Franz Kafka’s niece Věra Saudková, the daughter of Ottla, the youngest and favorite of his three sisters, began her recorded Shoah testimony with a simple family history: “My mother was the fourth child of the Kafka family.” When the interviewer asked if there was any chance she was related to the famous German-speaking Jewish-Czech writer, she answered in a soft, mellifluous voice and with a glint in her eye: “Yes, but he became famous only after his death and, actually, only after the death of his entire family.” The family, she explained, didn’t know he was a writer or, rather, considered his writing to be only a hobby, and his father, her grandfather, “had no respect for writers.” The story Věra told in giving her testimony resembles one of Kafka’s dark parables: “Once it happened that each of the sisters received some royalties. Each got two hundred crowns as inherited royalties. I remember how they met up, the three women, before the transport, each of them gripping her two hundred crowns. And with tears in their eyes, they said, ‘So our Franz really was a writer!’ And with this they went to the transport and never knew of the worldwide fame that came.”

In a more benign turn of fate, during the year 2024 (the hundredth anniversary of Kafka’s death) and stretching into 2025, scholars and admirers as far away as Bangkok and Taipei have been celebrating Kafka’s profoundly skeptical, original, disturbing and humane vision, ranging from his character Gregor Samsa, who awakens from troubled dreams to find himself transformed into some kind of insect, to the tribulations of Josephine the Singer, who serenades her fellow “mouse people,” though they refuse to recognize the power of her art. With a cool precision of style and sometimes even slapstick humor, Kafka created imaginary worlds contradictory enough to fit the experience of Modernism and what has followed.

There are now three concurrent exhibitions on view that focus on his life and art: “Kafka: Making of an Icon,” initiated by Oxford’s Bodleian Library and on display at The Morgan Library in New York City as “Franz Kafka” until April 13; “Kafka: Metamorphosis of an Author,” at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem until June 30; and “Kafka’s Echo,” which can be seen at the German Literature Archive in Marbach am Neckar, Germany, through June 22.

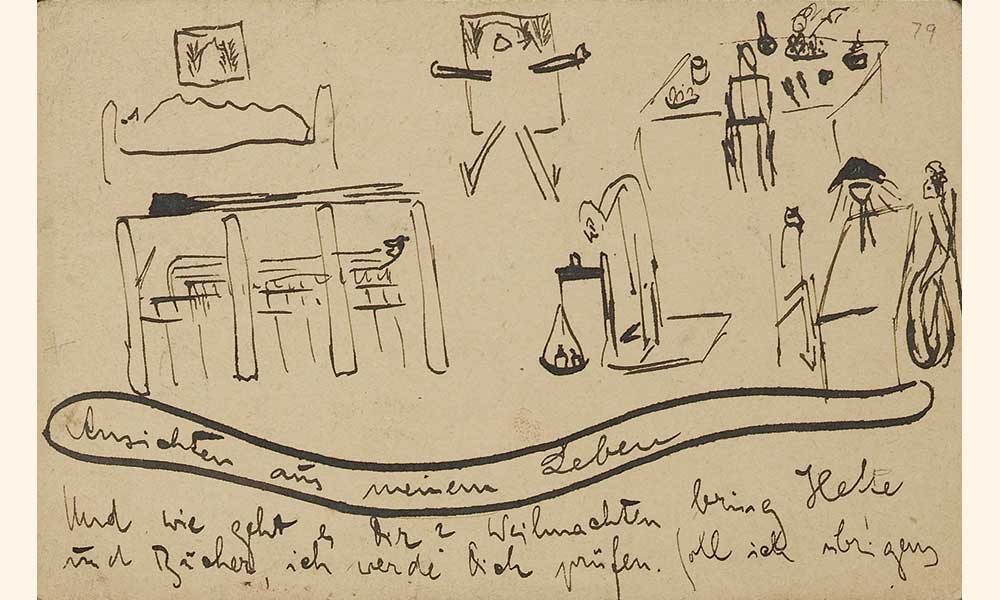

Franz Kafka, Black Notebook drawing. (Photo credit: The National Library of Israel)

