Book Review | Angels of Death on Trial

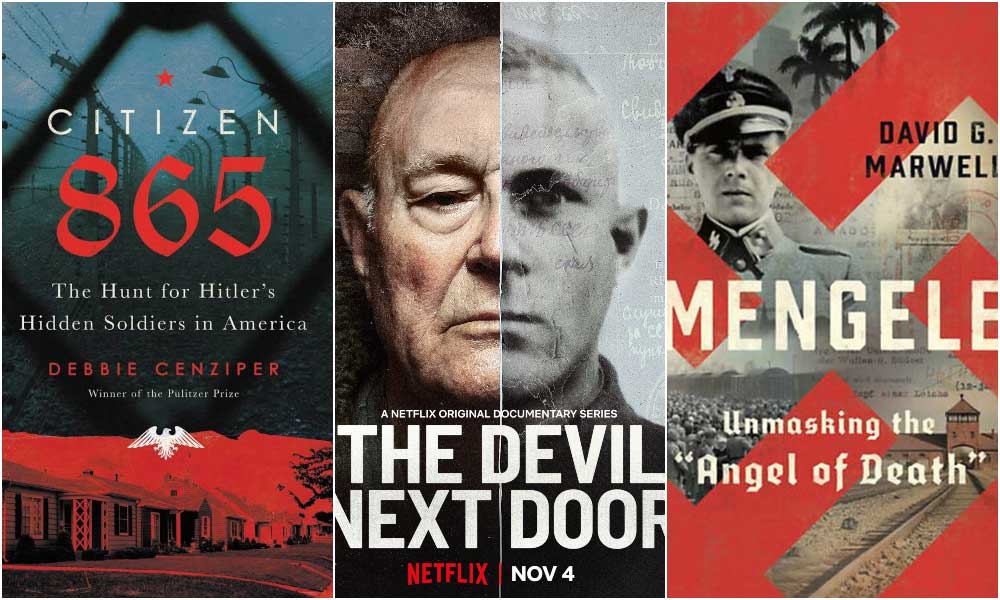

Mengele: Unmasking the Angel of Death

By David G. Marwell

WW Norton, 448 pp, $30.00

The Devil Next Door

Directed by Yossi Bloch and Daniel Sivan

Netflix, 2019 (5 episodes)

Citizen 865: The Hunt for Hitler’s Hidden Soldiers in America

By Debbie Cenziper

Hachette, 320 pp., $28.00

Dr. Josef Mengele, physician, anthropologist, son of a prosperous Bavarian family, Nazi Party member, anti-Semite and SS officer, was one of the concentration camp doctors at Auschwitz. Like the others, he took part in the “selection” of new inmates. In brief assessments, as they came off the trains, Mengele decided who would live and who would die. Those fit enough to work at the camp for the time being had death deferred. Those evidently weak or unwell were sent to their deaths forthwith.

Some of the new arrivals were spared: medical doctors or pharmacists whose training made them valuable either as camp medical staff or as contributors to Mengele’s notorious genetic research projects. His experiments on living subjects—injecting dye into their eyeballs, for example, to study eye color—reflected a complete indifference to the humanity of camp inmates, both Jews and Roma. From the freight cars, he saved some prisoners whose conditions from birth—twins, dwarfs—were of sufficient scientific interest to him to be subjects of those projects. He was known to inmates as “the Angel of Death.”

“Ivan the Terrible” was the sobriquet of the camp guard at Treblinka who slashed, stabbed and clubbed Jews as they entered the gas chamber that he operated. Unlike Auschwitz, Treblinka was not part death camp, part labor camp. Its mission was extermination plain and simple, and the opportunity for survival was minimal. Those few who managed to survive recalled Ivan as an especially sadistic Ukrainian (Ukrainian POWs and other Soviet minorities captured from the Soviet Red Army were a source of manpower for the German plan to exterminate the Jews). Lacking the rank and profession of a Mengele, and given the purpose of Treblinka, he was not a disburser of reprieves, nor the issuer of death sentences. He was simply an executioner and, according to survivors, an enthusiastic one.

