An Israeli Artist’s ‘Postcards’ Tried to Heal the Pain of War

Ze’ev Engelmayer tracked the days of conflict with drawings shared online.

This summer I asked a friend, a photographer in Tel Aviv, if there were people in the Israeli art world who could tell the story of the trauma the country has gone through since the beginning of the Gaza war. “I don’t know if I’m even an artist anymore,” she had just said to me, although her recent glowing still life with apples, gladiolus and a blackbird belied that idea. Then she thought for a moment and suggested I look at Israeli artist Ze’ev Engelmayer’s daily “postcards,” posted every day on Facebook and Instagram.

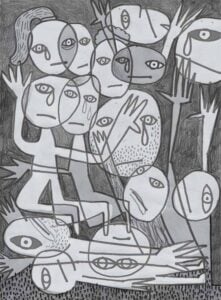

Anyone can go to those sites and scroll to the beginning of Engelmayer’s “postcards” to see his first Guernica-like pencil drawing of the Nova music festival, conceived just after the Hamas terror attacks on October 7, 2023. His stark figures are reduced to overlapping circles for heads, slashes for mouths, their puppet hands raised high in utter helplessness. The artist’s accompanying caption appears in Hebrew with an English translation:

“Trying not to think about it, and it comes back. The party at the wrong place. What were they thinking, what were they feeling, what happened there, in the moments when the music and the beauty and the love stopped, and the horror began?”

Under the caption, you can read 61 comments, mostly in Hebrew, but half-way through, someone has repeated the word “Horror” in English.

This is a hybrid art form, part comic strip, part poetry, an Arte Povera that is not mural-sized but made instead on 9-by-11 printing paper and added to day after day so it has come to resemble both a graphic novel and a memoir of war, but dependent upon social media platforms in order to be shared. The term “postcard,” which Engelmayer uses, is an inadvertent pun for English speakers since the art consists of a picture and caption literally posted every day on Facebook and Instagram. Soon after it’s uploaded, you begin to see a thread of comments written with characteristic Israeli intimacy, everyone writing back and forth with ardent responses and suggestions.

Engelmayer, who was born in 1962, has had several iterations in his career, first as an irreverent underground cartoonist, as well as an illustrator of newspapers, books and magazines for adults and children. His retro-style Haggadah, now in the collection of the Israeli National Library, put forward a list of alternative plagues, such as the plague of political corruption and the plague of memory loss, which he notes causes one to forget the lessons of the past. In 2016, he began to work primarily as a performance and protest artist, dressing as a naked woman in a huge pink foam-rubber and flannel bodysuit. This female alter ego, whom he named “Shoshke” and considered a superhero who was unafraid and could do anything, was a continuous presence at the 2023 Judicial Reform protests.

