Instead of counting sheep when I have difficulty sleeping, it’s become my habit to count and name the dead. The dead I am counting are mine—my family and friends, my romantic friends and a few others—along with one public figure who has always felt like part of my personal history. In counting them and naming them, I’m remembering who they were—and were to me. I’m recalling the me I was then—and am no more. I’m wishing that I had done this, and hadn’t done that, that I’d never been so young and so clueless. I’m learning some lessons I should have learned decades before. Counting and naming the dead has made me happy, sad, proud, embarrassed, angry and grateful. It hasn’t always provided a good night’s sleep. But I’ve found that there are benefits in counting the dead instead of counting sheep—in this process of love and regret and rueful remembrance.

The first two dead I count and name—I was in my teens when they died—are my mother’s difficult mother, Grandma Clara, and my up-to-then only president, FDR, over whom, to be perfectly honest, our family shed a lot more tears than we did for Clara. The reason I name Franklin Roosevelt and none of the other public heroes who died in my lifetime is that President Roosevelt (as I and so many Jews of my generation were raised to believe) knew us, understood us, cared about us—and in some undefined but encompassing way watched over us.

And I had proof! It was 1940 and Bunny, who lived next door to me, was eager to mail off some holiday cards she had written. But Bunny was only eight, and the nearest mailbox was three highly trafficked streets away, and her parents—despite much argument from a deeply disgruntled Bunny—wouldn’t let her walk there on her own. After she’d argued—and lost—her case, her father suggested, playfully I presume, that she take up the mailbox matter with President Roosevelt. And that was exactly what Bunny did, writing and mailing a letter straight to the top, seeking a solution to her problems with dangerous crossings and distant mailboxes. And not too long after her letter was sent, a new mailbox was installed—right down at the corner of our street.

Yes, FDR was benevolently watching over us. Grandma Clara, however, not so much. Indeed, the Clara I knew was a grouchy, testy fire hydrant of a woman, who lived with us for a while—a strenuous while—and who saw her role in our lives as complainer-in-chief and in-house critic, poor strategies for winning hearts and minds. And yet when I think of her now, when I lie in bed and name her name, I also remember the few things I knew about her: that she was widowed early; was left with no money, no skills and four young children to raise; was urged, but refused to give them up for adoption, and

somehow—how I wish that I had asked her how she’d done it—brought up her

daughters and sons to productive adulthood.

In naming the dead I am often troubled by questions I should have asked, questions that no one alive today can answer, questions that all of us should be asking the Claras in our lives before it’s too late. What was your life like when you were growing up? What did you think, or hope, your future would be? Why did you choose to marry the person you married? What was your biggest mistake? What accomplishments are you most proud of? What are some of your dearest memories? Everyone, even difficult grandmas, have stories they’d like to tell, stories it could enrich our lives to hear. Among my biggest regrets are all the stories I never heard because I never thought to ask the questions.

Death, however, was much on my mind when I was growing up, and I wrote about it in poems of fatal intensity, poems that featured dead parents, entire dead families, dead soldiers, dead dogs, and—in late adolescence—a near-dead me:

Death and desire crumpled in a corner.

And I in black, the solitary mourner.

Often finale but birth, thank God, more often.

And yet I think I know too well the coffin.

My parents, reading my writings, urged me to write poems less and ride my bike more.

