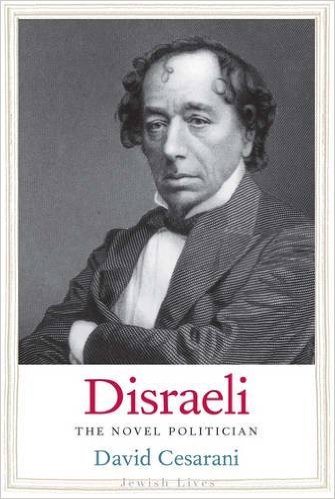

Disraeli:

The Novel Politician

David Cesarani

Yale University Press

2016, pp. 304, $25.00

How Jewish Was He?

by Norman Gelb

David Cesarani’s succinct new biography of preeminent Victorian statesman and novelist Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), Disraeli: The Novel Politician, challenges the commonly held view of Disraeli as having played a heroic role in Jewish history. Instead, Cesarani portrays Disraeli as a political opportunist “infused with a contempt for traditional Judaism,” whose literary writings “sketched the first draft of the Jewish world conspiracy theory” and made a “fundamental contribution to modern literary anti-Semitism.” Disraeli, who has erroneously been called Britain’s first Jewish prime minister, was baptized by his father into the Anglican Church when he was 12 years old. However, he never actually denied his Jewish heritage. Instead, he skillfully manufactured a myth of aristocratic Jewish origins that he would pragmatically exploit when convenient and completely ignore when not.

Disraeli: The Novel Politician is the late English historian’s final book. David Cesarani, who died of cancer last October at age 58, was considered the foremost British historian of the modern Jewish experience of his generation.

Countless historians before him have documented Disraeli’s rise to power and his importance as a politician. Disraeli entered the House of Commons in 1837, and in the 1850s and 1860s served first as Chancellor of the Exchequer and then as Leader of the House of Commons. After a brief first term as prime minister in 1868, Disraeli regained office in 1874. A major player on the international stage, Disraeli was enormously popular at home for expanding and consolidating Britain’s position as a worldwide imperial power. He was credited with reuniting the divided Conservative Party and was instrumental in its development as a modern political force. He was the driving force behind legislation that improved social conditions for the most vulnerable populations in Britain, including new laws to regulate public health and others designed to prevent the exploitation of workers and improve the general public’s access to education. He was close personal friends with Queen Victoria, who made him the Earl of Beaconsfield and reportedly wept when he died.

Cesarani’s biography follows a newer trend of historians viewing Disraeli through a more critical lens. Until comparatively recently, with the exception of a few anti-Semites, scholars have fairly uniformly viewed Disraeli as an admirable and effective, if exotic, British statesman. But lately, the perception of him as a worthy public benefactor has come under fire.

British historian Robert Blake, who wrote a very comprehensive biography of Disraeli, conceded that the man’s political career was an impressive one but added that “there is no need to make it seem more extraordinary than it really was,” since other political figures deserved much of the credit for achievements attributed to Disraeli. Another recent biography of Disraeli, by Douglas Hurd and Edward Young, described his contribution to British politics as “vast, transformative and special” but also portrayed Disraeli as a manipulative man for whom politics was “always a game in which pieces were moved about to…outflank the enemy. It had no moral content.” And British historian John Vincent has called Disraeli “a politician of very few principles or beliefs… He spent much of his life scheming.”

Cesarani, unlike previous biographers of Disraeli, spends relatively little time on his subject’s dynamic and often controversial political life. Instead, he devotes his attention to another key aspect of Disraeli’s persona: his vaunting of his supposedly aristocratic Jewish origins and the special distinction he claimed they conferred on him. But despite Disraeli at times making a calculated use of his Jewish background, Cesarani shows that in actuality Disraeli’s relationship to Judaism and to issues facing Britain’s Jews was a deeply troubled one.

Disraeli was the grandson of Jewish immigrants to Britain from Italy and was born in London to Jewish parents. Even though he converted to Christianity, attended church on a weekly basis and was an avowed champion of the Anglican Church, Disraeli faced anti-Semitism throughout his adult life, including claims that his prime motivation in politics was to “pursue an alien agenda” and advance “Hebrew” causes.

Disraeli’s conversion permitted him, upon election, to evade bans on non-Christians becoming members of Parliament. Disraeli knew when and how to invoke his Jewish origins. At times, he proudly boasted of his exalted “racial” Jewish birthright. When scornfully called a Jew by a fellow parliamentarian, he cuttingly replied that when his accuser’s ancestors “were savages on an unknown Island, mine were priests in the Temple of Solomon.” And Cesarani notes that in his fictional writing, Disraeli sometimes played up “the glories of the Jewish race.”

Cesarani dismisses Disraeli’s public exaltations of his Jewish origins as a mere affectation, stating that as a politician “he was insensitive or insensible to a range of Jewish issues” and was, at best, inconsistent with regard to Jewish matters. In December of 1837, soon after his first election, Disraeli uncharacteristically kept his head down while other MPs heatedly debated whether Sir Moses Montefiore or any other Jew should be allowed to hold political office. And unlike many other British leaders, he remained completely silent during “the Damascus Affair,” a blood libel charge against a dozen prominent Syrian Jews that resulted in widespread riots against the Jewish community in Damascus and triggered protests around the Jewish world.

