The Courage of Eric K. Ward

How a Black punk rocker from Southern California confronted white nationalists, linked anti-Black racism with antisemitism and took the national stage to fight for inclusive democracy.

In the late 1970s, a Black police detective in Colorado named Ron Stallworth infiltrated a local chapter of the Ku Klux Klan by impersonating a white racist on the telephone, including in several conversations with David Duke. When face-to-face meetings were necessary, he sent a white undercover narcotics officer as his stand-in.

A decade later, Eric K. Ward, a Black community organizer doing field research on the far right, began infiltrating white nationalist groups in rural areas of the Pacific Northwest. But he didn’t send a proxy—nor did he have a stand-in at larger antigovernment, white supremacist events in the big cities of Oregon, Idaho, Washington State and beyond. He simply went himself. “A cardinal rule of organizing is that you can’t ask people to do anything you haven’t done yourself,” Ward says. And so, throughout the 1990s, he spent a fair amount of time among people he describes as “plotting to remove me from their ethno-state.”

Ward has seen violence up close. He’s had weapons drawn on him and threats made on his life, but he chooses not to dwell on those experiences, except to say that to this day he’s nervous to sit with his back to a window or front door. “I don’t want to overstate it, but many of us are left with marks from that period,” he notes, referring to other field organizers and antiracist activists he’s worked with in his 30-plus-year career.

One story he does share took place in 1995 in Seattle at the Preparedness Expo, a four-day event that drew a hodgepodge of antigovernment tax protesters, Christian nationalists, alternative health enthusiasts, survivalists and racists. It was an encounter with a vendor there that illuminated what has become Ward’s powerful and unique thesis: that antisemitism is the foundation of the racism espoused by the white nationalist movement. And that achieving an inclusive, multicultural democracy requires going after those who promote antisemitic ideology.

“I’m not here to create hierarchies of oppression around anti-Black racism and antisemitism. What I’m here to say is that they’re killing us both.”

In Ward’s telling, he entered the exhibitors’ hall at the Seattle expo, where thousands of attendees were perusing all manner of literature and merchandise. “All of a sudden, I see this guy see me. This big, hulking guy in a baseball hat starts coming straight at me with purpose, and I’m thinking to myself, this is about to get interesting. He gets maybe five feet from me and stops and puts his hand out and says, ‘My name is Bear. And I’m so glad you’re here.’ And I look at him and say, ‘It’s nice to meet you, Bear. But I don’t shake hands with white people.’” (Of course, that’s not true, Ward is quick to note; the Black nationalist persona had come to him in the moment as a way to connect.)

“And he’s nodding his head, like he totally gets that,” Ward continues. The vendor asks him why he’s at the expo, and Ward says, “I’m here because I’ve been talking to other brothers…we’re preparing for collapse, and I’m just here to check things out.” The man reiterated that he was glad Ward had come and urged him to go see the next speaker, a retired cop from Phoenix named Jack McLamb, who had started a group called Police Against the New World Order. McLamb was pushing the need to build a broader alliance among, as the vendor put it to Ward, “Blacks and Orientals and Mexicans” to take on the federal government—and then to take on “the real problem.”

In his research on white nationalists, Ward had been collecting their printed material (“They loved their flyers. They probably killed more trees in the Pacific Northwest than anyone else,” he muses, while also recalling how truly vile the literature was). He’d begun to notice that along with anti-Black and anti-immigrant messaging, the flyers and pamphlets always included Jewish references—caricatures of Jews as puppet masters, Nazi symbols, and the like. So, when the expo vendor referenced the so-called real problem in America, Ward knew he meant the Jews.

At that moment, he decided he needed to figure out why this movement, which on one hand wanted to erase him and on the other sought his participation, was so fixated on the Jewish people.

Eric Ward is seated on a large stage in a low easy chair at Baltimore’s American Visionary Art Museum on an early fall evening in 2023. He’s here as part of a program on the power of art and storytelling to counter hate and help democracy flourish. Large in stature and wearing a stylish checked shirt and sports coat, Ward is sitting back in the chair that he earlier scooted closer to his interviewer. Soon he will lay out the thesis he’s been developing and articulating for some 30 years connecting racism and antisemitism—what he calls “the intersectionality of bigotry.”

