Susannah Heschel: The Rabbi’s Daughter

Following in the footsteps of her father, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the biblical scholar is at the forefront of the march toward social justice and reframing Judaism in the tradition of the prophets.

As many Jewish families set their seder tables this year, they will place an orange next to the parsley, egg and shank bone—a contemporary ritual invented by Susannah Heschel, the biblical scholar, Jewish feminist and daughter of the late Jewish philosopher and civil rights icon Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Legend has it that the custom came about after an Orthodox Jewish heckler interrupted one of Susannah Heschel’s lectures on feminism, shouting, “A woman belongs on the bimah as much as an orange belongs on the seder plate!”

But if you ask Heschel, she will tell you a different story: how the rapid spread of AIDS in the 1980s both terrified and alienated her friends in the gay community. Cruel messages from some in the Jewish community did not help, including a rabbi’s wife who famously pronounced there was as much room for lesbians in Judaism as there was for a crust of bread on the seder plate. During a trip to Oberlin College, Heschel discovered a feminist Haggadah that proposed just that—placing a crust of bread on the seder table as an act of solidarity. Inspired, Heschel sought to create her own symbolic gesture. Since Jewish law does not permit leavened bread in a home during Passover, she peeled a mandarin orange for her seder guests. The segments were bound together in a single sphere, just as, she explained, all Jews and all of humanity should be.

She invited everyone to take a segment of the orange, make the blessing over the fruit, and eat it to show solidarity with lesbians, gay men and others on the margins of the Jewish community.

Following in the footsteps of her father, Abraham Joshua Heschel, the biblical scholar is at the forefront of the march toward social justice and reframing Judaism in the tradition of the prophets.

Heschel is not surprised that the fable of the heckler endures. It echoes a familiar pattern: It transfers credit for a woman’s vision to a man. For the last 50 years, Susannah Heschel has been trying to set a place at the table for female scholars like herself. Just as her father fought alongside Blacks in their struggle for a place at the table during the civil rights movement. Just as Jews have been fighting for their place in this world for thousands of years.

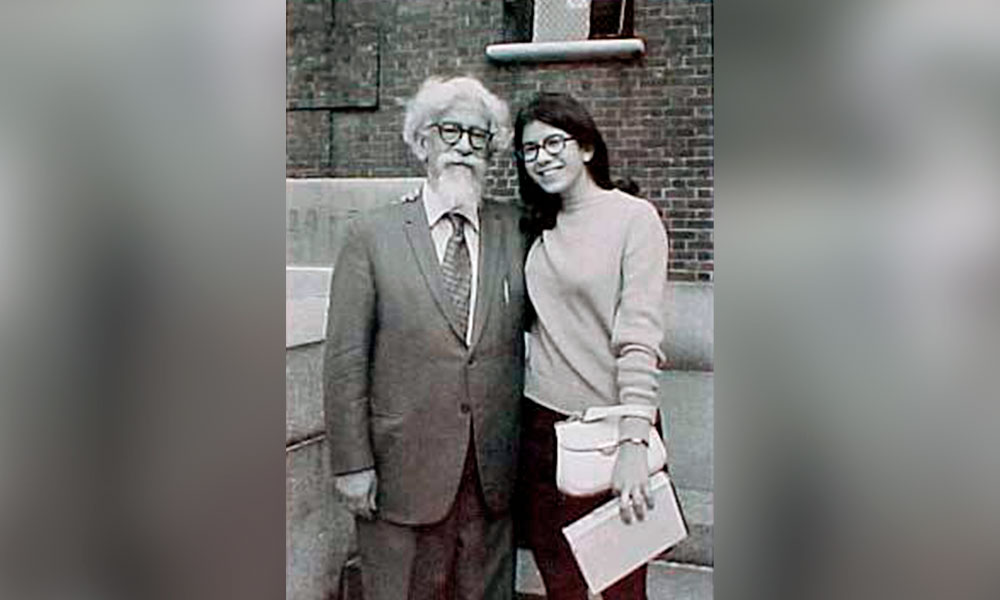

Susannah Heschel and Abraham Joshua Heschel. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Susannah Heschel)

