From the first bonfire of the vanities in Florence in 1497 and even farther back to ancient times, books and other written material that have elicited in readers various feelings—excitement, fear, inspiration, doubt, rebellion—have been suppressed by censors for whom such human expressions pose a danger, most often to their own power or sense of propriety. In the United States today, bans and challenges to books deemed problematic are on the rise and come from myriad directions.

A banned book may be a work of fiction or nonfiction, it could even be a picture book, that has been removed from a course or taken off the shelves of a library or bookstore “because someone considers it harmful or dangerous,” says Emily Drabinski, the head of the American Library Association. A book that has been challenged, with the intent to ban, may be removed pending review, and sometimes a challenged book is moved within a library or store with the intention of making it harder to find. In trying to understand and thwart such efforts, it’s crucial to understand all that these books offer. And while it can be exciting to approach a list of banned books as reading recommendations—after all, there must be something good in them if they get people so riled up!—the truth is that the more books are censored, the less chance they have of impacting or even transforming lives.

And so, we asked a few prominent writers and readers to share a story about a banned book that had a significant effect on their life: a book that was important to them at a pivotal period, maybe one that changed their thinking or set them on a particular path. And we asked them to consider what we collectively lose if or when that book disappears from the shelf.

SHERMAN ALEXIE ON OF MICE AND MEN BY JOHN STEINBECK

ROBERT ALTER ON LOLITA BY VLADIMIR NABOKOV

DREW GILPIN FAUST ON THE DIARY OF A YOUNG GIRL BY ANNE FRANK

LINDA MANNHEIM ON MAUS BY ART SPIEGELMAN

RUBY NAMDAR ON THE TALMUD

PAMELA PAUL ON 1984 BY GEORGE ORWELL + A CLOCKWORK ORANGE BY ANTHONY BURGESS

JUDITH SHULEVITZ & JO LEMANN ON BELOVED BY TONI MORRISON

Editor:

Jennifer Bardi

Interviews:

Jennifer Bardi, Diane M. Bolz & Amy E. Schwartz

Drew Gilpin Faust. (Photo credit: Courtesy of Drew Gilpin Faust)

DREW GILPIN FAUST

I grew up in Virginia in the 1950s, when Virginia was pretty rigidly segregated. Even my household was rigidly segregated, with African-American workers who cooked, cleaned and did the yard work and who were confined to one part of the house and designated to use one particular bathroom, which the rest of us were not supposed to approach.

So that was a world I came to recognize as unjust at a pretty early age. It was also a world in which gender prescriptions were very sharp. My mother often said to me, “It’s a man’s world, sweetie, and the sooner you learn that the better off you’ll be.” None of my mother’s friends worked outside the home. I didn’t know a lady doctor or lawyer, or a woman who had a professional life. And so, if I looked for role models, it had to be through books.

Books had an enormous impact on me, as did the emerging civil rights movement and the response to Brown v. Board of Education by white Virginia leaders who imposed massive resistance to integration. I was infused with a sense of justice and courage, and how important those were in a variety of realms, and also an eagerness to find in literature what I wasn’t able to find at home.

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank (commonly called The Diary of Anne Frank) was a book that answered many of these needs for me, in that here was a young woman who was a writer already determined to have a life that was more meaningful than just that of a housewife. That seemed very resonant to me. She was also seen, as she thought, anyway, as the disfavored child, the one who was difficult. I always felt I was that child because I didn’t want to succumb to the gender expectations that were part of my mother’s specific expectations of me.

“I get so frightened when I think about this kind of banning of books, because books were my pathway out of the world in which I was raised. A matter of survival.”

I acquired Anne Frank almost by accident, in a bookstore in New York while visiting my grandparents. I think I picked it up because that particular edition, which I still have, said on the cover that it was “an extraordinary story of adolescence.” I later learned that this was an effort on the part of the publishers to make Anne Frank’s story a very broad one for young people, not just a Holocaust story. Of course, there’s been a lot of controversy about how Anne Frank has been presented. Is she just a young girl? Or is this a story about the oppression of a Jewish person? Should the Holocaust part be front and center?

I don’t think I’d ever met a Jewish person when I started reading this book. I’m not sure I knew very much at all about the Holocaust, but it was a powerful awakening for me to see both a part of World War II that I had not heard about from my father, who served in the war, and also to see this young girl so threatened by a different kind of injustice—not the racial injustice or the gender injustice that was a central dimension of my life in Virginia but injustice perpetrated against the Jews, and embodied in the life of a young girl.

