by Daniel Ross Goodman

“Humility is not thinking less of yourself,” said C.S. Lewis, “but thinking of yourself less.” But perhaps C.S. Lewis should’ve added that humility is also recognizing your limitations – a skill sorely lacking in many athletes and entertainers. Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player of our time, infamously tried his hand at baseball for a mediocre eighteen-month stretch before returning to the hardwood. ‘Well, I am the greatest sports-player in the world,’ Jordan may have thought at the time. ‘How hard could it be?’

“Humility is not thinking less of yourself,” said C.S. Lewis, “but thinking of yourself less.” But perhaps C.S. Lewis should’ve added that humility is also recognizing your limitations – a skill sorely lacking in many athletes and entertainers. Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player of our time, infamously tried his hand at baseball for a mediocre eighteen-month stretch before returning to the hardwood. ‘Well, I am the greatest sports-player in the world,’ Jordan may have thought at the time. ‘How hard could it be?’

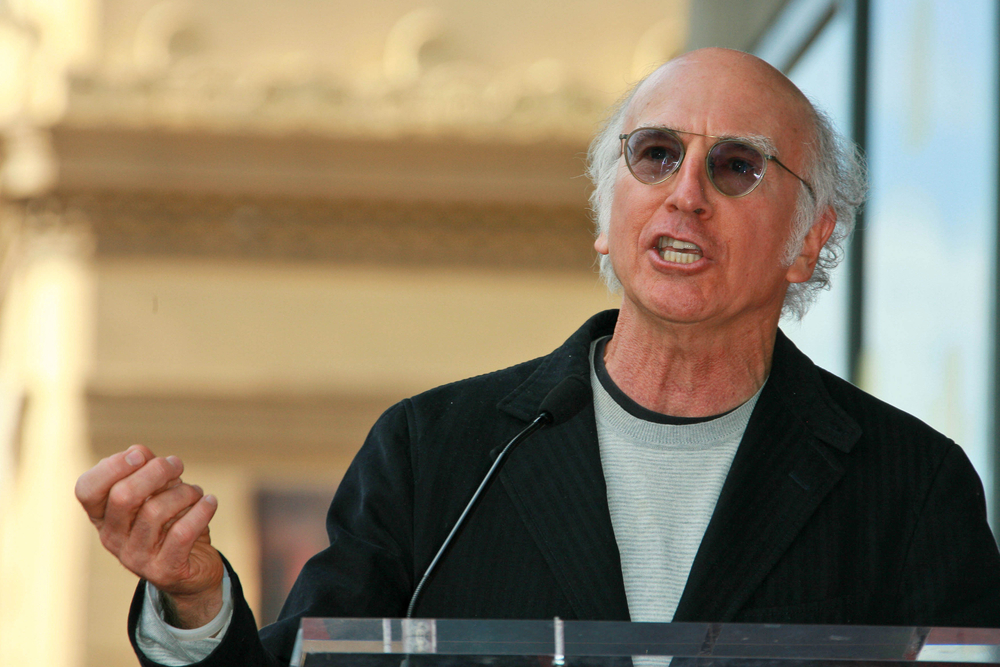

Larry David is the greatest television comedy writer of our time. No other comedic mind has written two mega-hit TV comedies, the iconic Seinfeld in the ‘90’s, and the uproarious Curb Your Enthusiasm in the 2000’s. Seth McFarlane (Family Guy) flopped with The Cleveland Show, and Matt Groening (The Simpsons) had moderate success with Futurama before it flamed out. In the world of TV comedy writing, Larry David stands alone.

Thus, it was with great curiosity that the entertainment world learned that Larry David would deign to try his huge hand at Broadway. (He really does have peculiarly huge hands.) But this development is not so strange; after all, several years ago, Trey Parker and Matt Stone tried their brilliant hands at Broadway, and the result was the equally brilliant The Book of Mormon.