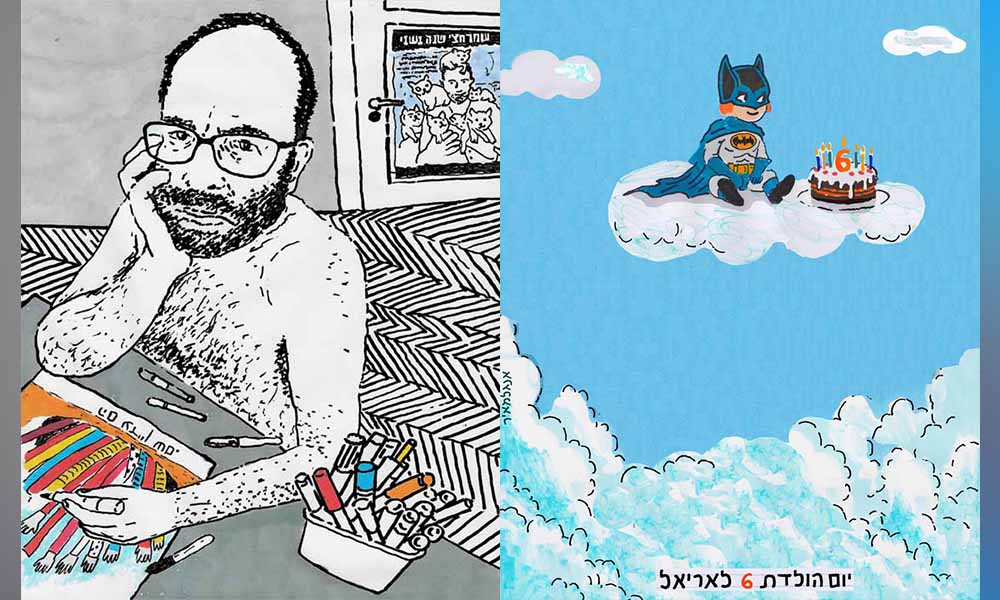

As a nude woman, but with a man underneath the costume, Shoshke was outrageous but in a gentle way; as someone said to me, “a little bit like Mrs. Doubtfire” of the 1993 Robin Williams film. After October 7, Engelmayer put aside his Shoshke costume and dedicated himself entirely to work reflecting an incisive and humane response to the complexities and hardships of the war. Tormented, like most Israelis, about the tragic fate of the hostages and the suffering of their families, his art often imagines an alternative to the nightmare and despair. One of his most heart-rending postcards was posted on what would have been Ariel Bibas’s sixth birthday. Ariel, kidnapped when he was four years old from Kibbutz Nir Oz with his parents and baby brother, was murdered in Gaza with his mother and brother one month later. Engelmayer imagined the little red-headed child sitting on a cloud in heaven and wearing a batman costume. A birthday cake by his side has seven candles, one for each year and an extra for good luck.

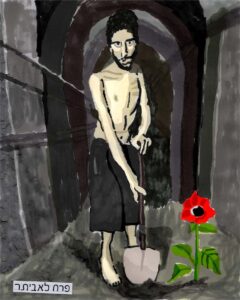

It didn’t take long for Engelmayer to become a central participant in the “Bring Them Home” demonstrations that began at Hostages Square in Tel Aviv and spread throughout the country, especially recently, after the IDF returned to Gaza City. His postcards, drawn on standard-sized printing paper with colored marker, range stylistically from simple, almost child-like pictures that resemble early UNICEF cards to his recent darkly moving pictures of hostage Evyatar David, who was infamously videoed by Hamas digging his own grave in a Gaza tunnel. Scanned and enlarged, Engelmayer’s pictures translate into powerful protest posters, and some have been blown up as large as six meters to stretch as banners across buildings. When I interviewed Engelmayer on Zoom, we talked about the development of the postcard project and how it has evolved organically.

“I started drawing on the terrible first day of the war. We heard sirens here in Tel Aviv and all day we were on our mobiles, watching, and it was hard to believe what was happening. I got into this room, and there were pencils, so I drew an image after [Picasso’s] Guernica. After that, I started drawing every day. I drew everything—the news, everything that I saw even while sitting in the stairway or the shelter. These were very sad drawings, but after two weeks I drew my first colorful picture. I drew Kibbutz Be’eri and I used colored markers because I wanted to show how pastoral it had once been, with water towers and houses with red roofs, and I wrote under it, ‘Something terrible is about to happen.’ The day after that, I drew the only postcard I’ve done showing the terrible things that happened in the kibbutzim. It was very difficult because I drew the violence. I was drawing for about five hours. When I finished, I opened my mobile and I saw exactly the same pictures of the terrors that had happened.

“Suddenly I understood that I didn’t want to draw that anymore. We have the horror in the news. And I felt I needed to find a way to give hope, to give myself hope. The next day, in the morning, it was raining in Tel Aviv and I thought if only the children in Gaza—the kidnapped children—would climb a rainbow and follow it to Tel Aviv. This was the first optimistic painting I made. And the day after that I made a map of hope, a map of the good things I saw. Then I began drawing with color every day. It was not easy because the days were very sad and there was so much tragedy. I’ve tried every day to find something good to say about what is happening.