Something that I came to realize was that young people were heroes in the civil rights era and that a lot of the answers to the questions I was asking were embodied in them. They were the ones integrating the schools. They were the ones in the community next to mine, where the schools did close, who tried to go back to the school and insist that public education ought to be available on an integrated basis. They were the Ruby Bridges. They were the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—SNCC—activists. Anne Frank was another example of a young person acting heroically.

I was struck by her courage, and that in the face of the basic threat to her life, to her family’s life, as well as the removal of what gave her joy in life, she turned inwards to find other resources. That was so inspiring—to think of her resilience in dealing with circumstances that were to me, as a young person, unimaginable. She became an inspiration in no small part because she did it through writing, and I was so interested in words and writing.

Her legacy is one of the written word, and her courage was embodied in those words, which were reflective both of an ordinary adolescent but were also specific to a time and place, with the notion of World War II as a kind of moral emergency, that gave them a poignancy and a force in my mind. I was deeply moved by that.

In terms of The Diary of a Young Girl being banned, I’m guessing it’s because Anne Frank begins to explore her feelings of sexuality with Peter, and that’s been deemed offensive. I get so frightened when I think about this kind of banning of books, because books were my pathway out of the world in which I was raised. A matter of survival. Maybe that’s why people want to ban them, because you’re not supposed to produce children who ask questions, who challenge their parents, who take different routes through life. I don’t know what happens to all the young people who can’t find those paths, for whom they are denied and closed.

Drew Gilpin Faust is a historian and author who served as the president of Harvard University from 2007 to 2018. Her most recent book is her memoir, Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury.

Pamela Paul (Photo credit: Celeste Sloman for The New York Times)

PAMELA PAUL

I originally came across George Orwell’s 1984 when it was assigned to me in a combination social studies/English class in seventh grade—in 1984. I have to commend my teacher for assigning the book, which was probably considered a somewhat risky choice to give to 12- and 13-year-olds.

One of the reasons it has been banned over the years is because of a sex scene, but during that period of heightened Cold War tensions, with Ronald Reagan in office, its anti-fascist, anti-totalitarian warnings were suspected of conveying a sort of communist message.

I instantly responded to 1984. I had never read anything like it—had never read a dystopian novel. And then around that same time, my father, a huge Stanley Kubrick fan, was watching Kubrick’s film A Clockwork Orange. He intimated that maybe I wasn’t quite old enough to see it, but I ended up watching it anyway, and it was shocking to me. There’s an extremely graphic rape scene with full nudity and violence. I had never seen anything like that. I ended up watching the film repeatedly, not because of that scene but because the entire thing is a very dark, satirical look at human nature and efforts by the state to respond to human violence. And it’s also about the fear of what the next generation is going to do. The violence is even more explicit in the novel from which the movie is adapted, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange, which is the second banned book that had a big impact on me. Of course, it was the violence that got it banned and also fears about copycat crimes—that it glamorized violence in such a way that it would inspire young people to be violent themselves.

“If you deprive kids of the ability to think critically about books that present complicated themes, they’re going to lose interest and seek that kind of storytelling or information elsewhere.”

Both 1984 and A Clockwork Orange were about the efforts authorities make to crack down on human independence and individualism. That’s an extremely frightening prospect for a teenager, because you’re just developing who you are and asserting yourself. So, I was really taken with both books and with dystopian fiction generally. It was really the first time I saw the subjects of sex and violence used with the intent not to indulge or moralize but to criticize and satirize, to make a political argument.

I’ll add that a fun aspect of Burgess’s book, if I can use that word to describe A Clockwork Orange, is the language he invented called Nadsat, which is a mix of Russian words and cockney slang.

There’s also a glossary, and so for a certain kind of kid, this secret language is a real draw. It’s like learning a whole new version of bad words. I know that sounds lighthearted, but kids should enjoy books. Yes, these are dark stories, but kids are drawn to dark stories, and A Clockwork Orange and 1984 are both very accessible and readable.

In banning these books, people really underestimate children’s capacity to metabolize difficult scenes or themes when they are used in the interest of an argument or a greater theme. Efforts to “protect” them are so misguided, and educators—really, the culture—has it backwards in saying that if a child is hurt or upset by a book, then it is to be avoided. The exact opposite is true: Literature is meant to provoke. It’s meant to cause feelings. If you strip literature of that power, if you deprive kids of the ability to think critically about books that present complicated themes, they’re going to lose interest and seek that kind of storytelling or information elsewhere. Which, again, is a real loss, because a book is the greatest vehicle for storytelling.

