I’ve always loved being Jewish, but growing up, I felt lucky that my dad was Christian. Unlike many of my Jewish friends, every winter my sister and I had an excuse to decorate a tree, drive by ornately decorated houses and, of course, open the presents we actually wanted after the socks and pajamas we received on Hanukkah.

Although we participated only in secular Christmas traditions—so my dad could share a cherished part of his upbringing with us—I always felt a bit guilty for enjoying them. I was proud of my Jewish identity, even at a young age. So when friends would come over and find a Christmas tree in my house, I felt embarrassed. When I learned the term “Chrismukkah,” that changed.

What is Chrismukkah?

I was in high school when I first heard about Chrismukkah from a Jewish soccer teammate. While it’s sometimes used to name the rare occasion when one of the nights of Hanukkah falls on December 25—2024 happens to be one of them, and the first night at that—it broadly describes when Christmas and Hanukkah traditions are celebrated in combination, during the same season.

According to the Jewish Museum Berlin, the idea was first conceived by German Jews in the 19th century under the name “Weihnukkah” (a combination of Weihnachten, the German word for Christmas, and Hanukkah).

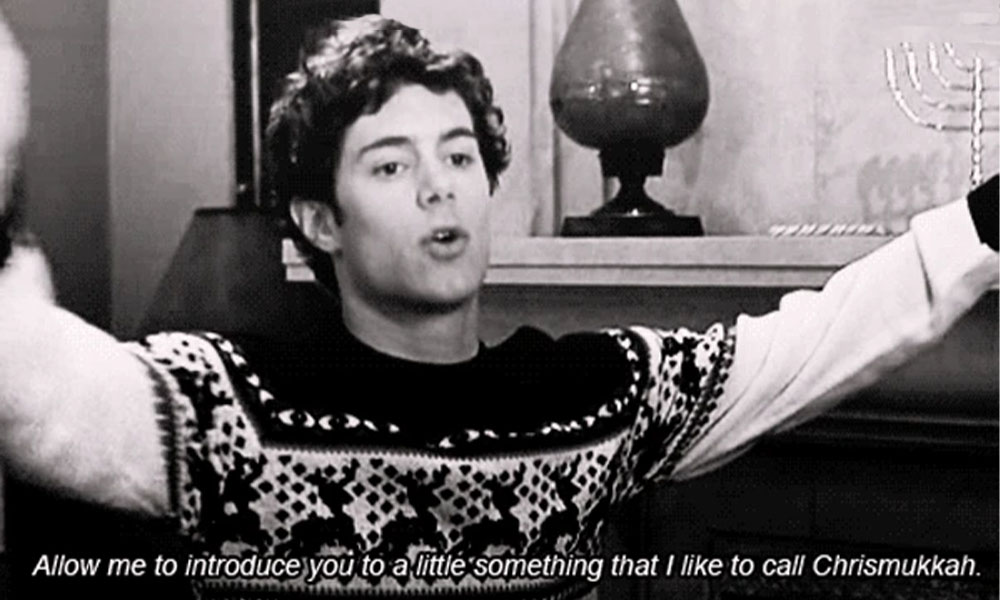

In the American context, Chrismukkah is a portmanteau popularized in 2003 by the hit teen drama series The O.C.; the character Seth Cohen (played by Adam Brody, more recently of Nobody Wants This fame) has a Christian mother and a Jewish father and so combines Hanukkah and Christmas festivities into one celebration (Fun fact: the show’s writers chose “Chrismukkah” over “Hanimas”).

Although Chrismukkah observers sometimes fuse elements of Christmas and Hanukkah more literally—resulting in quirky creations such as eggnog sufganiyot (jelly-filled donuts traditionally enjoyed during Hanukkah) or “Hanukkah bushes”—they’re more likely to celebrate separate traditions from the holidays, concurrently. “Most people did a little bit of Hanukkah and a little bit of Christmas, but they didn’t merge them,” explains Samira K. Mehta, author of Beyond Chrismukkah: The Christian-Jewish Interfaith Family in America, reflecting on her dissertation research about Christian-Jewish interfaith families—the main demographic celebrating Chrismukkah.

How is Chrismukkah celebrated?

In my household, it’s not uncommon to make latkes and watch a Christmas movie on the same day. To us, Chrismukkah epitomizes doing what we’d normally do to celebrate Hanukkah while embracing some Christmas customs.