As the only child of a Jewish legend, Susannah Heschel, a professor whose expertise includes the history of biblical scholarship, antisemitism and Jewish scholarship on Islam, also has spent considerable time and energy guarding her father’s legacy and correcting the multitude of misconceptions that have grown up around him. Scores of biographies, articles and dissertations have been penned about Rabbi Heschel since his death nearly a half century ago. But very few get everything right, his daughter says. Most recently, Yale University Press released a volume on Abraham Joshua Heschel as part of its Jewish Lives series that included a well-worn myth that it presented as fact—about the night the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. rang the doorbell of the Heschel home right before Havdalah. To mark the end of Shabbat, the story goes, the men lit the Havdalah candle and smoked cigars—a portrait of camaraderie and friendship that writers like to include in their hagiographies about Rabbi Heschel.

Susannah Heschel and her parents at her bat mitzvah. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Susannah Heschel)

But Martin Luther King Jr. never came to their house, Susannah Heschel says. She has told authors that time and again. But no one ever takes her word for it. “I just get discounted on these things,” says Heschel, now the chair of the Jewish Studies Program at Dartmouth College. “What is that about?” After all, Heschel is not only a noted scholar, she is the rabbi’s daughter and lived with him during that historic era. Her years of studying feminist theory, working in a male-dominated profession and worshiping in a male-dominated faith have led her to wonder if perhaps therein lies the problem: She’s not the rabbi’s son.

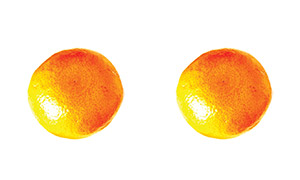

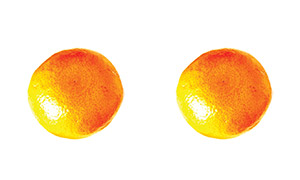

Susannah Herschel popularized oranges on the seder plate to symbolize LGBTQ+ acceptance in Judaism.

I first met Susannah Heschel in person as she prepared a Shabbat meal for guests in the kitchen of her Newton, Massachusetts home. Dressed for comfort and cooking, she nonetheless looked glamorous, with her trademark turquoise eyeshadow, stylish spectacles and aquamarine collar necklace. A glass baking dish piled high with chicken, fennel and clementines was ready to slide into the oven, but she was in a panic. She had just learned there were more vegetarians than expected, and she didn’t want them to go hungry or feel excluded.

She chopped broccoli while dictating replies to a constant stream of text messages. Soon, her phone started chiming a countdown to candle-lighting time. After kindling the flames, Heschel disappeared briefly, then descended the stairs wearing a regal purple velvet coat with pink flowers that she had bought at a favorite boutique outside Zurich, where she had recently received an honorary doctorate.

She selected a wide-brimmed hat from the stack she keeps by the piano in the living room before setting off for shul, one of the three Orthodox synagogues within walking distance of her home.

Heschel embodies many contradictions and embraces them because they’re honest parts of who she is, past and present. She is committed to carrying on her family’s legacy and she sees nothing incongruous about her feminism and choosing to pray at an Orthodox shul where she sits separately from the men. “I don’t think the separation of men and women is the foundation stone of sexism,” she says. “I’ve seen plenty of sexism where men and women sit together, even sexism in synagogues where the rabbi is a woman.”

