Should a jealous Jewish store owner keep tabs on his beautiful young wife, seemingly smitten with “a college man”? Can the women of Pereyeslav, a Ukrainian town, hold back from causing catastrophic tsuris and tumel because a young scoundrel made poor Rochel pregnant? Does suicide run in Motl’s family?

Not the sort of dilemmas that Secretary of State nominee Antony Blinken will confront in the Biden administration, although he may know about them. They’re a few of the plot predicaments spun off by his great-grandfather, Meir Blinkin (1879-1915), the Yiddish fiction writer who burned bright among immigrant Jewish-American writers in the early years of the 20th century until the literary world, in the words of Yiddish scholar Ruth Wisse, left him “gradually forgotten and his work neglected.” The family changed the spelling of its surname in the next generation.

Meir Blinkin came to the United States in 1904 at age 25, later bringing over his wife and two sons. Educated in a Jewish primary school and a Kiev trade school and then briefly trained in medicine, he earned his keep in Manhattan by carpentry and masseur work while publishing some 50 fiction and nonfiction pieces in the decade before his death. Prominent colleagues eulogized him on the steps of the Jewish Daily Forward’s Lower East Side building on the day of his funeral.

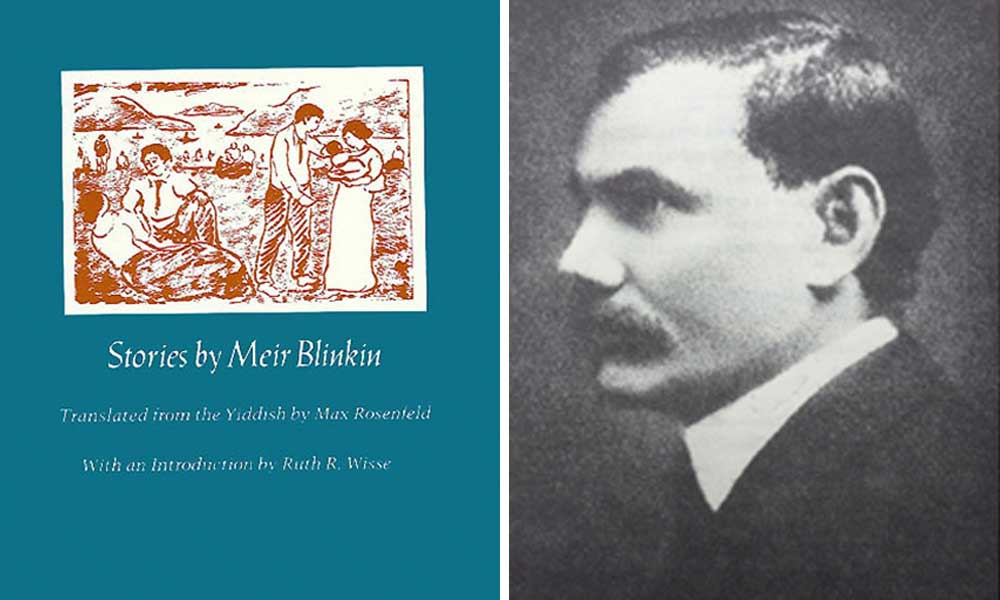

Cover of Stories by Meir Blinkin.

Wisse, in her introduction to the only English-language volume of Blinkin’s work, Stories (SUNY Press, 1984)—translated by Max Rosenfeld and shepherded into print by Maurice Blinken, the writer’s son—wrote that “no Yiddish writer of the period” brought “such subtle and concentrated attention” to the psychological nuances of newly arrived, Yiddish-speaking immigrants in New York and characters still in the old country.