Authorial intent matters here too—what the authors are creating, how they want readers, or expect readers, to respond to their books, to shape a more sophisticated political viewpoint or outlook on human nature.

There’s also a move now to ban books that might include language that people find offensive according to the mores of the day—whether it’s racist or sexist or homophobic language, usually not on the part of the author. Rather, it’s contextualized as aspects of characters in a story. If you give children the opportunity, and if you teach them to love reading and to read critically, they are capable of understanding this. A child can pick up a book like Tarzan of the Apes, which is an abjectly racist book, and not only can they recognize that racism and be offended by it, they should be.

They should understand what racism is. Otherwise, how can they understand progress? You cannot know progress unless you know what we came from and how (and why) we have moved on. It’s simply not enough to tell kids that a book is offensive, but we’re not going to show you why. They need to read it and try to understand how it makes them feel. Whether it’s Huckleberry Finn because it has the n-word, or something else, I really resist the idea that libraries are removing books from their collections that were published earlier than, say, 2008, because they feel the views represented in those books don’t live up to current ethical standards.

Wouldn’t you rather have kids read about difficult subjects in the context of a novel that has been edited with care and published for a young audience? A book they can discuss with a parent, a teacher or friend? The whole idea of policing should disappear when the book is opened.

Pamela Paul is a New York Times columnist and former editor of The New York Times Book Review. Her books include 100 Things We’ve Lost to the Internet, How to Raise a Reader and Pornified.

Linda Mannheim (Photo credit: Tim Mansel)

LINDA MANNHEIM

When a school board in Tennessee voted to remove Art Spiegelman’s Maus from schools in January 2022, my first reaction was: What? The book that changed narratives about Holocaust survivors, gave voice to the descendants of survivors and showed the world why we needed a new genre of literature—the graphic novel—was going to be banned?

The school board’s stated reason for banning the book seemed absurd. But almost all stated reasons for banning a book are absurd, of course. In this case, the board members complained about “a naked picture” in one panel—a tiny, somewhat oblique drawing of Spiegelman’s mother’s body after her suicide.

Soon after news of the ban broke, I wrote in The Nation: “It is impossible for me to imagine what my life would have been like, or who I would be, if I had not read Maus.”

There are many books that are important to me, but no others that are so central to my sense of who I am and how I see the world.

“Book bans erase the possibilities we have for seeing and understanding ourselves and the people around us.”

Maus came to me when I was struggling with my own family’s legacy, and in particular my father’s account of his childhood in Nazi Germany and his years as a refugee. The people who listened to my father’s story—which is to say nearly everyone he met—asked naïve and intrusive questions. And when I looked for other narratives about survivors, the stories I found depicted them as devastated victims or unbreakable heroes. They seemed to exist outside of the world where the rest of us lived.

I was in the living room of a shared student house in Western Massachusetts when I first heard about Maus. Someone was delivering a review of it on public radio and explaining that Art Spiegelman had written about his father, a survivor of Auschwitz. I remember the reviewer expressing amazement that Maus wasn’t about a victim or a hero but about a flawed, ordinary man who had survived. And, the reviewer added, it was grappling with the complicated relationship between the author and his father. The father—racist, difficult, and often insensitive—was like so many other fathers in the borough of Queens. Which is to say, Spiegelman placed his father’s story exactly where it belonged: among all of us.

Needless to say, I ran out and bought a copy, because it felt like this was the book I had been waiting for. And after that, Maus became the book I turned to again and again, especially when I felt like I needed some reassurance.

That might sound like an odd thing to say about a book focused on the Holocaust, but there is something so powerful about Spiegelman’s extraordinary honesty and disclosure as he tells the story.

The difficulties he has with how to tell it are a part of this. We see him talking to his wife Françoise Mouly about how hard it is to maintain the metaphor of depicting Jews as mice and Germans as cats. We witness a therapy session where he talks about the emotional impact of trying to render his father’s story. We see Art at his drawing table, a pile of cartoon mouse bodies surrounding him.

And in the mix, there are also moments of humor, which you need in an honest narrative about death.

When Maus was first published, the most ubiquitous narratives about the Holocaust were what Spiegelman termed Holo-kitsch—cloying sentimental narratives. In the miniseries Holocaust, the characters appear as they would in any soap opera, which is to say as stock figures with simplistic story lines. In Schindler’s List, the hero is a Nazi collaborator who recognizes the error of his ways, and the actual victims are, literally, in the background. But Maus—Maus broke that mold. The audacity of Maus—telling a survivors’ story in a genre that was considered “low culture” and yet offered a richer and more complex depiction than any of these films—shattered the late-20th-century conventions of Holocaust narratives.

