An Inconvenient Genocide

Why we don't know more about the Uyghurs

To read and/or print this story in PDF format, click here.

To read more Daniel Pearl Investigative Journalism reports, click here.

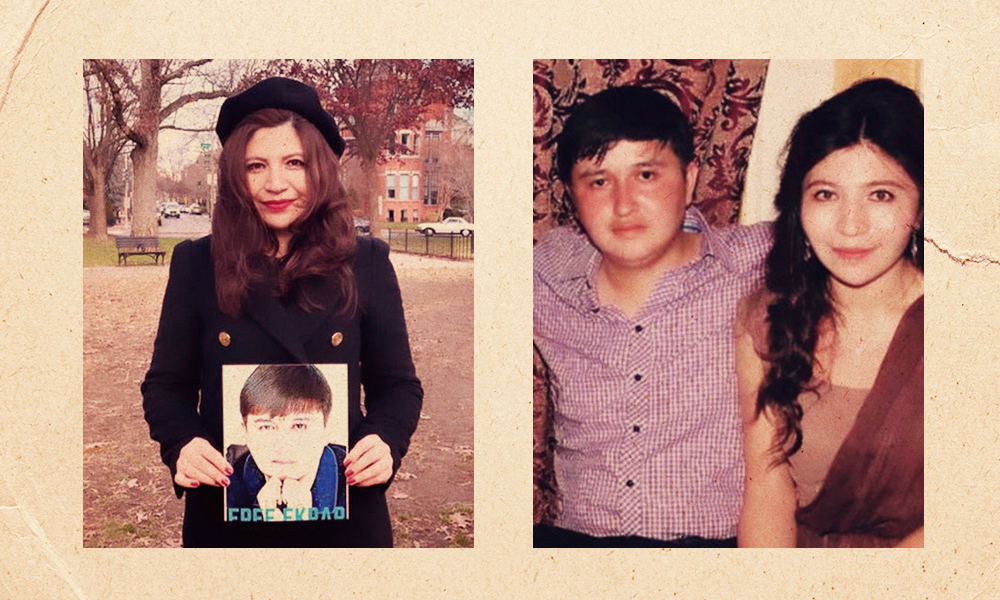

WHEN RAYHAN ASAT met her younger brother Ekpar for dinner in Washington, DC one February night in 2016, they each had reason to celebrate. In three months, Rayhan would graduate from Harvard Law School with a master’s degree, the first Uyghur to do so and thus a source of Asat family pride. But Rayhan was just as delighted by her brother’s success. A tech entrepreneur and social media star in their hometown of Urumqi in northwest China, Ekpar had been invited to Washington by the U.S. State Department under its prestigious International Visitor Leadership Program.

As they strolled down M Street after dinner at Clyde’s, a popular Georgetown restaurant, Ekpar told his sister about the people and places he was encountering as part of his three-week program and how it was giving him confidence about China’s own future. “Look at me,” Rayhan recalls him saying. “I am in Washington, representing China as a Uyghur. China wants us to be innovative and creative.” Before he flew back to China, they met again over pizza in Manhattan. Ekpar told his sister he and their parents would come to Cambridge in May to attend her law school graduation.

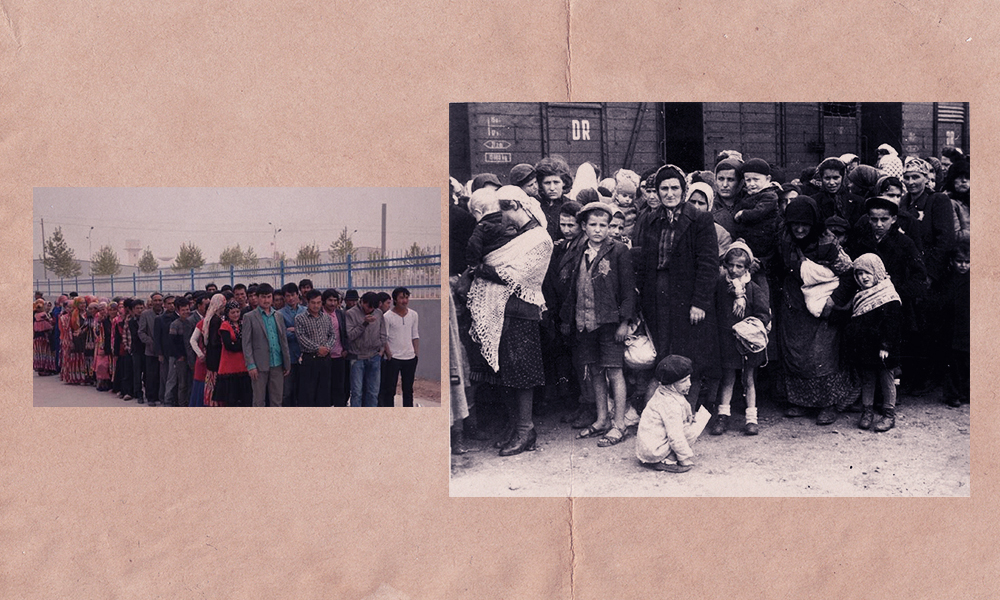

The family reunion did not happen. Three weeks after returning from the United States, Ekpar was suddenly taken away by Chinese Communist authorities. No explanation was given, but Ekpar’s detention fits a pattern that would soon become familiar among the Uyghurs, a mostly Muslim ethnic minority concentrated in the Xinjiang region along China’s western border. In the four years following Ekpar’s detention, up to a million Uyghurs considered a potential threat to Communist authority would be sent off to camps for “re-education.” Party authorities sometimes claimed the detainees had shown indications of religious extremism or support for terrorism, but the Asat family was secular; moreover, the detentions of recent years have been part of a broad and violent crackdown on the Uyghur people.

What the U.S. State Department had found most impressive about Ekpar Asat was what the Chinese government apparently saw as most incriminating: He had demonstrated a potential to inspire other young Uyghurs. At a time when the Communist Party was focused on consolidating power and enforcing its ideology, Rayhan says, it did not want young Uyghurs thinking for themselves. “Ekpar was taken because he showed leadership,” she tells me, “especially among those people who are eager to learn and explore the world and shape a different kind of society.” He had earned accolades for his work with older Uyghurs and children with disabilities and founded a social media app that featured news about Uyghur history, literature, entertainment and music.

“That’s what got him in trouble,” says James Millward, a Georgetown University historian who writes on Uyghur affairs. “He was a golden boy. And there are many others like him. The [Uyghur] elites have been targeted. The most cosmopolitan people are definitely in the crosshairs.”