From a ramp near where they came off the trains to the almost certain place of their death, in brief assessments, Mengele decided who would live and who would die.

Both men achieved a level of infamy unusual even among Nazi war criminals, for reasons evident in two new treatments of their lives and deaths: David G. Marwell’s biography of Mengele and Netflix’s five-part documentary series on the trials of John (born Ivan) Demjanjuk. Both men were perpetrators of the Holocaust who escaped justice in postwar Europe and survived in countries where tolerance of anti-Communist refugees, especially in émigré communities, ran high. Mengele lived first in Argentina, then in Paraguay and, finally, in Brazil; Demjanjuk in Ohio. Their freedom was a reproach to Holocaust survivors at a moment when time was thinning the ranks of witnesses and when survivors were increasingly speaking out as a group, no longer silenced by a sense of shame at having escaped the fate that claimed their parents and siblings in the camps. In June 1981, I covered the first World Gathering of Holocaust Survivors and their children in Jerusalem for National Public Radio. Although such an event may have seemed normal a few years later, it was novel at the time, and the engagement of the children promised that the unfinished business of prosecuting crimes of the Holocaust would be pursued in the future.

Pursuing that unfinished business in court decades after Germany’s defeat was not easy, and it raised more issues than might have been anticipated in those early days—issues of global politics, the limitations of forensic science in the 1980s and, perhaps most painfully, issues of certainty, doubt and due process. Typically, the U.S. government’s strategy was to locate postwar refugees from Central and Eastern Europe who had lied to immigration officials about their wartime pasts. Then, the job was to strip them of citizenship and have them deported—to countries where they could be prosecuted further, whether in Israel or in the Eastern Bloc nations where they had been born. It was a little like prosecuting Al Capone for tax evasion. Another new book about Nazi hunters, Debbie Cenziper’s Citizen 865, captures the difficulty when she quotes Allan Ryan, the original chief of the Office of Special Investigations (OSI), the Department of Justice unit that was set up to pursue these cases. Ryan warns his staff that no federal judge would deport an elderly, law-abiding immigrant for false information on a visa application: “These are war-crimes cases,” he said. “These are not immigration cases.” That they literally were immigration cases is a measure of how awkwardly criminal remedies applied to more-than-just-criminals like Ivan the Terrible and the Angel of Death.

Jewish twins kept alive in Auschwitz for use in Mengele’s medical experiments. (Wikipedia)

Investigators battled one type of uncertainty in June 1985 when they exhumed (very clumsily, as Marwell describes) the remains of Josef Mengele, who died in a 1979 swimming accident off a Brazilian beach and was buried under an alias. In an era when DNA identification was in its infancy, three governments—the United States, West Germany and Israel—would argue for at least seven years over whether the bones were proof that the Angel of Death was actually dead. Some prominent survivors, Nazi hunters and Israeli investigators held out against the burden of the evidence, and their political significance in government and media circles added weight to doubts that might otherwise have been dismissed as unfounded.

The possibility of Mengele’s survival inspired rage and fear—and more than a little political opportunism. In Senate hearings, Alfonse D’Amato, a New York Republican who had taken up the issue despite being better known for ward-heeling than for war crimes investigations, expressed skepticism about the conclusion of forensics experts that Mengele was dead. Marwell describes the leader of the group called CANDLES (Children of Auschwitz Nazi Deadly Lab Experiments Survivors) criticizing him and other investigators who accepted Mengele’s identification. “She alleged,” he writes, “that those involved in the investigation, never having dealt with Nazis, had been hoodwinked by the testimony of those who had helped Mengele in Brazil.” The understandable desire to find Mengele alive and try him, presumably on television, contributed to a reluctance on the part of some to accept the fact of his death—which was ultimately confirmed by an early forensic use of DNA.