Even as prime minister, says Cesarani, Disraeli chose to completely ignore “vicious [verbal] attacks on the Jews” by establishment figures and, in his many travels to Europe and the Middle East, made no effort to seek out Jewish sites or groups. He generally seemed to have little knowledge of, or interest in, Jewish history. Cesarani notes that Disraeli, in one of his early writings, said Britain enjoyed great freedom under the Plantagenet monarchs, but made no mention of the fact that under Plantagenet rule, Jews “suffered exploitation and massacre.”

Cesarani offers nuanced revisions and correctives to prior scholarship on the nature of Disraeli’s Jewishness. For instance, in The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt suggests that Disraeli’s “Jewish obsession was a strategy to combat his own sense of social inferiority…as an outsider in upper class Tory circles….” [He invented] “the myth of Jewish racial superiority” to match the perceived nobility of members of the British aristocracy.” Cesarani contends that “the chronology of this explanation does not work” because, he notes, Disraeli was able to “[rub] shoulders with both raffish and respectable aristocrats” early on, “even if he was not yet invited to their country houses.”

Few other historians fully concur with Cesarani’s view on this; Arendt’s suggested explanation for Disraeli’s Jewish exhibitionist behavior is now part of a well-trodden path. In his biography of Disraeli, Columbia University scholar Adam Kirsch says that to find a way to be both English and Jewish, he “had to convince the world, and himself, that the Jews were a noble race, with a glorious past,” turning “his Jewishness from something generally considered disgraceful and embarrassing into a strength.”

In Benjamin Disraeli: The Fabricated Jew in Myth and Memory, Bernard Glassman also agrees that Disraeli exploited his background to demonstrate the nobility of his ancient heritage and the superiority of his ancestral origins over those of his opponents: “Rather than deny his roots, he chose to make them an integral part of his mystique.” In Disraeli’s Jewishness, an anthology of essays edited by Todd Endelman and Tony Kushner, Endelman says his Jewish obsession “constituted a bold, if unusual, strategy to combat his own sense of special inferiority as an outsider in aristocratic Tory circles.”

But in that anthology, Kushner cautions that Disraeli’s parading his Jewish pride is “perhaps in danger of being overstated at the cost of many other features that made up this remarkable figure.” And Glassman asserts that, although Disraeli’s support of Jewish causes was “problematic,” his growing prominence attracted the admiring attention of Anglo-Jews who needed a hero to validate their own Englishness, and that gradually, in spite of Disraeli’s baptism, English Jews (numbering around 50,000 at the time) accepted him as a true representative of their faith and culture. Louise de Rothschild, a member of the famous Jewish banking family and a contemporary of Disraeli, was recorded to have said she felt “a sort of pride in the thought that he belongs to us, that he is one of Israel’s sons.”

Such exculpation does not impress Cesarani, who makes very few references to anything positive in Disraeli’s relationship to Judaism. He concludes his study of Disraeli with a further harsh assessment of his subject: “Ultimately, he fits squarely in modern Jewish history for the worst of reasons: he played a formative part in the construction of anti-Semitic discourse.” Disraeli’s racial stereotyping of Jews became part of the foundation of a prominent theme in modern anti-Semitic writings and speechifying by figures including Adolf Hitler. “At best,” says the implacable Cesarani, Disraeli “was a tragic, transitional figure; at worst, he was a reckless egoist.”

Norman Gelb is a London-based historian and author. His most recent book is Herod the Great: Statesman, Visionary, Tyrant.

3 thoughts on “Book Review // Disraeli: The Novel Politician”

It is an alarming tendency of modern “historians” to ignore the larger themes and fix instead upon the threads or minor points and then use those threads to upend everything everyone else had ever had to say on the subject. Disraeli was a politician and a masterful one at that. Of course he viewed people and policies as chess pieces to be moved about. Has any great man who ever achieved success in public life done otherwise? He served England in a time when the power of the nobility was being diluted and the middle class was rising. He wisely played up his “aristocratic” origins when it served him and kept silent when it didn’t. In the end, he left England better than he found it. The testimony of the Jews of his own day is a more trustworthy indicator of the truth of the matter than the quibblings of a historical revisionist.

Whether conversion is a matter of survival, as it was for Jews in 14th- and 15th-century Spain; a bid for economic and social mobility, as it was for David Ricardo, Benjamin Disraeli, Felix Mendelssohn and Gustav Mahler, to name just a few; or motivated by sincere belief, as it was for Jean-Marie (born Aaron) Lustiger, Archbishop of Paris from 1981 to 2005, who proudly described himself as a Jew; these converts were, in the end, viewed as suspect by many of their adopted faith as well as many gentiles.

“I am thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world. Everywhere an intruder, never welcomed.” Gustav Mahler

To be Jewish is to belong to a club from which no one is allowed to resign.

Fat finger alert:

“…as many gentiles.” Gentiles, of course, should be Jews.

Sigh