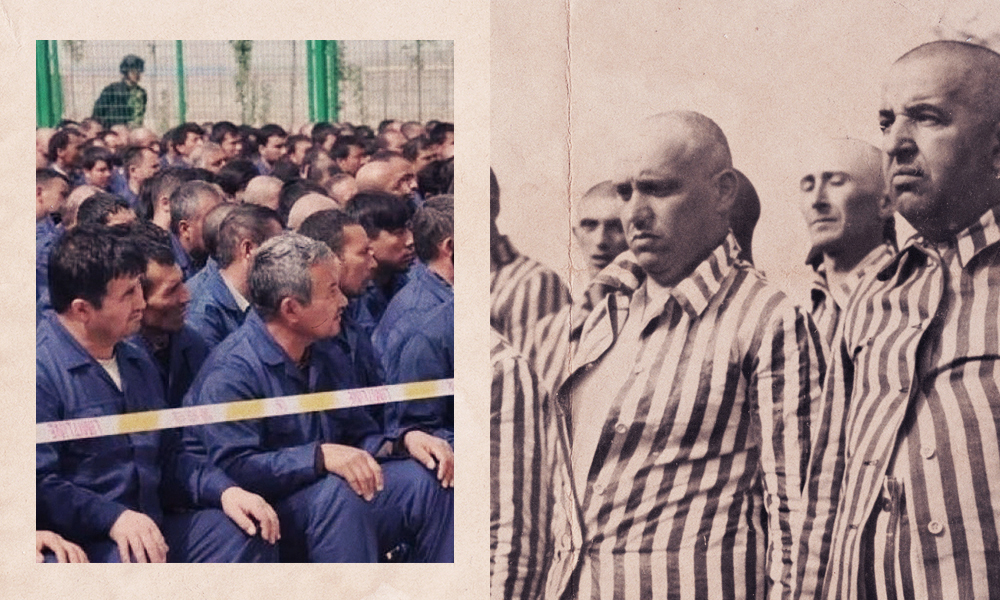

The Xinjiang region, home to about 11 million Uyghurs, is mostly off-limits to human rights investigators, but abundant evidence suggests that the Chinese authorities are determined to assimilate the Uyghur minority into the ethnic Han Chinese majority by force, eliminating them as a separate population and erasing their identity. According to numerous reports, the Uyghurs’ leaders have been imprisoned, their culture, religion and language suppressed, their families broken apart, and Uyghur women subjected to involuntary sterilization. Since 2017, the Communist Party’s treatment of the Uyghur population has grown into one of the most serious cases of human rights abuse in the world, arguably one of genocidal proportions.

Rayhan Asat has heard nothing from her brother since his 2016 detention. In December 2019, a bipartisan group of U.S. senators wrote to the Chinese Embassy in Washington to demand information about Ekpar’s fate. A month later, they were told he had been convicted of “inciting ethnic hatred and ethnic discrimination” and sentenced to 15 years in prison. He is believed to be held in solitary confinement at a prison in Aksu Prefecture, on the western edge of the Xinjiang region. Since learning of his conviction, Rayhan has been working tirelessly for his release, but to no avail.

Like other Uyghur exiles, she fears that China, with the world’s second largest economy, is simply too important to be held accountable for its actions. Products made in China are key elements in manufacturing supply chains around the world. Multinational corporations find the enormous Chinese consumer market irresistible. The U.S. and European governments need China’s cooperation to deal with trade issues, climate change and rogue states such as North Korea. American universities have come to depend on tuition revenue from Chinese students. Countries in need of investment and foreign aid look to China for help, even if it means ignoring repression. Uyghur exiles in the United States and elsewhere lament that the suffering of their people, including friends and family members, has gone largely unrecognized as a result.

“If the leading democracies are all beholden to the Chinese government, what am I going to do? have no power. I’m nobody. I’m just one individual against a very powerful Chinese government.”

“If the leading democracies are all beholden to the Chinese government, what am I going to do?” says Rayhan, one of about 5,000 Uyghur exiles in the U.S. “I have no power. I’m nobody. I’m just one individual against a very powerful Chinese government.”

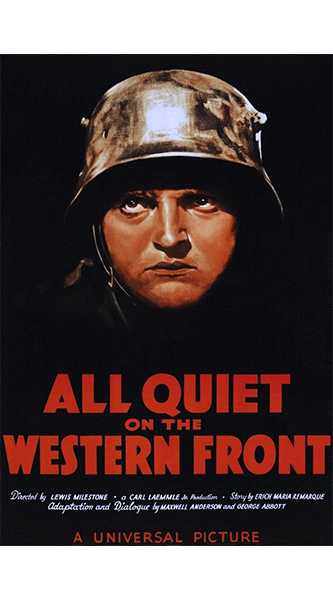

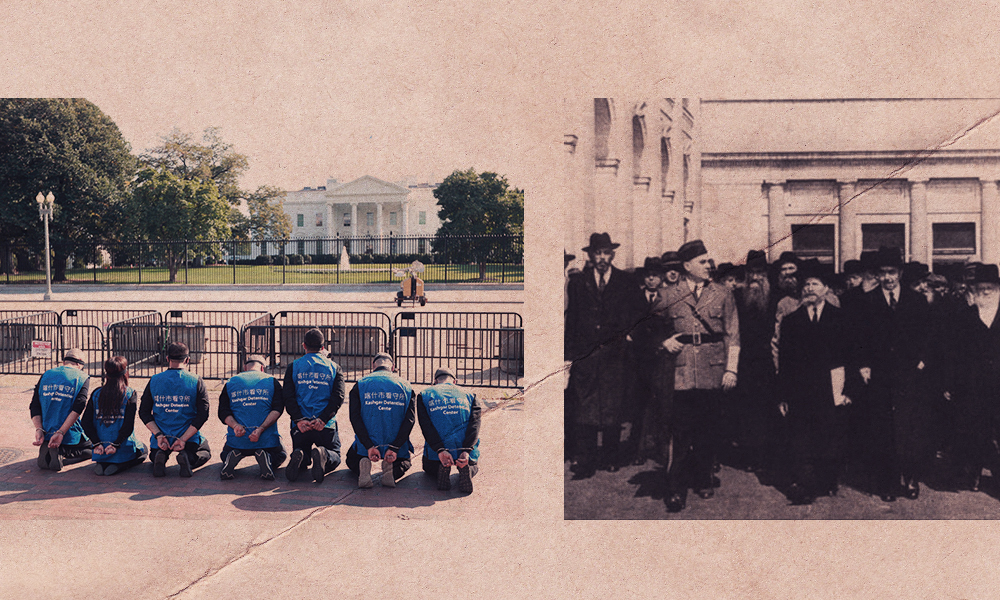

Human rights advocates see a parallel between the muted response to China’s repression of the Uyghurs and America’s failure to challenge Nazi moves against the Jews in the 1930s, a time when the United States had deep political and economic interests in Germany. Senior American officials, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, hoped a conciliatory approach to Hitler would encourage Germany to continue payments on its multibillion-dollar debt to U.S. creditors. Wall Street bankers were heavily invested in German industry and wanted to protect their stakes. Major Hollywood studios were omitting movie references to Jewish mistreatment in order to satisfy Nazi censors and maintain access to the important German film audience.

One lesson of those years was that it was a moral failure to let competing interests impede an effective response to the Nazi horror. The plight of the Uyghur people in China presents an opportunity to see whether that lesson was learned.

THE NAZIS’ DRIVE to eliminate Europe’s Jewish population was so thorough and horrifying that it inspired the creation of a new word, “genocide,” from the Greek word for race, genos, and the Latin suffix caedo or cide, meaning killing. The man who coined the term, Raphael Lemkin, was a Jewish lawyer who worked as a prosecutor in his native Poland, with a private interest in international criminal law and state-sanctioned atrocities. Many of his family members were killed in the Holocaust, but Lemkin managed to make his way to Sweden and then to the United States, where he wrote his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe.