Marwell is a historian who served on the Justice Department’s OSI team, and his book reads like the authoritative final report of an effort that consumed several years of his life. One important point he makes is that some of Mengele’s actions that were initially seen as cruelty and sadism above and beyond the call of duty—dispatching the severed head of a child to Berlin, for example—were very much in keeping with the institutionalized cruelty of German science in the Nazi era. He was providing samples to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, samples much appreciated by senior researchers who lacked the kind of access to a large research population that Auschwitz afforded their fellow scientist. The German Society for Physical Anthropology had changed its name in 1937 to the German Society for Racial Research. Of Mengele’s decision that same year to join the Nazi Party, Marwell writes, “Mengele’s commitment to Nazi ideas and wholehearted support of the movement arose through the science that was to occupy him in the next years of his life.” This does not mitigate Josef Mengele’s guilt for crimes against humanity, of course, but it does place him within an organized crime family of academicians to whom he reported and who were complicit in those selections, even if physically far from the ramp at Auschwitz.

Josef Mengele (Wikipedia)

Marwell’s account is an adventure in pathology and criminology, based on Mengele’s own letters and writings, archival materials and medical records, as well as reports released by the CIA in 2000 and by the Mossad in 2017. Bizarrely enough, Mengele not only kept diaries but also wrote a thinly veiled autobiographical novel while living incognito in South America, a work that, he wrote to his son, was about a man “shaped in a very special way by his time.” According to Marwell, Mengele went to his Brazilian grave unrepentant, convinced that his actions had been justified by the context of the era. In an investigative tour de force, Marwell managed to put together Mengele’s real-life alias and the name of a character in his novel to deduce the likely name of the real-life German Army doctor who had given Mengele a duplicate of his own discharge certificate—a document that protected him from prosecution in postwar Germany.

The book also shows how the same evidence can look very different to different investigators. Mengele’s son Rolf barely knew him, having been raised by a stepfather, and came to find his father’s past deeds repugnant. After Mengele’s death, Rolf’s question to a family friend as to whether what his father had done would have merited a war crimes trial was misread by Israeli investigators as evidence that Mengele’s death was likely faked and that his son was still concerned about a trial. It was, in fact, a son’s effort to measure the enormity of his father’s crimes.

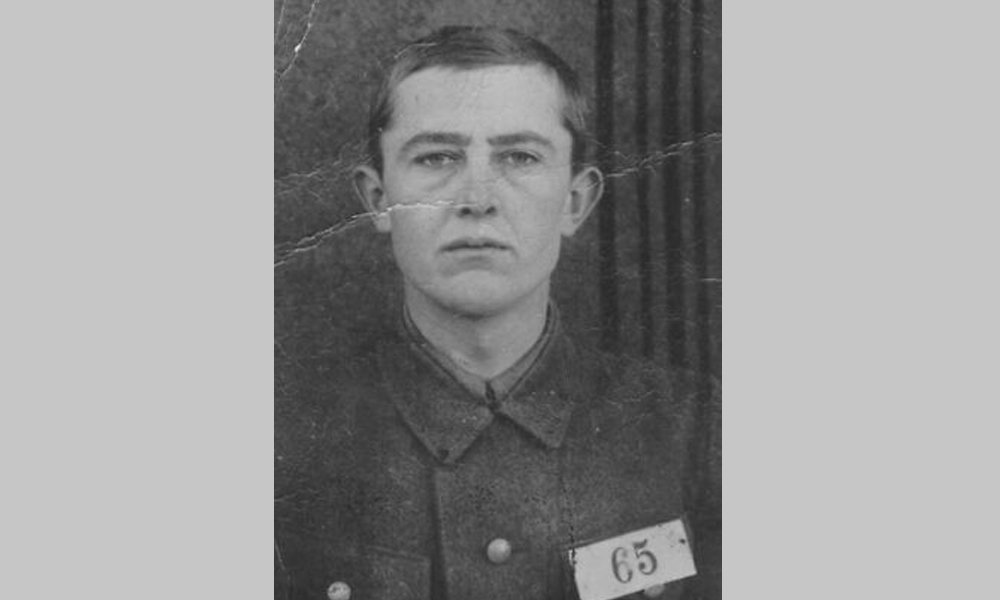

Jack Reimer (U.S. Department of Justice)

