Sign up for a webinar with the author on Tuesday, May 5 at 4:30 p.m. EST. Dina will talk about her search to unearth the details of her long-dead grandmother’s claims and the legal case she launched to reclaim the property.

Her family owned the building.

The Nazis took it away.

Now she wanted justice.

by Dina Gold

On the afternoon of December 4, 1990, following a night in a small hotel in what was then West Berlin, I hailed a cab and gave the driver the address: Krausenstrasse 17/18. As the cab left the prosperity of the Western sector, the apartment blocks, offices and even the people became grayer and grimmer, like a scene from a Cold War spy movie. We passed the remnants of the Berlin Wall, battered and covered in graffiti. Checkpoint Charlie was to my right as we drove into what had been, until only a year earlier, communist East Berlin. Off to one side was the area where Hitler’s bunker once was located. The cab turned a corner in the opposite direction and there, ahead of me, loomed a huge edifice. It looked even bigger because of the vacant lot beside it, the remains of one of the many buildings reduced to rubble by Allied bombing during World War II.

My cab stopped near the German flag flying at the front of the building, and I climbed out. Several large, gold plaques were on display on the wall outside the main entrance. One, in German, declared the address to be the Berlin outpost of the Federal Ministry of Transport, which at the time was still headquartered in Bonn. The afternoon was bitterly cold. Flurries of snow swirled about and left a light dusting on the Trabants—the East German-made cars—parked outside. It was 4 p.m. and daylight was fading. Workers were emerging from their offices and hurrying home.

Wrapped up in a red duffle coat with a hood, I forced back my fears and told myself, “I’m here and I have nothing to lose.” I marched through the double doors, across the marble entrance hall, and up to the receptionist—a heavy, middle-aged woman knitting inside a glass booth. I asked, in my imperfect German, if she spoke English. She looked back at me blankly and picked up a phone.

A few minutes later, a portly man in an ill-fitting brown suit appeared. He introduced himself as Herr Münch and asked what I wanted. I figured the worst that could happen now was that he would call the police and charge me with trespassing.

“I’ve come to claim my family’s building,” I told him.

Herr Münch looked nonplussed, perhaps even slightly amused.

“This building is owned by the German railways—what are you talking about?” he replied in a somewhat belligerent tone. With all the self-confidence I could muster, I delved into my coat pocket and took out the only evidence I had connecting me to this building.

“Take a look at this,” I said, and handed him a copy of the page from a 1920 German business directory with the listing, “H. Wolff, Berlin W8, Krausenstrasse 17/18.”

“H. Wolff—Herbert Wolff,” I told the man. “He was my grandfather.”

In truth, I was bluffing, as investigative reporters like me learn to do. I could show that my grandfather had been in the fur business and once had an office in that building—but I had nothing to prove that my family had actually owned the building. I believed we had, and my German-born grandmother, Nellie Wolff, had believed it; but, in a legal sense, I had nothing.

Still, my assertion of the name Wolff was enough to make Herr Münch turn pale. “You’d better come in,” he said. He led me through the security turnstile and down the long corridor that led to the staff canteen, where he asked me to wait while he went to telephone his superiors at the head office in Bonn.

After 20 minutes, Herr Münch returned. He beckoned me over, and we sat down at a small square table. Immediately, I detected a change. He grasped my hand and said, “I have spoken to head office. I know now that you are telling the truth. We have been waiting for this to happen. This place has always been known as the ‘Wolff Building’ but no one really knew why. Head office has just informed me that they knew this building was once owned by Jews, but the person I spoke to didn’t know if anyone had survived. Tell me your story.”

As I sat on a plastic chair in the canteen, I told Herr Münch the story of my family. When I finished, he said something I thought very brave for a longtime East German official: “Yes, you must get this building back for your mother.”

Touched by his decency, I confessed I had none of the official documents we would need to prove our ownership. “Oh, the documents exist,” he said. “You have to find them, but they exist.” Like all German bureaucrats, he knew about the German obsession for record keeping.

I left the building walking on air. Surely, Herr Münch was right and the records were somewhere. I would find them and justice would be done.