The Nazi plan for Jews was straightforward: Kill them all. In the case of the Uyghurs, few suggest they have been victims of massacres. Lemkin, however, saw genocide as a multidimensional enterprise, one that did not necessarily require mass murder. He defined it instead as “a coordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves.” Lemkin’s definition became the basis for the United Nations’ adoption of the Genocide Convention in 1948, and it is relevant to the Uyghur situation. In March 2021, a group of 32 prominent legal scholars, human rights experts, parliamentarians and historians endorsed a report by the Newlines Institute and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights: It concluded that the systematic efforts by Chinese Communist authorities to destroy the Uyghur identity and diminish their separate existence in China met the legal definition of a genocidal campaign.

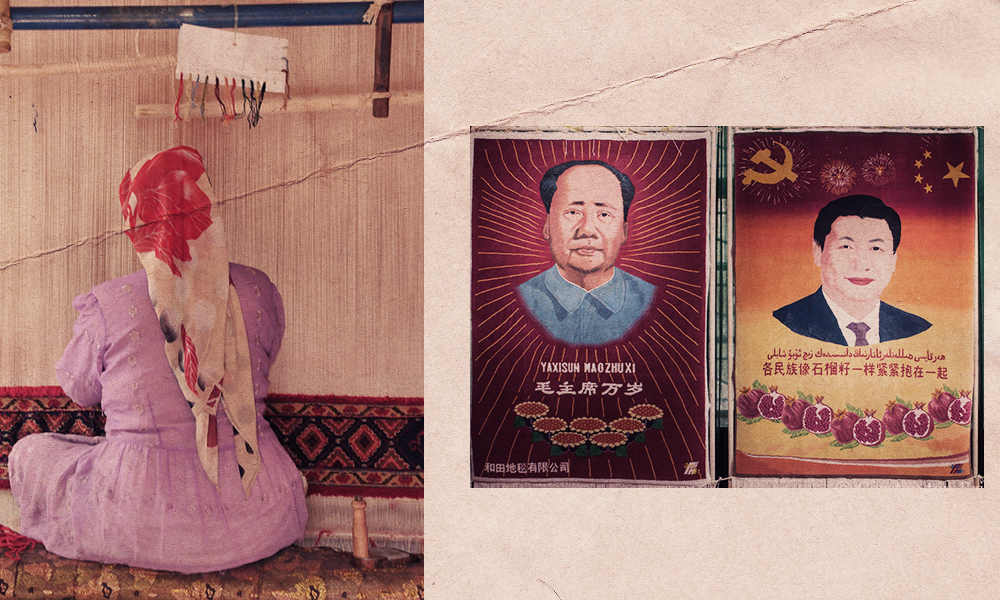

The Uyghurs have roots dating back at least 1,500 years. Speaking a Turkic language, they are closer culturally to the people of Central Asia than to the majority Han population in China. Anthropologist Sean Roberts of George Washington University, who specializes in Uyghur history, says their conversion to Islam came gradually between the 10th and 13th centuries, under Arab influence. The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, the official name for the Uyghur homeland, has long been seen by Chinese authorities as strategically important, with rich oil and gas reserves and about 85 percent of the country’s total cotton production. After the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, Party officials sought to tie the Xinjiang region more closely to the unified Chinese Communist state.

Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the 1980s brought a somewhat more accommodating approach. In his 2020 book The War on the Uyghurs, Roberts says he saw evidence of a “cultural renaissance” on his first visit to the Uyghurs’ region in January 1990, with rekindled interest in Islam and growing use of the Arabic script. The breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, however, raised concerns in China about a similar fragmentation along ethnic lines in China. “That really created significant anxiety on the part of the Communist Party,” says Roberts. “They developed an obsession with secession.”

As such former Soviet republics as Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan gained their independence, China initiated an aggressive drive to combat “splittism” in Xinjiang, a term that Roberts says authorities use to characterize any move to “split the motherland.” There is, in fact, a small Uyghur independence movement, but prominent exiles insist it does not represent a majority view. Of what they call the “three evils” of separatism, religious extremism and terrorism, the government is especially focused on religious practice, waging an intense anti-Islam drive in Xinjiang. Mosques have been closed or destroyed, and public calls to prayer are prohibited. People who greet each other with the Arabic phrase “Assalamu Alaikum,” or “Peace be upon you,” became targets. China has also introduced the most intrusive surveillance system the world has ever known in Xinjiang. Party officials collected DNA samples, iris scans and voice samples to construct a database of the Uyghur population. Video footage gathered through the surveillance system has allowed the government to identify those Uyghurs who wear traditional dress, women who are veiled and men with “irregular” beards.

More broadly, the surveillance system enables the government to identify any Uyghurs whose behavior or appearance suggests that they are straying from acceptable practice or Communist orthodoxy. Uyghurs with smart phones have found spyware installed on their devices, allowing the authorities to monitor their movements and communications. “Work teams” consisting of Han Chinese loyal to the Communist Party have been assigned to move in with Uyghur families, often for several days at a time, in order to document family habits, private conversations and religious practice. In some cases, Uyghurs are even expected to share their beds or sleeping platforms with these uninvited visitors.

Those Uyghurs whom officials see as unlikely to assimilate may then be sent for “re-education” at detention camps. An investigation by Human Rights Watch in 2018, based on interviews with Uyghurs who had fled Xinjiang, suggested that “red flags” for detention included traveling abroad or having contact with someone who did, speaking one’s native language in school, or abstaining from alcohol or tobacco. One Communist Party propaganda message obtained by Radio Free Asia’s Uyghur service explained that those Uyghurs “chosen” for “re-education” are actually ill, “infected with religious extremism and violent terrorist ideology, and therefore must seek treatment from a hospital as an inpatient.”

China has not released an accurate tally of the Uyghurs detained in these camps, nor allowed an independent investigation, but surveys in the Xinjiang region suggest that at least 10 percent of the population are currently detained, meaning about a million Uyghurs. The 2018 Human Rights Watch investigation and other inquiries by human rights groups concluded that Uyghur detainees have been subjected to forced political indoctrination, torture, beatings, food deprivation and prohibited from speaking in their native language.

Some who made their way out of the camps said they had been told the only way to win release was to demonstrate loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party. Some were freed only on the condition that they work in Xinjiang cotton fields under virtual slave conditions or in factories where they are supervised by Han Chinese foremen. Others, like Ekpar Asat, have been taken from the detention camps only to be sentenced to long prison terms on vague charges, with minimal due process.

Such prosecutions became much more frequent beginning in 2017, when a total of 227,882 criminal arrests were recorded in the Xinjiang region, compared to just 27,404 a year before, according to data compiled by Georgetown University’s Millward. The increased repression of the Uyghurs that year coincided with a major turn toward increased authoritarianism on the part of Chinese President Xi Jinping.

