Book Review // A Bintel Brief

Advice Columnist-in-Chief

Reviewed by Clyde Haberman

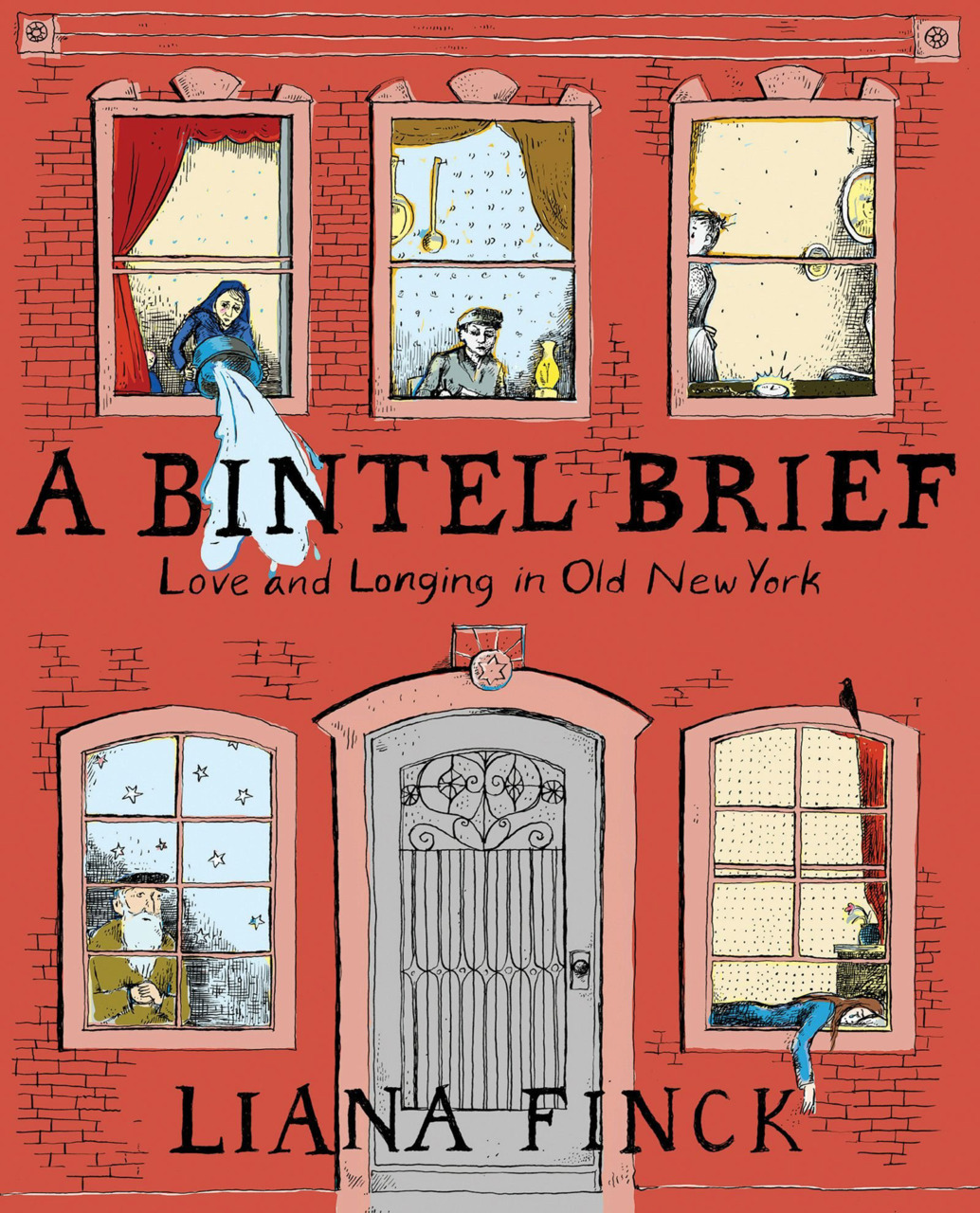

A BINTEL BRIEF

Love and Longing in Old New York

Liana Finck

Ecco

2014, pp. 128, $17.99

A heartfelt letter sent to a newspaper editor a century ago has long stayed with me. I happened upon it decades after it was written. With his soul in torment, a New York factory owner had turned to the editor for advice. He was not paying his workers— like him, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe—nearly enough for them to make ends meet. He had a business to run, and there were limits to the wages he could afford. Still, the suffering of his employees and their families tore at his heart. What should he do?

Memory being a fickle companion, the editor’s response has faded. Of greater interest to me was the writer’s tortured conscience—that, and his belief that a newspaper could ease his pain. For a modern fellow accustomed to advice columns dealing with more mundane laments about jealous lovers and cheating spouses, this letter was an eye-opener.

