For nearly 1,000 years, Cairo’s Karaites guarded one of the world’s most Legendary Hebrew manuscripts. Thirty years ago, it vanished…

Part I: Guardians of the Codex

In 1978, J. Zel Lurie, a veteran reporter and the founding editor of Hadassah Magazine, traveled to Cairo on a TWA Airlines junket promoting direct daily flights to Egypt from JFK. It was an exhilarating time: Egypt and Israel had recently signed the Camp David Accords, forging a historic peace, and Lurie was there to see what was left of the country’s once-vibrant Jewish community. The few remaining Jews showed their visitor a dozen or more synagogues, most of which had stood empty since the departure 20 years earlier of most of their brethren.

While in Cairo, Lurie was contacted by a representative of an ancient Jewish sect known as the Karaites. The Karaites had lived in the city for more than a millennium, and their numbers, too, had dwindled. The man asked Lurie to photograph a few pages of an old manuscript at a synagogue he had not yet visited and to deliver the photographs to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “He had heard I was going on to Israel,” says Lurie, then in his 60s and now a sharp 102-year-old living in Delray Beach, Florida. Lurie, who had gotten his start in journalism at pre-state Jerusalem’s Palestine Post, agreed.

And so, camera in hand, he found himself at the Moussa al Dar’i synagogue, an imposing domed edifice on Sebil el Khazindar Street in Abbasiyah, a relatively new section of Cairo. “I climbed a narrow stairway to the Karaite sanctuary, which was like a mosque,” he recounts. “It only had a few seats in the back.” Rugs were spread out over the floor for prostrating worshippers. There, Lurie met Ferag Menashe, the man who had contacted him. He was the shamash—the sexton—of the synagogue, and he led Lurie into a small room next to the altar. In it stood a five-foot-tall wooden cabinet, its shelves laden with manuscripts.

Ferag Menashe holding the Cairo Codex in the Moussa al Dar’i Synagogue in Cairo, 1977.

J. Zel Lurie in 2015.

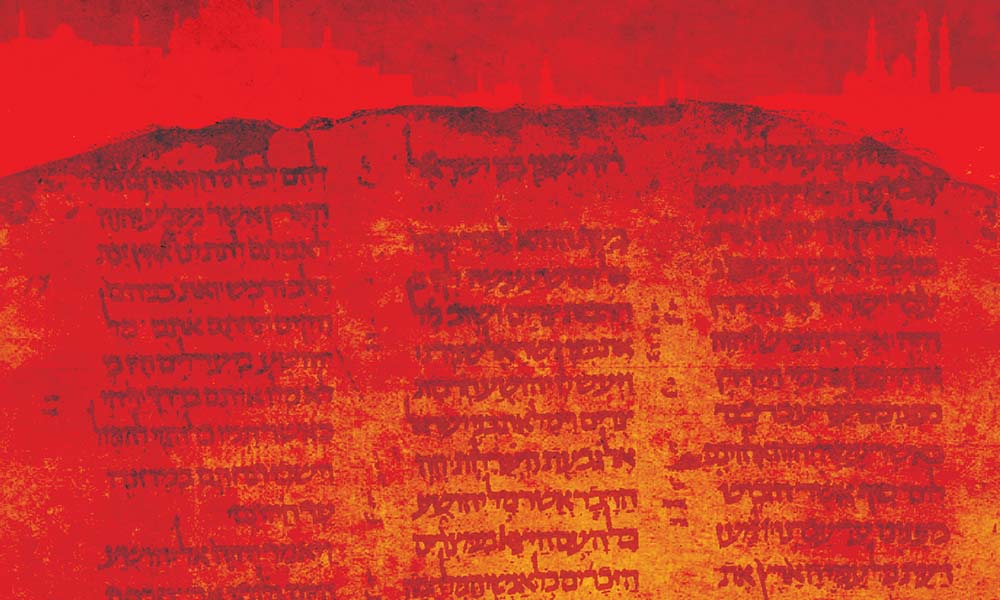

The shamash was interested in one manuscript in particular. “Its cover was broken up and it needed repair,” Lurie recalls. Its 567 pages were made of gazelle-hide parchment that measured 16 by 15 inches, and most were inscribed with three columns of gracefully handwritten Hebrew. Menashe showed Lurie the manuscript’s illuminated pages. These were decorated with meticulous micrography: delicate lines of tiny Hebrew letters spelling out biblical phrases that formed complex geometric patterns, interlaced with color and overlaid with gold leaf. Menashe told Lurie they had never been photographed in color, and held them up to the camera one by one. Though not a sentimental man, Lurie was moved by their beauty. He counted 13 carpet pages, a term used for illuminated pages. The shamash told him there had been one more, but it had been stolen.

These pages belonged to the legendary Cairo Codex—originally known as the Codex of the Prophets. Until that day, Lurie had never heard of the manuscript, which had been in the possession of Karaites in Cairo for nearly 1,000 years. Decades later, the pages would become an obsession, but by that time, it would be too late. The illuminated pages—and the entire manuscript—had vanished.