“Xi was trying to crack down on any kind of dissent,” says Sean Roberts. In a speech before Xinjiang Communist officials in September 2020, Xi praised their work as “completely correct,” saying a “Chinese consciousness” should be the basis for ethnic unity. “We must adhere to the Sinicization of Islam in Xinjiang” and carry out “the project of cultural invigoration,” Xi said. Uyghur culture itself had come to be seen as a political threat to a Chinese Communist project that requires conformity and obedience.

In a paper written for the Brookings Institution, Millward observed that repressive policies by the Chinese government in the Xinjiang region “go far beyond constraints on religion, to target the Uyghur language itself and arbitrarily incarcerate intellectual elites and Uyghur [Communist] party members who are patently secular.”

One of the earliest examples of the crackdown on Uyghur intellectuals was the December 2013 detention of Ilham Tohti, an economics professor at Central Nationalities University in Beijing. Tohti did not support Uyghur independence and was respected among Han Chinese intellectuals. In The War on the Uyghurs, Roberts wrote that Tohti advocated “a Xinjiang where Uyghurs had more control over their destiny and were respected as equals with the Han,” a position the authorities apparently found unacceptable. At the time of his detention, Tohti was on his way to accept a visiting professorship at Indiana University. He had asked his teenage daughter, Jewher Ilham, to accompany him. Tohti was stopped just before boarding his international flight. When it became clear he would not be allowed to leave, he insisted that his daughter go on without him.

“At least one person in our family should be free,” Jewher recalls her father telling her. In September 2014, Tohti was convicted of “separatism” and sentenced to life in prison. His daughter, now living in Washington, DC, has not heard from him since.

The determined effort by Communist authorities to erase the Uyghur identity and suppress any independent Uyghur thought is just one indicator of possible genocidal intent. Other actions prohibited under the U.N.’s Genocide Convention are the imposition of “measures intended to prevent births within the group” and “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” Children of imprisoned Uyghurs have been sent involuntarily to boarding schools where they are forced to learn and speak Mandarin, the language of the Han Chinese majority. In addition, government reports and surveys of Uyghur women in exile in Turkey indicate that the Chinese Communist authorities have instituted a policy of forced sterilization and involuntary fitting of IUD devices. While data are scant, birth numbers tell a revealing story. Research by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute showed that the birthrate in areas where Uyghurs dominate fell by about half between 2017 and 2019. That drop was greater than what has been reported in any global region during more than 70 years of fertility data collection by the United Nations and suggests that the Chinese government wants to gradually eliminate the Uyghur population.

Some Chinese leaders have as much as admitted that genocide is their policy. In 2017, a religious affairs official in the Xinjiang region, Maisumujiang Maimuer, writing on the state-sponsored Xinhua Weibo website, said the goal with respect to the Uyghurs was to “break their lineage, break their roots, break their connections and break their origins.”

UPON HIS ARRIVAL in Germany in July 1933, U.S. Ambassador William E. Dodd was informed of the growing persecution of Jews by his top consular officer, George Messersmith. Historian Erik Larson lays out the story in his 2011 book In the Garden of the Beasts. Dodd learned that Hitler had ordered that all “non-Aryan” people (anyone with one or more Jewish grandparents) be barred from government jobs. Hitler’s brown-shirted stormtroopers were parading noisily in the streets of Berlin and other German cities.

An issue of Time magazine released that same month featured Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels on the cover. An article inside described how Hitler and Goebbels had managed to lift the spirits of the German people in the aftermath of the country’s humiliation in World War I by scapegoating the Jews. The magazine reported that Jewish bankers were being regularly denounced as scheming speculators and that Hitler was openly threatening to order the sterilization of its Jewish population.

Such reports alarmed American Jews. Rabbi Stephen Wise, honorary president of the American Jewish Congress, repeatedly urged President Roosevelt to denounce the anti-Jewish moves and personally called Ambassador Dodd’s attention to what German Jews were experiencing. Dodd had heard a different message, however, in the weeks preceding his move to Berlin. In New York, he had met with bank executives, many of whom were deeply involved in managing German investments. Dodd found they were most troubled by the millions of dollars they were holding in German bonds.

President Roosevelt had similar concerns. In a meeting with Dodd before he left to take up his diplomatic post, Roosevelt suggested the ambassador not focus too closely on the situation with German Jews. “The German authorities are treating the Jews shamefully and the Jews in this country are greatly excited,” Roosevelt said, according to Larson. “But this is also not a governmental affair. We can do nothing except for American citizens who happen to be made victims.”

At the time, an inclination to appease the Nazis was evident throughout the ranks of American industry, from Detroit to Atlanta and even Hollywood. Standard Oil, General Motors, Ford, IBM and Coca Cola all had factories in Germany during Hitler’s early years in power. General Motors and Ford in particular were deeply involved in the German economy through their subsidiaries, Opel and Ford Germany. By 1939 they controlled about 70 percent of the German car market, and their production had contributed mightily to Hitler’s rearmament program. The two companies were the largest producers of trucks for the German army and accounted for half of Germany’s production of tanks.

Some GM and Ford executives, in fact, were enthusiastic collaborators with the Nazi regime. James Mooney, the head of GM’s European business, met personally with Hitler as early as 1934. A month later, his company publication, General Motors World, told the story of the Hitler-Mooney meeting, describing the Führer as “a strong man, well fitted to lead the German people out of their former economic distress…by intelligent planning and execution of fundamentally sound principles of government.” Henry Ford, already notorious for his antisemitism, was likewise enamored of Nazi Germany under Hitler.

The auto executives by then were thoroughly aware of what was happening to German Jews, but profits were clearly more important. Washington Post reporter Michael Dobbs in 1998 uncovered a letter GM chairman Alfred P. Sloan wrote to a shareholder defending his company’s operations in Nazi Germany on the grounds that they were “highly profitable.” Germany’s internal affairs, Sloan argued, “should not be considered the business of the management of General Motors.”

No German firm was more closely linked to the Nazi war effort than I.G. Farben, a giant chemical syndicate that dominated the manufacture of products essential for the war economy. In its early days, I.G. Farben had some Jews on its board of directors, but under Hitler the company replaced them all with hardcore Nazis. It was I.G. Farben that ultimately invented, produced and distributed Zyklon B gas for use in the Nazi gas chambers, and the company actually operated a chemical factory at the Auschwitz concentration camp.

What is less well known is that the company’s dramatic growth was made possible in significant part by American technical assistance and bank financing. The company even had a U.S. subsidiary, American IG, with Henry Ford’s son Edsel and Walter Teagle, the president of Standard Oil of New Jersey, among its directors. One of the company’s key U.S. advisers was John Foster Dulles, at the time a senior partner at the powerful Sullivan & Cromwell law firm in New York (and subsequently Secretary of State in the Eisenhower Administration). In the early 1930s, Dulles specialized in representing U.S. commercial interests in Germany and Nazi business interests in the United States. He continued to work with I.G. Farben even after the company purged all its Jewish associates and embraced Hitler’s vicious antisemitism.

The extensive business ties that American industrialists and Wall Street bankers had with Nazi interests hindered efforts by the U.S. government to craft a response to Hitler’s growing power.

The extensive business ties that American industrialists and Wall Street bankers had with Nazi interests hindered efforts by the U.S. government to craft a response to Hitler’s growing power. Ambassador Dodd expressed his frustrations in a 1936 letter to President Roosevelt, reported in Antony C. Sutton’s 1976 book Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler.