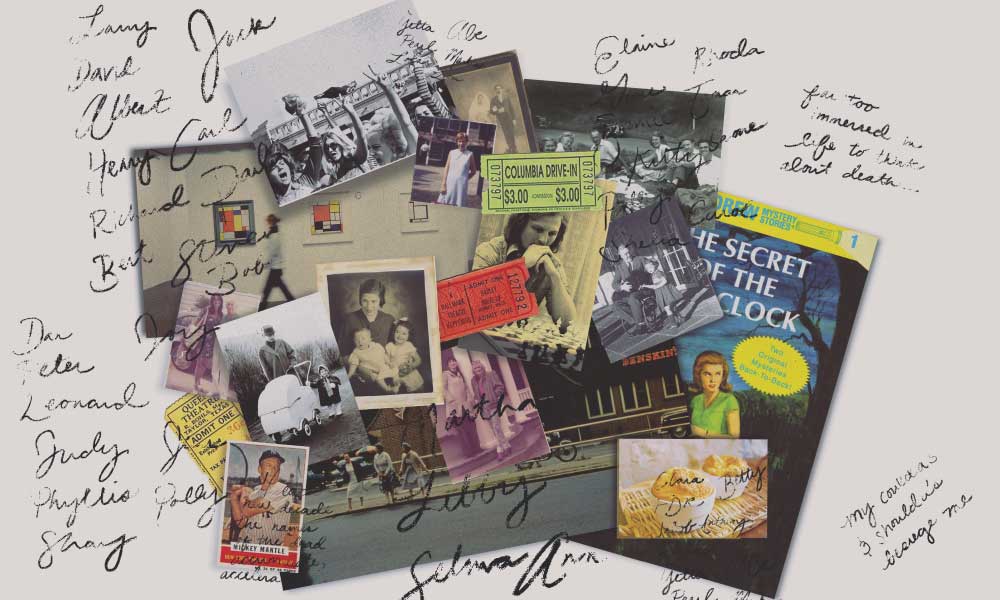

Judith Viorst’s grandparents, Clara and Nathan Ehrenkranz, on their wedding day. Date unknown. (Images courtesy of Judith Viorst; Wikimedia)

During my twenties I married and then divorced and then re-married, far too immersed in life to obsess about death, although I do remember telling a friend, whose grandfather had died, how lucky I felt to have made it through this decade without losing anybody I loved. I should have, but didn’t, knock on wood as superstition advises us to do when tempting fate with such provocative claims. But after what happened happened, I never ever failed to knock on wood again.

For when I was 29, my husband Milton and I had a baby, our first baby, a baby boy who was born too soon and perished after only two days on this earth. I never held him or touched him, attached as he was to assorted tubes and drips and machines. And when I name him at night, when I acknowledge the brief existence of Jacob Anthony, I offer an apology for not once having taken him into my arms.

There weren’t, and maybe still aren’t, any ceremonies or rituals to mark the life and death of born-too-soon babies. So all I could do for a while, quite a while, was talk about it and cry about it, to practically anyone who just said hello.

My first published writing on death was not one of my death-and-desire poems, but a children’s book called The Tenth Good Thing about Barney. I wrote it when Tony, our oldest, was eight, in the wake of a quite daunting conversation:

“Mommy,” Tony asked me one day, completely out of the blue, “am I going to die?”

“Everyone dies,” I said briskly, as some child-raising book had recommended I do. “But you won’t die for a very very long time.”

After a thoughtful pause, he came back with “But do I have to die?”

“Everyone dies and you will too,” I matter-of-factly repeated. “But not for a very

very”—and I grew firmer with every very—“very very very VERY long time.”

There was silence on the other end (while I prayed this would go away), after which Tony tearfully said to me, “Mommy, mommy, I don’t want to die.”

And I, not able to bear my son’s distress for another second, offered this desperate and utterly shameless reply: “Well,” I told him, “maybe they’ll invent something.”

After which I decided I needed some better answers on death—both for Tony and me.

In my Barney book, a little boy is mourning the death of his cat and finds solace in recounting good things about him: That Barney was brave and funny and smart and only once ate a bird, among several other—a total of nine—fine qualities. He is comforted, too, by learning that Barney, buried in the yard, will help grow the flowers, Barney’s tenth good thing and “a pretty nice job for a cat.”

Dealing with death through memories and through understanding we’re part of the cycle of nature, that nothing that’s part of nature is ever lost—not my last word on the subject, but surely a whole lot better than “maybe they’ll invent something.”

Over the decades, death became more frequent and more familiar, although sometimes still quite painfully premature.

I count my mother Ruth—a warm and much-beloved woman—whose heart gave out just short of age 63, who starred at tournament bridge and knew every lyric of every song, and whose love of books made a reader and writer of me, and whose glorious gift for friendship, suffused with good will and empathy, taught me all I needed to know about friendship. Wreathed in cigarette smoke as they chatted in our breakfast nook or sun parlor, telling her secrets they could be sure she’d keep, my mother’s Yetta and Pearl, and all the others she called “the girls,” became the sustaining context of her life.

None of these women, including my mother, worked outside the home. None of them aspired to a career. Most of them were smarter, stronger, more patient and better drivers than their husbands. But their job was to tend the house, raise the kids, have conjugal sex when required and do some do-good work as a volunteer. Most were the daughters of immigrants, and what they wanted above all else wasn’t passion, love, adventure or a Ph.D. in physics. It was security. (My mother’s sister, Florence, actually chose to get a Ph.D. in physics. But because she never married and had children, I was raised to believe that her life was a tragic failure.)

Security, as these women understood it, usually came from being someone’s wife. They also understood that in the world and time they lived in, men made the money and women made the life, which meant that their husbands earned enough to support them (without, thank God, their having to work) and had bought enough insurance to leave them what was called “well-fixed” in widowhood.

