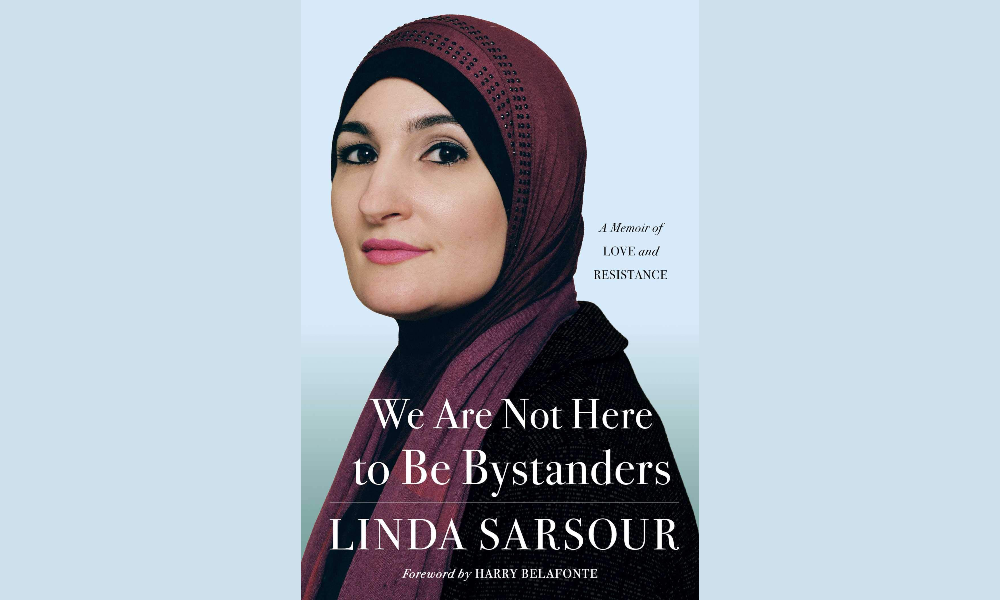

Book Review | ‘We Are Not Here to Be Bystanders’

We Are Not Here To Be Bystanders: A Memoir of Love and Resistance

By Linda Sarsour

Simon & Schuster

272 pp.; $26.00

In his foreword to Linda Sarsour’s memoir of political activism, Harry Belafonte remarks, “It wasn’t that long ago that we lost Martin and Malcom and Bobby.” He is comparing the vilification of Sarsour, the hijab-wearing, Brooklyn-born Palestinian-American, for her anti-Israeli politics to the murderous racist violence of the 1960s. It seems a stretch. While Mr. Belafonte (as Sarsour always respectfully refers to him) is writing from the vantage point of age 93 and entitled to his own perception of time, the past half-century has witnessed enough change in the condition of American minorities as to make the killings of Dr. King, Malcom X and Robert Kennedy seem signal events of a fairly distant time.

When Martin Luther King was killed in 1968, there were six African-American members of Congress; today there are more than 50. According to the Pew Research Center, before the 1965 Immigration Act, a law deeply influenced by the civil rights movement, 84 percent of U.S. immigrants were from Europe or Canada; nowadays those countries account for just 13 percent of an immigrant population whose share of the overall population is near the record levels of a century ago.

These contrasts do not make for a color-blind America (a civilian review board to review charges of police brutality, typically against African Americans, was a controversy of New York City politics in the 1960s just as it has been in the 21st century) but they did set me time-traveling.

Sarsour’s book could in many respects be the same political coming-of-age story that first-generation Americans have been telling in Brooklyn for decades: life in an ethnic neighborhood (in her case the Palestinian enclave of Sunset Park); the bilingual, bi-cultural household; the parental mistrust of American mores versus the desire to fit in; the pull of tradition (her own evidently happy, arranged marriage is to a man she barely knew); the closeness of her big nuclear family and still bigger extended one; the encounter with intolerance; the attraction of political activism. Jews, Greeks, Italians, Puerto Ricans up from the island, African Americans up from the South and many others have all told similar stories.

In fact, some of Sarsour’s causes echo those of Jewish activists decades ago. Getting the public schools to recognize two Muslim holidays and campaigning against police infiltration of mosques and Muslim neighborhoods are of a piece with my grandfather arguing with the cops to keep his tailor shop open on Sunday, as well as activists defending Jews who were unfairly surveilled and tarred as disloyal for their left-wing politics in the days of the Rosenbergs. Sarsour’s claim to public attention was as an organizer of the Women’s March held the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration. In her fear and loathing of Trump, she found common cause with a great many Jewish voters, especially women.

None of this accounts for the vilification Sarsour has received. That is primarily about her support of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement that targets Israel; her alleged insensitivity to Jewish planners of the Women’s March and her apparent admiration for Louis Farrakhan. On these issues, in her memoir, Sarsour ranges from defensive to silent.