The many years of debate over the identity of Mengele’s skeleton were greatly exceeded in length by the litigation over whether the Ukrainian immigrant auto worker from suburban Cleveland, John Demjanjuk, was, as accused, Ivan the Terrible of Treblinka. Unlike in the case of Mengele, the doubt in this story was never completely dispelled. Identified by investigators in 1977 when he was 57 and living in Cleveland, Demjanjuk claimed that, as the Germans’ prisoner of war, he had been coerced into his service at the camps and that he had never served at Treblinka. For lying about the time he did serve at Nazi camps, he was deported to Israel to stand trial. Demjanjuk’s trial there, in 1987 and 1988, was likely akin to what Mengele would have faced had he been found alive and extradited: live radio microphones and television cameras, a courtroom audience of Holocaust survivors and a few Demjanjuk relations, a spectacle that warranted the unfortunate label “show trial.” The Netflix documentary is enlivened by television footage of nearly every step in the story, from the time Demjanjuk was first accused until his death in 2012 in Germany.

The understandable desire to find Mengele alive and try him, presumably on television, contributed to a reluctance on the part of some to accept the fact of his death.

There were troubling gaps in the evidence. One prosecution witness who identified the defendant as Ivan the Terrible was subsequently revealed (by a Nazi hunter) to have signed an affidavit in 1947 describing how he had taken part in Ivan the Terrible’s murder during an inmate uprising at Treblinka. Another, asked how he had once gone from Czestochowa in Poland to testify in a different proceeding in Florida, replied, “By train.” A prosecutor interviewed years later for the documentary dismisses such flaws as understandable memory lapses of elderly witnesses under great stress. Another member of the prosecution team expresses contempt for the enthusiasm of Demjanjuk’s Israeli defense lawyer—as though it were the defense counsel’s task to defend him less than vigorously or to ignore holes in the government’s case.

There were other inconsistencies. Early in the trial, the prosecution relied on Soviet documents from the time of liberation, which the defense disputed as forged propaganda designed to drive a wedge between anti-Soviet Ukrainians and anti-Soviet Jews. Later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the opening of KGB archives, it was the defense that relied on Soviet documents and the prosecution who questioned their authenticity. Worst of all, the OSI prosecutors were found to have seen evidence that cast doubt on Demjanjuk’s having served at Treblinka and failed to share that with his defense.

John Demjanjuk (Wikipedia)

The trial, which resulted in a conviction that was overturned by the Israeli Supreme Court, demonstrated the odd fit of 40-year-old war crimes and criminal law as practiced by the standards we would all hope to face in court. In the end, Demjanjuk was convicted by the Germans in a separate trial for having served as a guard at several concentration camps. The case was precedent-setting: It led to other trials of guards whose work at a death camp was deemed criminal per se, regardless of their individual actions on the job. What was never proven was that John Demjanjuk was Ivan the Terrible of Treblinka.

These two cases of disputed identity, one living and one post mortem, fell into the most inopportune era from the standpoint of the investigators. By the 1980s and 1990s, surviving witnesses to the crimes committed at Auschwitz and Treblinka were aging, and the passion to prosecute was in inverse proportion to the strength of their testimony. Tracking their fugitives, Marwell and his colleagues seem like slow-motion gumshoes when viewed from these days of digitized databases, search engines and social media. The priceless cutting-edge intervention of Sir Alec Jeffreys, discoverer of the DNA fingerprint, finally identified Mengele with the kind of genetic data we can now buy retail from the likes of Ancestry.com or 23andme. Technology aside, what should have been the most promising years for investigation, shortly after the war, were further frustrated by Cold War politics. The Soviet Union kept its archives closed; the United States was loath to deport anyone to the Soviet Union.