For a TV comedy writer to write a hit Broadway play, then, would not be unprecedented. And Larry David’s Broadway try is a rather good one. Michael Jordan trying to hit a curve he is not; eight seasons on Curb turned David into a capable, clever, and surprisingly skillful actor. But his comedic art flourishes best on the screen, not on the stage.

First, David does not have the voice for theater. It is too soft, and it is difficult for him to project in the ways that are necessary for a theater actor. This fact is painfully evident when compared with the strong voices of his theater-trained counterparts. On television, we don’t notice when one voice is weaker than another, but on stage, actors’ voices are naked, unfiltered by the audio magic of TV sound editing. David also doesn’t seem to know what to do with his strangely large hands. On screen, a camera allows for hands-hiding close-ups; on stage, no part of the body can hide from prying viewers’ eyes.

Secondly, part of the reason David’s humor works so well on TV is because it can be synchronized with musical cues, much in the way musical cues make horror movies far scarier. Curb’s score subtly but significantly heightened every humorous moment. Without these cues, David’s comedy fails to hit home in the same way.

And third, on stage, Larry David’s best lines are interrupted by applause, in contrast to the laugh-track-free Curb. So, when the moment that everyone was waiting for finally came—when he uttered his trademark “pre-tty, pre-tty, priiiiiihty good” line—interrupting laughter made it fall flat.

Moreover, while the rest of Fish’s professionally trained theatrical cast is stellar, Larry David has nowhere near the kind of chemistry with them as he had with the cast of Curb. I cringed during the conversation scenes between David and Ben Shenkman (who plays his brother), not because Shenkman was bad, but because it would have been so much better between David and Jeff Garlin, David’s battery-mate on Curb.

All of this is not to deny that the play is funny. David plays Norman Drexel, a Los Angeles urinal salesman whose life is upended when his father dies, his mother moves back in with him, and his housekeeper apprises him of an embarrassing secret about his father that she had hidden for years. The play is an extended Curb episode made for the stage, but without the rest of the Curb cast that made that show great. It’s also somewhat of a parody of conventional father-son struggles, simmering-and-now-surfacing familial secrets and resentments that so often suffuse the stage. Part of me wonders whether David wanted to title the play Death of a Urinal Salesman’s Father until he was talked out of it.

Fish is filled with familiar Seinfeldian and Curbesque comedic dilemmas—‘am I supposed to tip my father’s death-bed doctor?’—and other old standbys, like the microscopic scrutinizing of language and idioms (“‘walk the talk’?! You can only walk the walk, or talk the talk, you can’t ‘walk the talk’!”), and the comic incongruities between the poignant and the petty that were mined so often and so successfully in David’s two seminal shows. The script also contains a fair amount of darker, Woody Allen-ish humor, with gloomy gems like “The only time I feel truly alive is at funerals. It’s like life is a single-elimination tournament, and I moved on to the next round,” and the mordantly misanthropic “I don’t wanna die alone. I wanna live alone—I just don’t wanna die alone.”

Though Fish in the Dark is droll and diverting, it’s nowhere near as sidesplitting as Curb—it’s not even as good as a Curb episode staged for the theater (which could be a great idea, by the way).

“Imperfect love must not be condemned and rejected, but made perfect,” states a character in Iris Murdoch’s The Bell. Larry David’s imperfections as a theater actor should not be mocked and maligned; he should be admired for his bravery to venture out of his element. And the incorrigible creator of Curb should be commended for his courteousness—after the show, he mingled with fans, signed autographs, and took pictures for a good twenty minutes.

Larry David’s run with Fish in the Dark lasts until June, whereupon Jason Alexander, better known as George Costanza from Seinfeld, will replace him. Alexander’s Seinfeld character, George, was essentially a fictionalized version of Larry David, and the irony of David’s career is that George was always a better version of Larry David than Larry David; David is a transcendent comedic writer, but Alexander has always been the better actor. Thus, when David does step down from the stage, no one will be surprised if Fish in the Dark becomes a better version of the play that David wrote. David’s Fish is a funny and entertaining Broadway pitch; unfortunately, it’s juuust a bit outside.