The BDS movement is a neuralgic issue for Israelis and Israel’s supporters, as it seeks to delegitimize the Jewish state in ways that no one seeks to delegitimize, say, China for throwing a million Muslim Uighurs into concentration camps. Sarsour’s family came from the West Bank, and she has cousins in Israeli jails. While I recognize Israeli alarm over BDS and would personally oppose it, it strikes me (time-traveling again) as the sort of old-country politics that immigrants have been packing in their baggage for ages along with the old country’s outfits, recipes, religions and folklore. Some of our Jewish forebears packed a stack of Bolshevism that made more sense in the prison that was Tsarist Russia than on Orchard Street. Palestinians can rightly argue that they have been delegitimized for all means of nationalist expression and, while the Israeli definition of terrorism can be expansive, the BDS campaign strikes me as a mode of protest preferable to bombing Israeli buses, markets and wedding halls and one that Jews should be able to rebut, or else make some meaningful concessions on the West Bank.

On the other hand, it is odd to read the memoir of an Arab American activist (Sarsour was Director of the Arab American Association of New York) that describes the time period of the mother of all nakhbas, the death and displacement of millions of Syrians, many for demanding less of their government than aggrieved Arabs in Brooklyn have demanded of the NYPD, with barely a nod to that colossal intramural Arab injustice. Equally absent is any pre- 9/11 history of attacks by various Islamist terrorist groups on the World Trade Center, on two U.S. embassies in East Africa and on the USS Cole that empowered Islamophobes here and primed an audience for their arguments.

As for the Women’s March controversy, Sarsour details her version of a breakup of the leadership team that her fellow organizer of the 2017 Women’s March, Vanessa Wruble (who is Jewish) attributed to her concerns about anti-Semitism. Sarsour’s defense against that charge seems to be twofold: First, she says that middle-class women have difficulty deferring to black women who, suffering the worst from American racism, must be granted the lead; and second, that many of her best political friends are Jewish. A couple of times, she cites Senator Bernie Sanders’s approval of her work. Interestingly, she supported Sanders in 2016 rather than follow the lead of black women who (outside of political activists of Sarsour’s own generation) preferred Hillary Clinton.

The allegation of Sarsour’s anti-Semitism that is hardest to refute is her recognition of Farrakhan as a respected elder voice. She has attended his annual Founder’s Day event, at which Farrakhan has, not surprisingly, reiterated his specious claim that Jews were central to the Atlantic slave trade, a claim that historical research does not support and that reeks of conspiratorial anti-Semitism, accusing Jews of nefariously and covertly being in charge. On this charge, she is silent.

Sarsour reminds me of the New Left activists who throve 50 years ago, gifted at organizing a crowd and expressing its grievances. In fairness, her achievement of getting the New York City public school system to grant days off for Muslim holidays was a greater gain for more people than many New Left groups ever achieved. One unattractive quality they share, though, is a self-righteousness buttressed by faddish political theory. The New Left could imbibe Herbert Marcuse’s writings on false consciousness and dismiss the American people’s clear lack of interest in revolution with the confident assertion that the American people don’t understand their own lives. Sarsour, in despair over Trump’s election, remarks with sadness that “a disappointingly high number of white women, 49 percent, voted against their own interests” by supporting Republican candidates. Was a rural evangelical Christian woman who opposes abortion on religious grounds, enjoys target shooting and whose husband lost a factory job when his employer moved the plant to Mexico voting against her own interest when she voted for Trump? Politics entails real conflicting interests, not just my real interests versus your delusions.

The Women’s March did energize opposition to Trump, and women voters and candidates were central to the Democratic gains of 2018. They were typically middle-class suburbanites, quite a few with experience and expertise in U.S. defense and security. If the Democratic Party holds on to those gains and expands upon them, it will likely be in the name of a more centrist politics than those of Bernie Sanders, the BDS movement or Louis Farrakhan. That would not be the first time that national politics proved a lot less revolutionary than the convictions born and sharpened in the half-assimilated ethnic enclaves of Brooklyn and Queens.

Robert Siegel is a special literary contributor to Moment. He was the host of NPR’s All Things Considered.

3 thoughts on “Book Review | ‘We Are Not Here to Be Bystanders’”

Omissions are more telling than actual mentions of controversial subjects. Also, BDS is an atrocity and those who are for it forfeit their right to speak on the same ground as those who have a history of genocide, ethnic slavery and persecution against their humanity. Prejudice is moral and political poison…those things that are explicitly said, labeling anyone as less than valuable in the sight of God, or punishing them for their success in overcoming adversity. The likes of Louis Farrakhan should be avoided at all cost. The same applies to those who commend them. Respect must be earned and then only when it is proven by words and actions. Beware of those who hold as worthy the very ones who are least.

Lewis Farrakhan has been implicated in the murder of one of our greatest civil rights leaders, Malcolm X. Farrakhan also publicly intimidated a witness to the brutal murders of members of the Hanafi Muslim sect into not testifying. The 1973 murders were committed in the building purchased for the sect by one if its members, Kareem Abdul -Jabbar.

How anyone who purports to be a progressive concerned about the rights of African Americans could support Farrakhan is beyond belief.

I have enjoyed reading Linda’s memoir. It resonates to many marginalized communities across different ages. I admire her boldness and determination. We have to let our voices be heard for the good course.