Europe Against the Jews: 1880-1945

by Götz Aly, translated by Jefferson Chase

Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt

& Company, 400pp., $32.99

There are many ways to explain the Holocaust. But not many historians have proffered a different theory with each published book. German historian Götz Aly is among the most innovative, provocative and knowledgeable experts on the Holocaust—and never shy about offering explanations of how it was possible that the Germans launched their ruthless war against the Jews. Aly has become famous for pursuing such grand explanations. A former activist in the Maoist branch of the 1968 student movement, Aly subsequently turned into a sharp critic of the student revolt. Now a respected journalist and public intellectual in Germany, he is one of the most widely read historians of the Holocaust. Aly’s early work ascribed a central role to a murderous bureaucracy becoming unstoppably entangled in first expelling, and then killing, the perceived enemy. In some of his later works, he focused on Germany’s population policy as the driving force in eliminating Jews and other people of “inferior races” to create room for a “nation without space.” In Hitler’s Beneficiaries (originally published in Germany in 2005), greed and the hunt for the property of the Jews turned ordinary Germans (and their ordinary helpers across Europe) into deadly beasts. His latest explanation, in Europe Against the Jews, is ethnopolitics: the need of the modern nation-state to cleanse itself of disturbing minorities.

To be sure, all of these theories are valid, up to a point. They all rely on the presumption that there has to be an entirely rational explanation for the Shoah. But what if there isn’t?

Even if we don’t buy the idea that one grand theory can explain the most systematic mass murder in human history, Europe Against the Jews provides much valuable material for further reflection. As the title suggests, the book is not an account of how the Germans killed the Jews, but rather of how a whole continent turned anti-Semitic well before World War II. Five of the seven chapters deal with prewar Europe and one with the postwar period, and anti-Semitism in Germany plays a much smaller part than anti-Semitic movements and actions in other countries, from Romania and Hungary to Greece and France.

Of course, the catastrophe that befell 20th-century Jewry was not without its prophets. Theodor Herzl founded the Zionist movement in 1897 because he had given up the hope that Jews, as Jews, would integrate into European societies. In The Jewish State, written in 1896, he admitted that he and his fellow Jews wanted nothing more than to be good citizens of their respective states, “if only we were left in peace…But I think we shall not be left in peace.” In a January 1, 1901 diary entry, Russian Jewish historian Simon Dubnow wrote, “We are entering the twentieth century.

What will it bring for us—for humanity and especially Jews? To judge from the final decades of the past century, it’s possible that humanity is heading toward a new Middle Ages full of terrible wars and national conflicts. But one’s soul resists believing that.” In a two-volume “history of the future,” published in 1901 and 1903, the lesser-known Bavarian Jewish author Siegfried Lichtenstädter even foresaw some details with astonishing clarity, including the rise of anti-Semitic violence, the German leadership declaring war on the Slavic peoples (in an entry for October 2, 1939), and the German occupation of Austria (April 1940).

