We want to hear from you. To join the conversation, send a letter to editor@momentmag.com.

FROM THE EDITOR

GOLEMS, AI AND ASIMOV

Congratulations on the Summer 2023 issue (“Meet the New Golem. Same as the Old Golem?”) and its fine look into the problems and opportunities surrounding artificial intelligence. I particularly liked what Helen Greiner and Craig Newmark had to say on the “Big Question” (“Is Artificial Intelligence Good for Humanity?”), but then I have always been something of a technology optimist.

The piece that engaged me most was Nadine Epstein’s “From the Editor” (“Learning from Isaac Asimov”). I started reading Asimov as a teenager in the 1950s and always found him fascinating and rigorous. Bottom line—“Meet the New Golem” deserves all the prizes it is sure to win.

Jonathan Friendly

Charlevoix, MI

BIG QUESTION

WHENCE OR WHITHER?

First off, this letter was written by a genuine human being. That said, “Is Artificial Intelligence Good for Humanity?” (Summer 2023) provided this reader with a range of responses from learned men and women, unlike in any other publication I have seen. From the first Tree of Knowledge grasp, unto the Golem and robot, the question is, does “Whence?” really matter, as opposed to “Whither?” Are present—or future—human beings really willing to abdicate their historic role as creators of better futures for humanity and instead program instruments likely to usurp humankind’s own independence?

Bill Younglove

Lakewood, CA

ASK THE RABBIS

KOL HAKAVOD

Thinking about the impact artificial intelligence will have on people’s spiritual lives (“Ask the Rabbis,” Summer 2023), I would first say that, while innovative, this technology will likely reflect back the same issues that already exist in machine learning and adaptive algorithms. We’ve seen the ways in which social media bots reflect back our own prejudices and biases, and it is incumbent upon us to be mindful of the reflections these technologies show. (I want to give kavod here particularly to researchers like Timnit Gebru, who have been raising these concerns since the early days of AI technology.) When establishing a “normative” use case or test example for any AI learning, we must be vigilant to produce an accurate picture of the fullness of humanity, of all those who will be using this technology, and not create a world that reflects and centers only whiteness, maleness and a Christian worldview.

Of particular concern from a workers’ rights and Torah justice perspective is also the mental health and proper compensation of the workers who review and train AI to recognize explicit content.

These individuals spend hours combing through disturbing, illegal and exploitative content. What do we owe these workers, who serve as a bulwark for our own online experiences?

The dual mandates of Jewish spirituality to seek attachment to the Divine and to seek the holy unity lying underneath our everyday temporal encounters are bound up in all these ethical questions. Despite the challenges, I’m excited to see how the Jewish world interacts with AI.

Rabbi Margo Hughes-Robinson

New York, NY

PERPETUATING STEREOTYPES

As a longtime contributor to “Ask the Rabbis,” I am always curious to see the image that accompanies our diverse responses to the question. Often these images are a representation of the question and invite further musing. I was frustrated by the image that accompanied the most recent column about the impact of AI on people’s spiritual lives. The rabbi pictured is obviously male and traditional—one might even say ultra-Orthodox given the clothes and beard—and does not reflect the diversity of voices the column invites. In this issue alone, four of the rabbi respondents are women.

The offending image was created by an AI image generator. Notice here that the algorithm perpetuates stereotypes and outdated assumptions about who is a rabbi and does not reflect the diversity of identities we see in today’s rabbinate.

I very much appreciate that “Ask the Rabbis” contributes to efforts at changing narratives about who is a rabbi. The editors of Moment magazine, especially the column’s editor Amy E. Schwartz, understand and value that. This is not yet true of AI and thus highlights one of the dangers of relying upon it.

Rabbi Dr. Laura Novak Winer

Fresno, CA

CHEFGPT

STRANGE, UNAPPETIZING FOOD

I was amused by the recent “Talk of the Table” (“A Chat with ChefGPT” Summer 2023) that asked ChatGPT for recipes. As the AI openly admits, it has no “preferences or taste.” ChatGPT is also not infallible, as noted in a recent Wall Street Journal newsletter noting that AI chatbots “may produce odd results like strange recipes, unappetizing food combinations and nutrition information that is outdated or not accurate. Users should take the recipes with a grain of salt…especially if it suggests meals with ingredients that could be detrimental to one’s health.”

Maple bacon challah is obviously unacceptable, and ChatGPT has no context for what matzah ball soup should be. It should not have coconut milk or curry. And speaking personally, cilantro and cayenne pepper are how you ruin good food. I think I’ll stick to my own cookbooks and life experience.

Susanna Levin

New Rochelle, NY

BOOK BANS

DON’T BE AFRAID, VOTE!

We just received our first issue of Moment magazine. While it is full of incredibly informative and timely articles, the one that stands out for me is “Fear and Loathing in the Library” (Summer 2023). Sarah Posner does a remarkable job outlining not just the conspiratorial actions of a few, but also the relationship of book banning to other anti-“woke” actions of local, county and state officials. Whether it be from school boards, city councils, state legislatures or governors, there is a well-funded and well-organized conspiracy to change and deny historical fact, alter public perception and create unjustified fear of anyone who doesn’t look or act like the book ban perpetrators.

This is why I consider local and state elections more important than federal elections. While Congress and the president have significant power to wield, our own lives are impacted each and every day by the laws and regulations enacted by our local municipalities and states—from moves to restrict reproductive care to the efforts to ban drag shows, Black history and gay rights.