One of Spiegelman’s memorable exchanges about Maus was with a German reporter in 1987. “Don’t you think that a comic book about Auschwitz is in bad taste?” the reporter asked, to which Spiegelman replied, “No, I thought Auschwitz was in bad taste.”

Without Maus, it is hard to imagine the genres of graphic literature that came after, both memoir and journalism: Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, Joe Sacco’s Palestine. There are things you can depict in comics that you can’t show on film or in photographs, Sacco has pointed out. “Drawing somehow allows you to look,” he said in a piece published at the website It’s Nice That. “There’s enough of an unreality to it that you can look at things that, if you saw them in an image which purports to be real, you’d feel a need to turn away.”

What book bans do is erase possibilities. They erase the possibilities we have for seeing and understanding ourselves and the people around us.

Linda Mannheim’s most recent book, This Way to Departures, was shortlisted for the Edge Hill Prize, the UK’s literary prize for short story collections. Her work has appeared in The Nation, Granta and 3:AM Magazine.

Sherman Alexie (Photo credit: Fallsapart Productions)

SHERMAN ALEXIE

Of Mice and Men was a revelation for me. John Steinbeck was the first author I ever read who captures rural poverty in a way that I recognized. And, on a far more difficult level, Of Mice and Men captures the violence and ostracism that I experienced during my childhood.

I came across it in the reservation school library and liked the title. I was 12, I believe, and had just begun contemplating leaving the reservation school for the white farm town school. I did make that move. I was an Indian boy who recognized himself in white folks. That’s a huge cross-cultural moment. But it also showed me parts of the world that I knew nothing about. So the familiarity and mystery were simultaneously powerful.

“People are afraid of fiction that feels like fact.”

Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men also served as the gateway to other challenging novels. It was the first “classic” novel I ever read. I quickly read other Steinbeck books, and that led me to Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Faulkner.

Of Mice and Men has been challenged for many reasons, all of them having to do with the honest depiction of humans. I think bannings are mostly motivated by novels that explore human weakness and flaws. People are afraid of fiction that feels like fact.

If the book becomes harder to get and read, we lose the story of white rural poverty in the early 20th century, a huge and continuing part of our culture.

Sherman Alexie is a poet, short story writer, novelist, essayist, memoirist and filmmaker. His book, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian (2007), won a National Book Award and was listed by the American Library Association as the Most Banned and Challenged Book from 2010 to 2019.

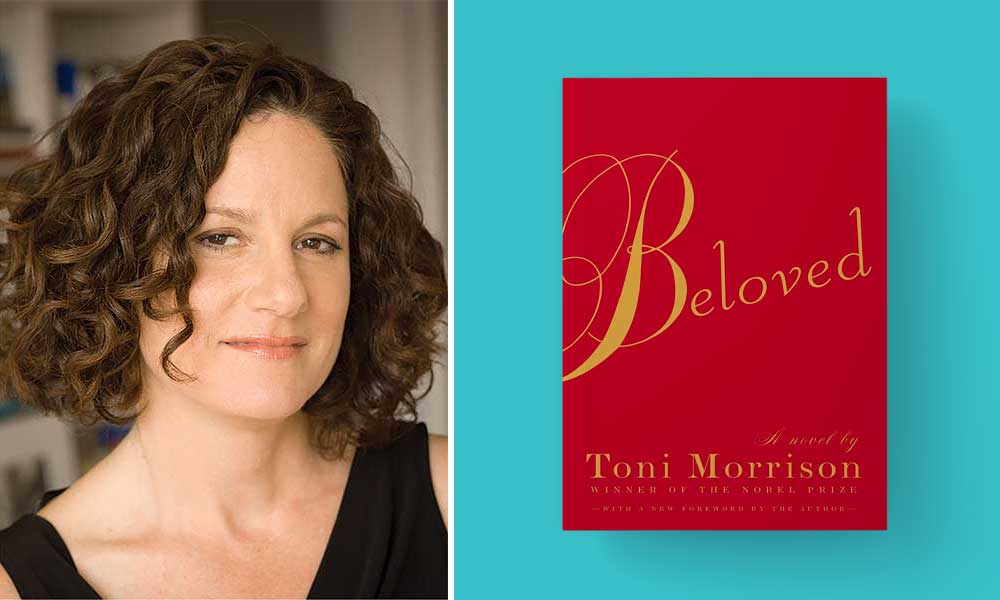

Judith Shulevitz (Photo credit: Courtesy of Judith Shulevitz)

JUDITH SHULEVITZ & JO LEMANN

Judith: When I first considered this question, I was going through the American Library Association’s list of the 100 most frequently banned books (from 2010-2019), and I was thinking that I liked many of them but that none had actually changed my life. Then I came across Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which I knew had changed my daughter Jo’s life. And I knew that I was part of that, not only because we talked about the book but also in the sense that reading together had always been a big part of our lives. (In fact, I used to say to my children—who, I hope, understood it as a joke—that I really only had them as an excuse to reread the books of my childhood.)

