Visual Moment | Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich’s Bold Vision

“It was about changing culture throughout society…It was not just freeing for the body. It freed the spirit as well.”

Rudolph “Rudi” Gernreich was one of the most prominent fashion designers of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. His revolutionary designs and avant-garde collections embodied his vision of fashion as a liberating force that defied conventional ideas of beauty, identity and gender. “Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich,” on view through September 1 at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles, is the first exhibition to focus on the social and cultural impact of the influential designer’s body of work. The show features more than 80 ensembles, including his iconic topless swimsuit, microminis, thongs, unisex clothing and pantsuits for women—innovations that redefined style and brought him international renown. Also on display are original sketches, letters, photographs, historical footage of fashion shows and oral histories from friends and colleagues. The exhibition presents a comprehensive view of the designer’s life and work and illustrates how his bold designs continue to influence fashion today.

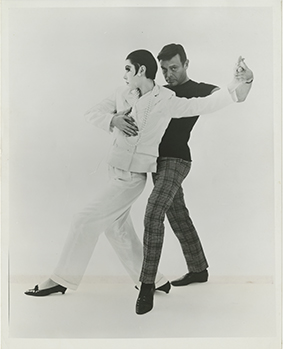

Gernreich dancing with model Peggy Moffitt (Photo credit: UCLA, William Claxton).

Born in 1922 to a wealthy Viennese Jewish family, Gernreich was eight when his father, Siegmund Gernreich, committed suicide. Remaining in Vienna with his mother, Elisabeth Muller Gernreich, the youth sketched and studied fabrics at his aunt Hedwig Muller’s dress shop. At age 12, he was invited by a prominent Austrian designer to apprentice in London, but his mother felt he was too young and declined the opportunity. When Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938, mother and son fled to the United States. They settled in Los Angeles, where 16-year-old Rudi, who spoke no English, began marketing his mother’s pastries door to door. His first actual job was in the morgue at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital, where he prepared bodies for autopsy. He later credited that experience with giving him an intimate understanding of the human body.

Gernreich’s personal history—as a Jew and a gay man—had a profound influence on his work. “After fleeing Nazi oppression as a teen,” says Skirball exhibition curator Bethany Montagano, “Gernreich encountered discrimination again. He would eventually find safe haven in the performing arts world and gay rights movement. These early experiences fueled his commitment to promoting a truer expression of self and designing clothes that proclaimed, ‘You are what you decide you want to be,’” as the designer himself put it.

Gernreich went on to study at both Los Angeles City College and the Art Center School, and in 1942 he joined the Lester Horton Dance Theater, which was known for its theatrical style. “Dancing made me aware of what clothes did to the rest of the body,” Gernreich said of his time with the Dance Theater. In 1950 he became a founding member of the Mattachine Society, a gay rights organization.

Gernreich working at his LA studio (photo credit: William Claxton).

Gernreich’s first jobs in the fashion industry were with Hollywood costume designer Edith Head and fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie of New York. He also collaborated on projects with companies such as I. Magnin Los Angeles. In 1952 he partnered with clothing manufacturer and fellow Viennese immigrant Walter Bass to produce designs that would help influence the look of California sportswear. Gernreich’s colorful, fresh, youthful outfits and dynamic graphics appealed to buyers and magazine editors alike and provided a welcome counterpoint to the staid influence of European couture. In the early 1950s, women came from all over the U.S. to see and buy Gernreich’s latest, most “far-out” designs at the Jax Boutique in Beverly Hills.

Gernreich’s designs for Caftan, 1970-1973.

Gernreich sought to create forward-thinking designs. He wanted to celebrate the body rather than suppress it. He had begun deconstructing swimsuits as early as 1952, creating knit swimwear that allowed women to swim unencumbered. Commissioned by Look magazine in 1964 and dubbed the “monokini,” his topless swimsuit exemplified his dedication to comfort and cemented his place in fashion history. Removing all interior structures, he allowed the body to assume its natural shape, challenging the 1950s ideal of rigid construction and a tightly cinched waist. His “No-bra” bra—wireless and formless—debuted in October 1964 and quickly became a bestseller. By 1965, an estimated three million “No-bras” had been sold nationwide, and their popularity soon spread abroad. Defying strongly held conservative ideas about a woman’s body, however, had its price. Critics in the Soviet Union claimed that the monokini signaled the end of morality in the United States. Some countries outlawed it. The Pope banned it, and at least two American women were arrested wearing it. Gernreich’s response: “I wanted to make a statement of freedom, not sexuality.”

Unity, functionality and comfort were key to Gernreich’s designs. He used sheer fabrics as well as leather and vinyl, and experimented with unconventional materials, incorporating large exposed zippers, plastic and metal springs and repurposing elements such as dog leashes as belts. His distinctive patterns and bright colors made his designs easily recognizable. He also ensured his clothing was reasonably priced, selling his fashions at mid-range retail chain Montgomery Ward. Contrary to high-fashion tradition, he preferred flat feet and had his models go barefoot or dressed them in low-heeled or flat shoes.

Gernreich’s work, however, was not only about clothes. He took on a number of social issues of the day, creating fashions that referenced student protests, growing racial tensions and the Vietnam War. “Fashion is not expected to be a social message. A designer is not expected to say something other than ‘Here is another dress,’” he explained. “But I would not be in this if that were the only thing required of me.”

As feminism expanded in the 1960s and ’70s, Gernreich offered women liberating fashion choices that overturned long-held expectations of how a woman should look and dress. His brash fashions thus became symbolic of women’s liberation. Forever testing boundaries, he designed his own unique take on the miniskirt, bringing the hemline up to 12 inches above the knee with his “micromini” and completing the look with tights, leggings and undershorts, helping to create a “mod” aesthetic. His tailored pantsuits introduced the idea of androgyny into conventional fashion, and his revolutionary thong underwear quickly became a staple of contemporary dress, paving the way for the designs of today.

Gernreich often expressed frustration with the fashion industry. “It’s a much more positive act to face today,” he maintained, “than to try to escape it by hiding in the past.” With the introduction of his Unisex Collection in 1970, the designer brought his vision of the future to life. Stripping away gender markers, he created garments that could be worn interchangeably by anyone. His jumpsuits and caftans abstracted the body and posed questions about gender fluidity. “I see Unisex as a total statement about the equality of men and women,” he declared in 1970. “Their different sexual natures no longer need the social support of differences of dress. Unisex reveals nature…It doesn’t hide or confuse it.”

The Fearless Fashion exhibit honoring Gernreich at the Skirball Center (photo credit: Larry Sandez).

Although he closed his company in 1968, Gernreich continued to design womenswear. He also found time for social advocacy, supporting the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment, contesting the stigma of mental illness and working for the election of the first African American mayor of Los Angeles, Tom Bradley. He sought new creative projects as well, experimenting in housewares, fragrances and gourmet soups. In early 1985, he was diagnosed with lung cancer and passed away a few months later at age 62.

“At the Skirball, where we are guided by the Jewish tradition of welcoming the stranger,” says curator Montagano, “we are inspired by how Gernreich did just that: his apparel welcomed everyone into the fold—regardless of race, religion, gender, sexuality, and body type—broadening the scope of who is ‘fashionable.’ It is a message that resonates to this day.”