All of the library exhibits display papers and manuscripts showing Kafka’s expressive though utilitarian handwriting, with its uppercase flourishes and firm deletion marks, sometimes sharply diagonal and sometimes running as horizontal curls. It is very moving to see the penmanship that first transmitted the writer’s dreamlike vision, which has a certain kinship to that of Russian writer Nikolai Gogol as well as to comedian Buster Keaton. The Morgan Library show draws primarily from materials in the Kafka Collection belonging to the Bodleian Libraries and includes the original ledger notebooks for many of Kafka’s works, showcasing especially The Metamorphosis and The Castle, where you can see long crossed-out phrases and many spots where the author altered “ich” (“I”) to “K.” With these changes, the beautifully written third-person narrative opens in the language of old-fashioned fairy tales that gives his work a sense of universality: “It was late in the evening when K. arrived. The village was deep in snow.” The National Library of Israel has the typed version of the painfully turbulent and accusative (but never sent) “Letter to His Father,” 45 pages long, the last three pages handwritten, and signed only “Franz.”

Postcard with six small drawings entitled “Snapshots from my Life” sent by Kafka to his sister Ottla in December 1918. (Photo credit: Jointly owned by the Bodleian Libraries and Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, Courtesy The Morgan Library)

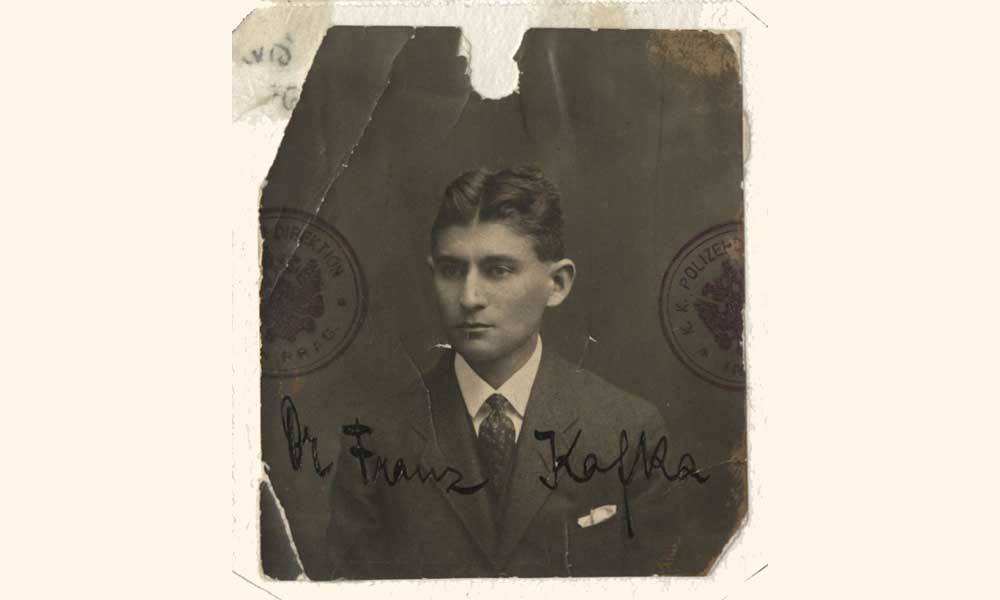

Photographs of Kafka, his family and friends, as well as letters and travel postcards, are on display in all shows, and they remind us that the man who created such a range of bewilderingly encased and encaged characters was thought by his friends to be congenial, compassionate, and even funny. Before he seriously dedicated himself to writing, Kafka experimented with drawing, and he continued making poignant, concise and whimsical sketches throughout his life. The Morgan Library exhibit displays a droll postcard Kafka sent to his sister Ottla from a sanatorium in a Bohemian mountain village with a set of playful sketches he titled “Snapshots from my Life.” The drawings, characteristically self-disparaging, show him sleeping in a broad bed, eating at a table with a variety of foods, and even being weighed, his tall frame (he was six feet) comically bent over to read the scale. Likewise, the National Library of Israel has an early sketchbook (1901-07) containing a series of stylized, efficiently spare India ink caricatures of lanky, weightless and androgynous figures that must certainly be parodies of Kafka himself.