But first, he looks out at the crowd that’s taking up an entire floor of the eclectic space. “I gotta tell you, I’m feeling a little nervous up here,” he says, grasping a hand-held mic in one hand. “Are you feeling it too?” Having witnessed Ward’s commanding stage presence at several prior events, I’m surprised to hear him say this. Others’ ears perk, bodies shift with interest. Suddenly, Ward’s leaning forward toward the rows of listeners. “But here’s the thing,” he says, breaking into a mischievous grin that borders on the conspiratorial, “my body cannot tell the difference between excitement and nervousness, right? So, I’m actually very excited to be here with you all tonight.”

That rhetorical refrain—punctuating sentences with “right?”—is just one of the ways Ward instinctively draws people in, creating an immediate sense of inclusion. In interviews he’s given to vivid, circuitous responses that are both expansive and personal, and while you may start to wonder if he’s forgotten your original query, his answer always comes around to it and often ends with him saying, “I feel like we could talk about this one question for an hour, right?” In public talks he is thoughtful and passionate, at times almost preaching to his audience. “Can you tell I grew up Southern Baptist?” he’ll ask, referring to his family on his father’s side, who came west from Kentucky. “We don’t know how to introduce ourselves in under 40 minutes.”

Today, Ward is a prominent national voice on civil rights and inclusive democracy and a go-to expert on authoritarian movements and hate groups. Whether he’s testifying before Congress in the wake of the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol; in conversation with Katie Couric and Doug Emhoff at the Aspen Ideas Festival; organizing on the streets of Portland, Oregon, where he lives with his partner Jessica, a fellow organizer; or writing and performing songs under his folk-punk alias Bulldog Shadow, Eric Ward seems to be everywhere. In 2023 alone, he spoke in 42 different cities, including in front of Jewish audiences large and small, where he’s become something of a rock star. In recent years, Ward has headlined American Jewish Committee events with Rabbi Angela Buchdahl and with Anti-Defamation League CEO Jonathan Greenblatt and toured synagogues across the nation. When he gave the 2023 Yom Kippur lecture to several hundred congregants at Temple Micah, a Reform synagogue in Northwest Washington, DC, he received a standing ovation. And after a brief Q&A with the congregation’s rabbi, he received a second one. “I don’t even know where to start,” a woman gushed to another attendee standing next to her. “He was amazing! So much to think about.”

Ward with Vice President Kamala Harris and Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff, December 2023. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Eric K. Ward)

Ward’s ascent to national prominence, however, is not a rock ‘n’ roll tale of meteoric rise but something closer to a zig-zag road tour, marked by myriad stops and diverse venues, forged connections and ventures down dark side roads, all guided by a deep commitment to social, economic and racial justice. “One of the attributes I deeply admire about Eric is his loyalty, not to X organization or Y person but to a mission of fighting for a world without hate,” says Greenblatt. He notes that Ward has stood with the ADL when others wouldn’t. “He’s taken blows for that courage. I don’t know that we appreciate what he has endured, but I have the deepest gratitude for his fidelity to principle. I wish we had more people like that.”

Again, Ward’s central premise, about which he speaks with great force and deep knowledge of both Jewish history and civil rights struggles, is that antisemitism, white nationalism and anti-Black racism are intertwined. It’s an idea he articulated in a prescient and oft-cited essay published in 2017 in the quarterly magazine The Public Eye, two months before tiki-torch-bearing participants at the Unite the Right rally shocked the nation, marching in protest of the removal of a Confederate statue in Charlottesville, Virginia, while chanting “THE JEWS WILL NOT REPLACE US.”

That essay is titled “Skin in the Game.” In it, Ward takes readers back to the 1960s, when white supremacy, which had been the law of the land, was toppled by a Black-led social movement.

Imagining the incredulity of those who came out on the losing end, he asks:

How could a race of inferiors have unseated this power structure through organizing alone? For that matter, how could feminists and LGBTQ people have upended traditional queer relations, leftists mounted a challenge to global capitalism, Muslims won billions of converts to Islam? How do you explain the boundary-crossing allure of hip hop? The election of a Black president?

Some secret cabal, some mythological power must be manipulating the social order behind the scenes. This diabolical evil must control television, banking, entertainment, education, and even Washington, DC. It must be brainwashing white people, rendering them racially unconscious. What is this arch-nemesis of the white race whose machinations have prevented the natural and inevitable imposition of white supremacy? It is, of course, the Jews.