“The day that really changed it all was the day I drew the first kidnapped woman. Her name was Yaffa Adar. Sometimes, in the news, they called her Grandma Yaffa. She was 85 years old. In news pictures she was surrounded by Hamas gunmen but she had a little smile, you know. And I decided, I’m not drawing the violence. I’m not going to draw how Hamas took her. Instead, I used exactly the same composition, but I surrounded her with an imagined group of women wearing colorful dresses and scattering flowers in the air. Four days after I drew this and published it, Yaffa was released as part of a temporary ceasefire deal. It was just a coincidence, but when she was released, seventy of the hostage families asked me to draw them postcards.”

Engelmayer told me that he first called the work “postcards” for the sake of expediency. It was the beginning of the war and he thought how art has a monumentality, it takes a long time, it has to have meaning, and it needs to be exhibited. But this was a unique moment, demanding spontaneity and improvisation. By calling the works postcards, he felt he could make them quickly and send them to whoever wanted to receive them. There was an appropriate modesty to the enterprise and he wouldn’t need to be apologetic about making art in a time of so much pain. Also, he told me, “In Israel, the word for postcard is gluya, derived from the Hebrew adjective galuy, which means ‘open’ or ‘revealed.’” Unlike a letter in an envelope, a postcard is something openly revealed, accessible to anyone. He hoped his postcards could be used to reveal stories about people touched by the war and simultaneously reveal his own feelings.

Over time, Engelmayer has developed an iconography that includes maps of Israel; the rainbow and dove; a halo of piano keys surrounding hostage Alon Ohel; the burly beard of hostage Eitan Horn; a hungry Palestinian child whose ribs are showing; and his own self-portrait, sitting in his studio, shirtless and unshaved. During the 12-day war with Iran, he drew an Iranian student he had previously met when he had gone to Lelystad in the Netherlands to give a lecture. She wrote to him during the war and after that he drew a picture, he said, in the style of Persian paintings, imagining the two of them together in a shelter “because we were in the same situation,” he told me. “Here we had rockets and sirens and she was experiencing the same in Tehran.”

When I asked how he sustains his sense of humanity during such difficult times, he told me a story about a woman who lives in Jerusalem. She had called him in December 2024, asking if he would make a postcard for her, hoping it would help her heal from the trauma she had experienced. Before the war, she had been working as a nature keeper in the parks, but during the first days of the war, she was called to serve in the reserves, in the Missing Person’s Unit, analyzing forensic evidence at the site of the Nova festival, piecing together physical remains in order to build a timeline and understand what happened to the people who were missing and those who had perished. This is a job that usually requires psychological preparation and training, but because of the scale and precipitousness of the terror attack there hadn’t been time. “What she told me was terrible,” Engelmayer said. “I heard her stories and I told her, ‘You know I’m really trying, in my postcards, to make something that will give hope.’”

What the woman described was appalling. Even the first time she was on leave from the army, she went home and saw her young daughter lying in bed, sleeping in the same position as a body she had seen among the terrifying remains of Nova. She was so shocked she couldn’t move. Everything the woman described was like that.

Engelmayer said he asked her, “Can you tell me anything good, any small detail?” And at first, she said no. And then she said, “Maybe when we found evidence, perhaps a ring that provided evidence of who it was, who it had belonged to, but it’s not really good; the ring tells us who it was, but it also tells us someone has died.” The next day, she called Engelmayer again and said she had thought of something. There was an instant, she said, during this terrible work when, as she put it, she had “gotten out from under the spell of it.” She remembered a day when they were walking through the field where the massacre had taken place. Part of it was burned, but there was an instant when she saw that there were thousands of small snails in the field. The tiny snails had taken her momentarily back to a time when, as a child in Haifa, she had seen an amazingly similar sight, a field filled with nature and life, with living snails everywhere. She said for that moment she had remembered that wonderful day, seeing the snails in the fields. After hearing that, Engelmayer drew a portrait of her with closed eyes, and the tears coming from her eyes look like snails. “Her story really got into me,” Engelmayer said. “For days, after the first time we talked, I couldn’t sleep at night, and in the morning, her story was still with me.” And he realized, he said, that if he drew a picture it would become a story and people would see it, and that would give it meaning.

Opening Image: “Self-portrait” (April 4, 2024) coupled with “Ariel Bibas’s 6th Birthday” (August 5, 2025)