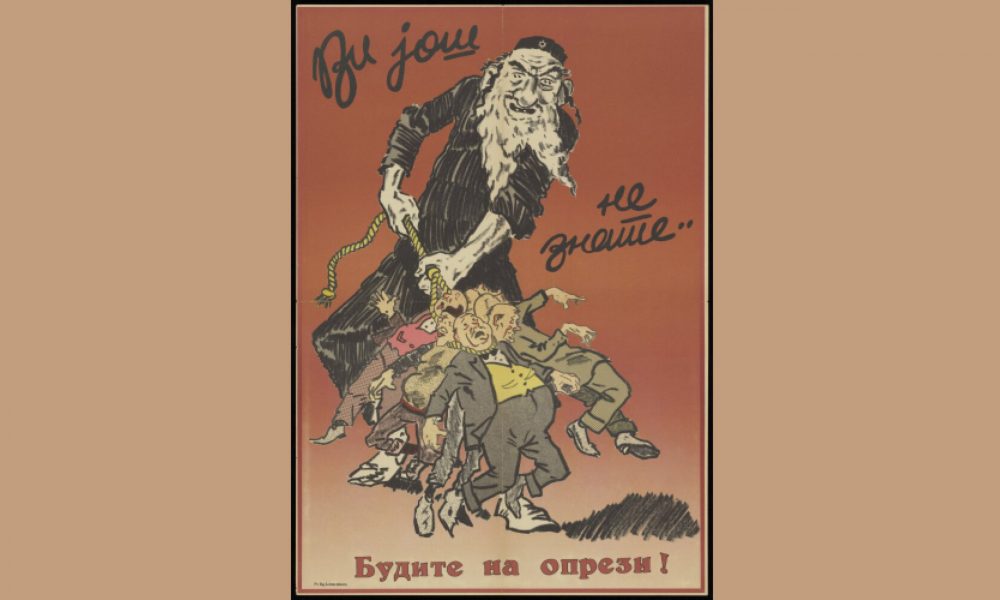

Serbian anti-Semitic propaganda poster “You Don’t Know Yet… Beware!” (1941). (Photo Credit: Courtesy of Blavatnik Archive Foundation).

We may add others to Aly’s list of prophets of doom. In the early 1920s, Vienna-based Hugo Bettauer predicted, in his best-selling “novel of tomorrow” entitled The City without Jews, the rise of an anti-Semitic leader who would expel all Jews from Austria. A few years later, his Berlin colleague Artur Landsberger wrote a remake focusing on Germany. Not that these authors had any solution to offer, nor were they able to save themselves once the real danger arrived. Bettauer was shot in 1925 by a right-wing extremist in Vienna; Landsberger took his own life in Berlin after the Nazis came to power in 1933. Dubnow, age 81, was shot in Riga in 1941 in a “mission” by the German Einsatzgruppe A and their helpers from the Latvian police. And 77-year-old Lichtenstädter was arrested in 1942 by the Munich police, was deported to Theresienstadt and died there shortly after. Despite their pessimism, none of them could foresee the full dimensions of the ultimate Jewish tragedy. Before Herzl died in 1904, he thought most European Jews would settle in the national Jewish homeland, while the remaining ones would completely assimilate into their respective nations, and anti-Semitism would disappear. Dubnow refused to leave Europe even after 1933 and continued to fight for Jewish autonomy in Eastern Europe. Bettauer and Landsberger both constructed happy endings in their novels, in which the Jews were entreated to return to their countries. Only in hindsight do we see the heavens continually darken over Europe.

Long before the Final Solution was on the table of the Wannsee Conference in January 1942, Aly writes, many European countries devoted time and energy planning how to get rid of their Jews. Already before World War I, the Russian Empire’s anti-Jewish policies contributed to the decisions by two million of its Jewish subjects to leave their homeland, mostly for North America. Until World War I, Romania refused to naturalize most of the Jews who lived in its territory, and with the Greek capture of Salonika from the Ottoman Empire in 1912, one of the most significant Jewish communities in Europe began its decline (since Greek nationalism identified only Orthodox Christians as true Greeks).

“The gas chambers of Auschwitz were not part of what ordinary Christians envisioned, but stripping Jews of their wealth and deporting them to destinations unknown certainly was.”

The aftermath of World War I brought about unprecedented anti-Jewish massacres in East Central Europe. Compared to the approximately 50,000 Jews killed in pogroms in the 1920s, the 50 victims of the 1903 Kishinev pogrom—until then the symbol for anti-Jewish violence—were but a pale memory. The creation of new nation-states after World War I only worsened things for the Jews, who—often along with other minorities—complicated the formation of ethnically homogeneous states. Hungary, Poland, Romania and the Baltic states introduced anti-Jewish legislation or failed to fulfill the demands of the postwar Allied powers to protect their minorities: They claimed Hungary for Hungarians, Poland for Poles and Lithuania for Lithuanians only. Ethnic homogenization was the aim, ethnic cleansing the means to achieve it. The Greek-Turkish population exchanges, the resettlement measures in Southern Tyrol and the expulsion of non-Hungarian minorities from Hungary were steps on the way to creating “genuine” nation-states. Jews stood in the way of this homogenization in almost all European states, just when the gates of possible destinations outside of Europe were closing as well.

