Foreign Affairs | Israel’s Complicated Dance with Putin

Since Russia invaded Ukraine, Israelis have scrambled to learn new steps.

Vladimir Putin has earned his reputation as a dictator, but he has often behaved warmly toward Jews. He has also maintained positive relations with Israel and made several trips there. The temperature dropped abruptly, though, with reports that the Kremlin was seeking to shut down the Russian branch of the Jewish Agency of Israel, the quasi-governmental organization that supports Jewish cultural programming and emigration to Israel.

Russian policy on Jewish emigration is often a proxy for other tensions, and right now there are plenty, some stemming from the war in Ukraine, others from Israel’s military activities in Syria, where Russia has a significant presence. Both Russia and Ukraine have substantial Jewish populations, and a group of rabbis in Moscow recently issued an unusual, carefully worded statement calling for peace in Ukraine and noting “a sense of fear and isolation not felt in decades.”

What’s going on, and how bad is it? To interpret these enigmatic signs, Moment turned to Aaron David Miller, a longtime Middle East analyst and negotiator who has served in both Democratic and Republican administrations and is now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

How serious is the downturn in relations between Russia and Israel?

The Ukraine invasion is one of the most consequential policy crises since the end of World War II, and it’s forcing the Israelis to confront some difficult realities. Since February, when Russia invaded Ukraine, the Israelis have been walking a tightrope. They understand that their interests on different issues regarding Russia are in conflict with one another. There are 1.2 million Russian-born Jews in Israel who vote as a bloc in Israeli elections. Israel also has Russians literally on its border, in Syria, where the relationship with Russia is crucial to maintaining Israel’s ability to enter Russian-controlled Syrian territory and strike Iranian targets.

The longer the Russia-Ukraine war continues, the greater the chance of deterioration in the relationship and the less flexibility the Israelis will have in balancing their interests in relation to Putin. I believe Putin will not completely undermine his relationship with Israel—it’s still very valuable to him—but the salad days are over.

Russian President Vladimir Putin visits Yad Vashem in Jerusalem in 2005. (Photo credit: www.kremlin.ru (CC by 4.0)

Wasn’t Putin supposed to be pro-Jews and pro-Israel? What happened?

Context is important with Putin. He’s not pro-Israel or pro-Jews. He’s pro-Putin and pro-Russia. Russian-Israeli relations, even at their best, were never driven by philosemitism. They’re part of Russia’s broader conception of its own interests, often vis-à-vis the United States—whether in the 1970s, when Brezhnev relaxed immigration policies on Soviet Jews to help obtain a deal to buy subsidized grain; or in the 1980s, when relations soured and the spigot of immigration dried up; or in the glasnost period when Mikhail Gorbachev was determined to solve the “Jewish question” by being supportive of Jewish emigration; or now, in the Putin era.

Until the invasion of Ukraine, the relationship under Putin had been quite productive. In 2005, Putin became the first Russian leader to visit Israel. He visited Yad Vashem, and he’s made multiple trips since then. In 2012, he supported the building of the Jewish Museum of Tolerance in Moscow. He was viewed as a philosemite. But we’re seeing now that when those positive relations aren’t viewed by Putin as being in Russia’s interest, they can take a turn for the worse.

Objectively speaking, the Israelis were extremely risk-averse for a long time in how far they would go toward supporting Ukraine. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky repeatedly asked Israel for military aid and did not get it. When Naftali Bennett was prime minister, he never used the words “Ukraine,” “Russia” and “condemn” in the same sentence. The Israelis have not participated in economic sanctions against Russia. You could say they’ve gone out of their way to appease Putin.

Bennett believed—wrongly, I would argue—that he could play a mediating role. He was treated as a sort of pawn. He thought he had pretty good contacts with both Zelensky and Putin; other than Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, he may have been the only leader to maintain working ties with both. He catered to Putin, some would say to a fault—it may be that he didn’t tend to his own coalition and it fell. When Yair Lapid took over as prime minister, all the risk-aversion evaporated and Lapid toughened up his rhetoric. Lapid, unlike Bennett, has not gone to great lengths to cater to Putin—not reaching out to him or meeting with him. It was Lapid who in April, as foreign minister, accused the Russians of committing war crimes in Kyiv, in Babyn Yar and in Bucha.

Was that when Putin moved against the Jewish Agency? Was there a connection?

Nobody knows for sure. It’s very fuzzy. Is what’s happening to the Jewish Agency the result only, or primarily, of events in Ukraine? The Russian Ministry of Justice accuses the office of violating Russian law, specifically by gathering information on Russian citizens, that is, Russian Jews. Apparently the ministry was upset because Israelis have maintained a data bank of such information in Israel.

Can the problems be sorted out? The Jewish Agency has been operating in Moscow since 1989. Since Putin came to power in 1999, there have certainly been issues from time to time, but in the past the Kremlin would intervene and any problems would be resolved quickly and out of the public eye. Now, the Russians seem determined to constrain, if not shut down, the work of the Jewish Agency; the Ministry of Justice actually has asked to liquidate the organization. So what changed? Maybe Lapid’s criticism did it; maybe Putin was unhappy about Israeli attacks in Syria.

But there are other factors you can’t rule out. One is brain drain. Hundreds of thousands of Russians leave the country every year; you can still leave the country freely if you’re a Russian citizen, so there’s no problem getting out. It’s possible that the Russians regard Jewish emigration as part of that broader problem. Since February, about 16,000 Russian citizens have registered as new immigrants in Israel—three times as many as in 2021. Another 30,000 have entered the country as tourists, possibly to stay. Among them are some very prominent citizens, such as Elena Bunina, the Jewish CEO of Yandex, Russia’s answer to Google. So this is a real issue and has created a lot of concern.