On a different note, investigative journalist Cenziper’s Citizen 865 recounts the OSI’s successful effort to strip Jack (born Jakob) Reimer of his U.S. citizenship. Reimer lacked the monstrous reputation of Mengele or Ivan the Terrible. In fact, he had never guarded Jewish prisoners. An ethnic German from Ukraine who became an officer in the Red Army, Reimer, like Demjanjuk, was taken as a POW by the Germans and sent to an SS training camp in Poland called Trawniki. Marwell’s colleague at OSI, historian Peter Black, spent years studying Trawniki and its role in the Holocaust. Ukrainians and other Soviet minorities who were sent there were given uniforms, salaries and—in Reimer’s case—promotions and vacation leave in exchange for committing and abetting the mass murder of Polish Jewry. Reimer admitted in an interrogation to having been present at a massacre of Jews and firing one shot, under orders from a German, at one desperate survivor in a ditch full of fresh corpses. By the time Black and company had found documents to corroborate his presence at the scene and take Reimer to court, the accused was pushing 80, retracted his story and went before a federal judge whose initial request to OSI Director Neal Sher was the one that Sher’s predecessor Allen Ryan had foreseen: “I don’t suppose that I can convince you to leave this poor old man alone.”

Ultimately, Reimer lost his citizenship, but with Germany unwilling to take him back (he had actually been granted German citizenship during the war), he died in Pennsylvania in 2005, having lived largely undisturbed in the U.S. for half a century. It’s a reminder that justice did not always win out in the pursuit of Nazis and their helpers. Time proved invincible.

And indeed, these new accounts full of courtroom footage (in the case of Demjanjuk), interview transcripts (in the Reimer story) and candid first-person recollections (by Marwell) are a chance to revisit and perhaps review an era that is now behind us. So how well did judges and prosecutors do in the roundup of hidden war criminals? Was the enterprise a success?

The argument over the value of bringing Nazis to trial dates in earnest from 1961. That year, the film Judgment at Nuremberg lionized the postwar trials of Nazis and won Academy awards, and Israel prosecuted Adolph Eichmann in Jerusalem in what Hannah Arendt famously condemned in The New Yorker as a show trial—of which, she wrote, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion was “the invisible stage manager of the proceedings” and prosecutor Gideon Hausner his obedient servant, keeping the trial away from historical questions that Arendt thought needed answering, and heaping blame on the unremarkable careerist in the glass booth. But Arendt’s take, though influential, was not the only one. In 1990, Hausner died and the Israeli writer Shulamith Hareven wrote an obituary in praise of him and the decision to hold the trial that had made him famous. “Eichmann could have been shot down on the spot,” she wrote. “Such things have happened. One bullet and the murderer is no more. Except that, actually, there is nothing in such a deed. Murder a criminal in secret and it is as if nothing has happened. No facts come to light. Nothing is learned. In essence, nothing changes.” Hareven recalled how most Israeli survivors in 1961 were reluctant to relive the horror, to confront public disbelief or contempt for their not having resisted. But the communal experience of the trial changed that, legitimizing and encouraging the stories of witnesses.

In later years, the pursuit of lower-level participants in the mass murder of European Jews fed, and fed off of, a similar openness, fueling a pursuit of justice even when there was doubt—as there never was for Eichmann. The role of doubt isn’t satisfied by these accounts, which raise other troubling questions: Does our willingness to let a defendant go free diminish because of the magnitude of his alleged atrocities, despite reasonable doubt raised by an ardent defense? Do the same atrocities paralyze our judgment with doubt when the evidence says that the Angel of Death is dead?

Former NPR senior host Robert Siegel is a special literary correspondent for Moment.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

One thought on “Book Review | Angels of Death on Trial”

HOW many know anything about the crusades ????