This false narrative, Ward argues, endangers not only Jews and people of color but the very survival of an inclusive democracy. He also distinguishes between the white supremacists of old, who espoused a system that subjugated people of color, and today’s white nationalism, which he characterizes as a movement committed to their erasure—“and doesn’t care whether it does it through seizing power or terrorizing people of color and Jews out of this country.”

Ward’s story begins in Los Angeles, California, in the mid-1960s. In his words, it is the tale of “a punk rock kid living in poverty and surviving racism in Southern California.”

His parents were native Angelenos who divorced when he was five. As a child, Ward mostly lived with his mother, and when he was in 6th grade, they moved some 25 miles south to Long Beach.

She mainly worked in service jobs and at nonprofits, and for periods they lived at a motel. Ward says his mother followed the news but wasn’t particularly political; neither was his father, but he “definitely had a Black consciousness.” Ward situates himself as a child of the civil rights movement but also a Gen Xer, meaning that he is a product of 1970s and 1980s desegregation efforts and, at the same time, his was a generation of kids largely left to their own devices.

Ward circa 1973, Los Angeles, California. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Eric Ward)

“I grew up primarily in multiracial neighborhoods made up of Blacks and Latinos and poor white folks, and then soon to join them, South Asians,” he says. At the same time, he was bused to school in a middle-class white suburb “through the fanciest neighborhoods I’d ever seen, neighborhoods where white adults rolled down their car windows to call us monkeys or tell us to go back to Africa,” Ward recalled in a 2022 essay published in American Educator (“How I Came to Understand Racism in America—and What We Can Do About It”). In school he was sitting next to the children of California Governor George Deukmejian, and afterward he was going home to the motel room hoping there was something to eat. That inequality helped Ward begin to realize that racism and bigotry weren’t just individual acts but systems—some conscious, some not.

Which is not to say the individual acts didn’t also affect him deeply. In 1979, when he was in the 9th grade, Ward was attacked by a group of white college-aged kids simply for being in their neighborhood while waiting at the bus stop near his school. “I took a beating,” he wrote in American Educator. “But it was in that moment when I realized that the fight against bigotry is important, that all of us are obligated to draw a moral barrier against hate. I didn’t tolerate bullying among my friends, either. I was always trying to find ways to interrupt and de-escalate.”

Ward’s inclinations toward action and inclusion would be fostered—and tested—by his immersion in the Southern California punk rock scene. Punk music was born kicking and sneering in New York City and London in the mid-1970s and several years later emerged in Los Angeles with bands like X, Black Flag, and The Germs. Characterizing punk, and also hip hop, as “the rebirth of counterculture music in America” that “for a moment shook the status quo,” Ward describes a vibrant milieu that brought kids from disparate economic classes, racial backgrounds and sexual orientations together in unsupervised spaces “before our parents could even understand what to do about it.” It was a raw scene that carried an energy of rebellion. For some kids, that meant not conforming to suburbia. For Ward and other kids of color, it meant “a glimpse at what a multiracial society might be like. And it was really exciting.”

Ward might have been a very different kind of rock star if he’d remained in Southern California. But again, if he’d stayed, he isn’t sure he would have survived.

As his connection to the punk scene was taking root, Ward was simultaneously enrolled in Junior ROTC at school and planning for a future in the military. His sister, who was five years older, had gone through the youth military training program and his father had fought in World War II. “There’s not a generation in my family that hasn’t been in the military in some way,” he says, “at least as far back as the Civil War, as we understand it.” And so, while classmates spent spring breaks skiing or going to Palm Springs, Ward drilled in mini boot camps on Coronado Island or on Navy vessels off the California coast. He notes that while some of his peers were inspired by the idea of fighting in the military by 1980s films like Rambo and Taps, to him it was about service: “That’s how I knew best to serve my country. To serve my community.” Ward joined the Navy after graduating from high school in 1983.

But in the middle of boot camp near the Great Lakes, in humidity he was not accustomed to, Ward started getting headaches and his blood pressure went up. A swift decision was made to give him a medical discharge, the papers for which he refused to sign, even though he knew it wouldn’t make any difference. “I was just in shock,” he recalls. “I had no fallback plan.”