The history of the Cairo Codex is deeply entwined with that of the Karaites. In the century after the Romans sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE and the Second Temple was destroyed, Judaism was in flux, and the influence of rabbis on practice and interpretation grew. In Baghdad, a group of Jews rebelled against the rabbis’ authority. They would eventually become known as Karaites, which comes from kara, “to read” in Hebrew. Karaites did not subscribe to the rabbinical interpretations of scripture that are the foundation of modern Judaism: They were the original originalists, striving for the meaning that would have been understood by the ancient Israelites. They followed a pre-rabbinic calendar of holidays and had very different rules about what is kosher and how to observe Shabbat.

The history of the Cairo Codex is deeply entwined with that of the Karaites. In the century after the Romans sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE and the Second Temple was destroyed, Judaism was in flux, and the influence of rabbis on practice and interpretation grew. In Baghdad, a group of Jews rebelled against the rabbis’ authority. They would eventually become known as Karaites, which comes from kara, “to read” in Hebrew. Karaites did not subscribe to the rabbinical interpretations of scripture that are the foundation of modern Judaism: They were the original originalists, striving for the meaning that would have been understood by the ancient Israelites. They followed a pre-rabbinic calendar of holidays and had very different rules about what is kosher and how to observe Shabbat.

Karaites considered themselves the true Jews and considered “Rabbanite” Judaism to be a Roman-influenced corruption, while rabbinical authorities generally viewed Karaites as heretics. Despite their standing, the Karaites played a significant role in the evolution of Jewish scripture. Very few scrolls containing the Hebrew Bible, known as the Tanakh in Hebrew, survived the destruction of the Second Temple. From the 8th to 10th centuries, anti-Rabbanite scribes in Tiberius, then the center of learning in Palestine, copied the surviving scrolls, preserving what is called the Masoretic scripture—the vowels, punctuation and cantillation markings needed to vocalize and chant the text, as well as notes in the margins about such details as spelling. The scribes took advantage of new technology, composing their Bibles on animal skins cut into pages and forming them into manuscript books. These were called codices, and each took years to create. The skins had to be prepped and trimmed, pages ruled, text written, markings inserted, notes added, illuminations made. Even a team working together could produce only a few in a lifetime.

Lurie photographed these illuminated pages of the Cairo Codex in the Moussa al Dar’i Synagogue in 1978. In all, he photographed 13 pages, six of which appear here and throughout the piece.

The illuminated pages were decorated with meticulous micrography: delicate lines of tiny Hebrew letters spelling out biblical phrases that formed complex geometric patterns, interlaced with color and gold leaf.

One family of scribes was especially revered for its codices—in particular, the last of the line, Aaron ben Moshe ben Asher. His version of the Jewish text would become the model for scribes in the following centuries, painstakingly scrutinized by scholars—even today—who consider it the key to a deeper understanding of how the Bible, religion and language evolved over time.

The manuscript that Lurie saw in the cabinet in the Karaite synagogue in Cairo was called the Codex of the Prophets because it contained the section of the Bible that includes narratives of the prophets, from Joshua to Malachi. And according to the first and most important of its colophons—statements at the end of codices providing information about who wrote and commissioned them, and to whom they were given—it was commissioned by a rich Karaite and written in 894 CE by Moshe ben Asher, Aaron’s father, making it the earliest known Hebrew manuscript.

The Moussa al Dar’i Synagogue in Abbasiyah, Cairo in 1954.

The Codex was given to the Karaites in Jerusalem to keep in their synagogue but was seized by the Crusaders when they plundered Jerusalem in 1099. Additional colophons, added at later dates, continued the dramatic story. A wealthy Cairo Karaite, David Ben Yaphet, paid a vast sum to ransom it from the Crusaders, then gave it to the Karaite community in Old Cairo. Under their care, the Codex survived centuries of Fatimid, Ayyubid, Mamluk, Ottoman, French and British rule. It was an object of reverence read from and admired on the Sabbath and on special occasions such as the new moon, festivals and fasts.

The colophons also contained warnings. “This book is consecrated to the Lord of Israel in the Synagogue of Cairo,” one reads. “Cursed is he who sells it and cursed is he who buys it and cursed is he who would change its holiness and cursed is he who would pawn it.” Another reads: “Nobody shall be permitted to bring it out of the synagogue except if it is done—may God prevent it—by compulsion. One shall return it at the time of tranquility. Whoever changes this condition and this holiness shall be cursed by the Lord and all curses shall come upon him.” The Karaites took these admonitions very seriously. For hundreds of years, the Cairo Codex and many other ancient and medieval biblical manuscripts sat in the vaults of Cairo’s Karaite and rabbinical synagogues. But in the 19th century, modern Western biblical scholars and collectors began scouring the world for manuscripts, and Cairo was usually one of their first stops. Among the most sought after were those linked to the Asher family, which could be used as sources on which to base new editions of the Bible.