“[T]he breakdown of democracy in all Europe will be a disaster to the people. But what can you do?” Dodd wrote. “At the present moment, more than a hundred American corporations have subsidiaries here or cooperative understandings…I mention these facts because they complicate things and add to our war dangers.”

THE UNITED STATES TODAY is far more deeply interconnected with China than it was with Germany in the 1930s, and any effort to challenge China over its treatment of the Uyghurs is even more complicated than what Ambassador Dodd and President Roosevelt faced with Nazi Germany in those pre-war years.

Since the U.S. established full diplomatic relations with China in 1979, China has grown to become the largest U.S. trading partner, the top source of U.S. imports and the third-largest U.S. export market. During this period, China has embraced pro-growth policies through a system of state-sponsored capitalism and has engaged fully in the global economy. These actions have lifted hundreds of millions of Chinese out of poverty. Chinese aid and investment have fueled the growth of countries throughout the world. American consumers have come to depend mightily on products made in China, and economic disengagement from the country is now virtually inconceivable. The country has not moved significantly toward democracy, but that has not become a major barrier in the relationship. America’s trade with China and bilateral cooperation on other issues have meant the U.S. has, on occasion, turned a blind eye to China’s authoritarian policies toward the Uyghurs.

Until recently, few Americans knew anything about the Uyghur people, much less about their repression. The Uyghurs first captured the attention of U.S. policymakers in the aftermath of the 9-11 attacks, and it was in a negative light. President George W. Bush and other global leaders were turning their attention to terrorism, particularly Islamist radicalism. The global counterterrorism efforts offered China a convenient justification to crack down on Muslim Uyghurs and insulated it from criticism from the United States for doing so. In 2003, the Bush Administration agreed to a Chinese request to designate a little-known Uyghur group, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement, as a terrorist organization. Human Rights Watch (HRW) noted that the evidence for the U.S. designation appeared to come straight from the Chinese government. HRW concluded that the move mainly showed the Bush Administration was “keen after September 11 to enlist Chinese support in its efforts against Islamist terrorism.” In 2002, the U.S. military detained 22 Uyghurs at Guantanamo Bay on suspicion of links to Al-Qaeda, thus reinforcing Chinese claims about Uyghur militancy.

No evidence of such ties emerged, however, and in 2008 a U.S. federal judge ordered all the Uyghur detainees released. Concerns about possible Uyghur ties to terrorism have diminished considerably since then. Some Uyghurs, radicalized by their experience of Chinese repression, have indeed gone to Syria to join ISIS or been lured there by ISIS propagandists. Sean Roberts and others who have studied that movement, however, say the allegations of terrorist or extremist inclinations among the Uyghurs have been consistently overstated. “I do not really see them as a terrorist threat,” Roberts says.

During Barack Obama’s presidency, the United States marginally increased criticism of China’s treatment of the Uyghurs, though advocates for their cause were disappointed that more assertive actions were not taken. Like previous presidents, Obama generally focused his China policy on trade, intellectual property rights, security issues around the South China Sea and the status of Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The sharply increased repression of the Uyghurs after 2017, however, made China’s policies too obvious to ignore. The Trump Administration generally preferred to speak about human rights in the context of concerns about international religious freedom issues, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo used one such occasion in September 2018 to denounce the “awful abuses” suffered by the Uyghurs being held in detention camps. At the time, senior officials at the State Department and the White House were preparing sanctions to be imposed on Chinese officials involved in the Uyghur repression. They encountered resistance, however, from the Treasury Department. According to a New York Times report, the administration decided to shelve the sanctions after President Trump met with President Xi Jinping during a G20 meeting in Argentina that December. President Trump later told Jonathan Swan of Axios that he decided to hold off on the sanctions because “we were in the middle of a major trade deal.”

In the months that followed, some in the administration nevertheless continued to advocate for pressure on China over its treatment of the Uyghurs. Keith Krach, Trump’s undersecretary of state for economic growth, energy and the environment, focused on three Chinese tech giants–Alibaba, Tencent and Baidu–that he saw as enablers of the surveillance operations in Xinjiang. Krach, a former CEO of DocuSign and other major tech firms, asked the Department of Labor to issue a business advisory to U.S. pension-fund managers suggesting that they review their investments in the three tech companies.

“That would have been appropriate,” says Krach. “But I couldn’t get it to move.” Between the Treasury Department’s resistance to sanctions and the Labor Department’s hesitancy on a business advisory, Krach acknowledges that he was frustrated that more was not done for the Uyghur cause during the time he was in government. “But we moved the needle in a lot of ways,” he says, referring to the increase in public awareness of Uyghur repression. “I’m happy to see that this has become a nonpartisan issue.”

The inclination to do something about the repression of the Uyghurs was evident on Capitol Hill, and it was indeed bipartisan. Republicans and Democrats on the House Foreign Affairs Committee wrote jointly to Pompeo in August 2018 asking that “strong measures” be taken in response to the Chinese Communist Party’s abuse of Uyghur human rights. In an unusual coalition, conservatives and human rights groups alike supported the move. After the administration declined to impose sanctions against the responsible Chinese officials, in March 2019 the committee members wrote back “with a renewed sense of urgency.” This time, the members added a request that the administration investigate whether U.S. companies were providing technology to China that could be employed in the surveillance of the Uyghur population.

Legislators from both parties had meanwhile introduced bills in the House and Senate that would compel the administration to scrutinize U.S. business transactions related to Xinjiang. One such bill, the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act, required U.S. government agencies to report on human rights abuses committed against the Uyghurs and mandated sanctions on the Chinese officials found responsible. One version passed by unanimous consent in the Senate; another passed the House by a vote of 407-1, and the legislation was signed into law by President Trump.

At the time, John Bolton, Trump’s former national security advisor, had just released a memoir in which he said a U.S. interpreter who was present during a private conversation between Trump and Xi in June 2019 had told him that Trump gave Xi a green light to continue building detention camps for the Uyghur Muslims and said that it was “exactly the right thing to do.” Trump denied making the statement, but he signed the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act without endorsing it publicly or mentioning the human rights abuses that had prompted its passage.

Without a White House comment during a busy news cycle, the enactment of the legislation got little attention, and it has had only a marginal effect. A month later the Treasury and State Departments announced largely symbolic sanctions against four Chinese officials, including Chen Quanguo, the top Communist Party official in Xinjiang. The legislation also required the U.S. government to submit a report to Congress within 180 days on any continued human rights abuses in Xinjiang, but that deadline coincided with the end of Trump’s term in office, and the report was never submitted.

On January 19, 2021, one day before leaving office, Secretary Pompeo announced that the U.S. government had concluded that China’s treatment of the Uyghur population qualified as genocide. Again, Trump made no comment on the announcement. Pompeo’s successor, Antony Blinken, almost immediately said he agreed with the assessment, and two months later, the Biden Administration officially reaffirmed the genocide declaration. Its practical significance remained limited, however. State Department lawyers have generally held that while a genocide declaration suggests a moral responsibility to take preventive action, it is not a legal responsibility.

