Book Review // When Basketball Was Jewish: Voices of Those Who Played the Game

Hebrew Hoop Dreams

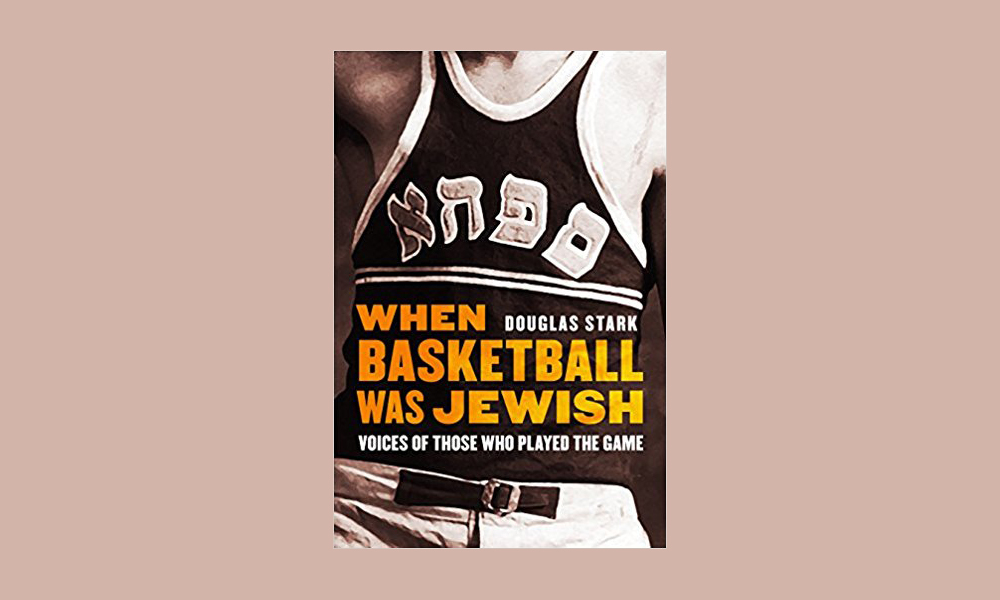

When Basketball Was Jewish: Voices of Those Who Played the Game

Douglas Stark

University of Nebraska Press

2017, 301 pp, $29.95

In Farewell to Sport, published in 1938, the popular New York Daily News sports columnist Paul Gallico, when departing the world of sports to write fiction (The Poseidon Adventure later became one of his best-sellers), reflected on the wide variety of sports and sports figures he had covered. About basketball, he wrote:

“Curiously, it is a game that above all others seems to appeal to the temperament of Jews, and for the past years Jewish players on the college teams around New York have had the game all to themselves…but the reason, I suspect, that [basketball] appeals to the Hebrew with his Oriental background is that the game places a premium on an alert, scheming mind and flashy trickiness, artful dodging, and general smart-aleckness…”

Gallico, to be sure, did not put a premium on avoiding ignorant stereotypes.

Without acknowledging Gallico—perhaps even unaware of his viewpoint—Joel “Shikey” Gotthoffer, one of the standout Jewish basketball players in the 1930s, echoes this perspective when recalling the rise of Jewish basketball players in another context:

“In my era, there were many good Jewish players. This is just my own theory. Jews by the very nature of the fact that they were constantly under some kind of pressure had to do a lot of thinking and developing of the mind in order to be able to live in society and act in society. And since there was so much hatred attached to them, they had to be able to outwit a person. And I think knowing that these kinds of conditions existed that you just acquired these things as you grew up…”

Gotthoffer is one of 20 players from the 1920s to 1960 featured in the oral history When Basketball Was Jewish: Voices of Those Who Played the Game, compiled by Douglas Stark, the author of several other books related to basketball. Basketball was invented in December 1891 by Canadian-American physician and chaplain Dr. James Naismith in the Springfield, Massachusetts YMCA. Within a relatively few years, Jews began to be represented in great numbers, most famously in the 1920s by the basketball star Nat Holman and his renowned Original Celtics team.