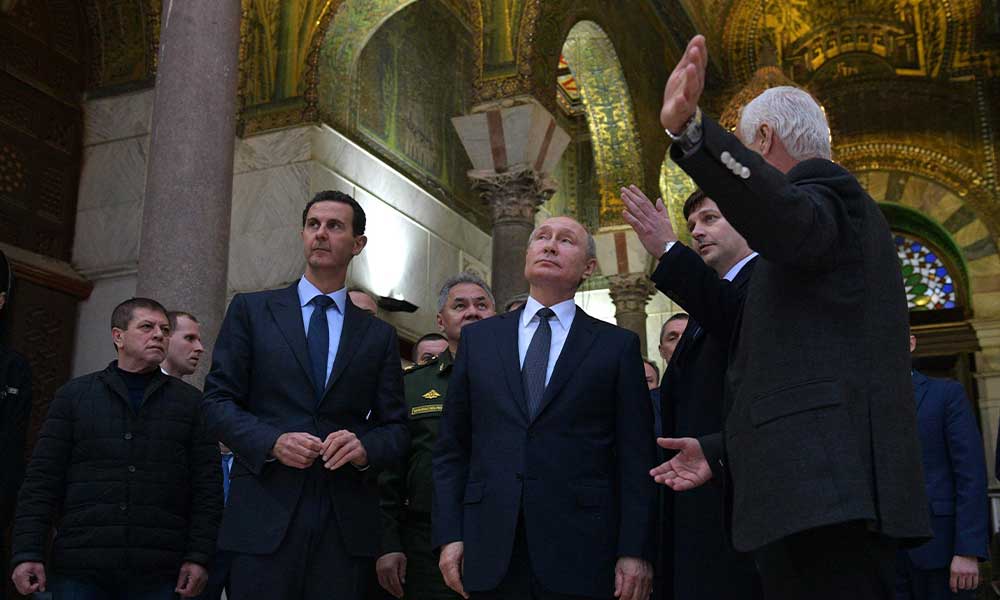

Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Great Mosque of Damascus with President of the Syrian Arab Republic Bashar al-Assad in 2020. (Photo credit: www.kremlin.ru (CC by 4.0)

It’s also possible that the Russians are cracking down generally on foreign entities that are identified with Western, liberal, democratic causes. That’s worrisome. The Jewish Agency case fits the pattern of using Russian Jews as pawns. There are still anywhere from 160,000 to 200,000 Jews in Russia proper. So far, Israeli government efforts to fix the problem have not been successful. But Israel is a serious country in an important part of the world; Russia envisions itself as a great power, and great powers have relationships with all important players. So we’ll see.

Is Putin’s relationship with Jewish oligarchs deteriorating?

Yes, but their being Jewish isn’t the main reason. It’s nonsectarian. There have been a series of mysterious deaths of Russian businessmen, Jewish and not Jewish. If you criticize Putin or undermine the war effort publicly, and if Putin or his intelligence services think you have influence within Russian civil society, you’re going to face consequences.

Has Israel responded to U.S. pressure to toughen up on Ukraine?

Maybe. I’m sure Bennett was making more than a few senior American officials unhappy. They may have expected more support from the Israelis, given that Israel is the region’s only democracy, America’s closest ally and also a country whose population has dealt with the aftereffects of genocide. Putin turned that genocide on its head in describing Zelensky, a Jew, as a Nazi. I think the Biden administration was unhappy about Israel’s lukewarm response, but there was a larger objective for the Biden administration in dealing with Israel during this period, and that was, “Thou shalt do nothing to bring about the collapse of this Israeli government” such that Netanyahu would return to power. The Biden administration gave Bennett an incredibly wide margin to maneuver on many different issues, including his relationship with Putin, because of this understandable concern. And it still shapes U.S. policy toward the Lapid government—witness the slow-walking of opening the Jerusalem consulate and the relatively mild criticism of settlement activities.

Are the Iran nuclear deal negotiations a factor?

Russia now needs Iran more than ever, and Iran’s supreme leader sent a message that Putin’s criticism of Israel was welcome in Tehran. This does not mean Putin is prepared to break relations and deny Israelis freedom of movement in the air over Syria, at least not yet. If there is no agreement to restrain Iran’s nuclear weapons aspirations, then I think we’ll see Israeli efforts to strike Iranian assets in Syria, and maybe in Lebanon. Given that Russian-Iranian relations are growing closer—in drone sales, for example—that set of circumstances could have consequences.

I don’t think Putin wants to go there, particularly when he has his hands full coping with sanctions and one war already. He is smart enough not to push the envelope. But is it conceivable that we could see something similar to what happened in 2018, when Syrian antiaircraft guns that were trying to strike Israeli aircraft shot down a Russian plane instead, and the Russians blamed the Israelis? That crisis got sorted out, but could there be direct Israeli-Russian confrontations, with Russians shooting down Israeli aircraft? I think it’s still very unlikely. The Israelis and Russians are in touch daily through hotlines, and they practice “deconfliction”—if the Israelis are going to strike somewhere, they send messages to the Russians to ensure no personnel are in the strike areas. But in the event of a serious Israeli-Iranian confrontation, anything could happen.

One thought on “Foreign Affairs | Israel’s Complicated Dance with Putin”

Isn’t the definition of moral clarity doing the right thing when it may harm your immediate interests? Isn’t that what we are asking of Russians when we want them to protest inside their own country in spite of the threat of imprisonment? It’s a little embarrassing that Israel can’t manage to have a bit more moral clarity in this situation.