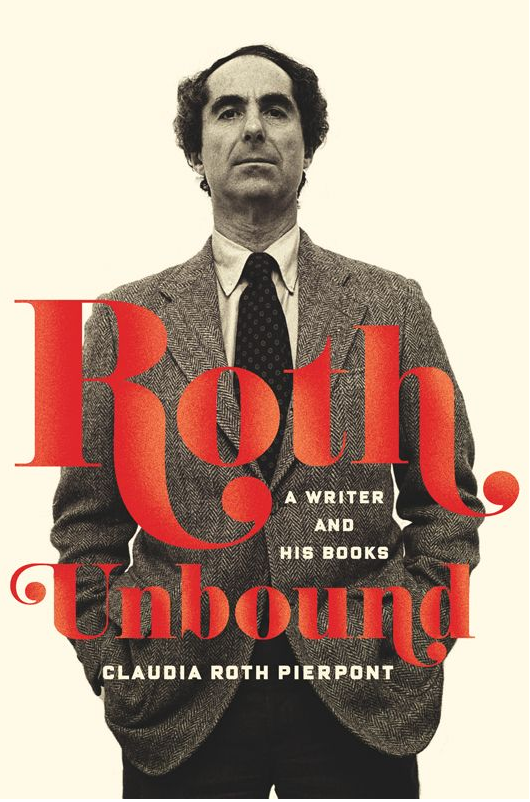

Book Review // Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books

Life Beyond Portnoy

By Alan Stone

Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books

Claudia Roth Pierpont

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

2013, pp. 353, $27.00

Philip Roth’s pen has finally run dry, and he has announced his retirement. As if to commemorate that event, Claudia Roth Pierpont—no relation, but a good friend and a superb writer—has produced this brilliant literary biography, Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Books. Her project, which began as an essay for The New Yorker, where she’s a staff writer, grew into this extraordinary, encompassing account as the dialogue between the two writers deepened into friendship and mutual admiration. Roth, as anyone who has met him can tell you, is an amazingly charming man. One can sense this on every page of Roth Unbound. That said, Pierpont’s literary judgments are exacting: One comes away from her book with the conviction that Roth is the most important American writer of his generation.

Pierpont’s biographical task might seem particularly problematic to Roth’s diligent readers. It seemed he was always writing about himself, his American Jewish identity, his family in Newark, his angst, his mortality and his adventures in the “skin trade.” In the trajectory from Goodbye, Columbus to Portnoy’s Complaint to The Counterlife to American Pastoral to The Human Stain to the four short farewell novels ending in Nemesis, he seemed to be telling stories drawn from his own life. Scholars have put him in the category of confessional novelists. But Roth was also hiding his true self, and his elaborate variations on the authorial voice of the narrator became his post-modern literary signature. Pierpont suggests he was at first driven to this by the reactions to his early writings. Roth had not expected the rage he elicited from conservative Jews when he published his early short stories. As Pierpont describes it, he was nearly lynched during a 1962 forum at Yeshiva University (YU). He may have been confessing, but he was also, they believed, revealing shameful truths about the Jews. “Would you write such stories if you lived in Nazi Germany?” asked the moderator. The verdict at YU was clear: He was a self-hating Jew and an anti-Semite.

Roth’s lasting and inescapable reputation among many readers was solidified in 1969 when he published Portnoy’s Complaint, the story of a compulsive masturbator confessing on his psychoanalyst’s couch. For Roth, fame, celebrity and notoriety arrived all at once. As Roth tells Pierpont, it was “a novel in the guise of a confession” read “as a confession in the guise of a novel.” Those who read it as a confessional committed two kinds of offenses against Roth. On the one hand, they failed to recognize how much radical literary invention and originality was necessary to write it. Stylistically, Portnoy was a break with Roth’s literary forebears and mentors. On the other hand, readers assumed they knew the author intimately. As Pierpont reports, Jacqueline Susann, author of Valley of the Dolls, commented on The Tonight Show that she’d like to meet Roth but would not shake his hand. Men accosted him on the streets of New York, saying, “Leave it alone, Portnoy.” Roth escaped from New York, but it would take him almost a decade to escape the voice of Portnoy that sounded in the less successful novels that followed.

Pierpont believes he got his creative potency back a decade later in 1976 with The Ghost Writer, his version of the Anne Frank story. He had found Heine’s Maskenfreiheit, the freedom conferred by masks. Nathan Zuckerman became Philip Roth’s alter ego, his story teller and liberating mask. The Ghost Writer, in Pierpont’s perfectly pitched judgment, “is one of our literature’s rare, inevitably brief, inscrutably musical, and nearly perfect books.”

Pierpont gently unmasks Philip Roth, telling us what was actually happening in the life he was living alongside the books he was writing and how he was expanding his intellectual and moral horizons. He taught literature in universities and traveled to communist Czechoslovakia, where he befriended writers Ivan Klima, Milan Kundera and Vaclav Havel, and spent time in Israel. His circle of friends in the literary world, in the arts and in music kept expanding.