Franz Kafka calling card, 1906. (Photo credit: The National Library of Israel)

In the 1950s and 1960s, most critics set aside Kafka’s Jewishness as a subject of little consequence. He was understood as an assimilated Jew, a man who had trained as a lawyer and died of tuberculosis before the Holocaust. His position as a forerunner of existentialism seemed much more important than his Jewishness. Today we have a better understanding that the man who wrote in his 1918 notebook, “What do I have in common with the Jews? I hardly have anything in common with myself and should stand very quietly in a corner, content that I can breathe,” was full of changeability and self-contradiction. Though he lived an acculturated and upwardly mobile city life, he had more than an inkling that the foothold of Prague’s Jews was precarious. From his vantage point, the Eastern European culture of Yiddish theater and the pioneering life of those who were emigrating to Palestine were enticing, while the disorientation of being a Jew in the center of Europe was at the core of his despairing perception of an unstable world without causality.

Photograph of Kafka and his sister Ottla on the farm, 1917. (Photo credit: Bodleian Libraries, Courtesy The Morgan Library)

At the Morgan Library you will find artifacts from the Yiddish theater that Kafka enthusiastically attended when he was in his late twenties: a poster for the popular play Der Vilder mensh (The Wild Man), a playbill from the Lemberg theater troupe, and a photographic printed postcard of Flora Klug, the charismatic actress, known as “the Gentleman Impersonator,” who mesmerized Kafka. Next to these are a letter to his young Hebrew teacher, Puah Ben-Tovim, concerning the teacher strike in Mandatory Palestine, as well as a page showing columns of German and matching Hebrew vocabulary words. It is now well-documented that Kafka was trying to master the Hebrew language, which he studied for seven years with the pipe dream that he would recover from the illness he was wasting away from and emigrate to Palestine; he even fantasized about starting a restaurant there. The National Library of Israel owns seven of the exercise notebooks Kafka kept while studying with Ben-Tovim, and his tidy practice sheets are on view there as well.

The tenacity of objects to endure and carry forward the imprint of those who have touched them is always astonishing. During Kafka’s lifetime, most of his short works were published in six small volumes (he was working on the seventh before he died) that received barely any attention. The remaining novels, letters, diaries and sundry manuscripts can be thought of as accidental survivors since his instructions were to burn them all after his death. This was explicit, both in conversation and in two letters to his friend and executor, Max Brod. The letter that is referred to as Kafka’s “First Will” is on view at the National Library of Israel. It reads as follows (this is an English translation by Willa Muir and Edwin Muir):

Dearest Max, my last request: Everything I leave behind me (in my bookcase, linen-cupboard, and my desk both at home and in the office, or anywhere else where anything may have got to and meets your eye), in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches, and so on, to be burned unread; also all writings and sketches which you or others may possess; and ask those others for them in my name. Letters which they do not want to hand over to you, they should at least promise faithfully to burn themselves.

Yours, Franz Kafka

Brod ignored his friend’s instructions and proceeded to dedicate his life to establishing the reputation he always believed Kafka deserved—editing the work, arranging for posthumous pub-lications, and eventually writing the first biography. It can be said that Brod saved Kafka’s writings twice since, in 1939, the night before the Nazis entered Prague, he escaped with the Kafka archive packed in two suitcases, which he carried onto the last train out, making stops in Poland and Romania’s Port of Constanţa. Carrying the same suitcases, he boarded a ship that stopped in Athens and Tel Aviv. For many years the fate of the papers continued to be convoluted and uncertain. In Israel, much of the collection was kept in the vault of the publisher Salman Schocken in Jerusalem, but during the Suez crisis, a portion was sent to his bank in Zurich for safekeeping.