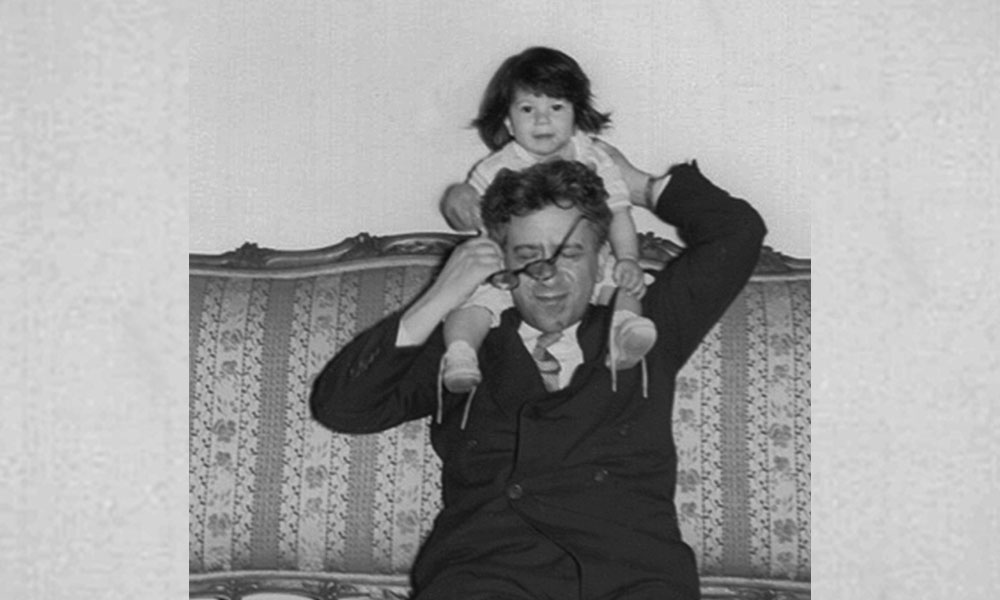

Abraham Joshua and Susannah Heschel. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Susannah Heschel)

Her father similarly eschewed labels and expectations. Born in 1907 and raised in a Hasidic enclave of Warsaw, Poland, Abraham Joshua Heschel grew up immersed in Torah, Talmud and classical Hasidic teachings. Founded by Jewish mystics, Hasidism is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that recognizes the miracle of God’s presence in everything, everyone, everywhere; Heschel, who was descended from Polish Hasidic dynasties on both his mother’s and his father’s sides, soon sought to inject that sense of wonder and abiding awareness of God into the modern world. At 20, already an ordained rabbi, he left Poland to attend the University of Berlin, where he studied in both traditional Orthodox and liberal Jewish circles. He was drawn to the poetic witness and timeless wisdom of the biblical prophets. In December 1932, weeks before the dawn of the Third Reich, he completed his doctoral dissertation, which was essentially a critique and course correction of Protestant Christian scholarship on the prophets. As part of a broader attack on Jews and their influence in German culture, prominent Protestant scholars had dismissed the passion and fervor of the prophets as madness. Heschel’s scholarship aimed to redeem them by casting them in a novel light: He saw the prophets as direct messengers of God, bewailing society’s ills and calling on humanity to rectify injustice.

With Hitler in power, the situation for Jews in Europe deteriorated. Heschel took a job at a Jewish institute in Frankfurt, where he succeeded the world-renowned Austrian Jewish philosopher Martin Buber. But two weeks before Kristallnacht, Gestapo agents arrested him in his home and deported him to the German-Polish border. Six weeks before the Nazi invasion of Poland, the president of Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati was able to secure visas for some Jewish scholars, including Heschel, to leave Europe. The young rabbi had no choice but to leave his mother and siblings behind. Some brothers would get out, but the Nazis would murder his mother and three sisters. (He had lost his father at the age of nine to influenza.)

When Heschel arrived in the United States, he was appalled by the indifference toward Hitler and Nazism. “I was a stranger in this country,” he later said. “My words had no power. When I did speak, they shouted me down. They called me a mystic, unrealistic. I had no influence on leaders of American Jewry.”

That apathy would have a profound effect on his activism and his writing, in which he tried to wake up complacent American Jews to their responsibility. The books he went on to write illuminated the partnership between God and human beings and explored how to tap into what God asks of us, often employing poetic language to get his point across. “Wonder alone is the compass that may direct us to the pole of meaning,” he wrote in Man Is Not Alone, published in 1951. That same year he would also capture public imagination with his book The Sabbath, describing the day of rest as “a palace in time with a kingdom for all.” The “Sabbath is the presence of God in the world, open to the soul of man,” he wrote.

Along the way he met and married Sylvia Straus, a concert pianist and music teacher. Susannah Heschel notes that many books about her father leave out her mother’s essential supporting role and the fact that the early years of their marriage were his most prolific. Straus, who died in 2007, first met Heschel in Cincinnati when he was at Hebrew Union College. They reconnected years later in New York after he became a professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS). Instead of an engagement ring, the rabbi gave his fiancée the grand piano that sits today in their daughter’s living room. Straus would play the piano for hours while her husband, ensconced in his study, pored over his books.