HOLLYWOOD’S MORAL FAILURES

Are studios appeasing China the way they appeased the Nazis?

In the 1930s, when Wall Street bankers and U.S. corporate executives were putting their business interests ahead of any concern for German Jews, a similar story was playing out in Hollywood. Germany was one of the world’s largest movie markets, and the big studios were fearful that Hitler might bar American movies from being shown there. In his 2013 book The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler, Ben Urwand revealed how major studios agreed to censor scripts and make other adjustments to satisfy the German government. The German consul in Los Angeles warned that if any Hollywood studio produced a movie to which the Nazis objected, all films by that studio would be barred in Germany. Moreover, the studios agreed that the same cuts made in films to be shown in Germany would be made in all versions shown anywhere.

“The studios gradually managed to obtain an understanding of the Nazis’ new censorship methods,” Urwand wrote. “They figured out which Hollywood actors the Nazis considered undesirable, and they made sure not to submit any films in which these actors played a role. They also found that they could still submit pictures employing Jews as long as they made appropriate adjustments to the credits.” The appeasement measures worked for a time. The studios in 1938 sold almost as many movies in Germany as they had before Hitler came to power.

Hollywood these days is not as cowed by China as it was by Nazi Germany. Chinese sensitivities nevertheless have to be considered, if only because of the massive size of the Chinese market. When a sequel to War Games, a 1983 Cold War thriller, was conceived in 2006, the producers gave the writers a warning, according to one of those involved: “China can’t be the bad guy.” A 2012 remake of the movie Red Dawn was originally a story of American teenagers fighting off an invasion by China. By the time it was released, the invasion came from North Korea. In a parallel to the Nazis’ demands, contracts may stipulate that whatever version is approved for China has to be the version distributed worldwide.

It’s not just what is in the film that can incur the wrath of Chinese authorities. In May 2021, John Cena, the professional wrestler and star of the film Fast and Furious 9, inadvertently got into trouble by referring to Taiwan as a “country” in an interview. The reaction on Chinese social media was immediate and angry. The Fast and Furious movies are hugely popular in China, and the franchise is a huge money-maker for Universal Pictures. The studio was looking at a major revenue loss. Cena promptly posted an abject apology, in Mandarin, saying, “I made a mistake. I’m so, so sorry for my mistake. I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m very sorry.”

While the John Cena episode showed the cost of making statements that offend Chinese authorities, turning a blind eye to genocide also carries a risk. Disney’s live-action remake of the Mulan film was partly filmed in Xinjiang, and the producers credited the police bureau in Turpan, a city in Xinjiang with a large Uyghur population. When human rights advocates noticed the credits, Disney came in for severe criticism.

“This film was undertaken with the assistance of the Chinese police while at the same time these police were committing crimes against the Uyghur people in Turpan,” Uyghur activist Tahir Imin told The New York Times. “Every big company in America needs to think about whether their business is helping the Chinese government oppress the Uyghur people.”

FOR U.S. CORPORATE EXECUTIVES, it is the allegations about forced Uyghur labor practices that most complicate their dealings in China. Unlike the egregious slave labor practices in the 1930s and 1940s in Nazi Germany, China’s worker policies are hard to see, but evidence suggests they are still horrific.

While Chinese authorities say that many Uyghurs sent to “re-education” centers have subsequently been assigned to work in cotton fields or factories as part of a “poverty alleviation” program, human rights investigators insist that Uyghurs have little or no choice over whether to accept such work, because the alternative is continued detention. Satellite photos show the factories are often located inside the detention camps, surrounded by high walls and barbed wire. Two formerly detained Uyghur women who cooperated with a BuzzFeed News investigation said they worked in locked cubicles on such tasks as sewing pockets on work clothes. They stayed in factory dormitories, with as many as 16 women packed in a room, and in their spare time they were expected to study Chinese President Xi Jinping’s speeches. The grueling work of picking cotton by hand, meanwhile, was largely done by Uyghur prisoners or former prisoners.

American consumers bear a share of responsibility for such practices, insofar as they buy inexpensive clothing made in China over made-in-USA alternatives. A 2011 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found that 36 percent of U.S. consumer expenditures on shoes and clothing were for products made in China, versus just 25 percent for apparel made in the U.S., and a further 2019 study suggested that the numbers continue to climb. It is virtually impossible to know for certain whether a particular T-shirt or pair of sneakers was produced through forced Uyghur labor, but items containing Chinese cotton are suspect.

Investigations by the U.S. Congressional-Executive Commission on China and the Tech Transparency Project found that Nike, Adidas, H&M and Calvin Klein, among other companies, were tied indirectly via their suppliers to forced Uyghur labor. The companies all said they had no evidence of forced labor in their Chinese operations, although some acknowledged they were familiar with the stories. Such reports put the companies in a bind, caught between criticism from human rights groups on one side and the wrath of the Chinese government on the other. After Adidas and Nike expressed general concerns about forced labor, Chinese sales of their products plunged. A Wall Street Journal investigation found that some companies, including North Face, Calvin Klein and Victoria’s Secret, walked back their criticism after the Chinese reaction.

H&M experienced even greater backlash. The Swedish firm actually went beyond statements by the U.S. companies, saying it was “deeply concerned by reports from civil society organisations and media that include accusations of forced labour and discrimination of ethnoreligious minorities in Xinjiang…” Communist authorities immediately wiped references to the company off its e-commerce, ride-hailing and map applications, and Chinese nationalists mounted a counter-campaign on Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter, under the hashtag “I Support Xinjiang Cotton.” The campaign is said to have received 1.8 billion views, though some of the traffic may have been driven by the government’s manipulation of social media platforms.

American companies now face new scrutiny from Congress. A proposed Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act would require the U.S. government to ban the import of goods manufactured in the Xinjiang region unless U.S. Customs and Border Protection establishes that the goods were not produced through the use of forced labor. In addition to companies producing goods with Chinese cotton, electronics manufacturers, solar energy companies and other technology businesses could be affected.

Such a law could conceivably have real impact. But according to Congressional staff and lobbying records, Nike and some other companies are pushing for changes in the proposed legislation. They point to the opacity of Chinese supply chains, which gives them limited ability to investigate their suppliers. The president of the American Apparel and Footwear Association, Stephen Lamar, testified in Congress that a U.S. import ban on products from the Xinjiang region could “wreak havoc” on its operations. He noted that a fifth of the world’s cotton supply comes from fields in Xinjiang, and the fibers are often intermingled with cotton grown in other countries. Neil Bradley, executive vice president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, argued in a letter to the House that previous efforts to require companies to probe the origin of their imported products were “nearly impossible” to comply with due to “the absence of qualified inspection and audit systems.”

COMPANIES ARE NOT the only American entities that find it awkward to denounce or even acknowledge Uyghur repression. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 370,000 Chinese students were enrolled in U.S. colleges and universities. Chinese students typically pay full tuition in cash, and a recent Wilson Center study noted that the surge in Chinese enrollment was a boon to schools “starved of revenue at the state level since the 2008 recession.” The question is whether such a dependence on tuition income from Chinese students can compromise a school’s independence.