The Cairo Codex, kept at the Rav Simcha Synagogue in the Karaite quarter, was a beacon. The famous Palestinian Jewish traveler Jacob Saphir, English bibliophile Elkan Nathan Adler and Rabbi Pesach Finfer from Lithuania all examined the Codex, which Adler called “the most curious of all Karaite manuscripts.” In 1905, the noted Near Eastern scholar Richard Gottheil came from New York City to take inventory of the Rav Simcha vault and have a photographic reproduction made of the Codex as well as other manuscripts. “They were among the most magnificent specimens of the Hebrew penman’s hand that I have ever set eyes on,” he wrote in his treatise, Some Hebrew Manuscripts in Cairo, later that year. “One stands before these venerable monuments with feelings not unlike awe; immense masses of parchment….Think of the love, the veneration, the sacredness that are here embodied.”

Gottheil thought less of the Karaites who watched over the manuscripts. The volumes, he said, were looked upon with “great awe and intense superstition. They are regarded as amulets; but their real value is not appreciated.” He was infuriated by how the Cairo Codex was “stuffed” in a wooden box with a glass top, and other manuscripts were wrapped in handkerchiefs and rags, “with damp and mold eating their way through the parchment.” And yet on Saturday morning, he wrote, they “are covered in their repose with gold-embroidered velvet drapings and reverently kissed by worshippers.”

The Karaite who redeemed the Codex from the Crusaders could never have imagined that the community upon which he bestowed the Codex would survive so long in one place. By the beginning of the 20th century there were Karaites scattered throughout the Middle East and Europe, but the Cairo community was by far the largest. The years 1925 to 1948 were a golden age for Egypt’s Karaites and its Jews, who numbered about 5,000 and 75,000 respectively in 1948. But the good years came to an abrupt end with the establishment of the State of Israel, which set off a tidal wave of anger in Arab countries. In Cairo, anti-Israel rioters made no distinction between rabbinical Jews and Karaites, and on June 20, 1948 a bomb was thrown into the Karaite quarter, killing 22 and injuring 41. One thousand Karaites left that year, welcomed to Israel under the state’s Law of Return, though they were classified as a separate religion. The remainder stayed in Egypt, hoping life would return to normal.

Baruch Lieto Haroun unlocks the cabinet in which the Cairo Codex and other manuscripts were stored, 1977.

The interior of the cabinet in 1977.

It didn’t. In 1956, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power and radically curtailed the rights of both Jews and Karaites. The majority of rabbinic Jews were not citizens, and were expelled or left after the 1956 Suez War. Although most Karaites were Egyptian citizens, they were not exempt from persecution and internment. From 1948 through the 1967 Six-Day War, “many Karaites and Rabbanites were put into protective custody without trial or even interrogation,” according to the late Egyptian Karaite historian Mourad el Kodsi, author of the 1987 book The Karaite Jews of Egypt 1882-1986. The Karaite exodus continued, primarily to Israel, but also to Europe and the United States.

People fled, but their religious artifacts remained. By February of 1956, when the great German biblical scholar Paul Kahle realized a long-standing dream and came to see the Cairo Codex, it had been moved to the Moussa al Dar’i Synagogue, built in 1926. Nasser, it is said, had declared the Codex an Egyptian national treasure, and the community feared for its safety. In 1960, the same year that the director of the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, came to see the Codex, Egyptian authorities searched the synagogue. They “seized the opportunity to take an inventory of the vault,” on the pretense that the acting hakham—religious leader—was “hiding gold in the geniza,” writes el Kodsi in his 2004 book, A History of Two of Ben Asher’s Codices.

By 1970, only a few dozen Karaites were left in Cairo, and three served as the de facto guardians of the Codex. One of them was Ferag Menashe. The son of a highly respected former Karaite council member, Menashe was a proud Karaite who oversaw the community’s property as well as the cemetery at Basatin, southeast of Old Cairo. He also did double duty as the shohet, or kosher butcher.

The other two men held the keys to the cabinet in which the Codex was secured by a heavy metal bar held in place by two padlocks. Both men had to be present to open it. One was Elie Massouda, a retired government lawyer who was the president of the Karaite community in Egypt. The other was Baruch Lieto Haroun, a retired wool merchant who led prayers in the absence of a spiritual leader. The majority of the Egyptian Karaite community had re-formed in Israel, establishing new headquarters in Ramle, a small city south of Tel Aviv. The fate of the Codex largely lay in the hands of these men, all of whom have since died.

As Lurie would learn during his 1978 visit to the Moussa al Dar’i, the guardians of the Codex had far more than color reproductions of the carpet pages on their minds. They knew that the long Karaite chapter in Egypt was coming to a close, and that they would soon be departing for Israel. Eventually, Menashe told Lurie, the Codex would have to be smuggled out.

The illuminated pages were made of gazelle-hide parchment that measured 16 by 15 inches.