Although some interfaith families more easily establish a consensus on the Christmas and Hanukkah traditions they observe, often family members negotiate to make Chrismukkah work. Mehta explains one example where a wife from the Church of Latter-day Saints agreed to forgo a Christmas tree, while her Jewish husband made room for a nativity scene on their mantel. For the wife, the nativity scene held deeper significance to her faith than the tree. While the husband’s acceptance of the less secular symbol might puzzle some, Mehta sees their agreement as a reflection of the thoughtful reconciliation often required to maintain respect in interfaith families during the holiday season. “She really thought about what she needed and didn’t just reflexively ask for what she wanted,” Mehta explains.

Chrismukkah commercialization

When I discovered Chrismukkah, I felt a sense of validation knowing there’s a widely used label for my family’s atypical blend of holiday customs. When I started using the phrase, I found that its play on words made the concept of joint Christmas-Hanukkah celebrations easier to explain. This relieved some of my stress from drawn-out explanations of being a Jew who celebrates Christmas, which often led to the dreaded question: “So, you’re, like, half Jewish?”

Nevertheless, I soon realized that Chrismukkah is also easy to conceptualize because it’s become hard to miss.

For example, in stores that typically stock “ugly Christmas sweaters” for the holiday season, you’re just as likely to find Hanukkah versions. Hanukkah-inspired spins on classic Christmas commodities include “Mensch on a Bench,” inspired by “Elf on a Shelf.” “I think it’s appropriate to call Hanukkah the Jewish Christmas in the United States,” says Joshua Plaut, Reform rabbi and author of A Kosher Christmas: ‘Tis the Season to be Jewish.

It’s clear that in American culture, Hanukkah and Christmas have become intertwined as a part of a broader holiday season promising festive cheer and big-time sales, but the evolution of Hanukkah into a “Christmacized” holiday didn’t start until after World War II, according to Tatjana Lichtenstein, a professor of Jewish studies at the University of Texas at Austin, in her article “How Hanukkah Has Changed in the U.S.” Seeking a way to emulate seasonal joy in their own communities, American Jewish leaders chose to prop up the story of Hanukkah. Plaut adds, “Hanukkah evolved, originally, as a commercial way to compete with Christmas. It was giving American Jews the ability to feel like Hanukkah was the time of year, which fell around Christmas time, where they could have their own separate holiday.” However, in an ironic twist, Hanukkah’s rise as a Jewish alternative to Christmas resulted in the two holidays becoming even more similar.

Can Christmas and Hanukkah actually be combined?

Chrismukkah seemed to make my family’s traditions—and those of others like us—more accepted and understandable. What I didn’t realize, though, was that Chrismukkah is only digestible because it oversimplifies Christmas and Hanukkah into one bite.

Most Jews reach an inevitable point in life when they realize that Hanukkah is not that religiously significant of a holiday. At its core, the Hanukkah story is one of Jewish nationalism and independence.

Hanukkah commemorates the story of the Maccabees, a family of Jewish rebels who led a successful revolution against the Syrian-Greek persecution of the Jews and occupation of Judea. After their victory, the Maccabees rededicated the Temple by lighting a menorah (a type of candelabra) with a small vessel of oil that miraculously burned for eight nights, earning Hanukkah the title “festival of lights.” While this is a historic moment in Jewish history, it holds little religious significance. In fact, it’s one of the few Jewish holidays with no connection to God or atonement, and no mention in the Hebrew Bible. So why was Hanukkah the holiday chosen as the Jewish parallel to Christmas, which celebrates the anniversary of a pivotal religious event in the Christian faith?

Jo David, rabbi of a multifaith ministry, explains that after the Temple was destroyed in 70 CE, the Jews weren’t again sovereign in their homeland until 1948, when Israel was declared a state. This made it dangerous for Jews to celebrate Hanukkah as a commemoration of overthrowing their previous rulers. Instead, they came up with a story focused on the miracle of the oil, says David.

In the same vein, Christmas wasn’t always the festive spectacle we know today. It wasn’t until the Victorian Era that the German custom of having a Christmas tree was expansively embraced in Anglophone societies. Before this, Christmas was celebrated somewhat discreetly, simply by going to church and having a meal with family. It was only after the publication of A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens that the holiday became a symbol of hope and joy, which churches built on, explains David.

Thus, despite the disparate importance of Christmas and Hanukkah to their respective faiths, they’re closely associated with each other not just because they occur during the same time of year, but because they’ve both been tokenized as their faith’s “miracle” holidays, as David calls them. This is how Chrismukkah is made possible—not by blending the deeper religious meanings of Christmas and Hanukkah but by creating a shared space for their simplified narratives of miracles and happiness.

