Book Review | Princess Schweppessodawasser’s Surprising Romance

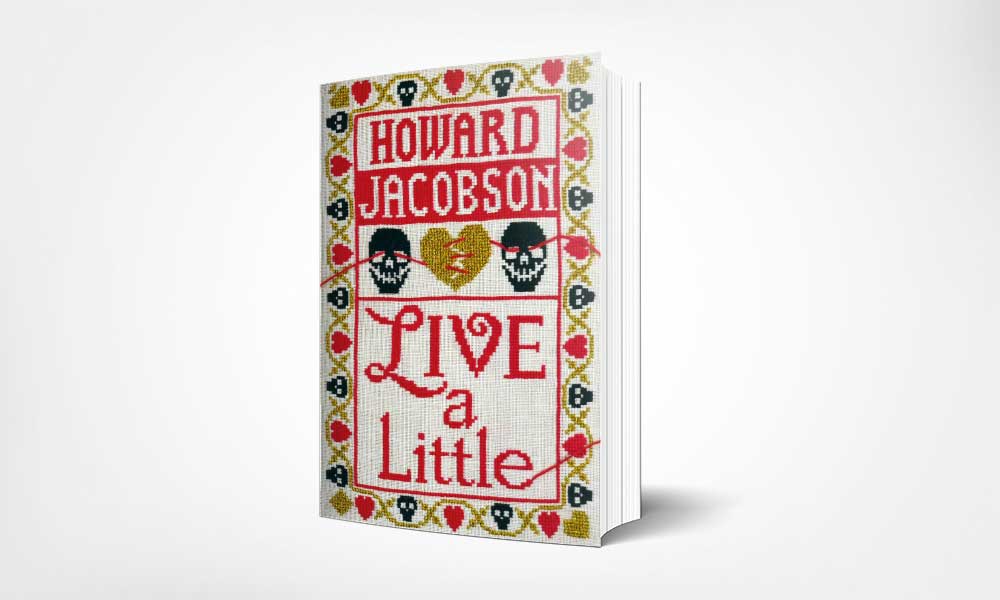

Live A Little

By Howard Jacobson

Hogarth Press

2019, 304 pp, $27

Language is failing Beryl Dusinbery. She is 99 years old and having trouble retrieving words. “One minute she has a word, then she hasn’t. Where does it go?” Conversely, Shimi Carmelli, 91, can’t forget. “Selective morbid hyperthymesia,” he calls it. One burdensome memory in particular refuses to recede.

Live a Little, Howard Jacobson’s 16th novel, is ostensibly a love story about these two nonagenarians, who live across from one another on North London’s Finchley Road. But its themes have less to do with romance than with humiliation and regret, privilege and bad parenting, a temperamental prostate and, above all, words. Those themes have run through Jacobson’s novels (and his columns for the British newspaper The Independent) from retellings of Genesis and the Shylock story to the contemporary The Finkler Question. This new book is classic Jacobson: smart and quippy, full of literary allusions and mined with barbs.

The cover art features skeins of hearts and skulls, and the latter ought to serve as a trigger warning. Beryl is no sweet old lady; she’s self-absorbed, nasty, racist and verbally abusive to the two long-suffering caregivers who dutifully tolerate her offensive behavior. She refers to one as a “Russian whore” and hypothesizes that the other has bad posture because she’s from Africa and “It’s what comes of eating lizards and carrying baskets of bananas on their heads.” Sometimes Beryl falls down just to give them something to do. “I see it as a favor,” she says. “It increases their job satisfaction.”

She’s not any nicer to her sons. Actually, she’s not entirely sure how many children she has—possibly three? They have little good to say about her, and the feeling is mutual. She named one Pentheus, after the Greek mythological figure who was eaten alive by his mother. Another son is called Sandy, short for Tisander, who was murdered by Medea, one of her favorite literary characters. A former schoolteacher who once distracted men with “the cruel, angular cubism of her face,” Beryl now prefers to be known as The Princess Schweppessodawasser, a nom d’oubli for the heroine of One Thousand and One Nights—or something like that anyway, as the actual name of the character eludes her.

The imperious Beryl seems an unlikely match for the aloof Shimi Carmelli, a self-styled cartomancer who tells fortunes at Fing Ho Chinese Banquet Restaurant, just beneath his apartment. He is a “frightened, burdened man” with a long, miserable face, “like a horse waiting to be shot.” He is nevertheless pursued with enthusiasm by a group of elderly women referred to as the Widows of North London.With his “slightly crazed, insurrectionary stare” and his fondness for Cossack hats, he reminds many of the Widows “of the fathers and grandfathers they left behind in their old countries or know only from faded photographs.” Also, he can do his own buttons and speak without spitting, which makes him a catch.

Shimi is not especially interested in any of them, however. He’s preoccupied by his bladder—before leaving the house he makes a mental map of all of the public urinals along his route. An enlarged prostate is only part of the problem. Shimi is haunted by the moment when, at age 11, he tried on his mother’s underwear. He’s been full of guilt and shame and sexual confusion ever since: “He climbed into his mother’s bloomers and tumbled into hell.” He even feels responsible for his mother’s death: “Could he have thought her into dying?” After the two characters meet at a funeral, Beryl helps unburden Shimi in a series of conversations that take place at Regent’s Park.

“Spill!” Beryl commands.

“No,” he says. “You have the floor.”

“I relinquish it. Go on. What’s amused you?”

It astonishes him how easily, after 80 years of incarceration, the confession slips out of his mouth. “You asked me where I was. In my mother’s bloomers.”

She barely blinks.

That Beryl might transform sufficiently to become empathetic—to anyone—seems farfetched given her general lack of humanity. Perhaps one could attribute this to the power of love. But this incongruence in her personality is beside the point, because this novel, and these passages in particular, seem almost theatrical, a vessel to channel Jacobsian thoughts. “Jew-boys are made of words,” Beryl tells Shimi, whose mother was “a Hebrew” and whose father’s people were “Maltese pretending to be Italian.”

“‘I’m only half a Jew-boy,’ he protests.”

This exchange seems at first a jarring comment in a book that is not explicitly Jewish until it sort of is. And it serves as a reminder that even when the contemporary British Jewish experience isn’t at the heart of Jacobson’s material, it’s still in the fabric. When The Finkler Question won the Man Booker Prize in 2010, Jacobson told The New York Times he’d rather be called “the Jewish Jane Austen” than “the English Philip Roth.” It’s an aspiration he arguably achieves here in what might be called a comedy of manners, albeit in a much darker shade than would have suited Jane.

The character of Shimi made me recall my own conversation with Jacobson some 25 years ago, when I profiled him in London for the launch of his book and documentary Roots Schmoots. He spoke about the Jewish mind and the love of language: “You have to get the thing right. You have to say it right, you have to mean it right, and you have to worry it right.” He talked about the “fretting and worrying at something that could exhaust the gentile mind, but which Jews can do with one another ad infinitum.” This latter observation pretty much sums up Shimi and his mortification.

Actually, Beryl is all about words, too—words that evade her and words she would do better not to speak. “Life isn’t just words,” her son pleads, critiquing her icy approach to motherhood. “Yes it is,” Beryl fires back. “Life is only words.”

Even if the Beryl-meets-Shimi romance is unconvincing, this novel is worth reading—for the words.

Susan Coll is the author of five novels, most recently The Stager.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.