If you want to stop the loathing and fear in our libraries, take a stand. Vote in elections at all levels.

Jeffrey Paul

Albuquerque, NM

THE LEFT CENSORS TOO

I share Sarah Posner’s allergy to censorship. For those who care about American values, there’s something deeply troubling about the idea that freedom of expression might be curtailed in the service of a political agenda. No less troubling from a Jewish perspective, history is littered with pages of Jewish texts expurgated or censored by religious or political authorities.

But why should the left’s proclivity for book-banning be any less objectionable than the right’s? To Kill a Mockingbird has been removed from numerous school curricula for portraying racism, and Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced in 2021 that it would stop publishing six of the author’s works because they “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.” When school boards decide that a book might be offensive to a given minority, why do they get a pass? When retailers make certain books unavailable because they consider them out of step with the zeitgeist, why is there any less outrage? When opponents of censorship pick and choose the targets of their opprobrium, they risk becoming party to the very offense they claim to oppose.

Rabbi Yosie Levine

New York, NY

ECHOES OF APARTHEID

I grew up under apartheid in South Africa, where the government censorship board banned or severely restricted thousands of works, including the most harmless children’s stories (Anna Sewell’s 1877 book about a horse, Black Beauty, was briefly banned because of the title).

At university, to read basic political texts such as Marx’s Das Kapital, we had to show ID and read in a locked room with barred windows. Books were banned not just for discussing racial justice or class equality (these apparently “inflamed hatred”) but for any reference to “degenerate” or “immoral” practices (writing about sex or sexuality, namely homosexuality and interracial relationships, were both crimes under apartheid).

It’s been chilling seeing so many U.S. states stamping out debate and criminalizing the exchange of facts and ideas. South African activists had secret hiding places in which to stow our banned books, and the notion that American librarians and citizens may have to do the same in 2023 is one more thing that makes the rise of apartheid-style authoritarianism in the United States look both insane and immoral to the rest of the world.

Helen Moffett

Cape Town, South Africa

MOMENT DEBATE

DOING A CLIMATE MITZVAH

While Saul Elbein and Mona Charen both make good points in the “Moment Debate” (“Is changing our personal behavior key to saving the planet?” Summer 2023), both miss the depth of the change that is going to be necessary to deal with climate change. Judaism and other spiritual traditions play an important role in forming essential ideas of our place in the world, and they turn out to be consistent with modern systems approaches that emphasize relationships and realize that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Unlike the old mechanistic, reductionist science, systems science (and traditional wisdom like Judaism) better demonstrates how things actually work in the world.

We are constantly being caught off guard by the way that nonlinear change happens in regard to climate. Our models keep missing the quick jumps that the climate system can take when a small change triggers a positive feedback loop. In the same way, one of our small actions can sometimes go viral and change the world—especially now that our small actions can be posted on social media and influence thousands of people. In a complex system like our planet, we are all interrelated and even small actions make a difference. That is the idea not just behind the story of planting the carob tree (which, by the way, was Honi the Circle Maker, not Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai) but the whole system of “doing a mitzvah.”

A mitzvah can be understood as a small action you take because it’s the right thing to do—and it just might change the world. As important as technical solutions are, we must shift to a culture that recognizes the sacredness of the beautiful whole, the planet and the cosmos, of which we are a part.

Rabbi Natan Margalit

Newtonville, MA

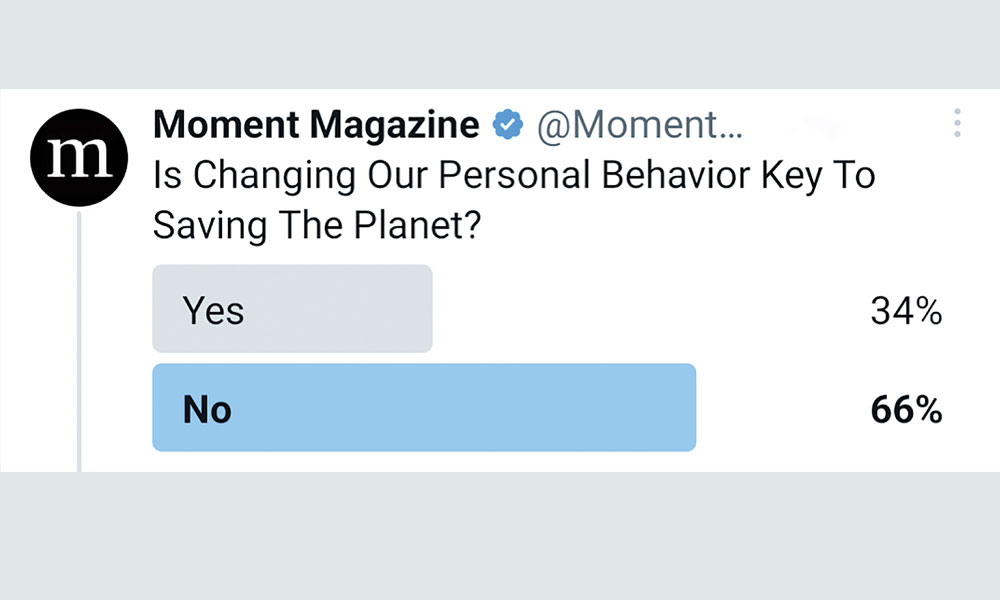

MOMENT DEBATE POLL

In the summer issue of Moment, we asked followers of the magazine’s X (formerly Twitter) account if changing personal behavior was key to saving the planet. The majority answered no.

Read the debate at here

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.