Although my mother died too soon to be a widow, her friends—enjoying their children, their grandkids, their card games, their swim clubs, their cruises and each other—knew how to have a merry widowhood.

Now maybe some of those Yettas and Pearls were women who harbored larger, grander ambitions. Maybe, as a feminist friend once suggested, marriage—for some—was where dreams went to die. Maybe, for the wife who lived on tranquilizers and the wife who saw a psychiatrist once a week, the price they paid for security was too high. And maybe it took me too long to consider the maybes.

My younger sister Lois, my only sibling, also died too soon to be a widow. As I name and think about Lois, I remember a blue-eyed blonde with a Daisy Mae body, in every way the opposite of me—outdoorsy, athletic, interested in science, bored with Nancy Drew and poetry, yearning to go to medical school but—since she wasn’t a boy and wouldn’t be working too long before she got married—pressed instead to become a lab technician.

Despite our differences, Lois always yearned to be my best friend. I always yearned to be an only child. But 20 months after my birth I had to share my mother and father with this cuddly, roly-poly baby sister. I’ve spent half my life writing reams about sibling rivalry. And in truth I wasn’t what you’d call the sweetest and kindest big sister in Northern New Jersey.

My sister had many gifts: The plants she planted always thrived; mine always withered. She was a gourmet cook, champion tennis player, great mom. But what I remember best is the remarkable strength and courage, the unyielding grace and dignity and calm with which she faced her dying and death at 50.

Judith Viorst (l) and sister Lois in Washington, D.C. 1980s. Ruth Stahl and her daughters, Lois (l) and Judith in the early 1930s in Newark, N.J. Viorst and her father, Martin Stahl, in the early 1970s in Maplewood, New Jersey.

On Saturday afternoons, when we were kids, my sister and I would go to the movies. For 25 cents apiece, we got quite a deal: Two feature films. A cartoon. A heart-stopping serial. The coming attractions. A news-of-the-week newsreel. And then the lights came on, and the theater held its popular weekly yo-yo contest, with boys and girls competing up on the stage. And though I never came close to winning a contest, I never—until an embarrassingly advanced age—went to that movie theater without my yo-yo.

And I never got through a movie where, if an animal—any animal—was hurt, my sister didn’t start sobbing noisily, requiring me to drag her out of her seat and into the lobby until she recovered. Untroubled by the massacres and mayhem afflicting the humans on the screen, she gave all her sympathy to the non-human creatures, invariably falling apart if a cowboy spurred his horse or a puppy’s paw was stepped on. Mopping her dripping eyes and nose, and furious that I was missing part of the movie, I’d reproach my sister for being so wimpy and weak. I never dreamed that one day, mopping my dripping eyes and nose, I’d speak at her funeral—and call her the bravest person I’d ever known.

One night when I couldn’t sleep, I got out of bed and queried Google on why this God I staunchly don’t believe in allows so much pain and suffering in the world. Google directed me to The Book of Job. And there, when the much-abused Job has finished setting forth his complaints, God chooses to answer his questions with more questions:

“Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?”

“Knowest thou the ordinances of heaven?”

“Will the unicorn be willing to serve thee?”

“Shall he that contendeth with the Almighty instruct him?”

Despite these reminders of my insignificance, and despite the fact that I staunchly don’t believe in Him, I find myself contendeth-ing a lot.

The next of my names is Abe, my 16-years-older-than-I first husband: My hero, my teacher, my major pain in the ass. Law professor until the dire days of McCarthyism. Eccentric delight of his legal philosophy class. Dabbler in Tarot cards and Jewish mysticism. Fervent fisherman of bluefish and bass. Unfaithful and contentious and impossible to live with, but a man who, after our quite uncontentious divorce, remained a dear and devoted friend until his untimely death at 62.

Abe had been fired from Rutgers Law School for taking the Fifth Amendment, as many brave people in many professions had done, rather than answer questions from congressional committees about their political affiliations. But after the 1950s, when the witch hunt had finally begun to run its course, and some universities started to offer apologies to the teachers they had fired, Abe hoped he too would receive some public acknowledgment of the damage that had been done to him. He died without receiving that acknowledgment.

But I, along with Milton, pursued the matter, sporadically prodding Rutgers on Abe’s behalf. And in 2009, more than half a century after I, a terrified 22-year-old, helplessly sat in a hearing room, watching as her husband’s career was destroyed, I held in my hands a letter—a heartfelt, beautiful, apologetic letter!—from the Chancellor of

Rutgers-Newark University. It expressed “profound regret” at what had been done to Abe and two other Rutgers professors. It spoke with pain and sorrow of the “mistakes that were made,” the “injustice” that had occurred. It called the firings “a blot upon our reputation.” And although it was 50 years later and although Abe had long been dead, justice—imperfect, delayed—had had the last word.