When Kafka’s great-grandnephew was studying at Oxford, he met German scholar Malcolm Pasley, who asked if the family might agree to lend the texts to the Bodleian. From that chance meeting, about two-thirds of the Kafka materials came to the great library, partially gifted and partially purchased from his heirs. After Max Brod died in 1968, the Israeli government became involved in a 42-year-long dispute over ownership of what was left. During that time, some of the work remained in Swiss banks, some in safe-deposit boxes in Tel Aviv, and some in the home of Brod’s secretary and apparent mistress, who lived to be 101, kept about a dozen cats, and stored part of the archive in a “disused” refrigerator. Over the years, a few items were sold or disappeared, and the manuscript of The Trial as well as letters to Ottla were put up at auction and purchased by the German Literature Archive Marbach. In 2016 the Israeli Supreme Court ruled that the remaining Brod materials should go to the National Library of Israel, where the final papers arrived in 2019.

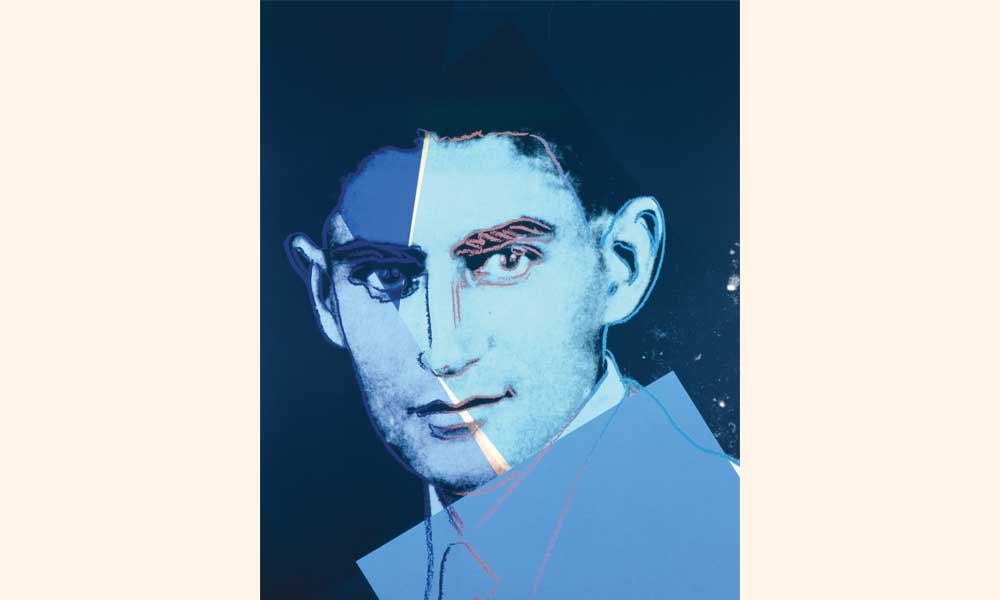

All three of the current shows give generous space to intellectuals, artists and writers inspired by Kafka, from Philip Roth to Haruki Murakami. In New York, Andy Warhol’s large portrait of Kafka stares out from a corner, raising its own blasphemous challenge. The work, a color screenprint, is taken from a 1914 photograph of Kafka and Felice Bauer, a woman to whom he was engaged twice although they never married. It was a turbulent time for the young writer, who already was unwell and only would live another ten years. While he was struggling with cycles of depression and suicidal tendencies, his creative energy was coming in fits and starts. That year he wrote the short story “In the Penal Colony” and began The Trial. Warhol, using his well-known technique, isolated an enlarged fragment of Kafka’s anxious face from the photograph and superimposed crayonlike lines and geo-metric planes of blue over the image, disturbing the surface. The portrait is part of a series titled “Famous Jews” that included, among others, Sarah Bernhardt, Albert Einstein and the Marx Brothers. Warhol’s early critics hated its vulgar commercialism and the audacity of marketing the great Jewish writer like a Campbell’s Soup can or a Brillo box. Kafka, of course, had a mordant sense of humor and a fine appreciation for twists of fate, and perhaps Warhol’s distasteful joke is also vindication for the deeply serious young writer who lived in obscurity but has become an icon. And this takes us back to Věra Saudková, Kafka’s niece, who remembered Max Brod’s telling her grandfather, “Your son, Mr. Kafka, is a writer!”

Opening picture: Portrait of Franz Kafka by Andy Warhol, color screenprint, 1980. (Photo credit: Courtesy The Morgan Library)

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.