Susannah Heschel was born in the early 1950s (following her mother’s example, she never reveals her precise age) and remembers her father’s unbridled enthusiasm and support. When she walked into the room, he would drop his pen for a game or a hug. Raised in a high-rise apartment on New York City’s Upper West Side, Susannah read The New York Times every morning over breakfast with her father before heading east to Ramaz, a Modern Orthodox Jewish day school, and later Dalton, a progressive private school, both on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The bedtime stories her father told her were from the Torah and the midrash. Later, when she heard them again at school, she couldn’t understand why the other students sat in suspense, since she had heard them all before.

Occasionally, when her father returned home from teaching ethics and mysticism at JTS, she would surprise him in the coat closet, and they would play hide-and-seek. He also taught her how to play chess and Chinese checkers. On her days off from school, she often met him for lunch at the cafeteria inside the seminary, or outside in the late afternoons to keep him company on his walk home. He was always there for help with history homework and for comfort. “He was the person I would turn to if I had an argument with a friend and I was upset,” she recalls. “I didn’t want to wear glasses, so he said, ‘I will buy you contact lenses.’ He was always sympathetic. He also understood me.” Kindling the lights for Shabbat was always a highlight of the week. Heschel recalls how after her father would bless her, they would sit in the living room and watch the sun slowly descend over the Hudson River.

Classic Hasidic teaching infused her childhood. She remembers once, when she was young, her father pointed to a shelf full of Hasidic texts, and told her it was her inheritance. The civil rights era infused her adolescence. She was 12 when her father kissed her goodbye and flew to Selma to march with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. She worried he would not survive, after previous marches had led to bloodshed, but he returned unharmed. Her teen years were imbued with the teachings of the Hebrew Bible. She continued to develop an appreciation for how it spoke to the moral issues of the time. During her freshman year at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, she enrolled in a seminar on the Hebrew Bible and spent hours preparing for each class, devouring the texts. She recalls weeping over the passage in Deuteronomy where Moses dies. “My heart and my mind were both in that class,” she says. Like her father, she could not understand why biblical scholars attributed repetition and unusual turns of phrase to just scribal errors and nonsense. “They were missing the beauty of the text, the aesthetics. They were missing the literary quality, the metaphors, and the question of why this book has inspired billions of people,” she says.

On December 23, 1972, Heschel was home on winter break when she woke to her mother’s screams. Rabbi Heschel had died in his sleep at age 65. With her father gone, she continued her studies at Harvard Divinity School and the University of Pennsylvania and set out to answer the question that had perplexed them both—why did so many scholars slight the value of the Bible’s prose and underrate the power of its poetry? Her quest led her back to 19th-century Germany, where biblical scholarship had developed against a backdrop of rising antisemitism and the institutional exclusion of Jews. Heschel discovered instances where Protestant Christian scholars had twisted the words of the Talmud and Hebrew Bible to denigrate Jews—a foundation of contempt that made claims of scribal errors and gibberish seem minor.

Her doctoral dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania, completed in 1989, examined the German rabbi Abraham Geiger’s efforts to change this. Geiger, best known as a founder of Reform Judaism, initially tried to convince Protestant biblical scholars to consider the role of Judaism in the development of Christianity and study the Hebrew Bible in that larger context. But Jews had no standing in European academia.

Antisemitism kept Geiger out of theological journals and professorships just because he was Jewish. Heschel’s own challenges as one of very few women in religious studies at that time, coupled with her knowledge of feminist theory and the power of patriarchy, helped her grasp the weight of Christian hegemony on German academia of his era and the courage required to confront it. She combed through Geiger’s letters to friends, in which he expressed both sadness and optimism that theologians some day would see the errors in their interpretation and come to appreciate what Judaism offered to the world. That emotional and spiritual strength was something Heschel could not ignore. “That touched my heart, because it’s so easy to despair and get frustrated or angry, and yet Geiger was calm and assured,” she says. “I learned from him not only academic things. I learned from him something about menschlichkeit, how to be a person in this world.” She adds with a chuckle: “He was, of course, completely sexist. I think if I had lived in his day we would not have gotten along too well.”