At the time, Lurie didn’t give this much thought. He took the film to Israel and had it developed. As requested, he dutifully sent copies of his slides to the Jewish National and University Library at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Back in New York, Lurie commissioned Rabbi Boruch K. Helman to write about the Karaites for Hadassah Magazine. Helman, now 77, had studied Arabic at the American University in Cairo in the 1960s and was a regular visitor to Cairo. He included a few paragraphs about the Codex, which he had seen on a visit to the Moussa al Dar’i along with soon-to-be Israeli Ambassador to Egypt Eliahu Ben-Elissar. The article was the cover story of the March 1979 issue. Once it was published, Lurie forgot about the Cairo Codex.

Lurie had lost interest, but the parade of high-ranking Jewish leaders making pilgrimages to see the Codex continued. One visitor was Greville Janner, then the president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews. According to a January 4, 1980 article in The Jewish Chronicle of London, Janner, who died this past December, saw the Codex in late 1979. He reported that some of its pages were discolored and stuck together.

Janner met with Anwar Sadat and secured permission for the Codex to be sent to London for repair. In the article, Janner reports that Sadat said “the Codex was a treasure that belonged not only to Egypt, but to the Jewish people,” and that it could go abroad for restoration and be put on exhibition. Afterward, Sadat expected it to be returned to Egypt. “It seems to me that the president’s request is a very reasonable one,” Janner told The Jewish Chronicle. “I am very pleased with his decision.”

Janner met with Anwar Sadat and secured permission for the Codex to be sent to London for repair. In the article, Janner reports that Sadat said “the Codex was a treasure that belonged not only to Egypt, but to the Jewish people,” and that it could go abroad for restoration and be put on exhibition. Afterward, Sadat expected it to be returned to Egypt. “It seems to me that the president’s request is a very reasonable one,” Janner told The Jewish Chronicle. “I am very pleased with his decision.”

The Cairo Karaites were not. In his A History of Two of Ben Asher’s Codices, el Kodsi mentions that “the rightful owners”—the Karaites—were not consulted or even mentioned in the Chronicle story. On January 27, 1980, an article, “Jewish Sect in Cairo Fights Removal of its Torah,” appeared in The New York Times. In it, the Karaites expressed reluctance to part with the Codex for fear it would be damaged or never be returned to them. “There should be restoration, for many of the pages are loose and frayed,” said keyholder Massouda. “But we prefer that the restoration be done in Egypt. Otherwise, perhaps, we will lose it.”

There is no evidence that the Codex was ever sent to England. In June 1981, two scholars from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem arrived in Cairo. They were Mordechai Glatzer, an expert on the history of Jewish paleography, and Malachi Beit-Arie, then the director of the Jewish National and University Library at the Hebrew University. Glatzer died last year, but Beit-Arie, now the Ludwig Jesselson Professor Emeritus of Codicology and Paleography at the university, says they studied the manuscript and brought along a photographer to make a new black-and-white microfilm version. They were very concerned about the deteriorating state of the Codex, and Beit-Arie recalls that his benefactor, Ludwig Jesselson, chairman of the board of both the Yeshiva University in New York and Bar-Ilan University in Israel, met with Egyptian officials and offered to finance its restoration, but nothing came of it.

A few months later, Sadat was assassinated, and the situation for the remaining Karaites—and the Codex—became more precarious. In 1983, Israel’s new ambassador to Egypt, Moshe Sasson, visited the Moussa al Dar’i synagogue at the invitation of Daniel Kurtzer, who had just stepped down as the American ambassador to Egypt, and his wife, Sheila. The two keyholders, Haroun and Massouda, as well as Menashe, were present. “The Karaites were very concerned about the welfare and safety of the Codex,” recalls Kurtzer. “Would somebody lay claim to it? Would someone try to seize it? It was a very complicated issue for a small community that was not mainstream and was always on guard and had to be very mindful of its status.”

Sometime in the mid-1980s, the guardians of the Cairo Codex and the other remaining Karaites left Egypt for Israel. Did they leave their beloved manuscript behind, or take it with them, as Menashe told Lurie they would? For 30 years, its whereabouts have been uncertain. “It is one of the great mysteries,” says Kurtzer.

Part II: Lost and Found

Just as the Cairo Codex vanished from view, scholarship about it heated up. For hundreds of years, there had been vigorous debate over the Codex. To Karaites, it and other Hebrew manuscripts were evidence of their role in preserving the holy text. Rabbinical Jews, on the other hand, often did everything they could to minimize the role of Karaites, even arguing that the Ashers were rabbinical Jews. Superimposed on this struggle were the typical disagreements of modern scholars. Many of the great names of 19th- and early 20th-century Western biblical scholarship pored over the Codex—via facsimiles and occasionally the real thing—and fought over questions such as: Could the Codex—and its first and most important colophon—really have been written by Moshe ben Asher in 894 CE? Were the minutiae of the markings that make up the text tradition that of Karaite or rabbinical Jewish scribes? Did the manuscript and the first colophon match?

