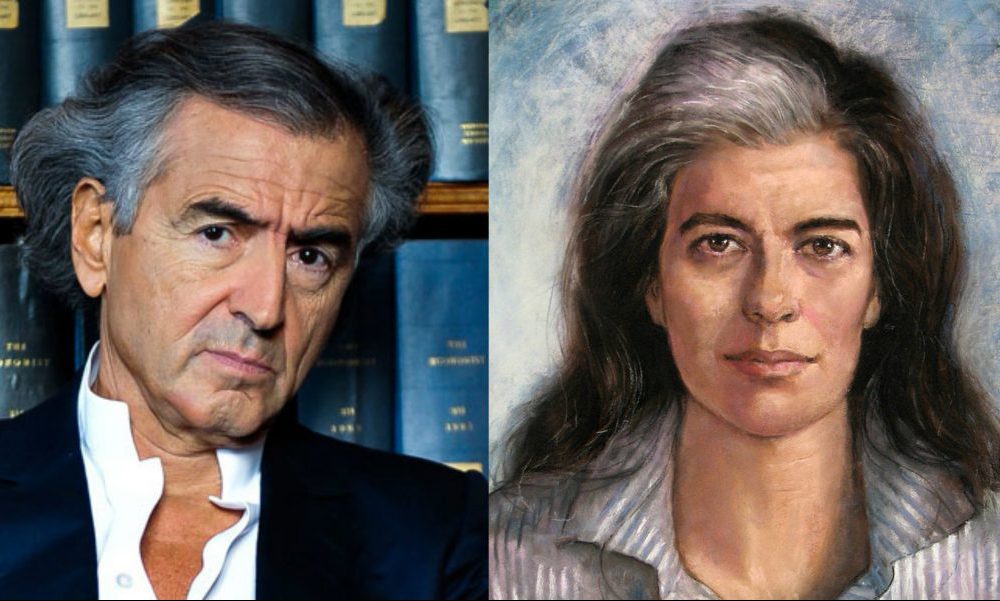

Why Susan Sontag and Bernard-Henri Lévy Spoke Out in Bosnia

By Liam Hoare

Into the hell of Bosnia entered Susan Sontag. It was July 1993, her second visit, and she was in Sarajevo to direct a production of Waiting for Godot. The city had been under siege for over a year; the Serb commander, Ratko Mladić, infamously ordered Sarajevo be shelled until it was “on the edge of madness.” More than 10,000 people would die in Sarajevo, as part of a conflict that began 25 years ago this month. “Nothing ever equaled the first shock,” Sontag wrote in a 1995 about the war, “the misery of daily life in the shattered city under constant mortar and sniper fire.”

Rehearsals were incredibly difficult. They took place in a gloomy, candlelit theater partly wrecked by shelling with enemy fire serving as the soundtrack. The cast, who could barely see one another or read their scripts, was malnourished and fatigued, slow to memorize their lines. They worked in Bosnian, with Sontag writing in the lines underneath on her English and French script. Props were makeshift and sometimes stolen by people wandering in and out of the theater.

“Until a week before it opened,” Sontag confessed, “I did not think the play would be very good.” Yet New York Times reporter John F. Burns noted, “To hear the silence of the packed house in the small theater in the city center was to feel the grief and disappointment that weigh on Sarajevo as it nears the end of its second summer under siege.” Her Godot ran for a month, part of a larger cultural festival, and Sontag was named an honorary citizen of Sarajevo for her artistic intervention.

“I was not under the illusion that going to Sarajevo to direct a play would make me as useful in the way I could be if I were a doctor or a water systems engineer,” but culture “is an expression of human dignity,” she wrote afterwards. Putting on a play in their own language allowed local theater professionals “to do what they did before the war” and thus “far from it being frivolous…it is a welcome expression of normality.”

Sontag was one of very few public intellectuals to visit the country in any meaningful way. Another was Bernard-Henri Lévy. France’s most famous public intellectual had been involved in Bosnia since the war’s beginning and attempted to persuade then-President François Mitterrand to intervene against the Serbs. Faced with indifference, in September 1993 he began to film Bosna!, a polemical documentary described by The New York Times as “a blunt, impassioned call for the countries of Western Europe and the United States to step in and halt the bloodshed.” Lévy “wants to prick the conscience of the world.”

Speaking in October 1994, Lévy said that he made Bosna! because of the ignorance and misunderstanding that surrounded the war, but also due to a compulsion to show something that many did not want to see. “It is a real war. It is not a fake war, it is not a synthetic war, it is not a video game—it is not a war without death as we like our wars now,” alluding to the 1991 Gulf War. “This is a war with blood, a war with flesh, a war with children like my children, like your children, who have their heads broken off. I wanted to show that.”

Bosnia, at that time, was a deeply unfashionable cause. It was dangerous, of course, yet Sontag believed there was a tendency to dismiss the Balkans at war as an old story as well as a failure to identify with the Bosniaks because they were Muslim, and therefore, unlike us. What even quite well informed people in the United States didn’t grasp was that “a middle-class Sarajevan was far more likely to go to Vienna to the opera than to go down the street to a mosque,” Sontag wrote. Sarajevo “represents the secular, anti-tribal ideal,” a city of mixed marriages and religious toleration “targeted for destruction” by Serb and Croat irredentists who coveted their Sudeten minorities.

Drawn by the romantic desire and compulsion to be present in times of war, to be a witness—one that would later take Lévy to Darfur, Libya and Kurdistan—for Sontag and Lévy, Bosnia-Herzegovina was, more importantly, representative of certain liberal ideas. Here was a multiethnic, multicultural democracy with Sarajevo as its colorful, cosmopolitan center. To abandon Bosnia was to say these things weren’t important. As Lévy wrote in 2008’s Left in Dark Times, “Bosnia was a miniature Europe…and we let it be blown up by shells, targeted by snipers, shredded by rockets and finished off.”

Particularly, it is impossible to speculate upon what drew Sontag and Lévy to Bosnia without looking at it through the prism of the Holocaust. Sontag critiqued Americans in February 1994 for “crying over Schindler’s List and saying, ‘Well, we’re not going to let the Nazis kill six million Jews again,’” while arguing that “nothing can be done” about another genocide in Europe. By August 1995, she had concluded that “if there were camera crews in Auschwitz, people would have said, ‘Oh, anti-Semitism is an old story in Europe. It’s really terrible what’s going on, but what can we do about it?’”

Sontag and Lévy’s responses to Bosnia were political, often polemical. They were also emotional, even visceral—to that extent perhaps only through art could they truly express their feelings about this war. Though Sontag wouldn’t have framed it this way, for she regarded herself as “hardly [Jewish] at all,” Sontag’s play and Lévy’s documentary were also informed by an understanding of Judaism as it relates to the universal.

Lévy talks about this in his most recent book, The Genius of Judaism. He stresses the compatibility of Judaism with progressive values while invoking Jonah, whose mission to Nineveh is, to Lévy, an instruction to engage with the non-Jewish world. “I have been to Nineveh,” Lévy writes. “I have spent a non-negligible part of my life and considerable energy working on behalf of people other than my own.” Bosnia was one such Nineveh. To be sure the Holocaust was a “warning signal,” as Lévy once put it to me, but present too evidently is this notion that Jewishness is at its most valuable, even beautiful, when it is brought into the lives of others.