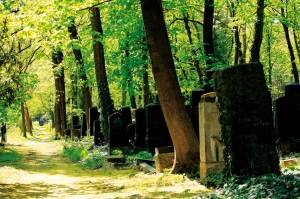

A documentary about a cemetery: It may not sound like much of a crowd-pleaser, but the German film In Heaven, Underground, directed by Britta Wauer and tracking the 131-year history of Europe’s second-largest Jewish cemetery, has been garnering some high praise. Last month, the New York Times called the movie, about the Jewish Weissensee Cemetery in Berlin, “poetic and exquisite.” Wauer spoke with Moment‘s Sala Levin about the past and present of Berlin’s Jewish residents.

What inspired the film?

It was not my idea—five years ago a program director from a Berlin television station asked me to make a film about this cemetery. I knew the cemetery and found it very special, but I felt that it wasn’t a good idea to make a film about it. You can walk in there and look around, and you can read online about the famous people buried there, so why make a film? I thought that no one would be interested. The only thing I was interested in were the stories behind the graves that hadn’t been told yet, so I tried to find people who are related in any way to the cemetery—people who have ancestors there, but also maybe people who work there. I had no idea how to find them. I wrote a article in a magazine called Aktuell published by the Berlin government for ex-Berliners. Many of them had to leave during the Nazi reign, so most of them are Jewish. I wrote a little article about the cemetery saying that if there was someone who wanted to help me by sharing their memorikes or photos, they would be welcome to write me or call me. I hoped for 20 or 30 responses. In two weeks we had 215 letters from everywhere: Australia, South Africa, South America. I was really overwhelmed. I thought, ‘Okay, I can think about really making a film.’ And then I had another problem: which stories to choose.

Most of the stories were related to Nazis and the Holocaust. I didn’t want to use stories only from this period, so I tried to find stories from the 1900s, when most Jewish people were really proud to be German and Jewish. I tried to find people with stories from post-war times, when the cemetery belonged to East Berlin. I tried to find stories from each time, for each period. I always chose from the unknown, the non-famous people, because you can read about the other ones in books or online.

What role does Weissensee play in the consciousness of the German public?

Most Berliners have heard of Weissensee, but never went there, though there were always people who were interested and went there. There’s a German term for this kind of Jewish cemetery—they call it an orphan cemetery, because all the relatives [of those buried there] were murdered or had to leave Germany. There’s no one really to take care of it. In the 1950s, the German government decided that they were responsible for Jewish cemeteries because they killed the people in charge, or forced them to flee. There are also private citizens who want to help, who go to the registry and say, ‘I really want to do something. What can I do?’ The people at the registry might say, ‘These are graves of families who committed suicide, so there’s really no one who can take care of the graves. If you want to, you’re welcome to.’ They choose one or two graves and say, ‘I’m the one who goes there now because there’s no one left to do this job.’ So for every birthday or date of death there’s someone coming, sometimes with flowers, or to put stones on it. They feel responsible for it. We, the Germans, are responsible. But there are also governmental intitiatives to take care of the mausoleums, because they say, ‘That’s something that belongs to our culture, and we have to preserve it.’

Are there other Jewish cemeteries in Berlin?

Since the eighteenth century, there were three Jewish cemeteries, but they were completely filled, so they had to open a new one. The oldest one was completely destroyed by Nazis. The next one closed in 1880, when Weissensee was opened. That one is untouched—it’s overgrown and really little compared to the Weissensee cemetery. Weissensee is the third Jewish cemetery. There are also other ones in that area that were destroyed.

There’s another Jewish cemetery in the west part of Berlin, which was opened around 1956. The Jewish community uses both of the cemeteries, but the plots in the West Berlin cemetery are all reserved now; they don’t have any space for Soviet Union Jews. So all the families who came here in the last 20 years from the former Soviet Union are supposed to go to Weissensee.

Can you tell me about contemporary Jewish life in Berlin?

There are some Jewish families in West Berlin. In East Berlin most of them were also communists and not really proud to be Jewish. Right now much of the Jewish community is from the former Soviet Union. Eighty to 90 percent is Russian, and most of them are not speaking German and don’t have any relations to Jewish culture, because they were not allowed to celebrate Jewish traditions in the Soviet Union. Berlin is the fastest-growing Jewish community in the world, but you have to look at the members of the community and see where they’re from and what they’re bringing. That’s why the cemetery changed that much—because the gravestones of the Russians are really different from the older stones. There are also Jewish people from the U.S. or Israel who live here in Berlin, but most of them are not officially members of the Jewish community—they’re just living here, or being an artist. So you find a lot of people on the street who speak Hebrew or people who have Jewish backgrounds, but they’re not in the Jewish community.

Many of your films deal with Jewish topics—where does your interest come from?

Everybody asks me why I’m making Jewish films if I’m not Jewish. It’s not Jewish-themed for me: It’s Berlin’s history, German history. I made a film about a Jewish couple who were also communists and had to escape to the U.S. After the war they were still communists, and had to flee from the McCarthy era, so they went back to Europe. I was really interested to make a film about the older communists who are still believers in the communist system. The ones who lived in America found it much better there. This woman was the founder of the pediatric department in a very famous hospital in Berlin, and my father was one of her students—so I have a special relation to the topic. I made a film about the Jewish quarter here in Berlin, but it was also a communist quarter. I chose this quarter to tell the story of German history over 100 years. That’s the quarter where I grew up, so I was always influenced by Jewish people. I’ve always been interested to know about Jewish people.

3 thoughts on “A Cemetery Story”

A fascinating Jewish cemetery is the one in Prague.

I want to add another comment regarding cemeteries. While visiting my cousins in Bratislava a few years ago, my wife and I ventured into a small cemetery within the city. The stones were fascinating, and the names were also. We sat down next to an elderly couple and I initiated a conversation. I started with my limited knowledge of a dialect of Slovak, then ventured with German and ultimately English. The man was quite well educated and spoke English. He explained his life during the German and Soviet occupations. Since the time was before the fall of the Berlin wall, he was still under the rule of Communism. We learned of the “quiet” resentment of the Czechoslovakian people to the fact of suppression since 1938 especially since the nation had a short existance after being formed from the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War One. First one totalitarian dictatorship replaced by another. Their children had escaped through Austria and live in Germany and France. My wife and I left with the feeling that he had unloaded a heavy burden – they never asked us about our life in America. He was interested only in why my father left Czechoslovakia in 1934.

A visit to a cemetery can be an enlightening experience.

Sounds like a very interesting documentary – thanks for letting me know about it.