It was into this fray in the 1980s that Mordechai Glatzer, Bar-Ilan University Judaic scholar Menachem Cohen, Malachi Beit-Arie and a few others leapt. Drawing on work by scholars who came before them and employing the tools of modern scholarship, they argued that the style of the markings and notes in the body of the Cairo Codex did not match that of other manuscripts written in the Asher tradition or even that of its own first colophon. They hypothesized that both the text and colophon had been copied from two different sources by a single scribe at a later date. “We doubted very much that the Codex was a Moshe ben Asher,” says Beit-Arie. “I thought it was a century later.” In hopes of laying doubts to rest once and for all, Beit-Arie decided to have the manuscript carbon-dated while he was on a sabbatical at Oxford University in 1984.

Beit-Arie had obtained a fragment of the Codex during his 1981 visit to the Moussa al Dar’i. While he and the other members of the Hebrew University team were photographing the Codex, a tiny scrap of plain parchment fell to the floor. “Because of its state—it was very dry—pieces were falling apart,” he says. “The people there wanted to get rid of all those pieces and I asked whether I could have one and they said, ‘By all means.’” He gave the small piece to an Oxford University lab to be tested, and the carbon-dating confirmed his suspicions: The very earliest that the Codex could have been written was 990 CE.

Lurie hopes to make new reproductions of the illuminated pages in order to publish them in a book.

“I don’t think somebody changed the Codex; it wasn’t tampered with, it was the original writing of someone who wanted to attach a lot of yichus,” says Beit-Arie, using the Yiddish word for pedigree. “It was a forgery but a genuine forgery.” Stefan Reif, professor emeritus of medieval Hebrew at University of Cambridge, explains it this way: It is as if, in order to preserve the manuscript, someone copied it in its entirety in the 11th century—updating the spelling and punctuation—and included the original colophon as well. “A parallel would be finding a letter written 100 years ago and recopying it in 2016: You copy everything but you correct it and modernize it,” Reif says. “But at the end of the letter is written: ‘This was written in 1916,’ and you copy these words out, too. So it is not really a document accurately dated to 1916, but rather to 2016.”

The Codex, in other words, is authentic, but scholarly consensus is that it was not actually written by Moshe ben Asher. Still, it remains deeply connected to Karaite identity and collective memory. The community today numbers 50,000 worldwide, with about 40,000 Karaites, mainly from Egypt, living in Israel—primarily in Ramle and Ashdod—and the rest in Turkey, Crimea, France, Switzerland and the United States, according to Neria Haroeh, a 32-year-old Israel-born Karaite of Egyptian descent. Haroeh is a lawyer who serves as chairman of the Supreme Council of Universal Karaite Judaism, the international body encompassing 12 jurisdictions and 14 synagogues. Like the sect’s religious body, the Council of Sages, it is headquartered in Ramle in a building called the Two Synagogues, which also houses a library, a religious court and offices.

“The Karaites care very much for the manuscript,” says Haroeh. Karaite religious scholar and hakham Yosef Aljamil, who has spent much of his life studying the Codex and other Karaite manuscripts, says, “It’s part of our lives, a glorious part of which we are proud.” Aljamil, 65 and born in Cairo, considers claims that the Ashers were not Karaites or that the Codex was not written by Moshe Ben Asher to be nonsense. “Who invented all these kinds of tests? All the rabbis have used this as their source. Who can deny this today?”

Karaite scholar-dealer Abraham Firkovitch.

A high-quality reproduction of an illuminated page from the Leningrad Codex.

American-born Karaite Shawn Lichaa, the 36-year-old director of the Karaite Jews of America and author of the Karaite blog “The Blue Thread,” says he was shaken when he first learned that Moshe ben Asher may not have written the Codex, but he has come to accept it. “When I was growing up, I always heard about how in the Karaite Synagogue in Cairo there was a beautiful manuscript and that they would take it out once in a while, usually on Yom Kippur, and everyone would line up to see it,” says Lichaa, who is also descended from Cairo Karaites. “They waited for a long time to catch a glimpse of it. People to this day think of it with great pride.” He adds: “The Karaite community should be proud of having maintained this ancient manuscript for centuries.”

In his writings, Mourad el Kodsi laments that most of the codices commissioned and written by Karaites are no longer in their possession, and many Karaites feel the same way. The list of lost manuscripts is long, and includes the Leningrad Codex, which contains the text of the entire Bible and has served as the basis for respected modern editions. It was written in 1008-1009 by Cairo Karaite scribe Samuel ben Jacob in the Asher tradition. Until Crimean Karaite scholar-dealer Abraham Firkovitch bought it and carried it off to Odessa in the 19th century, it was kept in the Rav Simcha synagogue. Along with more than 18,500 other items Firkovitch amassed—many of them from the Rav Simcha—it is now part of the collection of the National Library of Russia. A second ben Jacob codex disappeared from the Moussa al Dar’i in 1980. “These are only a few of the many Karaite codices that are now in the hands of non-Karaite libraries and museums,” el Kodsi writes.