Heschel landed her first teaching post in 1988, at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. After three years, she left for Case Western Reserve University in her mother’s hometown of Cleveland, “the greatest Jewish community I’ve ever experienced in my life,” she says. She fondly recalls the kosher butcher, a former teacher at a Jewish day school, who taught customers a piece of Torah while wrapping their poultry. She can still taste the challah from Unger’s Kosher Bakery and Food and misses shopping in Simcha’s Spectacular, a boutique that specializes in tzniut clothing, the modest attire that Jewish law prescribes for Orthodox women. But her most indelible memory is of the tiny Hasidic storefront shul around the corner from her home. Run by Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union, the two-room shul, which doubled as a kosher food pantry, would dole out plastic bowls of cholent ladled from a Crock-Pot after Shabbat services. “To me, it was the quintessence of Judaism,” she says. “It’s the modesty, the devotion, the care for other people, the piety, the delicacy. This is what you do. You get up from davening and you do a mitzvah for somebody.” She continued: “I have 350 students taking modern Jewish history—students from all over the world. When they go home to wherever they live—China, Brazil, Vietnam—and someone asks them, ‘Who are these Jews? What is Jewish?’…This is it.”

In 1992, Heschel was invited to speak at a United Nations Parliamentary Earth Summit in Brazil alongside other religious leaders, including the Dalai Lama. (Unable to resist, she slipped His Holiness a note asking when he would be reincarnated as a woman. In due time, he told her.) She returned to Cleveland ready to offer a course on religion and the environment. Colleagues pointed her to James Aronson, an acclaimed geologist from Texas best known for being the first to calculate the age of the oldest known human ancestor, a 3.2-million-year-old skeletal fossil nicknamed Lucy. When they finally met, Aronson, an intrepid world explorer, was enamored. A short time later, he came by her office to share one of his favorite quotations about religion and the environment. He had no idea it was a quote from her father. By the time the religion scholar and the earth scientist married in 1995—“A union of heaven and earth,” Aronson recounts with a smile—he understood he was becoming part of the Heschel dynasty. He offered to take her name, but she declined. The fact that he offered was enough to show her she had chosen well. They now have two college-age daughters, Avigael Natania Mira, named for Heschel’s and Aronson’s fathers and a cousin, and Gittel Esther Devorah, named for her father’s three sisters murdered in the Holocaust.

Heschel’s and Aronson’s wedding, held in New York, recreated a Hasidic celebration in Poland at the turn of the century. Musicians played only music composed at that time and men and women sat separately. Instead of flowers, the bride carried a book from the Apter Rav, the founder of the Hasidic dynasty from which all Heschels descend. Aronson wore her father’s black hat. Relatives led a kel maleh rachamim, or funeral prayer, in honor of the bride and groom’s fathers. Her cousins sang a nigun, a mystical musical prayer passed down from the Apter Rav. The ceremony was meaningful, modest, and members of her family who would not have attended a Reform wedding made a point of being there.

“People who write about my father don’t understand how close he was, and I am, to our Hasidic family. They don’t want to know,” Heschel says. She believes scholars often ignore how much a person’s family and home life shape his or her contributions to the world. “People are enmeshed in their families,” she says. “You carry your parents with you, in your mind, in your dreams, in your heart, in your feelings and your day-to-day living.”

Heschel’s most significant critique of scholarship on her father’s legacy, however, is that Black theologians are largely left out of it. He was close to King as well as to other Black clergymen such as Andrew Young, Bayard Rustin and C.T. Vivian. In fact, she says, there was a symbiotic relationship between her father and King, and the two men inspired each other. Stirred by the nascent civil rights movement around him, her father returned to his 30-year-old dissertation about the prophets of the Hebrew Bible, revised and expanded it, and turned it into a book. In the volume, published in 1962 as The Prophets, he argued that Isaiah’s verse about beating swords into plowshares offers a timeless denunciation of man’s romance with war. “The sword is not only the source of security,” he wrote, “it is also the symbol of honor and glory; it is bliss and song.” And he affirmed Habakkuk’s warnings that war is futile. “What is the ultimate profit of all the arms, alliances, and victories? Destruction, agony, death.” He pointed out the prophets’ persistent warnings about the dangers of authority. “The hunger of the powerful knows no satiety; the appetite grows on what it feeds. Power exalts itself and is incapable of yielding to any transcendent judgment,” Heschel wrote.