Finding himself back in Southern California, Ward regrouped and found work as a security guard and later at a gas station. He also jumped back into the local music scene, forming a band called Sloppy 2nds with students from Long Beach State. They played punk and ska, and also reggae and new wave. But the scene turned ugly when neo-Nazi skinheads started showing up from nearby suburban Orange County (referred to back then as “behind the Orange Curtain” for its homogeneously conservative, WASP-y makeup compared to Los Angeles County where Ward lived). Not all punk rockers who shaved their heads were neo-Nazis, but those who embraced the symbols and ideology of white power were often violent. Ward remembers a definitive moment at a concert at the Olympic Auditorium in downtown LA in 1985. “It’s a show headlined by the Dead Kennedys, and opening is Fishbone, one of the most amazing punk-ska bands in the United States,” recalls Ward. “Racist skinheads started shouting ‘Sieg Heil’ from the audience, and Fishbone called them out. These Nazi skinheads attacked the stage, and they stabbed the bass player that night.”

This strain of hate, combined with police harassment of punk rockers and a flood of crack cocaine, crystal meth and heroin onto the streets of Southern California led Ward to an epiphany—that if he didn’t get out of Long Beach, he might not live past his 20s. It was 1986, and Ward decided to move to Eugene, Oregon, with several friends who were headed to college there. Incidentally, after he left Long Beach, members of Sloppy 2nds reformed as the band Sublime, which would attain major commercial success in the 1990s. And so, Ward might have been a very different kind of rock star if he’d remained in Southern California. But again, if he’d stayed, he isn’t sure he would have survived.

What Ward found in the Pacific Northwest in the late 1980s was natural beauty, a thriving punk scene and a variety of grassroots coalitions—which he would later learn included right-wing hate groups affiliated with the likes of the White Aryan Resistance (WAR, headed by white supremacist Tom Metzger) and the Idaho-based Aryan Nations. At this point Ward describes himself as cynical, sarcastic and nihilistic, quick to call the world messed up but not doing any analysis as to why it was so. He applied for lots of blue-collar jobs, but no one seemed interested in hiring him. The first person to do so was a rural white conservative who told Ward he’d never met a Black person before. They worked side by side installing insulation in homes, and while Ward realized it wasn’t something he could or wanted to do long-term, he came to see that he and this white conservative shared values and desires common to just about everyone: safety for oneself and one’s family, opportunity, responsibility and caring. However, he says he was still largely naive about the systemic forms of discrimination operating under the surface of “this nice, clean, hippie college town.”

In 1987 Ward enrolled at Lane Community College in Eugene, describing it as a time when, as is the case for many college students, his critical thinking skills were beginning to kick in (the “ability to process the music and the lyrics,” he analogizes). He signed up to do work-study and figured he’d get a job working in the cafeteria, which he’d done in junior high school. Something else he did in junior high was take typing, and it was this skill that instead landed him a job at the campus multicultural center. One day the woman who ran it, Connie Mesquita, asked Ward if he would escort a speaker around campus for a day. The visit had been organized by a group called Clergy and Laity Concerned (a national organization that started as Clergy and Laymen Concerned about Vietnam). The speaker was Dennis Banks, an Ojibwe American who had founded the American Indian Movement in Minnesota in 1968; was involved in the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota; and had eventually served time in prison. Ward didn’t know who he was, but when Mesquita added that she wanted him to go to lunch with Banks, Ward, who was mainly subsisting on Earl Grey tea and Top Ramen, was on board. Then he heard Banks speak. “I’m super intrigued—like, who is this guy who’s so quiet and so assured, right? And then we go to lunch in the cafeteria. We put our trays down and he just looks directly at me and asks, ‘What are you about?’”

“I didn’t have an answer for Dennis Banks,” Ward tells me. He managed to shift the focus to Banks and got through the lunch. “And when I took him to the next class, I thought to myself, if anyone else ever asks me that question, I want to be able to respond.”

