Book Review: The Rise of Abraham Cahan

From Socialist to Zionist

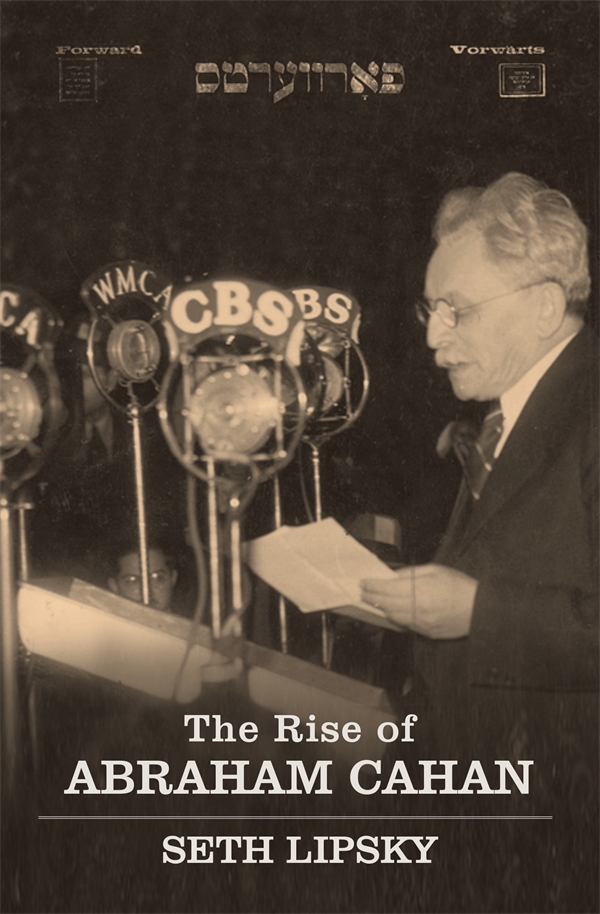

The Rise of Abraham Cahan

Seth Lipsky

Schocken

2013, $18.63, pp. 240

All readers interested in the fate of Eastern European Jewish life in 20th-century America owe a significant debt to Seth Lipsky for his intelligent and nuanced portrait of Abraham Cahan (1860-1951). The reason is not simply that his great career is inherently fascinating as well as hugely influential: Cahan’s founding of Forverts (the Yiddish Forward) in 1897; his encounters with socialism, Zionism, communism, The American Federation of Labor and the Jewish socialist Bund; his meetings with historic figures from Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Vladimir Jabotinsky, David Ben-Gurion and Alfred Dreyfus to Lincoln Steffens and the Belzer Rebbe—the so-called “miracle worker” and “most renowned Hassidic figure of his time”; his literary life as the author of the landmark novel, The Rise of David Levinsky, and his famous falling out with the novelist Sholem Asch over Asch’s alleged apostasy in his novel, The Nazarene, that Cahan refused to publish and denounced in the Forverts. All this alone would make good reading.

Lipsky, however, frames the narrative in a different way. He incorporates Cahan’s journalistic, political and literary lives into a powerful account of his metamorphosis from socialist radical in Eastern Europe to Zionist proponent in the late 1920s. This metamorphosis is fascinating for many reasons, but principally because it shows how Cahan, along with many others, brought into American life one of the most powerful and defining characteristics of the Eastern European Jewish world from which he came.

Born in Lithuania into a Yiddish-speaking family, Cahan came to America in 1882 at the age of 22, and rose to become one of the legendary American newspapermen, an electrifying speaker and public organizer whose influence far exceeded the 250,000 American readers the Forverts had at its height. Cahan gave what he imagined to be “the first socialist speech in Yiddish to be delivered in America,” and by the end of his life he commanded the attention of presidents.

In its starkest form, Cahan’s transformation re-enacted the battle between the Jewish universalism and equally strong Jewish nationalism that raged throughout the Yiddish-speaking world from the 18th to the 20th centuries. The universalist aspirations of the haskalah movement, begun as the “Jewish Enlightenment” in Germany in the 18th century, urged integration of Jews into Gentile society and emphasized a moral universalism that could be traced back to the prophetic tradition. But almost from the beginning, this was met in Eastern Europe by an equally powerful anti-assimilationist, nationalist fervor. The haskalah in Germany sought to eliminate Yiddish, while in Eastern Europe Yiddish was undergoing a widespread and deep cultural flowering. Universalist ideas in combination with a perceived political and social helplessness helped spur the rapid growth of socialist thinking among the disaffected Jewish youth of Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine and Russia. Thinkers and writers went out “into the people” to preach their radical, socialist beliefs. Sholem Aleichem captured the tragedy of Tevye’s daughter, Hodel, who follows her husband into exile on behalf of these ideas. Others laid the theoretical groundwork for what was called “the Jewish national idea,” whose larger ramifications gave birth both to Zionism and its hybrid twin, so-called Jewish autonomism.

Reclaiming the land, reclaiming the identity of the Jewish nation, reclaiming and inventing a specifically Jewish destiny in the modern world through Zionist nationalism was, in Cahan’s words, “the fire [that] has melted all the class and ideological conflicts.” Both Zionism and anti-Zionism sprang from an acute perception of the historical circumstances Jews found themselves in at the advent of the modern period. Cahan asked, “In such a situation, what meaning can there be to declarations on principles, or class struggle, or social revolution?” Zionism became for Cahan, in Lipsky’s words, “a defining issue of Jewish identity in the twentieth century.”

Yet, as Lipsky makes abundantly clear, before his 1925 trip to Palestine, Cahan was anything but a Zionist sympathizer. He had denounced and ridiculed Jabotinsky’s notion of the “Iron Wall” between Arabs and Jews in Palestine just two years earlier. His attitudes paralleled those of the Reform Movement generally, which “not until the rise of Nazism in Germany in the 1930s depart[ed] from its long hostility to the idea of a Jewish nationality and officially [came] out in favor of Zionism.” These attitudes grew from Cahan’s labor organizing, his avowal of socialist principles, his hatred of capitalism and his deepest understanding of social justice.

Lipsky tells the compelling story of Cahan’s metamorphosis as a byproduct of his American experience. “We regarded ourselves as human beings, not as Jews,” Cahan wrote about his early attitudes. “There was only one remedy to the world’s ills, and that was socialism.” Very early on, however, through his association with the American Federation of Labor, Cahan began to see that this “non-socialist, even anti-socialist” organization might realize the goals of socialism. And in years to come, America’s “careful balance between the rights of the individual or of states against a national identity allowed [Cahan] to understand his Jewishness not as a contradiction of universal values but as an essential precondition of it.” In effect, Cahan enabled the shaping of a distinctly American Jewish sensibility.

The figure of Cahan with his towering accomplishments makes this reader wish for a more expansive treatment. Lipsky quotes a haunting passage from The Rise of David Levinsky: “And yet when I take a look at my inner identity it impresses me as being precisely the same as it was thirty or forty years ago. My present station, power, the amount of worldly happiness at my command…seem to be devoid of significance.” Only a much longer work could have penetrated the mystery of that inner identity and through it the perplexing and still dynamic inner identity of the Eastern European Jewish world in America that gave us Abraham Cahan.

Jonathan Brent is executive director of The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. He is the author of Stalin’s Last Crime and visiting professor of East European and Soviet literature and history at Bard College.