Left: An advertisement for H. Wolff furriers in the 1920 Deutsches Reichs-Adressbuch. Center: The cover of the H. Wolff catalog from 1910/11. Right: A 1910 photo of the back of the building from the 1910 edition of Blätter für Architektur und Kunsthandwerk in which the name “H. Wolff” is clearly visible. © Dina Gold

When I was a child growing up in London in the 1960s, Nellie, my maternal grandmother, used to take me to a patisserie opposite Harrods department store. Over coffee and cakes, which she could scarcely afford, she would reminisce about her life in pre-war Germany. She described a life of glamour and high culture, afforded to her by her husband, Herbert, my grandfather, and his family fur business.

Often Nellie would say, “Dina, when the Wall comes down, and we get back our building in Berlin, we’ll be rich!” I had no idea what she was talking about. Her story of an enormous, immensely valuable building that was rightfully ours was like a fairy tale. She might as well have been telling me about “Jack and the Beanstalk” or castles in Spain.

My mother, Aviva, born Annemarie, remembered the building. As a little girl of four or five, she would ride with her father, Herbert, and grandfather, Victor, on trips in the chauffeured Mercedes to the building, where she would go into the basement to jump up and down on the soft exotic furs stored there awaiting sale. “You can jump on the rabbit furs, but don’t you go jumping on the mink and sable,” her father would warn. But my mother always advised me to ignore Nellie’s tales. She believed that talk of ever being wealthy again and getting back the large office block in central Berlin was utter fantasy.

The world changed for my mother in 1933. That was the year Adolf Hitler took power and Nellie fled with her three children to British-controlled Palestine. Herbert had gone ahead to establish himself but squandered what money he brought with him through bad investments. The marriage soon fell apart, leaving Nellie to raise her children alone. To make ends meet, she opened a boarding house and luncheon service in Haifa for refugees and British officers. But she could never completely reconcile herself to her new life.

Nellie died in 1977. She never mentioned an address for the building and left no documents or photos. But in 1989, I believed it was time to find out if any of her stories were true. The Berlin Wall had come down and there was talk of the new, united Germany returning property stolen from thousands of Jews in East Germany.

My mother, however, had no desire to revisit her pre-war past. My father took a similarly negative view when I told him. “Grow up,” he said. “You can’t take on a government and win. Who do you think you are? You have a full-time job, a 14-month-old baby and a four-year-old; you just don’t have the time for this.” I understood my parents’ perspectives. But what if Nellie’s memories had been accurate and the family really had unjustly lost a property? That would mean my mother had been deprived of her inheritance and the Nazis had won! The moral imperative of finding out the truth drove me to decide that I simply could not walk away from my family’s history.

Fortunately, I had worked for many years as a BBC investigative reporter and producer, and I had learned the skills, and liked the challenge, of going in pursuit of a lead. My husband, Simon Henderson, was similarly undaunted: He had been based in Tehran for the Financial Times, covering the Iranian Revolution, the overthrow of the Shah and triumphant return of Ayatollah Khomeini, as well as the U.S. Embassy hostage crisis. He understood the importance of finding out the truth of what had happened and unequivocally supported me.

So, in the summer of 1990, while preparing for the BBC’s coverage of the German elections, I travelled to Bonn, which was then still the capital of Germany. While there, I hired a German researcher to help our BBC team. I also asked if he could help me on a private quest. Could he find out anything about the company my grandfather had once owned?

Within days, the researcher located old copies of the 1920s business directory Deutsches Reichs-Adressbuch or “All-German Address Book,” the equivalent of the Yellow Pages. Looking at the volume for 1920, under the section Pelz [fur], he had found the entry I would brandish before Herr Münch:

H. Wolff

Berlin W8

Krausenstrasse 17/18

Anfertigung feiner Pelzwaren [Maker of fine fur products]

Bingo! This was almost certainly the building Nellie had dreamed of recapturing.

I quickly amassed more information. The Wolff family fur business was founded in 1850 by my great-great-grandfather Heimann. But it was his son, Victor, who guided the company to international success, with buyers circling the globe acquiring pelts and agents with offices in London, Paris, Palermo, Copenhagen and even Melbourne. In 1908, Victor bought a large plot of land in central Berlin in an area of many Jewish companies and shops. He hired a top architect of the day, Friedrich Kristeller, to design the new headquarters for the H. Wolff fur company. When completed, the building, at Krausenstrasse 17/18, stretched back a whole block.

It was six stories high, with two large interior courtyards and beautifully sculpted stone carvings above the arched entrance. Emblazoned on the wall by the main entrance were the words, H. Wolff Konfektion feiner Pelzwaren, which translates as “H. Wolff Readymade Garments and Fine Fur Products.” Inside, the main entrance hall had marble flooring, carved wooden ceilings and mirrored walls, suggesting that no expense was spared.