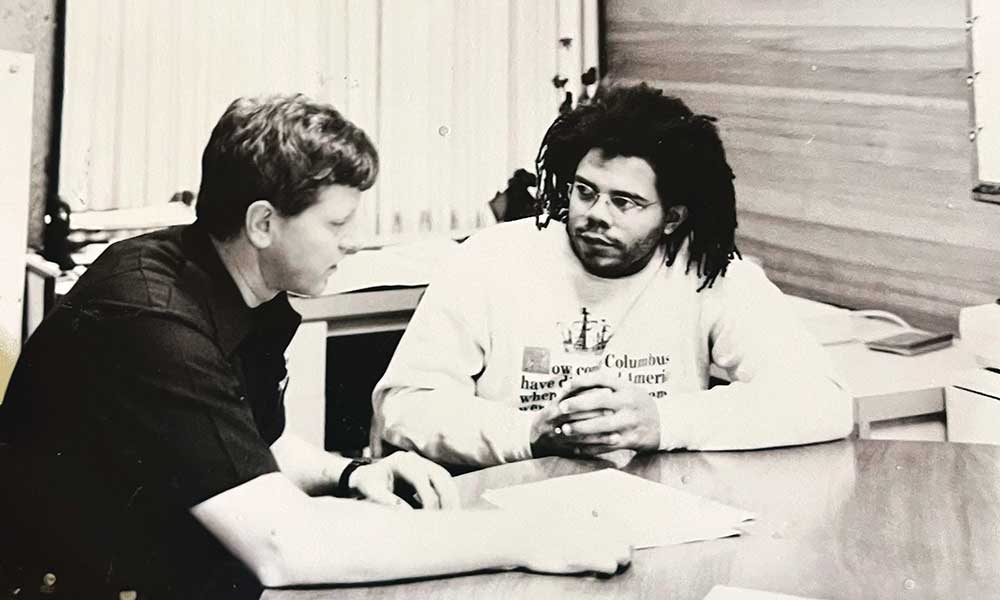

Ward with a board member of the Coalition for Human Dignity, an anti-fascist organization based in Oregon in the late 1980s through the 1990s. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Eric K. Ward)

Ward would eventually transfer to the University of Oregon, where he became codirector of the Black Student Union. In that role, he wanted to bring together all the various student unions to make space for any and all groups facing discrimination. (“Tolerance was really important to me,” Ward says.) This meant meeting with the leaders of the Native American, Asian American and Latino student unions, as well as the African, International, LGBTQ and Jewish student unions.

When Ward sat down with Yonah Bookstein of the Jewish Student Union, he remembers saying something to the effect of “‘You know, we want to take on racism and bigotry on campus,’ and [Bookstein] responded with something like, ‘Do you see antisemitism as a form of bigotry?’” Despite not really knowing anything about antisemitism, Ward’s answer to Bookstein, who today is the rabbi at Pico Shul in Los Angeles, was “Absolutely” (“because I wanted him at the table, right?”). Ward set out immediately to educate himself on the topic. One of the spaces that afforded that education was a feminist bookstore in Eugene called Mother Kali’s Books.

“I would sit on the floor at Mother Kali’s for hours and just read, and no one cared that this guy was sitting in there. I tried to be super small in that space, respecting that it wasn’t my space. But, you know, that bookstore always made me feel like it was my space. And so, I read a lot of feminist books.” One of them was called Yours In Struggle: Three Feminist Perspectives on Racism and Anti-Semitism by Elly Bulkin, Minnie Bruce Pratt and Barbara Smith. It was the essay by Smith, a renowned Black feminist scholar and activist, that Ward remembers most. Today he would criticize it for not focusing enough on antisemitism (“but respectfully; I’m not going head to head with Barbara Smith—I lose that fight”), but to first read about antisemitism through the writing of a radical and respected Black feminist impacted what would become his own ability to connect dots in important and influential ways. The other defining book for Ward during this time was Rabbi Michael Lerner’s The Socialism of Fools: Anti-Semitism on the Left, which he says “explained antisemitism as both a conspiratorial model and a system of biases that wrestled with the question of antisemitism and Zionism.”

Throughout college, Ward’s ties to the punk music scene remained strong. He lived with members of a local Eugene punk band and spent a fair amount of time going to shows in Portland and Seattle. There he observed the infiltration of racist skinheads into the scene, similar to what had happened in Long Beach. Dressed in combat boots and bomber jackets adorned with swastikas, these young, disaffected white punks were being recruited by far-right and white nationalist groups with the narrative that non-whites were to blame for their lack of opportunity and poor economic prospects. Portland especially became dangerous in the late 1980s and 1990s for people of color, for women and for gay people. The 1988 murder of an Ethiopian student named Mulugeta Seraw by three White Aryan Resistance members, who beat him to death with a baseball bat in front of his apartment in Portland—“because of his race,” one stated at his murder trial—was a particularly loud wake-up call.