Jo was a math girl and then eventually she became a politics girl and probably would have gone into some STEM field or political science. But I watched her get unbelievably excited about this book and take her reading to a new depth.

Jo: I didn’t read Beloved until my senior year of high school, but I feel like the story of my experience with it started in my sophomore year. I had an unusually strict English teacher, who taught in a roundtable style and every day would draw a little map of where everyone was sitting. Students would call on each other, and he would draw a line to show every single pass between a person in the conversation, and he would take notes, marking each time you demonstrated one of his stated elements of good class discussion. And then he would compile statistics on you; participation was a big part of your grade, along with the annotations we were supposed to make in the books we read. It was very formulaic, but I learned a lot, and in my senior year I decided to take his class on magical realism.

I think Beloved was the second book we read. It’s hard to describe, but it felt like something clicked in my brain, like everything my teacher had been trying to get me to understand finally fell into place. With math, I’d always liked the puzzle aspect of it, like you had this thing that seemed so incomprehensible at first, and then you could apply formulas and make it all fall into place. This felt kind of impossible with reading and English class. You’re often told not to worry about authorial intent, and I think when you’re young, that can feel like anything goes. Having some rules made me understand that there were more productive ways to read a text and work toward extracting something valuable from it.

At the same time, it felt like every paragraph of Beloved brought up such strong emotion, and it was hard to understand why this book was so much more meaningful to me than basically anything I’d ever read before. I would come to class and have a lot to say. I would have a lot of quotes to read. I would have questions I wanted answered. I remember telling my mom, you have to read this book because I need to talk to you about it. There was one passage I remember where the grandmother character is giving a sort of a sermon and she says: “In this here place, we flesh; flesh that weeps, laughs; flesh that dances on bare feet in grass. Love it. Love it hard. Yonder they do not love your flesh.” That was the one I most remember reading to you, mom.

“I don’t think you should be banning a book that is telling a truth about the world that is important to American history and important for people to understand.”

Judith: Speaking of problem-solving, the character who calls herself Beloved is a mystery. Where does she come from? Is she real? Is she the ghost of Sethe’s dead baby? Jo, I remember you figuring out that Beloved has memories of things she couldn’t have experienced, concrete and detailed memories too far back in the past, for example of being on a slave ship. I remember when you had that revelation, it was a big “aha!” moment.

Jo: Toni Morrison does such a great job of capturing feelings of love and desperation and loss. Early on, there’s a scene where Sethe (a formerly enslaved woman and the main character) has revealed this sort of tree of scars on her back to the character Paul D, who had been in her life in the past and has now returned as a kind of love interest. He’s seeing these scars on her back, and at the same time he’s holding her breasts. It’s like he’s relieving her in that moment of her duties, trying to take some of that burden. While this and other aspects of the characters’ lives weren’t relevant to my experience in the world, as a high school student on the verge of becoming a woman, the idea of having someone look at the most vulnerable and the most painful part of you was powerful. The emotional truths come through in strange ways in Beloved, ways that feel a little odd when you say them out loud, but in the context of the book, they feel so beautiful. It was something I could have never thought of in a million years, but somehow, I understood it.

I went on to Harvard and took a Great Books course my freshman year after seeing that Beloved was on the syllabus. I joined the literary magazine and committed myself to the world of humanities, of reading and discussing the things I was reading with other people. When it came time to declare a major, I had a conversation with my mom, and she asked me, what do you want to be doing every single day? What do you want your homework to be? And so, I chose History and Literature (a specific concentration at Harvard).

As far as banning Beloved, I want to first note that it’s inspired by a true story of infanticide by a formerly enslaved woman. I don’t think you should be banning a book that is telling a truth about the world that is important to American history and important for people to understand. It’s important to tell it in a novel and not just in a history book, because when you read it in a history book, it’s concrete, but it doesn’t feel real. Paul D is described as having a tin box around his heart, which the character Beloved is, in a way, able to pry open. A history book isn’t going to say that there’s a tin box around someone’s heart because of the trauma they experienced.

