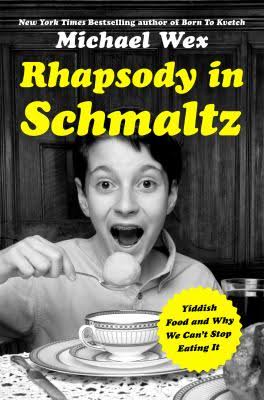

Rhapsody in Schmaltz:

Yiddish Food and Why We Can’t Stop Eating It

Michael Wex

St. Martin’s Press

2016, pp. 320, $26.99

Goose Fat for the Soul

by Gloria Levitas

Rhapsody in Schmaltz is not a book to devour in one sitting, nor should it be casually nibbled. Something of an oxymoron, this witty, entertaining volume overflows with food for thought and thoughts about food. It is stuffed with Talmudic arguments, biblical injunctions, slyly sexual linguistic tropes, and an exploration of the intimate relationship between Yiddish food and metaphor. Wex, a Canadian novelist, professor, linguist, Talmud scholar, cultural analyst and standup comedian, is best known for Born to Kvetch (2005), his hilarious yet profound analysis of Yiddish language and culture. This new volume is its more-than-worthy successor.

At first, the title seems odd. Why “rhapsody”? The word has at least two meanings for Wex: Its literary definition, as an effusive or ecstatic expression of feeling, might describe both this book and the complex and ever-changing dishes beloved by Ashkenazi Jews. The second is its association with George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, which has come to represent American music in much the same way that certain Jewish foods, such as bagels and lox, have become American standards.

And schmaltz? “It all comes down to schmaltz,” Wex writes, describing how Jews transformed many familiar Central and Eastern European dishes into Jewish specialties by substituting goose and later chicken fat for the pork fat or lard used by their Christian neighbors. Thus, foods common to everyone in Poland and Germany, such as crepes, dumplings and puddings, were adopted by Jews and became blintzes, kneydlach and kugels, and were bestowed with unique tastes and textures by adding schmaltz made of flavored poultry fat. Mix matzah meal with schmaltz and you have that most iconic of Yiddish dishes: the matzah ball.

What sets Wex apart from other Jewish food writers are his remarkably irreverent and often surprising interpretations of historical facts. No one else could note that “most national cuisines owe their character to the [local] flora and fauna, crops and quarry, domesticated animals and international trade. Jewish food starts off with a plague.” Wex also does not shy away from the less appetizing aspects of Jewish food culture. In considering matzah, for example, he makes the association between the “bread of affliction” and constipation and hemorrhoids almost painfully clear. And readers may be startled by his extensive discussion of the resemblance of triangular hamantaschen, knishes and pierogi to a specific feature of the female anatomy. Wex’s wider exploration of the numerous Yiddish sayings and food names that link food with sex ranges from the unusual yet warmly endearing to at times almost scatological.

Wex’s exploration of the numerous Yiddish sayings and food names that link food with sex ranges from the unusual yet warmly endearing to at times almost scatological.

Wex explores the seeming randomness of certain Jewish dietary laws. For instance, there is no single satisfactory explanation for the rule that forbids Jews to mix milk and meat, and different communities observe this law in different ways. Some Jews wait half an hour after eating meat before having milk; others require an eight-hour interval. Wex explains that the somewhat arbitrary law of not eating milk and meat together makes sense when viewed as part of larger Jewish ideas about separation, one of the more prominent and important aspects of Jewish religion and culture. Milk represents life, while meat signifies death. Thus, separating the two makes metaphorical sense. The Jewish idea of holiness is to divide the sacred from the profane, and Wex posits that this notion permeates and explains most Jewish dietary laws. He concludes that the existence of strict customs around consumption and forbidden foods has had one powerful and inevitable effect: Observant Jews cannot easily eat with non-Jews. The laws of kashrut therefore are an important reason for why Jews historically lived separately from non-Jews.

Wex has another lesson for us. He wants his readers to understand that, while dietary laws created the framework for Jewish cuisine, Jewish cooking itself is constantly evolving. This evolution, with its numerous variations, some small and some large, explains the wide differences found among dishes on the American Ashkenazi table.

The large number of traditional dishes made by Jews, observant or not, would seem to demand standardization. But even a cursory look at the myriad ways in which such dishes are prepared, the ingredients used to make them and every Jewish cook’s conviction that his or her family’s recipe is the most authentic version gives the lie to any notion of an unchanging cuisine. Just as there will never be a single form of Judaism, there will never be only one authentic recipe for a Yiddish dish. Similarly, “tradition” is not something fixed and eternal, but transitory and ever- changing. As an example, Wex points to bagels and lox, which first appeared on the American Jewish table in the 1930s, making this “traditional” dish, in his words, “somewhat younger than Tony Bennett.” Jews tweak even this tradition by debating bagel size, arguing whether or not bagels should be toasted and disputing if it is acceptable to spread peanut butter and jelly on them. And all these arguments occur even among the growing number of Jews who, despite having ceased to observe the laws of kashrut and the rituals of the Sabbath, nevertheless retain their love for traditional Jewish foods. Indeed, Wex argues that food may be the one force that holds Jews together in a rapidly secularizing world.

Ecstatic and effusive, elusive and unforgettable as goose fat on the tongue, this is a volume to treasure for its wit and irony, its deep historical knowledge and its remarkable candor. Wex skillfully blends culture, language and cuisine into a delectable and unforgettable literary treat.

Gloria Levitas is an anthropologist and author of five books. She has written on psychology and literature and has edited a collection of Native American poetry. She is a frequent commentator on food and culture.