Abraham Joshua Heschel (second from right) in the 1965 civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery. Martin Luther King Jr. is fourth from right. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

What is often overlooked, his daughter says, is how her father’s innovative understanding of the Hebrew prophets enhanced Martin Luther King, Jr.’s calls for justice. King’s copy of the book, civil rights leaders have told her, was well-worn and replete with underlined passages, and King spoke as if he had memorized every word. Other civil rights leaders have confided that they kept paperback copies of The Prophets in their back pockets. “To omit entirely Black theologians who were in exactly the same position, speaking from the margins, and also imbued with the prophetic spirit, for whom the prophets are central, then what does that mean?” Heschel asks. “My father’s biographers are putting him in the wrong framework, and they’re neglecting what is an important framework.”

In fact, she says, her father felt an affinity with his African American Protestant colleagues that he shared with very few white Protestant or even white Jewish colleagues, some of whom considered him a poet rather than a serious scholar. Her father would say that if there is any hope for institutional Judaism in America, it could be found in the African-American church. There, he encountered a level of piety and religiosity that reminded him of the intense spiritual experience he had growing up in Warsaw, a level of piety he found missing in most synagogues.

Rabbi Heschel’s exegesis of the prophets endures in Black Protestant theology today. When asked at a recent lecture if anyone among evangelical Christians embodies the prophetic tradition, Susannah Heschel immediately pointed to the work of the Reverend Esau McCaulley, an assistant professor of New Testament at Wheaton College in Illinois. In his book Reading While Black, McCaulley advocates for what he calls “Black ecclesial interpretation,” a way to find hope by reading the Bible through the lens of the Black experience. “Jesus saw his ministry as a part of a tradition of Israel’s prophets who told the truth about unfaithfulness to God that manifested itself in the oppression of the disinherited,” McCaulley writes. “Jesus drew on the prophets as he spoke truth to power. Therefore, those Black Christians who see in those same prophets the warrant for their own public ministry have Jesus as their support.”

Heschel says there’s no question that her father felt the same way. Speaking truth to power was what he did, whether at a civil rights march or a dinner hosted by the Jewish Federation. To him, Judaism was a religion of dissent, grounded in the prophetic tradition. The margins were his home. Believing that American Jewry had lost its way, he wasn’t afraid to say so. That rebel spirit and penchant for ruffling feathers in his own community has been lost in the scholarship about him. “My father was a person who said what nobody else was saying and startled people because he was so different,” Heschel says. “And yet, what’s written about my father is very conventional, very ordinary. There’s nothing startling.”

Even as a father, Rabbi Heschel straddled conservative and progressive ideals; he held contradictory points of view, especially when it came to the role of women. Heschel recalls standing as a teenager on the sidelines of a Simchat Torah celebration where only men were dancing and singing with the Torah. When it was her father’s turn with the scrolls, he brought them to the edge and danced with her. At her request, her father arranged for a bat mitzvah, which was unheard of in Orthodox circles. For her 16th birthday, she asked for an aliyah, an opportunity to recite a blessing before the reading of the Torah, and her father found a Reconstructionist synagogue nearly 30 blocks away that would permit it. It was a long walk that Saturday. Sensing change on the horizon, Rabbi Heschel even encouraged his daughter to become a rabbi, going so far as to introduce her to the chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1972. Despite the introduction, the seminary rejected her request for an application. It did not ordain a woman until 13 years later. But he also told his daughter she would be a fantastic teacher. Not a scholar. A teacher. “I think he expected me to be a mommy. I would get married and have children and that’s it. I wasn’t supposed to be this,” she says. “I wasn’t supposed to be a professor or give public lectures or publish books. At most I was supposed to get a master’s degree to have something to fall back upon.”

