It was a rainy day in Arad, one of the driest places on earth. I was on my first trip to Israel since becoming editor of Moment. It was February of 2008. A friend insisted I needed to meet Amos Oz (1939-2018). Amos was the soul of Israel, he said.

He had given me Amos’s phone number. I called and Amos said, “Come to my house.” And so, with my teenage son, Noah, as traveling companion, I caught a bus at Tel Aviv’s dilapidated central bus station. We sat right behind the driver so we could watch the Negev pass by through the windshield. The rain pelted; the driver had the wipers on for most of the trip.

After a couple of hours he dropped us off at a deserted bus station. All the stores were closed; I can’t remember why. I do recall that it was cold and dreary, I was coming down with a cold, and my son was restless.

Arad seemed gray, empty. We found the street and after a while the house, a mid-century house identical to others on the street, built in an era of cheap construction. The street made me think of those on the planet Camazotz in A Wrinkle in Time.

All the while, it was raining and we were unprepared for the chill, huddled in light jackets.

The front stoop seemed uninviting, and although I felt awkward, I rang the bell nonetheless. A dark-haired woman opened the door, and warmth poured from the yellow angle of light inside. It was Nily, Amos’s wife of 48 years. The warmth emanated from her, not the light.

We were hungry. Chicken soup was on the stove, and as soon as we were settled at the table, she ladled the rich broth into bowls. We devoured it and felt fortified.

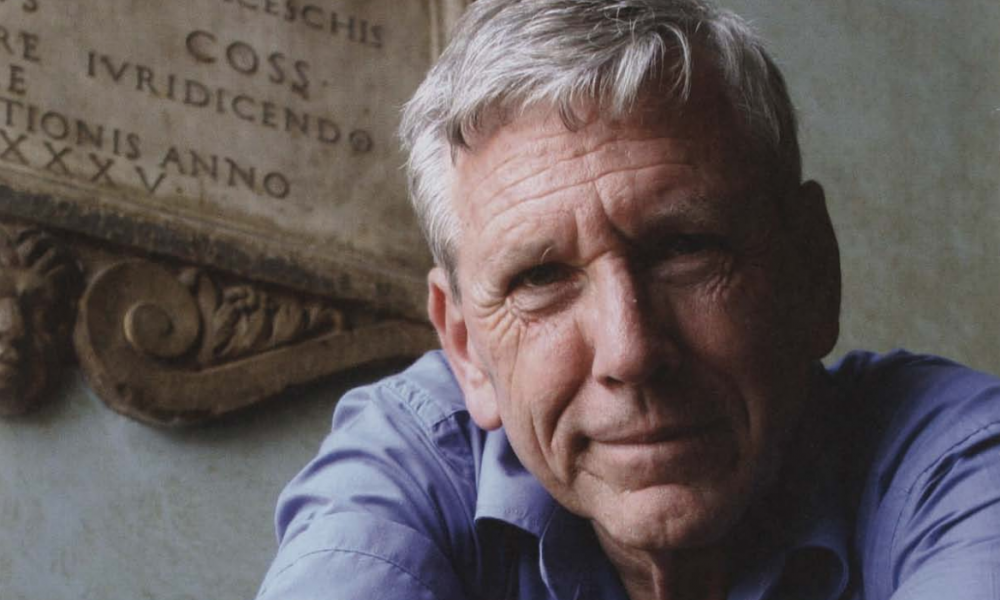

Amos, wearing a sweater (I think gray), padded down a narrow hall and greeted us. There was the rugged literary face lit by the famous blue eyes. The well-spoken American English. After we finished our soup and other treats that followed, we went downstairs to his basement lair.

The walls were covered with books. There was a sliding glass door, but the dark day outside didn’t intrude. I set up my tape recorder. We talked for a long time about his reading of history, his hopes for Israel.

His hopes hung on the metaphorical divorce he often spoke about. The divorce between the Israelis and Palestinians, which needed to happen, he explained. They could not share the same small apartment forever. No one was moving out. And it was necessary to decide who would get bedroom A and who would get bedroom B. And since the apartment was so small, special arrangements needed to be made about the kitchen and bathroom. It was all very inconvenient, but the alternative was too terrible. It was just a matter of time, so why not get it done with?

It was a common sentimental mistake, he said, that the hatred had to be cured and friendship forged before the divorce. Throughout history, peace has worked the other way around. Peace is made between enemies, with clenched teeth and bad intentions. Then eventually there occurs an emotional de-escalation, the healing process. It could take generations.

The state is not a holy object. A good leader—not one who thinks he is the mightiest in the world, but one who knows that his job is to persuade people to do things they don’t want to, or are afraid to do, or would like to delay doing—can achieve this.

He knew something about compromise, he said, having been married to the same woman for 48 years.

He took a lot of time with me. And with my son, who was half reading a book as Amos and I talked. I couldn’t tell how much he was absorbing at the time, but Noah, the child of a divorce, was listening and observing. He remembers Amos’s divorce metaphor and that Amos was very sure of himself, kind, yet weary.

For me, Amos’s perspective was comforting. At the time, Ariel Sharon was lying unconscious in a hospital bed after suffering a massive stroke following Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza. Ehud Olmert was prime minister, and Israeli politics were in turmoil, although the prospect of peace had not yet completely vanished. Here in the dim, musty room, surrounded by books in this modest home in this development town where Amos and Nily had moved for their son’s asthma, I felt safe. This was my Israel: an Israel of wisdom, hope and understanding, where peace was a goal, a rational goal.

I’m sure Amos was imperfect, as all humans are—especially the great ones, because we hope for more from them—but as he talked, I wished he could be Israel’s prime minister. I wanted a wise writer to lead the way. He knew how to lead and how to instill hope.

I couldn’t help but ask him about this. He told me that Vaclav Havel, the writer who became the Czech Republic’s first democratically elected leader, had asked him the same question. He said he told Havel that if all writers went into politics, the politicians would write the novels, and that would be the end of civilization as we know it.

It was a joke, but he was serious. Writers have their own role, and he had fulfilled his. But I understood that when it came down to it, he didn’t have the hunger for power. He was content to be an outside insider, an influencer, a counselor.

He told us he was going to drive us around the hills near Arad, show us places we needed to see, but night fell and with the rain still coming down, he never did.

We ate more, then had to get back to Tel Aviv. Instead of a bus, Amos arranged for a driver. Nily packed up food for us for the trip. It was a haimish day with haimish people.

I was yet another stranger stopping by for wisdom, to see and hear Israel through his eyes, in person. It was, in retrospect, one of many pilgrimages I made to meet the lions and lionesses of the secular Jewish world, the thinkers. One by one they are leaving us alone to find our own way.