Reading that 1984 edition of Stories almost four decades later, one finds that Blinkin’s wry intimacies resemble those of the greatest of them all—Sholem Aleichem—and why shouldn’t they? The two came from the same town—Pereyeslav. Reading Blinkin, you sometimes hear Fiddler in the background. And yet his stories remain modernist,

fast-paced, alive, whether set in New York or der heym (back home). In the lengthiest, “Card Game,” first published as a novella, Moyshe, a Manhattan store owner suspicious of his wife, considers moving “far out in the Bronx,” where life would be “less exciting” and pose “fewer temptations.” He’s wise about human nature and keeps an eye on Yudin, that “college man” friend who is fond of his wife. Still, Moyshe stays hopeful that Fanya, his “Fanyetchka,” might still want him, noting that “his wife had come to realize that a husband is still a man.”

Most of the tales take place back in Pereyeslav or close by, where people talk about salacious things “more with their eyes than with their lips,” where the marketplace stalls stand “so close together they seemed to be holding hands.” Violations of custom still produce danger. In “Dr. Machover,” Moyshe-Dovid, destined to become a prophet or scholar, turns rigidly secular after finding, in an old book of ethics, an inscription that declares, “There is no God, there is no hell, there is no paradise. It is all falsehood and lies!”

Blinkin’s spry lines and images often stick in the mind and turn up in every story. In “The Mysterious Secret,” lovely Shifra, unnerved by all the townsmen infatuated with her and perplexed by what in people “compels them to lie,” puts her hand on her suitor Nochem’s throat and says, “I want to hear how your voice sounds when you’re telling the truth.”

As Wisse notes, Blinkin shared the modernist style and contempt for primness of Di Yunge, the fledgling Yiddish-American poets of the early 20th century. He laces his stories with infidelity—particularly by strong, married women—and occasional violence. Fradel announces her own principle in “Family Life,” after Shloyme, brother-in-law of her husband Meylekh, waits for Meylekh to leave for work in the morning so he can slip in and make love with her: “Let him do whatever he wants,” she crows, “and we’ll do whatever we want.”

What stays with a reader is Blinkin’s descriptive freshness, playful asides and intermittent stabs at everyday wisdom. In “A Simple Life,” we learn that Avrom-Chaim “loved very much to walk with the older men and was careful not to take longer steps than they did.” When the narrator of “Incomprehensible” visits an Odessa brothel, the madam, certain of who should accommodate him, takes him to the room of a young woman who reads the great I. L. Peretz and keeps “pictures of several classical Yiddish writers hanging on the wall above her table.”

“What are you doing in a place like this,” he blurts out. “What are you doing in a place like this?” she shoots back, the emphasis saying everything.

Our new secretary of state nominee would bring more remarkable Jewish family lore to his office than any Foggy Bottom predecessor. He has spoken often of how his grandfather, Maurice, fled pogroms in Eastern Europe. His stepmother, Vera Blinken, fled communism in Hungary. His late stepfather, Samuel Pisar, was the sole survivor of 900 students from his grade school in Bialystok, Poland. Pisar’s “lifelong work as peacemaker,” Antony Blinken has said, constituted “his answer to a childhood lost to the Holocaust.”

At his presentation by President-elect Biden as the next secretary of state, Blinken told the tale of how Pisar, after four years in concentration camps, broke from a death march and escaped into the Bavarian woods. Eventually spotting an American tank, he ran up to it, and an African-American GI opened the hatch and looked down at him. Pisar, recounted Blinken, “fell to his knees and said the only three words in English that his mother had taught him: ‘God bless America.’ The GI lifted him into the tank, into America, into freedom. That is who we are.”

Antony Blinken doesn’t talk as much about his great-grandfather, his elter zeyde, but he clearly hasn’t forgotten him. The man in the first photo of several in a roughly two-minute video he tweeted in December under the aegis of the Biden-Harris transition…Meir Blinkin.

What might he take from his great-grandfather? In “A Simple Life,” Avrom-Chaim, lifelong tailor and mensch, reflects on “the topsy-turvy order of the world, where everything was just the opposite of what it should rightfully be.” Not a bad place to start.

Opening Picture: Antony Blinken in the Embassy of Moldova. (Photo credit: Wikimedia)

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.