In August 1920, the publisher of the New York daily Yiddishes Tageblat described the situation among Polish Jews as follows: “If there were in existence a ship that would hold 3,000,000 human beings, the 3,000,000 Jews of Poland would board it and escape to America.” Instead, the United States, formerly a haven for those unwanted Jewish masses in Europe, introduced restrictive immigration laws in 1921 and 1924. In the 1930s, as a reaction to increasing protests among the Palestinian Arab population, Great Britain gradually closed its doors to those Jewish emigrants eager to get to Palestine. When President Roosevelt in 1938 called for an international conference on refugees in Evian, France, many European delegates thought it actually would be an opportunity to discuss measures to get rid of their own Jewish population rather than take in foreign Jews. The only state volunteering to take in a substantial number of Jewish refugees was the Dominican Republic, whose dictator Rafael Trujillo was motivated by the possibility of “whitening up” the island’s population. European nationalists looked for more exotic destinations for their Jews: In 1933, Romanian nationalist Gheorghe Cuza received loud applause when he suggested Madagascar as a possible place for a “solution to the Jewish Question.”

“The gas chambers of Auschwitz were not part of what Hungarian politicians and ordinary Christians envisioned, but stripping Jews of their wealth and deporting them to destinations unknown certainly was,” Aly writes. Therefore, one should rather speak of “congruence of interests” than of “collaboration.” Hungarians, like Croatians, Romanians, Slovakians and others, realized that by assisting the Germans in deporting their Jewish population, “the war offered a unique chance to realize long-held plans for radical ethnopolitical action.”

Ethnopolitics is, without any doubt, one element in the extremely complex set of circumstances that led to the murder of European Jews. But like the other motives given by Aly in his earlier works, it cannot by itself explain the monstrosity of its implementation. One element remains conspicuously absent in Aly’s laudable attempts to explain what perhaps is not entirely explainable: ideology. There was always an irrational aspect in the way that some of the best German minds were declared unfit and driven out of the country, that German trains were used for deportations of Jews from Norway and Greece to Auschwitz rather than helping the war efforts of the Wehrmacht, and that Hitler’s last will, written after Germany was already defeated, was filled with anti-Semitic hatred. Purely utilitarian reasoning, such as ethnopolitics, settlement strategies and economic enrichment, can provide important but only partial explanations. A deep commitment to an ideology that often stood in conflict with those motives might add a dimension not fully explored in this and Aly’s other books. But given Aly’s prolific career as a Holocaust historian, perhaps this—combined with his earlier theories—will be the material for his next book and thus his crowning achievement.

Michael Brenner is the Seymour and Lillian Abensohn Chair in Israel Studies at American University in Washington, DC, and holds the chair of Jewish History and Culture at the University of Munich.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

One thought on “Book Review | Cleansing the Continent”

I don’t have high degrees (miraculously earned a B.A.) and I’m not very intellectual on most subjects. However, I have had numerous encounters with the God of Israel, the one true God. As I have tried to articulate many times in Moment’s blog, Jewish history begins and ends in the Bible. In 1985, during my first and most impacting encounter with God Almighty, the God of the Jewish and Christian Bibles (it’s really one), He spoke to me the most important words I ever heard or will hear. He said: “The whole Bible is truth, from Genesis to Revelation.” The reason I mention this in a Jewish blog, is that you cannot get the whole picture any other way. Not to be confused with conventional religious ideology, I’m talking about a book here. It is the only essential source of the truth and by the Spirit can be opened to anyone who inquires of God. As I mentioned, who am I that this is revealed to me? I just shared it with all who will hear.