; she rarely planned ahead and was often hazy about details. But she was also warm and welcoming and, like the rest of the family, worked in the store when her help was needed. She and Louis had sons Saul in 1928 and Stanley in 1932. They were joined 13 years later by brother Eli.

The business prospered, but not without difficulties. During World War II, there were brushes with the law: Louis several times ran afoul of government price ceilings imposed by the wartime Office of Price Administration (OPA). At one point, he actually served 28 days in jail and paid a fine equivalent to $15,000 today. (Other merchants subsequently revolted against the confusion of OPA rules, which were later reformed.) Saul took over the business at his father’s untimely death at age 49, while Stanley went on to law school, returning to Zabar’s in 1970.

Although it seems incredible today, in 1961 Zabar’s was on the verge of bankruptcy. Saul appealed for help to Murray Klein, a tough, fearless, smart Holocaust survivor. Louis had hired him in 1950 as a manager, but he had left in 1957 to develop his own businesses. Murray returned to Zabar’s as a partner. He saved the business and shortly afterward involved Zabar’s in a series of price wars and lawsuits that, to everyone’s surprise, raised both the image and the profits of the company. Family squabbles waxed and waned, Zabar’s expanded, children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren did their stints behind the counter or in the back rooms.

Everyone was shocked in 1973 when Eli, the third son, broke away to create a food empire of his own. Born into a different world, he rejected Zabar’s enormous variety and low prices, stocked his shelves with high-end products and, with the dictum “less is more,” built an empire of his own under the name Eli’s Market on the city’s wealthy East Side. At his wedding in 1969, he decided to serve only caviar, champagne, strawberries and wedding cake. Mother Lilly was appalled. Unknown to Eli, she had a separate eating place set up in the house where her friends could dine more traditionally on roast chicken, salads, cookies and whatever foods she managed to sneak from the store into the house to celebrate her son’s marriage.

Through it all, like so many post-Holocaust Jews, the family matched their high levels of anxiety with equally high levels of achievement. They fell in and fell out. Against the odds, Eli and his brothers are still close.

Zabar’s very name evokes a bazaar (one more “a” would make it an anagram), but Zabar’s is also a landmark and a reminder of New York’s vibrant past. Here, immigrants, tourists, New Yorkers and celebrities (dozens were loyal fans, from Nora Ephron to Marlon Brando) could rub shoulders, try new foods and experience this unique gourmet grocery, which, like New York City, is constantly changing and reinventing itself.

Gloria Levitas is an anthropologist with a longstanding interest in food and culture.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

One thought on “Book Review | The Temple of Whitefish and Lox”

I grew up in Brooklyn pre-war (WW II) .. we had appetizing stores, basically “dairy” stores… in my childhood the place for lox was Macy’s 34th..yes Macy’s… they had Scotch lox.. and if you asked you could get a small sample… I did, but we never bought any……Lox really was too expensive, but occaisanily my father would take me to Dubrow’s (in B’klyn) for a part of a bagel and lox, with a rectangle of a “Philadelphia” cut diagonally…

Zabars actually became famous for it’s second floor of discount appliances… and of course I have tried Zabars lox, and pickled herring…

I have learned to love both the brands of Jared herring, but I bemoaned the loss of whitefish, until Cosco (can you believe it) came up with prepared whitefish salad, and by the way (probably) the best scotch lox (and at a reasonable price) that I have ever tasted.

I still am waiting to find jellied whitefish.