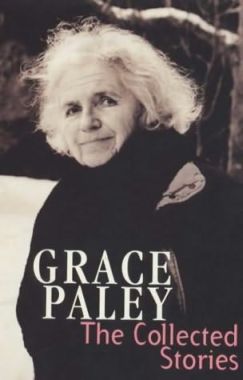

The Combative Pacifism and Poetry of Grace Paley

by Amanda Walgrove

Grace Paley was a Jewish pacifist accused of having an Irish temper. Armed with a strong Bronx accent and a stronger rhetorical voice, she took progressive matters into her own hands during a time when women weren’t always heard. As she asserted in one of her most well known poems: “It is the responsibility of society to let the poet be a poet. It is the responsibility of the poet to be a woman.” Paley wrote with a distinct voice that was shockingly independent, producing stories that were unashamedly lewd and hilarious.

Grace Paley was a Jewish pacifist accused of having an Irish temper. Armed with a strong Bronx accent and a stronger rhetorical voice, she took progressive matters into her own hands during a time when women weren’t always heard. As she asserted in one of her most well known poems: “It is the responsibility of society to let the poet be a poet. It is the responsibility of the poet to be a woman.” Paley wrote with a distinct voice that was shockingly independent, producing stories that were unashamedly lewd and hilarious.

Lily Rivlin’s 2010 documentary, Grace Paley: Collected Shorts, screened last month at the New York Jewish Film Festival, beautifully captures the spirit of Paley’s life and work by incorporating videos of readings, interviews with family and friends, and her own footage which dates all the way up to her final book party in 2007. As a working woman passionately devoted to activism, Paley wore many hats. She was a devoted mother, groundbreaking writer, beloved teacher, and self-described “combative pacifist.”

Thrust into politics from an early age, Paley was the daughter of Russian socialists who immigrated to the U.S. in order to keep their children out of jail and safe from pogroms. Her neighborhood was dotted with women sitting on boxes and lawn chairs speaking Yiddish, English, and any conglomeration of Eastern European tongues. “Gracieh,” she could still hear her grandmother cooing. Paley recalls that the name “Grace” was her sister’s idea, remarking that when said in a Jewish accent, it was as good as any other name. She credited her parentage for a great deal of her boldness in character and authorship, having grown up in a household where argument was expression. She was quoted in a Washington Post article, saying, “I thought being Jewish meant you were a Socialist. Everyone on my block was a Socialist or a Communist…” Before reaching the age of twelve, she joined The Falcons, a group for young socialist children.

Paley once said that you didn’t have to live an interesting life just so you could write about it. But if she wanted to, she definitely had the material. The five-foot one-inch force of a woman had a substantial FBI file resulting from her unrelenting involvement in protests for peace and the women’s movement, which was, in her view, the most important movement in the world. Political activist Donna Gould credited Paley with redefining militarism and war in feminist terms. Rabbi Sharon Kleinbaum shared her story of the first time she was arrested with Paley. She hadn’t wanted to attend the peace rally but ended up being thrown into the mix. Grace turned to her and said, “See, you just can’t get out of your responsibilities.”

While defending women in a political setting, Paley gave voice to them in her poetry and prose. She once said, “Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life.” Her books of short stories, The Little Disturbances of Man, Enormous Changes at the Last Minute, and Later That Same Day were lauded for their honest, fearless and humorous depiction of urban family life. Her daughter Nora referred to her as a kitchen writer because she never had a desk but was always listening and remembering. For the working mother, life was a series of interruptions, and she found the stories in them.

Paley was tenured at Sarah Lawrence College and quickly became somewhat of a surrogate mother to many of her loyal students. She was said to have conducted her classroom like an orchestra before the music plays. The testimonials of students and colleagues in Rivlin’s film illustrate how much of an impact Paley had on those who knew her. Even after her passing, she lives on through her writing, which is a master class of its own. And now, thanks to Rivlin, longtime friends and those new to her work can enjoy a glimpse into the life of a passionate writer, activist, and mother. Those who have been inspired by her devotion to politics can carry the message forward: “These are our times. They’re global times. We live through them together. And we are lucky to have literature and art and children.”

2 thoughts on “The Combative Pacifism and Poetry of Grace Paley”

nice article. thanks.