A lot of the books that get banned deal with incredibly difficult, sensitive and contentious topics, but they also garner a lot of attention because they elicit powerful responses from readers. That can be a bit scary, but it makes your life so much fuller to be able to read these kinds of books and have these intense experiences.

Judith Shulevitz is a contributing writer to The Atlantic and the author of The Sabbath World: Glimpses of a Different Order of Time. Jo Lemann is a junior at Harvard University, a fiction editor for The Harvard Advocate and a staff writer for The Harvard Crimson.

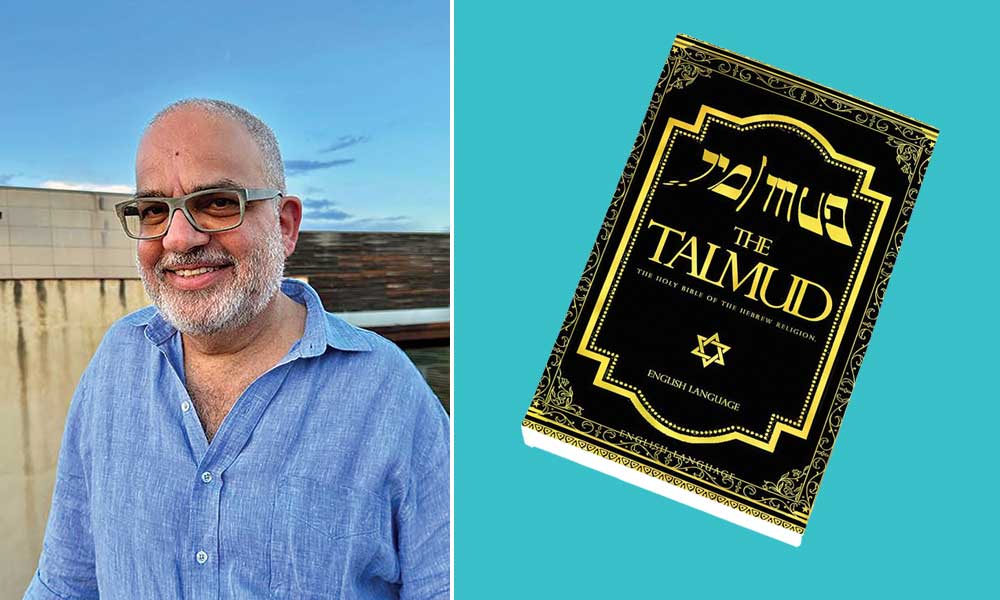

Ruby Namdar (Photo credit: Helen Cohen)

RUBY NAMDAR

My banned book is not really a book, and it wasn’t exactly banned. It is a grand composition that was produced by many authors and scholars over a few centuries, an entire library, condensed into 63 tractates that discuss all things divine and human, mixing together theological and legalistic debates with some wonderfully inventive narrative and peppering this mixture with many moments of wild, irreverent humor. It is called the Talmud. The Talmud had many enemies throughout the generations: Religious sects and churches tried to destroy and delegitimize it, they burnt it in public and slandered it in many vile ways—and yet, it prevailed as the primary source of traditional Jewish learning to this day.

But there was another effort to make the Talmud disappear that was more subtle and interesting, the effort made by the secular Zionist movement to bypass the Talmud and return to the Bible as the main source of modern Jewish learning and identity. Many of the founding fathers of modern secular Zionism were personally well-versed in the Talmud or at least had some acquaintance with it. For them, it was associated with the diaspora, and in order to recreate Judaism and Jewishness as a modern, territory-based nationality, their choice was to push it aside, to place it on a dusty old bookshelf in a back room and say, “That’s for the religious. Let them study Talmud. We are going to study the Bible. Instead of stories about sages and absurd legalistic debates about what happens if an egg was laid on the second day of a holiday and so forth, we are going to go back to the epic, sun-baked, violent, heroic poetics of the Bible. We are going to study about warriors and generals, prophets and kings. We are going to celebrate the ancient roots of the Jewish civilization, and knock through the scholarly, overly intellectual, neurotic world of the rabbis that mediated the Bible to us over the years.”

“While we knew that there was another ‘big book’ named the Talmud, we had never seen it, and had no idea what was happening inside it.”

The way we studied the Bible in the secular Israeli educational system was very different from the way our ancestors studied it. It was stripped of the halo of commentary that surrounded it traditionally and through which Jews have read it over the generations. Taking your Bible “neat” (like a good whiskey) is very different from reading it through the eyes of the rabbis. It was easy to fall in love with the rich Hebrew, the sweeping poetics, and the characters that dripped with vitality and eros. Learning the Bible this way formed me as a man and as an author, infusing my existence with its boldness and magic. I am forever grateful for this rare cultural opportunity.