In his writings, Mourad el Kodsi laments that most of the codices commissioned and written by Karaites are no longer in their possession, and many Karaites feel the same way. The list of lost manuscripts is long, and includes the Leningrad Codex, which contains the text of the entire Bible and has served as the basis for respected modern editions. It was written in 1008-1009 by Cairo Karaite scribe Samuel ben Jacob in the Asher tradition. Until Crimean Karaite scholar-dealer Abraham Firkovitch bought it and carried it off to Odessa in the 19th century, it was kept in the Rav Simcha synagogue. Along with more than 18,500 other items Firkovitch amassed—many of them from the Rav Simcha—it is now part of the collection of the National Library of Russia. A second ben Jacob codex disappeared from the Moussa al Dar’i in 1980. “These are only a few of the many Karaite codices that are now in the hands of non-Karaite libraries and museums,” el Kodsi writes.

But the most important codex that slipped away from the Karaites—and probably the best known—is the Aleppo Codex. “It’s the motherlode,” says biblical scholar Jordan Penkower of Bar-Ilan University. Written by Shlomo Ben Buya’tta and punctuated with vowel signs by Aaron ben Asher in 929 CE, its history was well documented by Matti Friedman in his 2012 book, The Aleppo Codex. Its story has interesting parallels to that of the Cairo Codex. The Aleppo Codex, which included the whole Bible, was presented to the Karaite community in Jerusalem in 930 CE and it, too, fell into the hands of the Crusaders. But it was redeemed for a vast sum by rabbinical Jews from a synagogue in Fustat, an ancient city near Giza that became part of Cairo and predated the Jewish and Karaite quarters. (El Kodsi says it was redeemed by a Karaite and given to a Karaite congregation in Fustat, which later converted to rabbinical Judaism.) Most scholars believe it was the unnamed manuscript read by the esteemed Jewish philosopher Maimonides, who declared it in his Mishneh Torah to be the most accurate version of Jewish holy text.

Somehow, in the 14th century, one of Maimonides’ descendants managed to extract the manuscript from the Fustat synagogue and take it to the Sephardic congregation in Aleppo, Syria. There, the “Crown of Aleppo” was zealously guarded for six centuries in a safe within a small crypt hewn in the rock beneath the great synagogue of Aleppo. Imbued with mythic qualities, it became the spiritual talisman for the entire community.

Some scholars in Palestine in the 1930s and early 1940s believed the Aleppo Codex belonged in Jerusalem, the spiritual center of the Jewish national renaissance, according to Friedman. Worried that the Syrian government might get its hands on the manuscript, the scholars made many attempts to convince the Aleppo community to part with it, even offering large sums of money. The Aleppo Jews refused all entreaties. In 1947, however, during riots following the United Nations vote on the partition of Palestine, the great synagogue was burned and the Aleppo Codex disappeared. It was hidden by a handful of Jews until 1958, when, with the help of Israel’s Mossad, it was smuggled out of Syria in a washing machine. In Israel, it was placed in the Ben-Zvi Institute, an academic body founded by Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a Hebrew manuscript scholar who was then Israel’s president.

The Aleppo Codex is on display today in The Israel Museum’s Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem.

The arrival of the Aleppo Codex in Israel brought about an exciting new era of biblical scholarship, but as it turned out, the manuscript was not safe: According to Friedman, 200 pages—around 40 percent of it, including the five books of Moses—went missing during the tenure of Institute director Meir Benayahu, a prominent scholar and manuscript collector who stepped down in 1970 and died in 2009. There was never a government investigation, and his family denies any wrongdoing.

The remaining sections of the Aleppo Codex have undergone extensive restoration, and today a few pages are exhibited along with the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest extant Hebrew scrolls, in The Israel Museum’s Shrine of the Book. Most of its pages are stored in a special climate-controlled room in the museum but beautiful color reproductions of the codex can be viewed online.

But what, in fact, happened to the Cairo Codex when its guardians left Egypt? Its whereabouts have been the subject of intense speculation in both the Karaite and scholarly communities for 30 years. There are two main theories. Theory number one is that the Karaites left it behind in Egypt, just as they left their synagogues, schools, public buildings, cemetery, homes and businesses. This is the theory promoted by the official Karaite community. “As far as I know it is still in the hands of the Karaite community, and it is still in Egypt,” says Haroeh, the Supreme Council chairman.

But what, in fact, happened to the Cairo Codex when its guardians left Egypt? Its whereabouts have been the subject of intense speculation in both the Karaite and scholarly communities for 30 years. There are two main theories. Theory number one is that the Karaites left it behind in Egypt, just as they left their synagogues, schools, public buildings, cemetery, homes and businesses. This is the theory promoted by the official Karaite community. “As far as I know it is still in the hands of the Karaite community, and it is still in Egypt,” says Haroeh, the Supreme Council chairman.

Lichaa says he does not know where the Codex is, but he has been told that it might have been moved to the Rav Simcha synagogue. “Another theory is that the Codex is still hidden somewhere in the Moussa al Dar’i synagogue,” he says. “But many people say that is impossible.” When the last Karaites left, they turned over the keys to their synagogues to the Jews who remained behind. The dozen or so elderly Jews who are still in Egypt are not in a position to do anything that the Egyptian government does not approve. The Egyptian Antiquities Ministry has jurisdiction over ten out of 12 synagogues in Egypt, including the Rav Simcha and the Moussa al Dar’i.