“Oregon was a place I had come to love, a place that I called home,” Ward recalls. Thinking about his experiences with neo-Nazi skinheads in California, he decided to stay and fight back. He describes the Portland street kids, punk rockers and artists as drawing a hard line in the sand, showing up at venues where they knew racist skinheads would be to defend the subculture that was, for many, the only family they had. “And if that meant physical confrontation, we were going to have physical confrontation,” Ward says, which “spilled out of the music clubs and bars into physical street confrontations, attacks on each other’s residences, arrests, murders, you name it.” It’s a story of resistance Ward talks about in the 2023 documentary short We’ve Been Here Before, directed by Jacob Kornbluth and produced by Reboot Studios. At the same time, it’s not a story he’s willing to tell in full. “Lots of folks were harmed in significant ways, right? And so, some of us don’t feel like we have permission or that it’s safe to tell those things, to restir the pot.”

In 1991, after neo-Nazi threats forced the cancellation of a concert in Eugene by the band Fugazi, Ward founded a group called Communities Against Hate and produced a newsletter called The Race Mixer (tagline: “Miscegenation at its finest!”). He was also hired as an organizer at the Community Alliance of Lane County and at the same time was contacting major Jewish organizations to learn more about antisemitism. He credits Ken Stern—now the director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate who at the time was leading the Division on Antisemitism and Extremism at the American Jewish Committee—for returning his call, spending a good hour on the phone with him and, several weeks later, sending Ward a box full of reports, articles and analysis on antisemitism. Interestingly, Ward says his community work and his involvement in the music scene at this time were distinct. “I had a job doing anti-hate work, but I was part of a subculture as well. And those things didn’t overlap as much as folks think they did.” And yet there was always a common theme: connecting dots to understand and confront hate.

After college, Ward got involved in researching white supremacists at Western States Center (WSC). At the time, the Portland-based social justice nonprofit was putting its resources toward researching and tracking various strains of right-wing populism in the Pacific Northwest and mountain states: anti-gay, anti-abortion, anti-immigrant, anti-environmental.

“We used early databases to assemble a picture of who these right-wingers were,” says Jeff Malachowsky, a longtime philanthropist and social justice activist who founded WSC. In looking into who was funding them, who the organizers were and who attended their meetings, Malachowsky says WSC researchers found that the various groups were often backed and trained by the same people who were building what today are understood as precursors of the Tea Party and the alt-right. Malachowsky recalls first meeting Ward when he came down from Eugene and visited the office. “He was an interesting looking guy; he had dreadlocks and army pants that were cut off into frayed shorts. A big guy with a giant tattoo on his calf and a slow, wandering eye,” says Malachowsky. Ward joined the WSC leadership program and became part of what Malachowsky calls “quite a crew of counter-right-wing researchers and trackers.” This included Scot Nakagawa, later senior partner of ChangeLab, an Asian American-led racial justice laboratory; Tarso Luís Ramos, today executive director of Political Research Associates; and Glenn Harris, president of Race Forward, a bicoastal nonprofit dedicated to advancing racial justice through research, media and leadership training.

Malachowsky recalls being terrified when Ward started to travel and attend right-wing training sessions. “I was directing the show, so I was sending people out and raising the money and reading the reports. But damn, I wouldn’t be going out there in the boondocks and walking into these trainings. Eric was doing that, bringing back reports. We’d put it in the database, and he’d go out again.”

He praises Ward’s commitment as a testament to his courage, as well as to his unique interpersonal skills. “What makes him so extraordinary, effective and appealing as a leader is the specific nature of his gregarious personality. Eric is deeply interested in everyone he meets and engages intently and makes people think they are the sole focus of his attention,” Malachowsky says, adding that many great leaders have this ability. “He’d walk into these meetings, and they’d all be in camouflage with guns, and he’d be in camouflage with dreadlocks. And they’d get along and they’d talk. And they’d welcome him back when he came back.”

In 1994 Ward joined the Seattle-based Northwest Coalition Against Malicious Harassment as a field organizer and began to travel farther and farther out into rural areas. For the next nine years he helped establish or revive some 120 local task forces, in some cases consolidating them, in order to form a regional identity in the fight against white nationalist hate.