“Many colleges and universities have exchange programs with Chinese universities, and some host Chinese officials in their public policy programs,” says Rayhan Asat, “but that should not mean a loss of academic freedom. Many professors are quick to criticize the moral shortcomings of the U.S. government,” she says, “but when it comes to China, they shy away from their proclaimed principles. Academic institutions need to maintain their integrity.”

According to the Wilson Center study, some pro-Beijing students have pressured their U.S. universities to cancel academic activities involving content related to China they consider controversial and to force faculty to alter language or teaching materials considered offensive to Chinese nationalists. Asat herself encountered such a situation in November 2020 when she took part in an online discussion at Brandeis University. In the midst of her presentation, Asat’s computer screen was taken over by pro-Beijing students, who wrote “fake news” and “liar” on it.

According to a report on the incident by Voice of America News, the pro-Beijing students at Brandeis even adopted the language of student activist movements. A local branch of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association issued a statement saying the term “cultural genocide” was offensive to them and that using it could “make all Chinese students insecure.” Some Chinese students argued that the Uyghur event violated the university’s official commitment to promote “diversity and inclusion” inasmuch as it created a hostile environment for them.

While the Chinese authorities do not select which students come to the U.S., the Wilson Center study reported that students are encouraged to defend Chinese national interests abroad. Those who demonstrate loyalty to Beijing may be rewarded with professional benefits, while those seen as disloyal may be banned from returning home and lose scholarships.

Among those concerned about Chinese activities on U.S. campuses are leaders of the College Republican National Committee and the College Democrats of America. In a rare show of solidarity, they issued a joint letter in May 2020 writing that “the Chinese government’s flagrant attempts to coerce and control discourse at universities in the United States and around the world pose an existential threat to academic freedom as we know it.” They specifically cited Chinese government efforts to censor discussion of issues such as the persecution of the Uyghurs and other minority populations.

THE UNITED STATES and its allies eventually went to war against Nazi Germany—not to stop the genocide of the Jews but because of Nazi military victories throughout Europe and the threat of Axis world domination. It is hardly conceivable that anyone will attack China in order to help the Uyghurs—or for that matter, the people of Tibet, the residents of Hong Kong, or Han lawyers or journalists and political activists held in China’s prisons.

Western countries are looking instead at a coordinated international sanctions campaign, with the goal of pressuring China to change its policies toward the Uyghurs. In March 2021, the United States, Canada and the European Union jointly agreed on limited sanctions targeting some Chinese officials over their connections to Uyghur repression. The E.U. moved first, banning four Chinese officials from traveling to E.U. countries, freezing their personal assets, along with those of a Xinjiang police bureau, and barring them all from receiving E.U. funds. The U.S. government added two more Chinese officials to its sanctions list.

Sanctions generally have been seen as a blunt policy instrument when it comes to pressuring countries to end their human rights abuses, but an argument can be made that targeting specific individuals can be effective. “Wealthy individuals like to park their money in the West,” says Michael Abramowitz, the president of Freedom House, a Washington-based democracy watchdog group. “Even the Chinese send their kids to school in the West. So targeted sanctions may have more impact than more general ones.” Separately, Georgetown’s James Millward makes the argument that a sanctions regime “injects pressure into a system.” He cites the surge in online traffic driven by the nationalist pushback against criticism of forced labor in Xinjiang. “Some of it was, ‘Wait a minute. What’s this issue with Xinjiang cotton?’ Sanctions can actually shine a spotlight on something.”

One factor that could limit the use of a globally coordinated series of sanctions is that China is quick to react against any country that challenges it. As the Trump Administration was leaving office, China sanctioned 28 senior American officials whom it held responsible for anti-China rhetoric and policies, including Pompeo. The Chinese government also reacted sharply to the European Union, imposing punitive sanctions of its own on several of its most outspoken European critics. Neither move had much of an impact, however. The European Parliament immediately warned China that it would not ratify a pending business investment deal that China wanted until the sanctions were lifted.

Nor were the sanctioned U.S. officials especially alarmed. Among them was Keith Krach, the first U.S. official to publicly say China’s treatment of the Uyghurs amounted to genocide. “I am not going to bend a knee to Emperor Xi, and I don’t think anybody else should either,” Krach tells me. He says his father, a small business owner, had to lay off workers because of competition from China.

Non-Western countries may be less able to stand up to Chinese pressure. Advocates for the Uyghur cause, for example, are dismayed by the lack of support from majority Muslim countries. When Jonathan Swan of Axios asked Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan in June 2021 why he had not acknowledged Chinese abuses against the Uyghurs, given that his country is 96 percent Muslim, Khan suggested his government was not inclined to challenge China over the Uyghurs as long as it was receiving Chinese aid. “China has been one of the greatest friends to us in our most difficult times,” Khan said, “When we were really struggling, our economy was struggling, China came to our rescue. So we respect the way they are and whatever issues we have, we speak [about] behind closed doors.”

Some Muslim majority countries have even praised China’s treatment of its Muslim citizens. A 2019 joint letter signed by 23 Muslim countries accepted China’s description of its Uyghur detention camps as “vocational education and training centers.” The biggest disappointment to Uyghur exiles has been the lack of support from Turkey, which shares linguistic and cultural ties with the Uyghur people. In 2009, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan declared that China was committing genocide against the Uyghur people and called on Chinese authorities to show more “sensitivity.” The Turkish government at the time was providing safe haven to tens of thousands of Uyghurs, supporting many of them with education and housing.

After he became Turkey’s president in 2014, however, Erdogan’s policy toward the Uyghurs began to change. The country was experiencing an economic crisis, and relations with the United States and Europe were deteriorating, largely because of Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian policies. China took on new importance as an ally and benefactor. In 2018, China loaned Turkey $3.6 billion to help it deal with a plunge in the value of the Turkish lira. But the aid came at a heavy price: Turkey essentially had to turn its back on the Uyghurs. They soon found themselves under suspicion in the country that once had welcomed them. In 2017, Turkey signed an extradition treaty with China and, in the years since, hundreds of Uyghurs have been detained and sent back to China.

With the Taliban conquest of Afghanistan, which borders the Xinjiang region, some counterterrorism experts have been reminded of earlier Chinese warnings about Uyghur Muslim militancy. Chinese security officials have previously claimed that the Taliban provided arms and support for Uyghur “separatists.” Taliban leaders, however, are on generally good terms with the Chinese government and, as is the case with other Muslim countries, their need for aid and investment from Beijing could well curb any inclination to give even rhetorical support to their fellow Muslims in Xinjiang.

The United Nations, meanwhile, is virtually powerless to take action on behalf of the Uyghurs. While China is a signatory to the 1948 Genocide Convention, it expressed a reservation on Article IX, which provides that the International Court of Justice is authorized to investigate possible genocide cases. The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, has been negotiating for access to Xinjiang since 2018, but so far without success.

It is hardly conceivable that anyone will attack China in order to help the Uyghurs.

Chinese President Xi Jinping (center) with foreign leaders (including Pakistan’s Imran Khan, fourth from right) at the inaugural China International Import Expo in 2018. Credit: Wikipedia

THE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMUNITY is itself divided over whether publicly challenging Chinese authorities over Uyghur repression is an effective strategy. After the 2015 arrest of Wang Yu, a Chinese lawyer who defended Uyghur economist Ilham Tohti, the American Bar Association (ABA) faced a dilemma over how to respond.