Thus was I introduced to the special nature of “A Bintel Brief,” the advice column that ran for seven decades in the Yiddish daily Forverts, The Forward. “A Bintel Brief,” meaning a Bundle of Letters, came into being in 1906, the brainchild of the Forward’s storied founding editor, Abraham Cahan. Cahan, who died in 1951 at age 91, became a sounding board for perplexed readers desperate for wise counsel. He routinely answered their plaints himself. For sure, there were jealous lovers and cheating spouses in their midst; when have there never been such types? But more compellingly, letters to the Forward came from newly arrived Jews struggling to balance life in the goldene medina with customs of the old country and imperatives of their religion. For these men and women, some of whom were illiterate and had to pay others to write their letters, Cahan was a guiding light.

The phenomenon of the bundled letters has been written about many times. Isaac Metzker, a Yiddish novelist and short-story writer, edited a collection of these missives in two volumes, published in 1971 and 1981, both under the title A Bintel Brief. Reviewing the first volume in The New York Times, the writer Jerome Weidman described The Forward’s column as having been indispensable to his immigrant family on the Lower East Side of New York. Abe Cahan “knew everything,” Weidman wrote. “Everything,” he repeated. “Everything that makes human beings, puzzled by life, terrified by life, write to a stranger, the editor of a newspaper, for help in their puzzlement and terror.”

“Except that Abe Cahan was not a stranger,” Weidman added. Not in his home, anyway, and surely not in many others.

Now we have a new work called A Bintel Brief. This one is from a young illustrator, Liana Finck, and is subtitled Love and Longing in Old New York. A news release from the publisher, Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins, characterizes the book as a “nonfiction graphic novel.” Well, it is not exactly nonfiction. Nor is it, strictly speaking, a novel. But it is graphic, its black-and-white drawings and text winningly executed by Finck, who illustrates 11 letters that she plucked from among the thousands that ran in The Forward: pleas from the open-hearted, the broken-hearted, the faint-hearted. The selections have been condensed and edited, she says in an endnote to this slender volume, but she assures us that her versions are “faithful in spirit and story arc” to the originals. Cahan’s replies are condensed as well, transcribed in Finck’s hand and bordered by a ring of teardrops falling from a single eye.

One letter, addressed to “Esteemed Mister Editor,” is from a poor woman who suspects that a neighbor has stolen a watch that her hard-working son struggled to buy with “every single penny that he saved.” Yet she hesitates to confront the neighbor, who “is even worse off than I am” and might feel humiliated. What to do? Unfortunately, Cahan does not answer directly. Rather, as a man of socialist bent, he offers this sad tale as evidence of “the wretchedness of the worker’s lot.”

A young man in Brooklyn who had fled a pogrom in the old country, letting his family suffer the worst of it, writes of his anguish. (Cahan says “this heart-wrenching letter” needs to be answered privately.) A cantor who has stopped believing in God wonders if he can continue practicing his craft. (No, Cahan says; that would be “without a doubt a shameful hypocrisy.”) A new bride asks if she is being reasonable or ungrateful to bewail the 52 pillows and 38 lamps that she and her husband received as wedding gifts. (Not ungrateful at all, Cahan says. As if to augur the modern bridal registry, he says that agreeing on “what you and your groom need in advance is a very good plan indeed.”)

Could anyone be more forlorn than a certain 22-year-old woman? Four years earlier, in 1911, her husband had rescued her from the cataclysmic fire at the Triangle shirtwaist company, but he perished when he ran back into the factory to try to save others. Even now, “I see the good face of my bridegroom,” she writes, and “the angel of death, also, is always before my eyes.” But there is a young man who wants to marry her. “I know that I can never love him,” she says. Please advise. (Cahan implies that she should wed this suitor. “She has suffered enough in her life already,” he responds,“and is advised to take herself in hand and begin her life anew.”)

Woven through the letters are imaginary conversations that Finck has with a conjured Cahan. He materializes magically from a scrapbook filled with Bintel Brief clippings that Finck’s grandmother once kept. This Cahan has a head shaped like a heart. A fedora, for some reason, floats above him in the air. Throughout, the old editor and the young artist schmooze about life and its vagaries.

This book, frankly, may not be everyone’s glass of tea. It is, no doubt, charming. But some readers may find the affect of a running dialogue with a spirit perhaps a tad too whimsical. Still Finck’s affection for “A Bintel Brief” and her sympathy for the distraught letter writers are undeniable. For the reader there is even a bonus: an illustrated recipe for schav, or sorrel soup, that is said to have come from Cahan’s wife, Anna. Ingredients include sorrel leaves, butter, a sweet onion, fingerling potatoes, vegetable broth and an egg. Ms. Finck allows that, instead of butter, Abe Cahan preferred chicken fat. It is not this book’s only indulgence in schmaltz.

Clyde Haberman is a contributing writer and former Metro columnist at The New York Times.