The purpose of Chrismukkah

As a kid, I would constantly tell my friends how excited I was for the first night of Hanukkah. On occasion, I wore my kitschy Hanukkah apparel to school (my favorite was a pair of socks with dreidels on them). What I didn’t realize was that my efforts to showcase my Jewish identity through Hanukkah connected to my anxiety that celebrating Christmas made me a less faithful Jew. Initially, I thought the widespread use of the term “Chrismukkah” would dispel this anxiety, that people would start to understand that you can be Jewish but at the same time embrace Christmas celebrations out of respect for a family member. What I now know is that Chrismukkah doesn’t have much to do with Judaism or Christianity at all.

None of these traditions have much (or anything) to do with the birth of Jesus or the Jewish military victory against their ancient oppressors.

Chrismukkah is the by-product of the “miracle story” narratives, which allow us to forget the original messaging behind Christmas and Hanukkah and give rise to customs focused on festive bliss: Christmas trees, playing dreidel, setting up holiday lights, eating fried foods. I could go on! None of these traditions, however, have much (or anything) to do with the birth of Jesus or the Jewish military victory against their ancient oppressors. If they did, we wouldn’t place Hanukkah and Christmas in the same category, and Chrismukkah wouldn’t serve the purpose it does, which is to offer a space for members of interfaith families to feel included in the joy of the holiday season. This can only happen because Chrismukkah is not inherently religious.

While Chrismukkah was never meant to properly represent Judaism and Christianity, there will always be those who believe the idea is an insult to their faith. A press release issued by the Catholic League in 2004 even called Chrismukkah a “multicultural mess,” noting the insensitivity of “Yamaclaus” and similar inventions. I once felt this criticism overlooked the unique dynamics of interfaith families, but I’ve come to appreciate that perspectives on finding meaning in these holidays are diverse and deeply personal.

Rabbi David offers a more flexible perspective on engaging with the holiday season: “I think someone who’s living a rich religious life is someone who is in constant dialogue with themselves. How you determine what you want to do should be based on what feels right to you,” she says. This principle also guides her approach to balancing her beliefs as a rabbi with authoring novels—writing about Christmas traditions in her latest book, Midnight Miracle: A Regency Christmas Romantasy—under the pseudonym Nola Saint James.

To me, the (albeit commercialized) magic of Chrismukkah is that, when it’s not taken as a serious reflection of Hanukkah or Christmas ideals, it can alleviate the imposter syndrome that’s often felt by Jews and Christians observing cultural traditions of a faith outside their own. That being said, each December I’ll continue to sing the dreidel song, indulge in my annual screening of Frosty the Snowman, and maybe even give someone I love a yamaclaus.

6 thoughts on “Chrismukkah: As Defined by a Jew Who Celebrates”

I am a Jew who has not celebrated Chanukah for a number of years for two reasons.

The holiday celebrates a fable created by ancient rabbis to deal with the fact that God did not ordain it has God has for all of our other holidays in the Torah. I am a secular Jew and celebrate those in the Torah as cultural practices

Secondly, it celebrates less a defeat of Syrian-Greeks than the evilness of the Maccabee’s civil war with other Jews and becoming a tyrannic family for a fortunately short period.

I believe Chanukah has become so common in America to have something to give Jewish children even better than Christmas. Gift for each of the 8 days.

As my Jewish German mother who gave only one gift, a dredel ad nuts to play with. The American practice is narrish -foolish.

Wonderful article and astute comment, but an important element is missing: Rashi called Chanukah a “woman’s holiday” – “because they were involved in the miracle.” How? The midrash about Mattathias’ daughter Hannah lodging a nonviolent protest against the law of the first night explains that. Which is why

Joel Mandelbaum called my 1980 opera on the subject (produced at HUC-JIR during Chanukah in 2014)

“the quintessential Jewish opera.” See https://leonardjlehrman.com/Hannah.html

So, now I get to give an additional ‘gift ‘ to my grandson . Also, has 2 older cousins of the same faith.

A psychiatrist colleague and I are having a “contest” for the best brief essay by a psychiatrist on how Chrismukkah can inspire peace endeavors.

Maybe the easiest way to alleviate imposter syndrome is to not celebrate a holiday outside your tradition. That doesn’t mean you can’t honor those who do (and celebrate *with* them) but you don’t need to create or perpetuate a made-up holiday to assuage your guilt.

I don’t understand how any self-respecting (or Judaism respecting) rabbi can say that Chanukah is the Jewish Christmas. The two holidays have nothing in common aside from the time of the year.

Any attempt to meld the two is an insult to and distortion of both. One is about the birth of the savior (a far cry from today’s commercialism) and the other is the reassertion of Jewish power and practice. If there hadn’t been a Chanukah, there would not have been a Christmas.