Eventually, I even came across photographs of models wearing the many styles available, which paid testament to the luxury fur coats produced by the company in the early 1900s. Victor was at the top of his trade and recognized by the city of Berlin, which bestowed on him in 1912 the honorary title Kommerzienrat, designating him as a distinguished businessman.

Left: Gold and her grandmother Nellie Wolff outside the British Museum in London in 1969, © Dina Gold. Right: Gold and her husband Simon Henderson review legal documents relating to the claim with her mother Aviva Gold in 1992, © David Secombe.

Once I had some evidence, my mother agreed to pursue the claim. But time was short. Many people were applying for restitution at the time, and the German government had announced a deadline for claims. After that, any potential claimants would be presumed dead or not interested. When my mother wrote to the lawyer who would eventually take the case, he responded, “Is there reason to believe that this house actually belonged to your father’s firm and they were not just renting it?” But he did take our case, designated Claim 25823. My spirits sank, however, when he reported that some 150,000 claims had been registered with the government, and only 800 were currently being examined.

Meanwhile, we worked on establishing the line of inheritance. My mother would have to provide copies of her birth certificate, her parents’ marriage and death certificates, relevant wills and other official documents. She feared that the documents we needed had not survived the Allied bombing of Berlin during the war. At one point, my mother phoned the district court in the Berlin suburb of Charlottenburg and, in her impeccable German, asked the woman who answered if it would be possible to obtain the will of Victor’s wife, her grandmother Lucie Wolff, who died on February 25, 1932. To her astonishment, the woman calmly replied, “Would you like to stay on the line or would you like to phone back in ten minutes?” My mother said she’d call back. Ten minutes later, she rang again. “Yes, I have the will of Lucie Wolff,” the woman said nonchalantly. My mother was staggered. “Would it be possible to have a photocopy?” she asked. “Certainly,” the woman replied, “I’ll mail it to you.” Despite intensive bombing by the Allied forces, these German records had miraculously survived. That fact moved my father, proud of his RAF service during the war, to comment, “Obviously, we didn’t bomb them enough!”

In 1991, I learned that a New York property mogul had hired an East Berlin lawyer to track down the land registry documents of Krausenstrasse 17/18, as well as several other properties. The speculator apparently wanted to put in an offer to buy and renovate the building. If there were any truth to that possibility, we needed to act fast.

On a visit to Berlin, armed only with the telephone number of the lawyer, Simon and I called and said we wanted to meet him to talk about Krausenstrasse 17/18. He reluctantly gave us his address. We jumped in a taxi and drove deeper and deeper into the increasingly dingy, forbidding suburbs of East Berlin. When the driver finally stopped outside a big, ugly tenement block, we got out of the taxi with considerable trepidation. There was no elevator, so we staggered up several flights of stairs, passing rubbish strewn everywhere, wondering what on earth we had got ourselves into.

Breathless from our steep climb, we reached the apartment, knocked on the door, and waited nervously. A hostile-looking young man opened the door and demanded to know what this was all about. An awkward discussion ensued because our German was poor and his English was borderline non-existent. Somehow, we managed to convey our request to be shown whatever documents he had relating to the Krausenstrasse 17/18 building.

The young lawyer showed us a notarized copy of the Grundbuch—the land registry document—for Krausenstrasse 17/18, bound with an official-looking clip and bearing an equally official-looking embossed purple stamp. It was clear that he saw value in these documents and wanted to make some money from them.

Simon abruptly said, “How much?” The man, startled to be asked straight out what amount would close the deal, responded by holding up three fingers and saying, “dreihundert Deutsche Mark.” That was 300 Deutsche Marks, or about $200 at the time. Simon surprised him by whipping out his wallet, extracting three 100 Deutsche Mark notes and handing them over. The deal was done.

Before our new acquaintance had time for second thoughts, we grabbed the Grundbuch and exited the shabby apartment as fast as we could. Soon, we were safe inside a cab heading back to our hotel, where we finally had a chance to examine our purchase. What we found was startling.