Even as a father, Rabbi Heschel straddled conservative and progressive ideals; he held contradictory points of view, especially when it came to the role of women. Heschel recalls standing as a teenager on the sidelines of a Simchat Torah celebration where only men were dancing and singing with the Torah. When it was her father’s turn with the scrolls, he brought them to the edge and danced with her. At her request, her father arranged for a bat mitzvah, which was unheard of in Orthodox circles. For her 16th birthday, she asked for an aliyah, an opportunity to recite a blessing before the reading of the Torah, and her father found a Reconstructionist synagogue nearly 30 blocks away that would permit it. It was a long walk that Saturday. Sensing change on the horizon, Rabbi Heschel even encouraged his daughter to become a rabbi, going so far as to introduce her to the chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary in 1972. Despite the introduction, the seminary rejected her request for an application. It did not ordain a woman until 13 years later. But he also told his daughter she would be a fantastic teacher. Not a scholar. A teacher. “I think he expected me to be a mommy. I would get married and have children and that’s it. I wasn’t supposed to be this,” she says. “I wasn’t supposed to be a professor or give public lectures or publish books. At most I was supposed to get a master’s degree to have something to fall back upon.”

Before I met her in person and welcomed Shabbat in her home, I had met Heschel on a screen last spring while I was moderating one of the pandemic’s many virtual events—a conversation about her father’s legacy, a new compendium of his writings and a new documentary about his life. The other panelists, both men, invited me to call them by their first names. She asked to be called Dr. Heschel. “What is an issue for me is making sure that all women receive the credit and honor that men also receive,” she told me later. “If not more so, because it’s important for us to accept and acknowledge publicly what it has taken for us to reach this point.” Heschel is referring to a culture that she says still pervades even the most progressive houses of worship and academic circles. Too many scholars and religious leaders who embrace gender equality fail to look beyond structures and policies, she says. They neglect to take note when the rabbi calls up a man to recite kiddush and asks the woman to light the Sabbath candles. They overlook when male scholars are addressed by their honorifics but the female scholar in the same room is called Susannah. She calls this culture of unspoken expectation an “invisible mechitza,” referring to the partition used to separate men and women in Orthodox synagogues.

At the same time she was writing her dissertation and peeling oranges to revolutionize seders, Heschel was also editing an anthology called On Being a Jewish Feminist. Published in 1983, during what historians call the second wave of the feminist movement, it included essays by Jewish women on matters rarely, if ever, discussed in those days—domestic violence in the Jewish community, God as a she and Jewish lesbians.

Martin Luther King Jr. with Abraham Joshua Heschel during the Selma March in 1965. (Photo credit: Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture)

Author Laura Levitt, a professor of religion, Jewish studies and gender at Temple University, considers Heschel’s anthology “an early intervention” for women struggling to find their way in academia. “When we think of Jewish feminist studies in academia—important and iconic Jewish feminist thinkers—Susannah is one who has really built on some of the early work she’s done,” Levitt says, referring to the glass ceilings that Heschel has scratched, cracked and inspired others to shatter. The book led Heschel to become a mentor for dozens of women the world over, Jewish and otherwise, who call and email her for career advice or simply to thank her for pushing them to ignore the voices—both masculine and feminine—that hold them back. “She rode that second wave in a powerful way in the academic world and brought a lot of people with her,” Levitt says.

More recently, Heschel’s work has helped the women of Jewish academia’s #MeToo movement. In 2018, Keren McGinity, a research associate at the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute at Brandeis University, was the first woman to come forward with allegations of inappropriate behavior years earlier by a prominent gatekeeper of Jewish academia, Steven M. Cohen. A string of women then followed, echoing similar experiences dating back decades. Cohen was forced out of his tenured position at Hebrew Union College. McGinity, now a consultant on interfaith marriage for the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, was asked in 2020 to moderate a panel for the Association for Jewish Studies about the #MeToo movement.

Heschel participated in the panel, and McGinity listened as she described the ways men exclude women and why women stay silent. She also exposed the power plays that men use to threaten women’s professional abilities as “an attack on the mind.” For McGinity, Heschel’s words—“an attack on the mind”—crystallized how she felt about her experience. They helped her to finally fully grasp the ramifications of speaking out. “Listening to her was like an intellectual salve,” says McGinity of Heschel. “She’s helped me realize my own worth as a scholar and a Jewish feminist.”

