Opinion | Inside the Republican Jewish Coalition

The 2018 midterm elections will test a still-fragile accord with Trump.

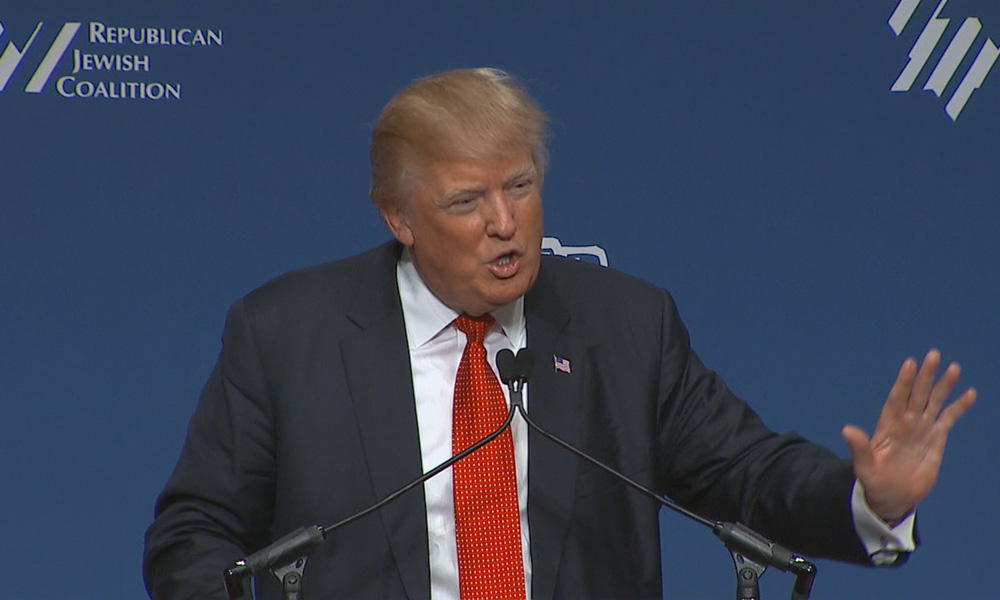

“You’re not going to support me, because I don’t want your money,” candidate Donald Trump famously told a gathering of the Republican Jewish Coalition (RJC) in December 2015. Delivering a speech laden with distasteful jokes about Jews and their alleged financial skills, Trump left the audience of bigwig Jewish Republican donors and activists uneasy. Few took him seriously, preferring Lindsey Graham, Marco Rubio, John Kasich or even Ted Cruz.

Fast-forward to spring 2018 and an email alert sent out by the RJC to its supporters. Thanking President Trump “for keeping your promises,” the alert urged members to send in a donation celebrating his first 500 days in office. Dozens of other RJC statements had already praised Trump, celebrating his policies and marveling at the steps he has taken in the Middle East.

Jewish Republicans, who comprise roughly a quarter of Jewish American voters, were almost torn apart by Trump’s ascendance to power. And the RJC had to navigate the gulf between those who could not fathom the idea of having Donald Trump as their candidate and those who bought into the Trump message. Now, however, they have all but coalesced behind the leader—some enthusiastically, others grudgingly.

What happened in the past two years to turn around so many Jewish Republicans? “There was Iran and there was Jerusalem,” responds one RJC board member, who still finds it hard to say a good word about the president’s personality, conduct or performance. “These are issues every Jewish Republican fought for. We can’t ignore what happened in the past year.”

Trump remains widely disliked in many Jewish Republican circles, including among RJC board members and donors. The RJC is still divided, but not in the apocalyptic way some had envisioned early on. The fault line is now between true believers (or, at least, early adopters) and those who might still feel queasy seeing Trump’s name on the ballot but appreciate many of his actions and are willing to provide as-passive-as-possible support. The early-adopter camp includes mega-donor Sheldon Adelson, who was critical of Trump early on but became his biggest supporter after exacting a pledge from Trump to move the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem. Another loyalist is Lew Eisenberg, a Goldman Sachs banker who served as the Republican National Committee’s finance chair during the election and was later rewarded by Trump with an ambassadorship to Italy.

Others in the Jewish Republican camp still have many reasons to dislike the president. His lack of experience in foreign policy and national security issues irks them. In conversations they point out his brash style, his associations with alt-right and outright anti-Semitic individuals, his offensive response to the Charlottesville neo-Nazi demonstration and his seeming lack of concern over rising anti-Semitism in America. They also note smaller kishkes issues: Trump refused to appoint a liaison to the Jewish community, as most of his predecessors have done; he has yet to fill the position of special envoy to combat anti-Semitism, despite repeated appeals by Jewish activists; he did not host a White House Passover seder or Jewish Heritage Month reception and, in general, is not hospitable to Jewish organizational leaders. On the other hand, Trump does keep in close touch with his types of Jews: donors such as Adelson, business buddies from his real estate days, media tycoons and, of course, his son-in-law.

For non-enthusiasts, the relationship with Trump is utilitarian: They provide him with cover from allegations of turning a blind eye to anti-Semitism, and he delivers on policy. The 2018 midterm elections, though, could test that practical consensus. The RJC is expected to pour more money into congressional races than in any previous cycle in an attempt to block a Democratic wave. Adelson, the RJC’s largest single donor, is also personally infusing $30 million into the Congressional Leadership Fund, though the full list of his endorsees is not yet clear.

But the elections, particularly the primaries, have forced the RJC into a potential clash with Trump over one specifically Jewish priority: the need to keep alt-right candidates at a distance from the Republican camp. Trump backed Corey Stewart, a candidate with ties to white supremacists, for the Senate nomination to run against Tim Kaine in Virginia; Stewart won the primary against an establishment-backed opponent. The RJC strongly opposed other GOP candidates affiliated with the alt-right, including Paul Nehlen in Wisconsin, Arthur Jones in Illinois and Patrick Little in California. (Little, an avowed neo-Nazi, finished 12th in the California Republican primary with 1.2 percent of the vote. Jones was unopposed but will almost certainly lose to the Democrat.)

The RJC has yet to make public a complete list of candidates it intends to support in 2018, but one early endorsement could signal the group’s focus. The RJC is pouring $530,000 into a major media buy in favor of Republican Brian Fitzpatrick, who is running in Pennsylvania’s 1st Congressional District—a newly drawn district that is considered a toss-up. This is an easy call for the RJC—Fitzpatrick’s rival, Democrat Scott Wallace, headed a fund that gave grants to pro-BDS movements. Blocking Wallace would be right up the RJC’s alley, allowing the group to maintain a focus on political candidates with special relevance to Israel and Jewish Americans.

And although the stakes for Republicans in the midterm elections are high, the outcome could also be pivotal for the RJC and the fate of Jewish Republicans. Waiting outside the camp, pitchforks in hand, are the Jewish never-Trumpers, people such as William Kristol, Eliot Cohen and David Frum who are not willing to accept Trump’s shortcomings as a price for his support for Israel’s right-wing government and other Middle East policies they believe in. Rather, they believe that every day Trump remains in office causes additional harm to America and to the party.

If the GOP fails in November and Democrats emerge victorious, those vocal opposition voices could have their I-told-you-so moment.

Nathan Guttman is a senior fellow at the Moment Institute.