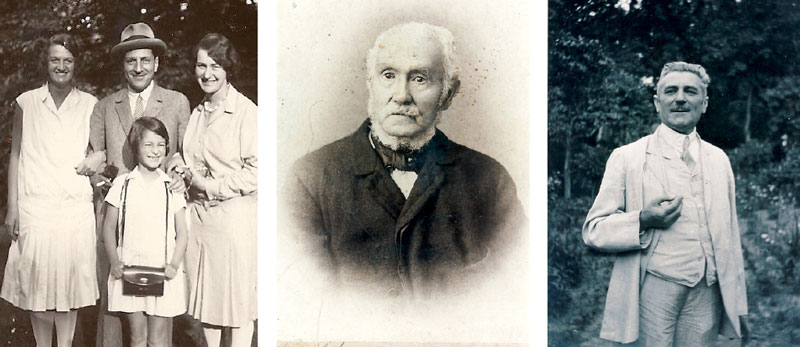

Left: English nanny Marion Teasdale with Herbert, Nellie and Annemarie (Aviva) Wolff in Berlin before they fled to Palestine. Center: Heimann Wolff, founder of H. Wolff furriers. Right: His son, Victor Wolff, who bought the land at Krausenstrasse 17/18 and had the building constructed. © Dina Gold

Even with our rudimentary knowledge of German, it was clear from the document that for years the Wolff family had obtained an apparently standard mortgage from the Victoria Insurance Company. But, according to the Grundbuch, in June 1937, the building changed hands because the mortgage had been withdrawn. The Victoria Insurance Company never took ownership. The building passed directly from the Wolff family to the new owner, the Reichsbahn, the German Railways.

This was the first hint we uncovered that supported the theory that the Victoria Insurance Company, one of the largest insurance companies of the time, and one that had many Jewish customers until it came under Nazi influence, worked in concert with Hitler’s government to seize the building and pay a mere pittance to the owner. (All of the people who had firsthand knowledge of the 1937 legal proceedings that handed our building to the Nazis—Herbert, his brother Fritz, the lawyers—were dead or their whereabouts unknown.)

A short, one-page letter attached to the Grundbuch, dated November 30, 1948, also encouraged us. After the war, the building was in the Soviet zone of occupation. Its ownership had, according to the document, been re-registered as the Deutsche Treuhandstelle, or (East) German Trust Authority.

Although the letter attached to the document was in German, we knew it carried a significance that would ultimately assist our claim:

…da der jüdische Vorbesitzer gezwungen war das Grundstück unter dem Druck der damaligen politischen Verhältnisse zu veräussern … Wir bitten Sie, sich jeder Verfügung über das Grundstück zu enthalten.

While neither Simon nor I could read or understand much German, we could certainly translate the word “jüdische”—Jewish. We couldn’t understand the rest of the sentence, but we suspected it meant the Soviets knew the building had been stolen from Jews. Back in London, we obtained a translation:

The Jewish private owner was forced to sell because of the political circumstances of the time…we request that you do not make any disposition of this property.

We were elated. Much can be said about the evils of the Soviet Union, but in this case, its occupation forces had arrived at a judgment that was extremely helpful to us and potentially to others pursuing claims. In the case of Krausenstrasse 17/18, the Soviets had taken the view that in the 1930s, Krausenstrasse 17/18 had been a Jewish-owned building that had been forcibly sold to the Nazis. Although the property came to be used for the administration of the East German railways, this note was intended to prevent any further sale until the true ownership was established. If Soviet officials had recognized that fact, we hoped new Federal Republic of Germany officials would as well.

The pursuit of my mother’s claim was an emotional roller coaster. There were some dreadful disappointments as I tried to help the lawyers overcome the obstacles that kept cropping up. My mother sometimes felt the German government officials were deliberately procrastinating, perhaps in the hope that she would die before the case was settled. With that fear in mind, she added a codicil to her will. If she died before her case was settled, she wanted me to continue with the claim on her behalf.

Along the way, I met young Germans who were acutely conscious of their history and carried what seemed a burden of guilt about what their fathers and grandfathers had done. Many went out of their way to help me. I was able, because of my connections at the BBC and in the printed press, to generate publicity about my mother and her claim, which had the effect of focusing German officials’ minds on the case. Still, given the obstacles, I have no idea how most elderly survivors or ordinary claimants can pursue their claims unless they are rich enough to hire private investigators.