Heschel believes that Jewish teachings can address the moral issues of the day. The world once again faces what her father called “a moral emergency,” with echoes of the antisemitism that he narrowly escaped. Amid the uncertainty created by the pandemic and threats to democracy, she believes Jewish scholarship has much to offer in a moment such as this, as the Jewish people have been confronting similar threats for centuries. “In many important ways, Jewish studies has shed a light on the failures of socialism, nationalism, fascism and so on,” she says. “For example, when nationalist movements are incapable of including Jews who lived in the country for 2,000 years, then that nationalism has a problem.”

Heschel believes that Jewish teachings can address the moral issues of the day. The world once again faces what her father called “a moral emergency,” with echoes of the antisemitism that he narrowly escaped. Amid the uncertainty created by the pandemic and threats to democracy, she believes Jewish scholarship has much to offer in a moment such as this, as the Jewish people have been confronting similar threats for centuries. “In many important ways, Jewish studies has shed a light on the failures of socialism, nationalism, fascism and so on,” she says. “For example, when nationalist movements are incapable of including Jews who lived in the country for 2,000 years, then that nationalism has a problem.”

Indeed, colleagues at Dartmouth, where Heschel and Aronson moved to teach in 1997, say Heschel has created a Jewish Studies department with a raison d’être of collaboration and integration. “We don’t see ourselves as siloed away in some corner of the university where Jews can take these courses and learn about Judaism,” says Shaul Magid, a scholar of Hasidism and Jewish studies professor. Heschel believes that the more Jewish studies becomes less exclusively Jewish and helps answer the larger questions posed by humanity, the more effective it will be.

Tarek El-Ariss, a professor of Middle Eastern Studies who co-taught a course with Heschel on the Jewish and Arab Enlightenment, says Heschel’s ethical commitment to knowledge shines through every interaction she has with students and faculty. Her goal of bringing a variety of voices to the fore, he says, creates space for students to understand that there are historic connections between peoples now portrayed as being in conflict. The fact that Jews historically have lived in harmony with their Muslim neighbors is an important part of the story, Heschel says. It doesn’t have to be us versus them, El-Ariss adds: “This is a project I know Abraham Heschel took to heart and is continuing with Susannah.”

Like her father, Heschel is not afraid to tread on sacred ground, as scholars must sometimes do to explain the past. For her 2010 book The Aryan Jesus, Heschel mined German archives to uncover the Nazis’ malign influence on Protestant theologians at German universities. Some conservative Protestants in Germany did not look kindly on her revelations that their predecessors had produced a Bible that labeled Jews as Satanists, Hitler as Christ and Jesus as a redeemer of the Aryan people. She also pushes for more honest and constructive interreligious conversations, challenging the motives and ethics of today’s discourse. It bears more than a footnote that around the same time that Rabbi Heschel was flying to Alabama to march in Selma, he also was jetting off to Rome to meet with Roman Catholic cardinals to discuss the Church’s teaching on deicide, the defamatory and antisemitic accusation that Jews killed Jesus. His diplomacy during the Second Vatican Council helped lead the cardinals to overturn that doctrine as well as the church’s mission for the conversion of the Jews.

But Heschel says that in the 50-plus years since, interreligious dialogue has grown stale, self-congratulatory and complacent.

Once again, she sees an opportunity to call upon the example of the biblical prophets. If religious leaders really want to effect change and move forward together, they would be wise to step aside and let modern-day prophets on the margins lead the charge.

Who are these prophets? She says that people who identify as people of color, nonbinary, LGBTQ—“those who keep the faith even when shut out, denigrated, even sexually abused”—have the clearest view. From the margins, they see through the fog of progress on the surface and identify the deep need for change. Jews, for example, must be willing to call out fellow Jews for their racism and misogyny just as they criticize people of other faiths for their antisemitism, she says. And the feminist critique of religion is one of the most important ethical challenges facing every religious community. “To do justice is what God demands of every man: It is the supreme commandment, and one that cannot be fulfilled vicariously,” her father told a crowd in Chicago on the day he first met Martin Luther King Jr. The rabbi’s daughter would say that God also demands justice of every woman. “I see feminism as being part of the prophetic tradition,” she says, “because it’s a movement about justice.”

Opening image: Susannah Heschel, Martin Luther King III, Arndrea Waters King and Bernice King on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in March 2022. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Susannah Heschel)

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.