At the time, the ABA maintained an office in Beijing as part of its Rule of Law Initiative (ROLI) to support the work of Chinese defense lawyers, grassroots advocates and some government agencies, especially in the area of environmental reform. ABA lawyers also provided training for Chinese judges on how to handle domestic violence cases and advised local NGOs on how to promote the rights of people with disabilities. Such work required the acquiescence of the Chinese government, and ABA staffers were sometimes torn between an impulse to denounce government repression and the need to keep a low profile in order to continue their work.

After waiting more than three weeks following Wang Yu’s arrest, the ABA issued a statement saying it “encourages the Chinese government to permit lawyers to discharge their professional duty….” The relatively mild tone of the statement disappointed human rights advocates outside China, including Amnesty International, but it reflected the concerns of the ROLI management and staff in Beijing that their work in China could be endangered by something stronger. The ABA leadership in the United States, however, guided by the organization’s own Human Rights Committee, decided to give Wang Yu its human rights award. The Chinese government reacted angrily, and the ROLI staff in Beijing had to suspend operations temporarily, just as they had feared.

“If we had been able to continue our work in China, there’s a decent chance we would have had information about the human rights situation, and there would have been channels to connect people with that information,” says one former ABA staffer who worked on the ROLI project in Beijing but wishes to remain anonymous. “Calling on independent organizations like ABA ROLI to stand up and speak from a perspective of pure moral righteousness only means you will lose crucial modes of engagement.” The ROLI staff were able to reopen their Beijing office later but were forced to close it in 2016 in response to China’s passage of a law restricting the work of foreign NGOs.

A different kind of concern about losing engagement opportunities with China may now be eroding some of the bipartisanship previously evident in support for the Uyghur cause. For many progressives, the global threat of climate change is the top issue in dealing with China. A joint letter in July by more than 40 progressive environmental organizations asked the Biden Administration and the U.S. Congress “to eschew the dominant antagonistic approach to U.S.-China relations and instead prioritize multilateralism, diplomacy, and cooperation with China to address the existential threat that is the climate crisis.” The letter made no mention of the Uyghurs.

“It’s a real problem that the international pressure on human rights in China is coming from the U.S. and Western allies,” says Tobita Chow, director of the group “Justice Is Global,” one of the signatories to the July letter. “At the end of the day,” he says, “it’s the internal critics of repressive policies in Xinjiang, within China, that are going to have a much bigger impact on those policies than anything we can do from the West.”

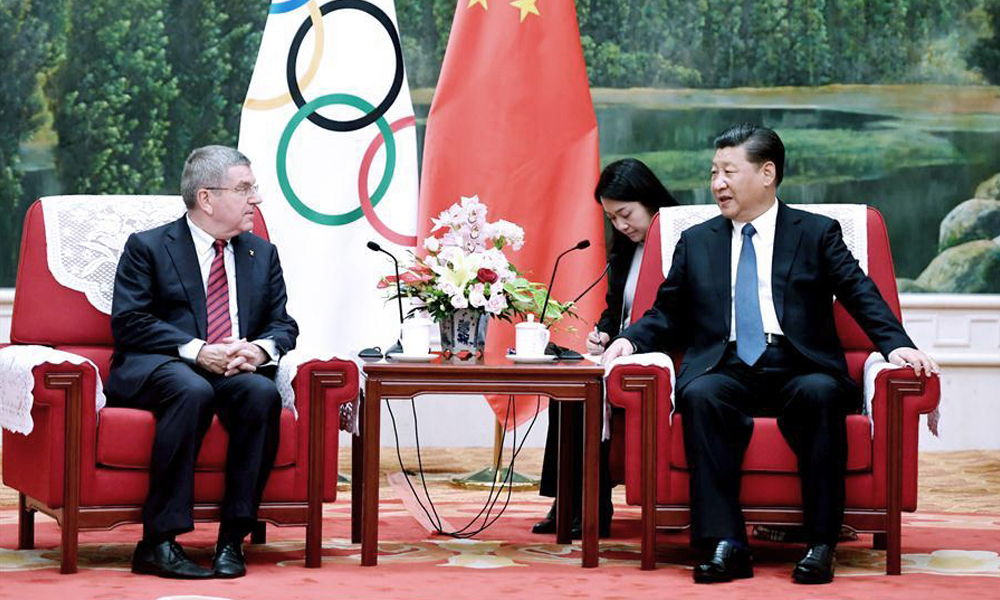

Uyghur exiles and their advocates in the West, however, do not believe they can count on internal critics and are not about to stop talking about what is happening in Xinjiang. Preparations for the 2022 Beijing Olympics have sharpened the debate over how to fight for Uyghur rights. A movement of Uyghur exiles and progressive Jewish organizations called the Berlin-Beijing Coalition is highlighting how Hitler used the 1936 Olympics to advance the Nazi cause and arguing that countries should not let Beijing do something similar in 2022. Among those agreeing with that view is Freedom House’s Abramowitz, who previously served as director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s public education programs. “I think it’s an abomination to have the Olympics in China, given the credible case of genocide against the Uyghurs,” he says.

The Chinese government has, through its own actions, made the Beijing Olympics into a referendum on the Uyghur genocide. The world’s athletes should not be expected to compete against the backdrop of concentration camps.

Uyghur exile Rayhan Asat has also argued passionately for a boycott of the Olympics, as has Nury Turkel, a Uyghur lawyer based in Washington, DC, who now serves as vice-chair of the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. “The Chinese government has, through its own actions, made the Beijing Olympics into a referendum on the Uyghur genocide,” Turkel wrote in a recent Foreign Affairs column. “The world’s athletes should not be expected to compete against the backdrop of concentration camps.”

When the Congressional Executive Committee on China took testimony in July 2021 from representatives of the leading corporate sponsors of the Beijing Olympics, including Airbnb, Coca-Cola, Intel, Proctor & Gamble and Visa, none was willing to say a boycott was appropriate. “I was heartbroken,” says Rushan Abbas, who followed the testimony as executive director of the Campaign for Uyghurs. Her sister, a medical doctor, was detained in 2018 while Abbas was in the United States advocating for Uyghur rights, and she is convinced her sister’s imprisonment came in retaliation for her activism. “My sister is sitting in some dark dungeon somewhere,” she says, “and these corporate representatives are afraid of saying one word against Beijing.”

For all the Uyghurs who have family members or friends languishing in detention camps or prisons or who live in constant fear of being erased, taken away or forced into servitude, indifference to what is happening in Xinjiang is an affront not just to the Uyghur people but to all those who have ever experienced such persecution. With their testimony and their pleas to be heard, they remind the world of a simple imperative: In the face of a genocide, the answer must be, “Never Again,” no matter the complications and inconvenience it may bring.

Tom Gjelten, a correspondent for NPR News for 38 years, covered international and domestic affairs.

One thought on “An Inconvenient Genocide”

My thoughts on the appeasement of China can best be described visually by a piece of historical digital art I recently made. You can view it here. https://www.thucydd.com/appeasing-the-last-emperor-of-china