“We did it,” I sometimes say when, lying in bed and counting the dead, I speak Abe’s name.

And I smile when I count and name my father, Martin, on his own from my mother’s death until his late 80s, recalling I had to notify three different ladies in three different states that their boyfriend (past, present, potential) would no longer be available for phone conversations, or dinner, or…fooling around. In naming him, I’m remembering that my father loved women, loved ballroom dancing, loved golf, and hated the New York Yankees so passionately that, after his first heart attack, his doctor sternly told him that he could never watch the Yankees play again.

“Every time they win,” said Dr. F, “your blood pressure goes straight through the roof. You’re going to give yourself another coronary.”

I also remember my father’s unfailing embrace of his lifelong duties as an accountant, or—as he liked to remind us—a CPA, never deterred by bad health or bad weather conditions from showing up at the office every day. And although I always credited my bookish mother for turning me into a writer, it’s taken me much longer to see that what helped me become a deadline-meeting professional was my father’s

tush-on-the-seat-get-the-job-done work ethic.

With each new decade, the names of the dead accumulate, accelerate. I count the names of my in-laws, Betty and Lou, good decent people who guarded their pennies, cherished their only son, had little talent for playfulness or pleasure, and who once, when they came to visit us from New Jersey, stood at our front door weeping because, they explained, they’d have to go home in a couple of days.

I could have been, and should have been, and very much wish I had been, a more generous and more patient daughter-in-law.

As I count the dead, my coulda’s and shoulda’s besiege me: I should have sat with Clara and heard her stories. I should have held my baby before he died. I could have been a more welcoming sister to Lois and not been such a meanie when she cried. I could have invited my in-laws to please come inside and stay a whole week instead of a weekend. I could have made more room in my heart—and made more time in my life—for the people who came knocking at my door. I could have mustered more grace and more good humor as I barreled through my kids-career-marriage days. I could have treated my “To-Do” list as something less, far less, than a sacred document. And although I figured out some of this in time to mend my ways, the regrets I have to live with, I’ll have to live with.

I count and name the men—the romantic partners, the special friends—who powerfully shaped the contours of my life.

Larry, tender and earnest—my first love.

David, who said I had brains—and urged me to use them.

Albert and Henry and Jack and Carl and Richard and Paul and Bert, who

…introduced me to Mondrian and Picasso.

…taught me the proper way to eat an artichoke.

…switched me from Doris Day to movies with subtitles.

…insisted (wrongly) that I could learn to play chess.

…took me to several lectures on World Federalism.

…took me to several lectures on Sigmund Freud.

…and encouraged me to become a stop-the-war, civil rights, women’s rights and climate-change-is-for-real political woman, marching in protest marches, chanting at rallies, waving signs at demonstrations and picketing the White House (with one, then two and finally three little boys in tow). I even got arrested a couple of times.

I also count and name the married men who became my friends as part of a couple, and who, along with their wives, were the companions of our lives, Milton’s and

mine—friends we dined with, traveled with, went to movies and concerts with and celebrated life’s major milestones with:

…Steve and Dan, on-the-side-of-the-angels journalists.

…Bob, whose elegant legal mind I revered.

…Peter, a playful pediatric surgeon, who cheered up his worried young patients by greeting them dressed up in a gorilla suit.

…And Leonard, an activist rabbi, committed to social justice, world peace and Major League baseball, whose devoted congregation loudly and lovingly laid him to rest with a raucous rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

I believe that each of these men, in his own way, would have hurried to help me had I called for help. And although I can’t call on them anymore, I count them, and I name them, and I remember them.

And of course I count the women—my comforters, confidantes, gurus, playmates, soulmates, pals—without whom I’d have had an impoverished life: Two Judys, Phyllis, Shay, Joy and Elaine. Ruth C, Ruth G, Grace, Bonnie, Jean and Kitty. Plus Polly, Sheila, Rhoda, Tamar and Saone. Plus Carol and Martha and Libby and Selma-Ann. They were therapists, artists, writers, fashion designers, economists, social workers, lawyers, actors, political activists, educators. They were wives and mothers and grandmas and volunteers. In naming them, I remember our shared laughter, shared anxieties, shared tears; instructions for making a cheese soufflé, discussions about what’s going on “down there;” Kitty’s breathtaking brilliance; Shay’s ferocious independence; Phyllis’s awesome gift of empathy; Polly’s patient guidance through the terrors of early motherhood; Ruth G trying to teach the Twist to me. Our poetry group, our novels group, our lunch dates and walking dates and phone conversations. Our years and years of tea and sympathy. And our trusting revelations about our marriages, kids, insecurities, work and weight; about our transgressions, indiscretions, screwups—everything.