Malachowsky remembers Ward diving ever deeper in making the connection between white nationalist ideology and antisemitism. “Eric is someone who is curious enough to learn something, and then, upon learning, makes connections between things that are seemingly unconnected,” says Malachowsky. “His analysis began to resonate as evidence emerged in the larger world and in the press that, in fact, antisemitism was alive and creeping underground like a fire under the forest wall,” he says, giving Ward credit “for insisting within the networks of progressive, liberal and political strategists that we had to pay attention to antisemitism. Not simply as an evil of its own, but as a keystone to understanding this larger and more threatening right-wing ideology that was beginning to travel the globe. I give him a tremendous amount of credit for having that insight and making it stick.”

After years of field work—Ward estimates that between 1994 and 2003 he was on the road half the time—Ward spent eight years in Chicago working with immigrant rights advocates. Then from 2011-2017 he turned his talents to philanthropy and grant-making endeavors, first with the Atlantic Philanthropies and then at the Ford Foundation in New York. Ward says that anyone who is serious about holding leadership positions within social movements should have to spend some time on the philanthropy side, arguing that it breaks you out of groupthink and forces you to defend your positions.

In 2017 he left philanthropy and returned to Portland to take over as executive director of the Western States Center. He was at the group’s helm during the years of the Trump presidency and the coronavirus pandemic, when paramilitary and alt-right violence in the Pacific Northwest and mountain states surged and urban unrest spiked after the murder of George Floyd. Ward lent his expertise on white nationalists, hate-fueled violence and authoritarian movements to the center’s efforts to promote an inclusive, multiracial democracy. In 2022, Ward joined Race Forward as executive vice president.

I ask Ward how his theory that antisemitism underlies anti-Black racism has been received in the Black community. “I’m not here to create hierarchies of oppression around anti-Black racism and antisemitism,” he tells me. “What I’m here to say is that they’re both killing us. They’re killing Black people in Buffalo. They’ve killed Black people in Charleston. Jews have died from antisemitism in Pittsburgh. Latinos have been killed by antisemitism in a Walmart in El Paso. In each of those cases, the killers thought that they were in an existential war with the Jewish community.” Characterizing the Great Replacement theory as the Protocols of the Elders of Zion 2.0, Ward concludes that white nationalists are still “using antisemitism to build their social movement and using this conspiracy theory to drive people toward violence.”

He acknowledges this message can be challenging for people in the Black community, because it’s decentering and seems to undermine Black agency in hard-fought victories of the civil rights era. Also, because American society has categorized race as a Black-inferior/white-superior binary, it can be confusing to hear him say that Jews also face a form of racism called antisemitism. “How can people who mostly appear to be white face racism?” people ask him. “But that’s what antisemitism is,” Ward says. “It is that racialization of Jews in the Iberian Peninsula in the 1400s that eventually becomes European white supremacy or antisemitism, right? The idea of Jews not as a religious or ethnic other, but as a racialized other. And it is that racialized hatred of Jews called antisemitism that leads to things like the Holocaust.”

Ward performing as Bulldog Shadow at Arlene’s on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 2016. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Eric K. Ward)

Perhaps more than anyone, Ward has been successful in getting this message across. “Eric is able to reach diverse audiences and help people recognize antisemitism in themselves, which is extremely special. He’s remarkable in helping minority groups understand the power of standing in solidarity to fight antisemitism and racism,” says Sara Brenner, executive director of the Jewish Community Foundation, which is part of the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington, DC, who has known Ward for years. It’s a form of bridge-building, which he’s undertaken throughout his life and has often involved risk-taking; he has compared it to diving off the stage at a punk show and trusting the crowd will catch you.

At the Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore, Ward shared something folk singer Tom Paxton once taught him in a music class, which was the secret to good songwriting: “It’s not about telling your story but telling your story in a way that allows other people to see themselves in it.” That’s the value that every artist should carry, Ward says. “We don’t need more politics; we need more stories that thread us together. So, the thing we’re gonna do is be excited and be nervous, and we’re not going to know the difference. But we’re going to jump off that stage anyway, together, and if we’re threaded, that’s how we know we’re going to catch one another. Right?”

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

3 thoughts on “The Courage of Eric K. Ward”

I’ve had the privilege of meeting Mr. Ward in Portland last year.

He is so well informed and engaging, I could talk to him for hours, and by talk I mean listen.

Keep up the good work. I trust our paths will cross again in the future, and I look forward to it.

Great article, thank you.

I’m taken aback by the quality, insightfulness and breadth of this piece. You have presented someone I had not heard of but by the end of the article, feel that I know. THANK YOU. Impressive!!