However, while we knew that there was another “big book” named the Talmud, we had never seen it, and had no idea what was happening inside it. For us, the Talmud was something that only very religious old people studied, something that belonged to the past. This was a subtle way of banning the book. There were no decrees. The Israeli ministry of education did not burn the Talmud to the harsh sound of beating drums, but it was made to be forgotten. It was pushed into oblivion.

There are many ways to approach the Talmud. I personally am drawn to the Aggadah, the narrative part of the Talmud. I am not personally drawn to halacha—the religious law for which the Talmud is famous—and its analytical debate. I am a connoisseur of masterful and artful storytelling, of wonderful imagery. The Talmud serves me these intellectual delicacies in abundance. I must confess that like so many of my other vices and addictions, the Talmud was an acquired taste. Talmudic storytelling technique is very different from that of modern literature and even the Bible.

The biblical tale is like a large canvas, painted with intense, thick oils. The Talmudic tale is often drawn like a short, opaque riddle. It is a narrative essence that the reader needs to work hard to “open.” It is not displayed on a huge screen like an old Cecil B. DeMille production or sung in your ear like an operatic, epic tale. The drama of the Talmud is more like a chamber drama, more intellectual, less sensual and at times quite convoluted and even subversive. But the more I delved into the wonderful world of Talmudic narrative, the more I fell in love with it.

To do so, I had to discover it and “un-ban” it—bring it back onto my bookshelf and into my world of association. I am, of course, not alone in this quest. It was a generational task, and I owe great gratitude to wonderful teachers—like my dear friend Dr. Ruth Calderon, for example, who was one of the founding mothers of this movement and led the way to the exciting rediscovery of the Talmud by secular Israeli intellectuals, artists and authors. Our task is the reappropriating of the Talmud, taking it back from that dark corner to which it was banished, putting it on the table and reading it, not necessarily the way it was taught in the Yeshiva world over generations, but as our ancient literature, a collective treasure box of meaning, poetics and imagery. I’m very proud and delighted to be one of the people unearthing this treasure and opening it for others through my teaching and writing. I do it in a way that’s unorthodox and may seem irreverent, but I do it with great love and respect.

Ruby Namdar is an Israeli-American author. His novel The Ruined House won the 2014 Sapir Prize, Israel’s leading literary award. He currently lives in New York City, where he teaches Jewish literature, focusing on biblical and Talmudic narrative.

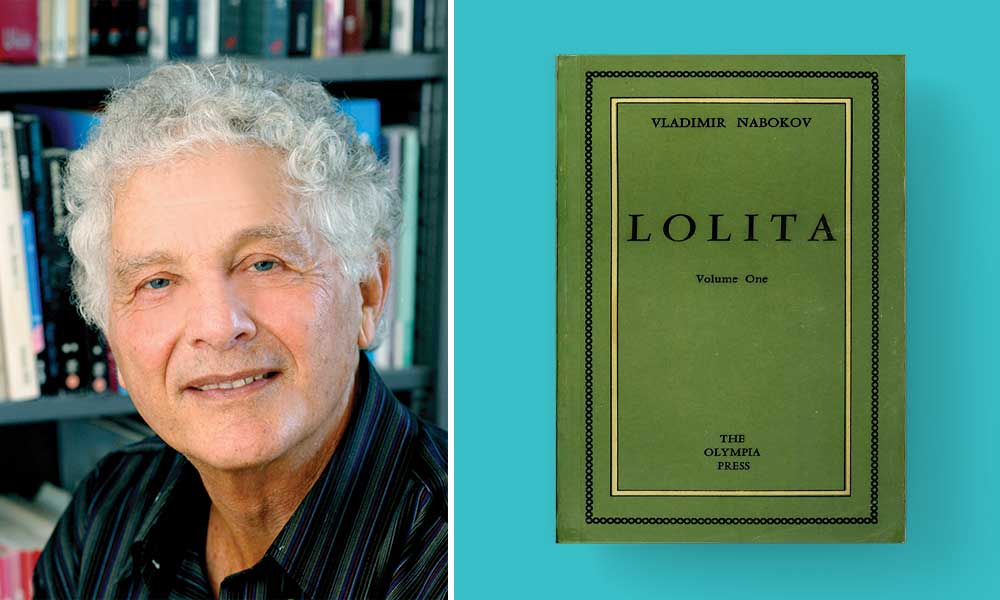

Robert Alter (Photo credit: Courtesy of Robert Alter)

ROBERT ALTER

When Vladimir Nabokov finished the manuscript of Lolita, his friend, the critic Edmund Wilson, who himself had published a volume of short stories with a lot of explicit sex in them, was dismayed and advised Nabokov not to publish it. It went the rounds of a few trade publishers in this country, and nobody wanted to touch it. So its very first publication was with one of those Parisian publishing houses that sell books in brown paper wrappers.

