In the previous issue, Moment asked David Dayen and Stuart M. Butler to debate whether there should be Medicare for All. Dayen said yes; Butler said no. Here, they respond to each other’s arguments. Read the first debate here.

Stuart M. Butler

David Dayen and I actually agree on most of the fundamentals. We agree there should be “affordable, adequate access to health care for everyone” (as I put it). We agree that people’s coverage should not depend on where they work, or whether they work—COVID-19 has underscored the need to move away from employment-based coverage. And we agree that the federal government—in other words, all of us taxpayers—should ensure that everyone can afford adequate care.

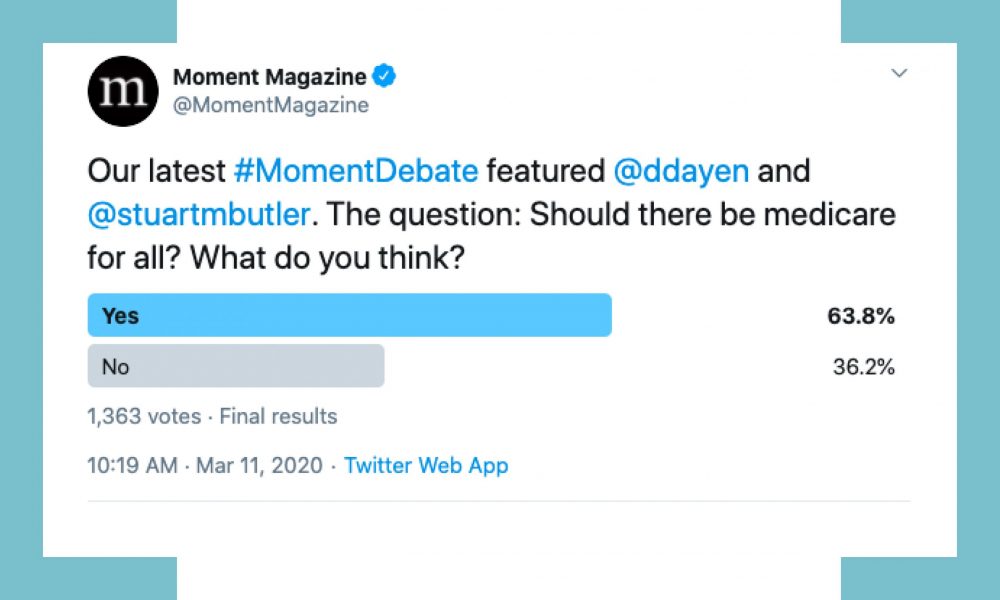

We asked Moment’s Twitter followers to weigh in. The majority said yes.

As I also said in my original piece, if David, Bernie Sanders and others were advocating the Medicare Advantage program for all, we could find agreement. In traditional Medicare, the government micromanages every detail, and enrollees can still be bankrupted by out-of-pocket costs. In the increasingly popular Medicare Advantage alternative, competing private plans receive a fixed budget for their members and have the incentive to keep them well. The plans must limit out-of-pocket costs, and they can now cover even non-medical items, such as transportation and nutrition. The plans have the flexibility to adjust provider payments and services, they are rated for quality, and enrollees can switch each year if they are dissatisfied.

I think we would have broad support for moving our system toward that version of Medicare for All. The Affordable Care Act exchanges offer private plans that have similarities to Medicare Advantage. Exchange plan enrollees receive income-based subsidies; those subsidies need improvement but are the right structure. I wish David and others would embrace that vision of Medicare for All—not the vision in which government bureaucracies set prices, decide what will be covered and what will not, and constantly fail to contain costs, and in which every major improvement in the program requires an act of Congress. If they would do that, then we could strike a deal.

Stuart M. Butler, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, directed the Center for Policy Innovation at the Heritage Foundation until 2014.

David Dayen

Stuart Butler argues that Medicare for All is a non-starter because the public won’t accept radical change. Well, like it or not, radical change is what they’re getting right now, with the coronavirus crisis. And better than any speech or sloganeering, it’s exposing the folly of tying health benefits to employment. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that close to 27 million Americans lost their health insurance between March 1 and May 2, because they or their family members were laid off from a job that provided health benefits. This is precisely the disruption that defenders of the status quo said would result from a shift to Medicare for All; actually, it was a hidden risk lurking in the system all along, just one economic crash away.

The catastrophe would be much worse without publicly provided Medicaid or publicly subsidized Obamacare exchanges. But private health insurance premiums could jump as much as 40 percent next year to offset coronavirus costs, a predictable consequence of an unsustainable for-profit sector. A system that puts tens of millions of people within one lost job of losing health coverage, and at the mercy of insurance executives, isn’t supportable. Critics of Medicare for All think they can get away with their criticism without comparing it to a broken status quo. The effect of the pandemic ends that fiction.

Butler offers some ideas worth exploring, such as global budgeting that would keep hospitals to a set amount of funding. But he ought to reckon with the core issue we’ve seen revealed since the coronavirus hit: Tying health care to employment doesn’t work. In every major country, guaranteed coverage with major intervention from the government does. Let’s finally get there in America.

David Dayen, executive editor of The American Prospect, is an award-winning author who writes about Medicare for All for numerous publications.