Invariably, stories of the men related in the book have a similarity, beyond the ubiquitous black knee guards, from Holman to the 1930s with Gotthoffer and Jack “Dutch” Garfinkel playing for the equally terrific Philadelphia SPHAS, to standouts in the early National Basketball Association, including Ossie Schectman (who in 1946 scored the first basket in NBA history, with a fast-break layup for the New York Knicks versus the Toronto Huskies) and stars of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s such as Ralph Kaplowitz, Sonny Hertzberg, Jerry Fleishman and the Knicks’ all-stars Max Zaslofsky and Dolph Schayes. Schayes was the lone Jew named as one of the NBA’s 50 greatest players on the league’s 50th anniversary in 2006. I once asked Sandy Koufax—who himself had gotten a basketball scholarship to the University of Cincinnati in 1954—if Hank Greenberg, the Hall of Fame baseball player and, like Koufax, a New Yorker, was his hero. “No,” said Koufax, “Max Zaslofsky was.”

The similarity the men shared was one of dedication, environment and, well, talent. To a man, they were from immigrant families and grew up either poor—having, for example, to share a bathroom in the tenement hallway with other families—or at least lower middle class, in either Brooklyn, the Bronx, the Lower East Side of Manhattan or Philadelphia. They fell in love with the game from an early age, playing in settlement houses, community centers or playgrounds and schoolyards. “The game was for poor people. So we played basketball from morning to night,” said Louis “Red” Klotz. Added Gotthoffer: “I can’t recall when I didn’t go to school dressed underneath with my basketball things so that at three o’clock I could stay in the playground and play basketball.”

These players moved on to starring in high school and at colleges such as City College of New York, Long Island University, St. John’s, New York University and Temple. Then some found professional ball, from playing in “cages,” as they were called—a chicken-wire netting from floor to ceiling that separated the spectators from the court—to games in ballrooms where dances would be held at half-time to arenas like Madison Square Garden. In the beginning, pro basketball was a weekend sport, with players making as little as $35 a game (no salaries) or thereabouts, which allowed the players to keep regular paying jobs during the week.

Although Jews in the East did have a remarkably high percentage of basketball players on the college and pro levels in the early and mid years of the game, it is a misnomer to state “When Basketball Was Jewish.” The game was played brilliantly, for example, by the New York Renaissance and Abe Saperstein’s Harlem Globetrotters (when serious), both famous black teams, as far back as the 1920s, as well as non-Jews such as the Original Celtics’ Joe Lapchick. The game was played so well in the 1940s by Midwesterners at the University of Illinois that its starting team was called “The Wonder Five.” And in the West, Hank Luisetti of Stanford in the late 1930s changed the nature of offense from two-handed set shots to his innovative running one-handed shot, an early version of the jump shot. These examples, to the credit of the players in the book, are extolled in their stories.

But the game for Jews changed as black players were given greater opportunities in college and in the pros and excelled. Foreign-born players became more prevalent on American rosters. Today, there are Jewish players scattered on teams around the country, but the domination of a Jewish presence is seen primarily on coaching staffs and in team ownership and administration.

Stark did some of the interviews himself, while others were culled from oral recollections in archives such as those from the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the American Jewish Committee. The book would have been helped with tighter editing, since it has numerous repetitions and misspellings of names. The 1951 college point-shaving gambling scandals, which involved a host of Jewish players—including seven from Coach Nat Holman’s CCNY team that had won both the NIT and NCAA championships in the same season, 1949-50—receive scant attention in the book. (Twenty-nine players from six schools were convicted of sports bribery.)

Holman, who was cleared of any wrong-doing but nonetheless was devastated by the scandal, may be best known as the first great basketball player—not just the first great Jewish player. He was once known as “Mr. Basketball.” I interviewed him in the Hebrew Home for the Aged in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, in 1992, when he was 95. White-haired and natty in a pinstriped suit, he sat on his bed, a cane beside him. As to the scandals, he said, “They were good boys, you do whatever you can for them, and if the boys don’t do the right thing, then they must suffer the consequences.”

The last time Holman held a basketball, he said, was the year before I saw him—he was describing fundamentals to a group in a gym.

I asked if he took a shot. “Yes,” he said. I asked, “Did you make it?” He gave me a sideways look: “Are you kidding?”

He stood up. “You know what I’d like?” he said. “A corned beef sandwich for lunch.”

Read more about Jews in Sports

Ira Berkow is a Pulitzer Prize-winning former sports columnist for The New York Times. He has written several books on basketball, and his most recent book, It Happens Every Spring, is a collection of his baseball writings.