Although there is a presumption in German law that any property sale by Jews after the Nuremburg Laws of September 1935 was likely coerced, German bureaucrats were nevertheless reluctant to concede that this applied to the loss of Krausenstrasse 17/18 in 1937. They argued that the mortgage on the building provided by the Victoria Insurance Company was not being serviced, although I discovered letters from the Wolff family lawyers for the years 1935-1937 claiming the mortgage was secure despite the severe anti-Jewish discrimination. Another tack used against my mother’s claim was that the building had been renovated and joined internally to its next-door neighbor, Krausenstrasse 19/20, and that the two properties were now inseparable. But that argument soon worked in our favor because we discovered that the Reichsbahn had paid more per square foot for that building, which had been owned by non-Jews, than they had for the Wolff building. But still, the delays in dealing with our case went on.

Eventually, after more than five years, the German officials handling my mother’s case decided to settle rather than go to court. Notionally accepting that restitution was appropriate, they offered to buy the building, as it was needed for Ministry of Transport civil servants who would soon be relocating from Bonn to the newly re-established capital. Although we sometimes feared that the German authorities would press for just a token settlement, they did not. In 1996, to gain legal title to the building, the government paid the then-market price of 20 million Deutsche Mark, equivalent to $14 million, that my mother shared with her siblings.

Today, both the German and the European Union flags fly, but otherwise the exterior of Victor Wolff’s building looks remarkably similar to pre-war photographs. The German Federal Ministry of Transport still has offices there, and I often wonder if any of the civil servants working in them know the history of the building and that it resulted in one of the largest payouts made to a Jewish family.

Hopefully they soon will. In November 2013, I wrote to Peter Ramsauer, the then-minister of transport, to ask that a plaque be put on the front of the property. Six weeks later I received a reply back from one of his staff promising to “arrange for the plaque to be produced and affixed to the office building.”

Since then, however, management of the building has changed hands. So I emailed the Federal Agency for Real Estate, which now has responsibility for the property. The response I received on August 21, 2014 was, “We will review your request and inform you as soon as we have new information available.”

I am still waiting.

This story is based on Dina Gold’s Stolen Legacy: Nazi Theft and the Quest for Justice at Krausenstrasse 17/18, Berlin to be published in June by Ankerwycke, an imprint of the American Bar Association.

Pre-order the book on Amazon

17 thoughts on “Stolen Legacy”

Great story. I recently saw “Woman in Gold” and your story, while slightly less glorious, would make a fine documentary.

Exciting story! Congratulations Dina. I hope to read the book soon; here’s to Oxford 2012 and fond memories!

I was absolutely amazed by your story, beautifully written, well done for all the hard work involved. So thrilled to hear the result and I will order our book now.

So thrilled that it is finally finished and ready to go well done dina u worked so hard on it and kept your mom on her toes every day checking all the facts will certainly order a copy .

Congrats, Dina!!! So excited to read the book!

I had the pleasure of speaking with your mother regarding her past and her determination to overcome horrendous scenarios resonated with me. I now recognize a similar tenacity within your own story and admire you persisting with the courage of your convictions. I look forward to reading the book very soon.

Fascinating story, beautifully written.

Hanita

Wonderful story – and I am glad to see that you got reparation.

Concerning commemoration of your family: Why don’t you lay Stumbling-stones for them in front of the building? Please have a look at http://www.stolpersteine.eu/en/home/ – I am pretty sure that Gunter Demnig will love to do this for your family.

Best, Aaron

What an incredible story and outcome! So many would never start to take on such a task…let along continue to completion.

What happened to Project Heart?

Congratulations on your perseverance and successful result. Your story demonstrates the tremendous injustice your family experienced and serves as a example that truth can and does prevail. I look forward to the book.

Well done Dina. Didn’t realise all the time I was working. For you and you working so hard at the BBC , you were writing such an interesting book

Beautifully written and terrific research, congratulations Dina.

Congrats to Dina Gold for her work to get the resulting financial payout for her family. I am thinking about going after land and homes that might have been taken from relatives in Bavaria in the late 1930’s. My family also lost property in Prague, but those records might not exist.

Many Jewish families need to realize that there are still plenty of opportunities to recover financially what their ancestors lost….

I shared and tweeted this article – many more need to know about opportunities to regain what they should have owned all the time.

Marc

http://www.ellisonadvertising.com

Oy, it’s so important to get the money!!! It’s the most important thing in the world!

Great article.

Use of NON PLUSSED is wrong. The opposite of what you mean. Look it up.