It is possible, says Lichaa, that the Codex could be elsewhere in Egypt. He has heard that it may be hidden in a bank vault in Cairo. “It could be under Egyptian government lock and key,” says Daniel Kurtzer, adding that none of the rumors he has heard over the years is credible. “It could be in someone’s home,” he adds. “It could be in Europe. It’s very unlikely, but it could be in Israel.”

Many of the people interviewed for this article stressed that the Codex was unlikely to be in Israel. Yet there are several Israel-related theories. One is that the Cairo Codex, like the Aleppo Codex, is one of the manuscripts allegedly stolen by the former director of the Ben-Zvi Institute. “According to this theory, the Codex was smuggled to Jerusalem, was briefly at the Institute and was then sold overseas—possibly to a collector on Long Island,” says Lawrence Schiffman, a prominent Dead Sea Scrolls scholar at Yeshiva University.

Lichaa brings up another theory. “By the way,” he asks, “are you writing this in connection with a guy named Zel Lurie? The theory I have heard from him is that it is in Israel. He is the only person who thinks this. It’s possible, but everyone else I’ve spoken to disagrees with him.”

As editor of Hadassah Magazine, Lurie traveled to Jerusalem frequently. About ten years after seeing the Cairo Codex, he visited the Karaite synagogue in the Old City, which had been rebuilt in 1982 by Egyptian Karaites in Israel. While at the synagogue, Lurie ran into Ferag Menashe, the Karaite shamash from Cairo. “He told me that the Codex had been safely smuggled out,” says Lurie, although he didn’t disclose any details.

As editor of Hadassah Magazine, Lurie traveled to Jerusalem frequently. About ten years after seeing the Cairo Codex, he visited the Karaite synagogue in the Old City, which had been rebuilt in 1982 by Egyptian Karaites in Israel. While at the synagogue, Lurie ran into Ferag Menashe, the Karaite shamash from Cairo. “He told me that the Codex had been safely smuggled out,” says Lurie, although he didn’t disclose any details.

Lurie didn’t think much about this exchange until 2012, when he visited his Israeli-born grandson in San Francisco. His grandson was dating the daughter of one of the thousands of Karaites who had immigrated to the Daly City, California area, and Lurie attended a Shabbat morning service at the only American Karaite synagogue, Congregation B’nai Israel. While there, he was handed a brochure that explained that the Cairo Codex had disappeared in 1984. “I hadn’t known that it was missing until then,” he says.

Lurie remembered the Codex’s beautiful carpet pages and made up his mind to have them professionally photographed and printed in a book. “I was searching for a way to celebrate my 100th birthday that would give the world something worthwhile after I was gone,” he says. First, he had to track the pages down. He made persistent inquiries to Karaites and decided he was not being told the truth. On May 2, 2012, he published a column in the Florida Jewish Journal called “The Double Mystery of the Cairo Codex,” in which he expressed his frustration that the Karaites, in his opinion, were hiding the Codex. That’s how he met a Karaite who shared his passion. David Marzouk lived in Boca Raton, and after reading Lurie’s column, he contacted him and came to visit. He brought with him a high-quality reproduction of one of the Cairo Codex’s carpet pages, even though the only images available to the public were from the 1970s and in black and white.

A poor-quality black-and-white microfilm facsimile of the Cairo Codex was produced in 1971. It did not include the illuminated pages. It is the only reproduction of the Cairo Codex that can be found online. A printed and bound version of it is on the shelves of the National Library of Israel.

Marzouk, who died in late 2014, was a retired Harvard-trained physician who came to the United States from Cairo in 1958 and, according to his son Ben, was a passionate scholar of Torah and Egyptian Karaite history. David Marzouk confirmed what Menashe had told Lurie when they met in Jerusalem: The Codex had been smuggled out of Cairo, along with two other manuscripts. “David told me that he believed that the original manuscripts were replaced with substitute manuscripts,” Lurie says.

Marzouk said that the Codex arrived in Israel in 1985, and that the Karaite community gave temporary custody of it to the Jewish National and University Library at the Hebrew University, which was then under the direction of Malachi Beit-Arie. Marzouk also said that the university gave the Karaites in Israel a letter certifying that they owned the manuscript. “I know nothing about the agreement, but everyone makes it clear that the Codex belongs to the Karaite community and they control its fate,” says Lurie. The Karaites, according to Marzouk, also received assurances that the location of the Codex would not be revealed.

Marzouk told Lurie he had first seen the Codex as a child at the Moussa al Dar’i on Yom Kippur, when it was placed on the bimah and the congregation filed past it. It was open to the carpet pages. “I shall never forget them,” he told Lurie. Marzouk, who helped underwrite el Kodsi’s book on modern Karaite history in Egypt, wrote Lurie that he wanted to rescue “these wonderful examples of medieval Jewish art from the secrecy in which the Israeli Karaites and Hebrew University have buried them.”