In religious memorial services, in Black Lives Matter shout-outs, on the anniversary of 9/11, in the news of how many the virus has killed today, there are many different ways, many different reasons, for us—the living—to count and name the dead. I do it because it allows me to honor their memory and our shared history. It deepens my understanding of who they were, what we meant to each other. It shows me what, even now, I might try to repair. It is, I suppose, the closest I get to prayer. And in its rue and regret, as well as in its sweet recollections, it enriches my life.

And one thing more.

As a lifelong nonbeliever, my version, my vision of immortality is being remembered by others after death. And although once people die, they’re likely to be in no condition to notice whether or not they’re being remembered, I count and name the dead

because—unreasonably, insistently, incorrigibly—I continue to believe they know I do.

What did you think of this story? Share your comments in a letter to our editors!

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

Oh my. I am not the only one who does this. I look in my address book, and almost each year there is one person less to call. But I’m with little Tony on the questions.

Judith Viorst, who has counted the decades and pointed the way for the rest of us since she realized “It’s Hard to be Hip Over Thirty,” once again brings us insights both poignant and funny. And as always, I can only say “Me too, Judith. And thank you!”

Wonderful article…tender, thoughtful and beautiful. May their memories be for a blessing❤️❤️

What a profoundly moving article, from an excellent writer who has touched and enriched the lives of so many of us! Judith Viorst is mishpacha to each of us, her losses mirror so many of our own and bring us to tears. May all of us be blessed with good health, long, joyous lives and wonderful memories which keep loved ones alive in our hearts and minds!

I sold children’s books for several years, and Ms Viorst”s book about Barney was invaluable to my co-workers for our grieving customers and for those whose kids simply had questions. Thank you, so much, for helping me reconnect to my late husband, Lawrence, union organizer, reader, radio show host and bookseller, who I met working at that bookshop: he was from Queens, and echoes of his voice and commitment to better working conditions for underpaid, diligent workers are reflected in the beautiful tone of this piece. And to my dear bookseller pal, Pat, whose author husband has recently passed away and joined her, wherever they both are. I say their names, and others, with mixed feelings including love and gratitude. Thank you so very much.

Phew,yes,THANK YOU‼️

thank you again for all yr wisdom & making me laugh & cry over the decades I have spent reading & rereading & sharing with friends especially my other fav. poet also Judith . We always waited each decade for your help in getting us through it with humor & irony She is not with me to share this & know she would’ve thought it sad but perfect.

What a lovely, meaningful, beautifully, wonderfully-written piece. I will send it on to my friends as soon as I finish writing this note of true appreciation!! Thank you so much! (I seem to remember first reading Judith Viorst in Ms. Magazine when it first came out – when I was a young, striving “Professional” – or so I thought.)

Thank you for all of your articles and books through the years. My first Judith Viorst article was in Redbook magazine, probably in the early 1970’s. It was about your little boys whose favorite game was, “Let’s see how far out we can climb out on a tree branch before it breaks” I was raising 2 boys who climbed a small tree at 18 months of age. I became your fan forever, because I could laugh and cry in recognition.

By your counting of “the dead,” you make them come alive for all of us to also enjoy and think about.

Thank you!

As I age, gracefully, I hope, I think more and more of the people I’ve lost along the way, the people who made me the person I am today and how I wish I could share my present, along with my past, with them. We are indeed a people of memory. Every time I say my son’s name, I am reminded of my mother, for whom he is named.

My husband is planning on concluding his upcoming virtual big birthday celebration with a poem by Judith Viorst.

Thanks for the memories!

Tender, heartfelt, moving, useful and just a darn good idea. I have 3 special people that I speak with whose pictures are in my bedroom and they make me feel warm and fuzzy for the love we shared and the memories I am lucky enough to have. I intend to expand my list because I think it is a brilliant way to remember all the people with whom I have shared my life. God is another question. I cannot fathom that a G_D set up some of the horrors people struggle through but I do ‘know’ there is energy. Energy creates and cannot be destroyed . Thank you for your contribution to my 83 year young life.

Judith is still a brilliant and extremely talented writer. I enjoyed this wonderful article and hope she continues writing for many years to come!