The main character of Lolita, Humbert Humbert, is a man in his forties who has a sexual fixation on prepubescent girls. He lays eyes on Dolores Haze (whom he calls “Lolita”) when he comes to look at a room her mother is renting. He sees Lolita in a bathing suit out by the family pool and is totally smitten with her. Later on, the mother is conveniently run over by a car, and Humbert drives to Lolita’s summer camp and says he’s her father. He takes her to a hotel and has sex with her and then the two start on a long cross-country drive, staying in one motel after another.

Nabokov loved America when he came here as an exile from Russia, and he evokes all the local settings, the motels, the gas stations, the 7-Elevens and so on, and all along the narrator is having sex with this 12-year-old. That’s what’s shocking, and all the more so because it’s told from the narrator’s own perspective.

“The novel is a probing and even moving representation of a man who is trapped in his own obsession, causing great harm and unable to break free of it.”

In many of his novels, not all of them, Nabokov was interested in twisted people, people who showed some sort of psychological perversion or aberration. Humbert’s is the most extreme, and of course many other great works of fiction deal with perverse people. The point is, and it was reinforced in interviews during Nabokov’s lifetime, that all along he regarded Humbert as a monster. He wasn’t celebrating Humbert’s perversion. Humbert as narrator also regards himself as a monster. He refers to himself as a spider, some kind of odious animal, an “Oriental” potentate taking sexual advantage of the youngest and most helpless of the girls in his harem, and many other extreme images. So the novel really condemns him. The tricky thing is that there’s something very engaging about Humbert at the same time. He’s a brilliant writer, he’s witty, he’s cultivated, he’s self-ironic. As you read, you have to balance these two things—that Humbert Humbert is an odious figure who’s done irreparable harm to this young girl, and that there is something compelling and entertaining about him, something seductive, you might say. Nabokov was interested, among other things, in the way art could twist people. Humbert says at one point that he is a poet à mes heures (“in my leisure time”), and there’s a model of poetry behind the whole setup of Lolita—the Western literary tradition going back to the Renaissance and Dante and Petrarch of the beautiful young woman as a model and inspiration for the poet’s work. And that is what’s going on in Lolita in a perverse form.

I read Lolita when it first came out, in the 1950s. Obviously, the climate has shifted a lot on these issues. In fact, the head of a leading London publishing house said a couple of years ago that if the manuscript were submitted to him now, he would not publish it. I don’t know whether he came to that conclusion because he thought it was an immoral or obscene book or whether he simply feared the reader response.

If Lolita were banned, or had never been published, the first thing that we’d be missing is one of the most splendid exhibitions of English style in an American novel written in the 20th century.

And if you’re a word junkie, as I am, that’s something you don’t want to give up. But also, what’s really going on in the novel is a probing and even moving representation of a man who is trapped in his own obsession, causing great harm and unable to break free of it. He wants to—Humbert mentions several times that he has spent a period of months in a psychiatric institution. And although the perversion is very extreme, there might be many thousands or millions of people who are trapped in their own neuroses or obsessions, not necessarily as extreme as Humbert’s, but the general situation of being a prisoner of your obsession or your neurosis or psychosis is an aspect of life that’s not unusual.

I don’t think my own life would have been materially different if I hadn’t been able to read Lolita. But I am a person who puts a very high value on art, as Nabokov did. Art is something that transforms and enriches our lives in some essential way. And reading Lolita for the first time—of course, I’ve read it several times over the years—there was this revelation of the magical quality of brilliant prose, which is something that I’ve been thinking about, and deeply admiring, ever since, not only in Nabokov but in Melville and Faulkner and all kinds of other writers, many of whom I’ve spent my career teaching.

Nabokov certainly affected how I looked at literature and how I taught it. Although the subject matter of Lolita is pretty grim, there is an element of playfulness in Nabokov’s writing combined with moral seriousness, and that lit up for me a whole dimension of literature. Can contemporary readers still find this kind of value in it? I think so.

Robert Alter is a professor emeritus of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley. He is the author of numerous books, including a complete translation of the Hebrew Bible.

[Read: “The ‘Maus’ Trap: Famous Banned Books by Jewish Authors”]

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.