Marzouk was especially frustrated with the Jewish National and University Library. According to Marzouk, he and two other Karaites had been given permission from the Karaite authorities in Ramle in 2006 to digitize the Codex for the community. When they arrived at the library, he said, they were allowed to inspect the Codex, but were not permitted to photograph it. “David backed up his revelation with a photo taken surreptitiously in the locked room in 2006 in which he is pictured standing alongside the then-curator of Hebrew manuscripts,” says Lurie. Later efforts to digitize the Codex were also turned down by the library, which became an independent entity with a new name, the National Library of Israel, in 2007. Marzouk was concerned that the library was reneging on its agreement that the Codex would remain under Karaite control.

The following May, Lurie flew to Israel in pursuit of the Codex. There, the 100-year-old met with Haroeh, who told him the Codex was in Egypt and that David Marzouk was lying. Lurie also went to the National Library, located on Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus. He met with Aviad Stollman, who joined the library as its Judaica curator in 2010. As Lurie wrote in a June 2013 column in the Florida Jewish Journal, he came away with the firm belief that the Codex and the two other ancient Karaite manuscripts were in a climate-controlled room in a basement of the library. During an interview this fall in his library office, Stollman—who became head of collections in 2014—said the Codex was not at the library, although he was vague in his denial. “It could be anywhere,” he said. “It could be here. It could be in the Israel Museum. It could be in hands of private collectors. It could be in the Karaite shul in Jerusalem. It could be in the hands of the Karaites.”

Haggai Ben-Shammai, a professor emeritus of Arabic Languages and Literature at Hebrew University who retired as academic director of the National Library in September, is more forthcoming. He says that he has not seen the Codex but he has seen recent color scans of it. In fact, he says, a color edition was posted online by an American Karaite six or seven years ago, and it fell to Ben-Shammai to work with Karaite leader Haroeh to have it taken down. He also says that the Codex has “spent time” at the National Library since the Karaites did not have, at least initially, a facility with appropriate conditions. “I know that the Codex has been there,” he says. Sadly, he adds, the Codex has not been restored as far as he knows. “I can say with certainty that it has not undergone anything like the restoration of the Aleppo Codex.”

David Marzouk gave this page from his scrapbook to J. Zel Lurie in 2012.

Stollman and Beit-Arie, who in his eighties remains actively involved at the library, make it clear that they believe the Codex is better left unfound. They worry that the Egyptian government could lay claim to it, leading to a diplomatic crisis. “Everything now—including Torah scrolls and siddurs—is all considered part of Egyptian heritage,” says Andrew Baker, the American Jewish Committee director of International Jewish Affairs. A Jewish expatriate group, the Nebi Daniel Association, has not even been able to obtain community records that were kept in the synagogues, despite years of trying. Still, Baker says it is unlikely that the Egyptian government would pursue one of the many manuscripts that left the country in the 1980s in the aftermath of the peace agreement. Haggai Ben-Shammai believes that Egypt faces many other, far more critical challenges, making concerns about political repercussions less relevant than in the past. Lurie is more blunt. “I don’t think General el-Sisi is coming after the Codex,” he says.

There is a more pressing concern. Ownership of ancient manuscripts can be a thorny issue, and public awareness of the Codex could intensify tensions between the library and Israel’s Karaite community. The Ben-Zvi Institute’s control over the Aleppo Codex, for example, has been contested by the rabbis who helped smuggle it out. And the ownership of a dozen or so other valuable codices from Damascus that currently reside in the National Library is also in question. When the Mossad rescued Jews there about 20 years ago, the community wouldn’t leave without its manuscripts, which were only revealed to be in Israel in 2000. This sparked a struggle for control between the Damascus chief rabbi who helped smuggle them out and a group of Jewish immigrants from Damascus, who have agreed to let the codices remain at the National Library.

No one can know what kind of impact the reappearance of the Cairo Codex would have on the Karaites. It could exacerbate internal divisions or give rise to renewed interest in their heritage. For nearly a millennium, the Codex was part of the glue that held the Cairo Karaite community together. In an era of pluralism, intermarriage and assimilation, the maintenance of Karaite traditions in the face of the behemoth of rabbinical Judaism cannot be easy. It remains to be seen how the Karaites will traverse the next century, with or without the Codex.

Meanwhile, J. Zel Lurie, blessed with a long and healthy life, still hopes to publish a book with new color reproductions of the carpet pages. “They are not decorations that can be ignored,” he says. And at a time when scholars are fixated on making biblical manuscripts accessible, he believes it is a tragedy that a high-quality edition of the entire Codex is not available online. He wants the Codex to be shared with the world. “It is,” he says, “time to liberate the Cairo Codex from the shackles of fear that have kept it hidden.”

Marilyn Cooper, Marcy Epstein, Noah Phillips and Eetta Prince-Gibson provided research assistance for this story.

Images courtesy of Shawn Lichaa and Nadine Epstein