Roth would go on from Ghost Writer to a series of great, deep and even profound novels, many of them using Zuckerman as character and narrator. The most critically acclaimed of these is American Pastoral. In it, Zuckerman, now impotent and incontinent after prostate surgery, tells the story of his boyhood idol, Swede Levov—born Seymour Irving Levov—a handsome, blond-haired ballplayer who was an American in “the regular American guy way.” The Swede marries Miss New Jersey, an Irish Catholic girl, and takes over his father’s glove factory in Newark. But Zuckerman’s “Jewish Apollo becomes a latter day Job.” His assimilated American life is ruined when his daughter, Merry, turns to domestic terrorism and sets off a bomb in protest of the Vietnam War that kills a beloved doctor. As Zuckerman tries to understand the Swede, we are launched into the great postmodern novel about the 1960s when America ran amok: the revulsion against Vietnam, the urban riots, a war in the city of Newark and the question of how a generation of children came to hate their parents. “Among the most affecting scenes in the book,” Pierpont writes, “are the face-offs between father and daughter,” with Roth understanding them both and all the other conflicting voices of the 1960s as well. That understanding made critics wonder about Roth’s politics. His response was, “I don’t write about my convictions, I write about the comic and tragic consequences of holding convictions.” American Pastoral won the Pulitzer Prize in 1998. Roth had become more than a Jewish American confessional writer—he was a towering presence in American literature.

“Roth has grown in stature as he has grown older. At his best he is now a novelist of substantially tragic scope, at his very best he reaches Shakespearian heights.” It is hard to imagine greater praise for a writer. It comes not from Pierpont but from the Nobel Prize-winning novelist and typically grudging critic J.M. Coetzee in his New York Review of Books review of Roth’s counterhistorical 2004 novel, The Plot Against America.

One expects that Pierpont, as a friend, will be gentle in describing Roth’s many adventures as a womanizer and how Roth became the target of feminists, many of whom thought all of his female characters were presented as sex objects. Pierpont manages to navigate these troubled waters with admirable skill and candor, letting critics speak for themselves and conceding that Roth may be a novelist for men. In one of her last chapters, she considers The Humbling, one of the novellas leading up to Nemesis. In it, an aging actor, Simon Axler, who has had chronic back pain and a nervous breakdown (maladies that have afflicted Roth) falls in love with a 40-year-old woman who has lived her adult life as a lesbian. As Pierpont describes it, “the book builds toward a series of in your face sex scenes,” but she admits that they lack Roth’s usual comic genius or his ability to convey that sex becomes “the great tingling counterforce to death.” She obviously does not abdicate her literary judgment. Then, with her diplomatic hat on, she explains that Roth did have a torrid affair in these years with a 40-year-old former lesbian, but that it ended on friendly terms. Pierpont also permits herself the observations that “the affairs were becoming shorter and more difficult to maintain—just like the books.” She goes on: “If this book were a conventional biography, there would be names and dates; that will come along, in time.”

But she does tell us that Roth briefly dated Jacqueline Kennedy: “Would you like to come up? Of course you would,” (emphasis added). Roth opined, “kissing her was like kissing a billboard.” One wonders what Jackie thought about their two dates. What was it like kissing Philip Roth? We will never know.

A recurring theme implicit in all of Roth’s novels is central to Nemesis, his farewell novella. Roth, who spent five years in analysis and late in life was hospitalized twice for depression, rejects the Freudian (and religious) view that we are somehow complicit in our own suffering, that we have reasons to feel guilt, shame and responsibility. This is explicit in Nemesis. Roth’s last hero is the ultimate decent young man incapable of irony, cynical humor or hiding behind social masks. He is devoted to the health of the young boys in his Newark gym class. It is the polio epidemic of 1944 in Newark, and one by one his students succumb. He retreats from the city to a summer camp where soon several of the campers come down with polio. Finally, it becomes clear that our hero, unknown to him, is the person who has been spreading the polio virus. Pierpont sees in this Roth’s vision of the fate for which the hero ought feel no guilt, no shame and no responsibility. And yet Roth’s hero spends the rest of his life feeling responsible and punishing himself. J.M. Coetzee found in this novel the imprint of Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex, who unwittingly brought the plague on Thebes. His essay review is entitled the “Brink of Morality,” and that seems an enlightened way to think about Roth’s novels—they are actually meditations on the human condition and its moral possibilities.

In 2011, President Barack Obama presented Philip Roth with the National Humanities Medal. Many of his readers now believe that the Nobel Prize should follow. Pierpont has made the case.

Alan Stone is the Touroff-Glueck Professor of Law and Psychiatry in the Faculty of Law and the Faculty of Medicine at Harvard University.