In a recent interview, Kristen Bell and Adam Brody revealed that their new Netflix show, Nobody Wants This, about a rabbi who falls in love with a non-Jewish woman, was originally titled Shiksa. The word shiksa has a long and complex history, but some consider the word, often used derogatorily, to be a slur. This 2006 article explores shiksa’s historical usage, from its roots in Eastern Europe to its use in classic American literature and television.

To see this article in its original context, click here.

She’s a Jewish mother’s worst nightmare and a Jewish man’s Gentile goddess. Shiksa, the Americanized version of the Yiddish shikse, derives from the Hebrew shekketz, meaning “abomination of and referring in the Torah to idolatry and unclean food. The Talmud cautions, “Let him not marry the daughter of an unlearned and nonobservant man, for they are an abomination [shekketz] and their wives a creeping thing.” Shikse’s more modern roots are as the female spin-off of the Yiddish sheygets, a non-Jewish male whose plural schotsim is close in sound to the Hebrew shikkutzim—”abominations.”

The origins of the word shiksa

Back in Eastern Europe, as Dovid Katz, a professor of Yiddish at Vilnius University, explains, shikse’s primary use was as a slang word among Jewish men for “a sexually attractive, young, non-Jewish female.” It was strictly an inter-Jewish word, which, like other Jewish words for Gentiles, was not shouted at cute Polish girls passing by. Its second, more serious use, as Katz notes, was “meant religiously—someone married a shikse” Michael Wex, author of Born to Kvetch, brands shikse as an early Yiddish weapon in the “unending war against mixed dating. The idea is that these are attractive people, so if you call them slimy, it kind of takes some the attraction out of it.” Jewish mothers tried to further spoil the allure by reminding their sons that “a yonge shikse vert an alte goye.” In other words, as Wex explains, the young shikse turns into an old, Gentile hag. And finally, parents used the word as a mild rebuke to mischievous girls. “In traditional Jewish folklore, a parent must never scold a child with something that she or he might become. So traditionally, it is okay, in anger, to call a child a sheygets or a shikse because it can never become that,” says Katz.

The folks at Miriam-Webster’s Dictionary date the appearance in America of shiksa—with an “a” as opposed to an “e” at the end—to 1872, and the word received its spot in the dictionary in 1961. Though both sheygets and shikse were popularly used in Eastern Europe, sheygets is rarely heard today in the United States. One explanation for this is that until recently, it was predominantly Jewish men who intermarried and, given Judaism’s matrilineal descent, a shiksa posed a greater assimilationist threat than did a sheygets. Diane Wolf, a professor of sociology at University of California at Davis, believes that the real reason for the word’s persistence is “just general misogyny and sexism that allows terms that are derogatory towards women to be perpetuated much more so than terms that are derogatory towards men.” For a Jewish parallel, Wolf points to numerous references to JAPs—Jewish American Princesses—and the glaring absence of Jewish American Princes.

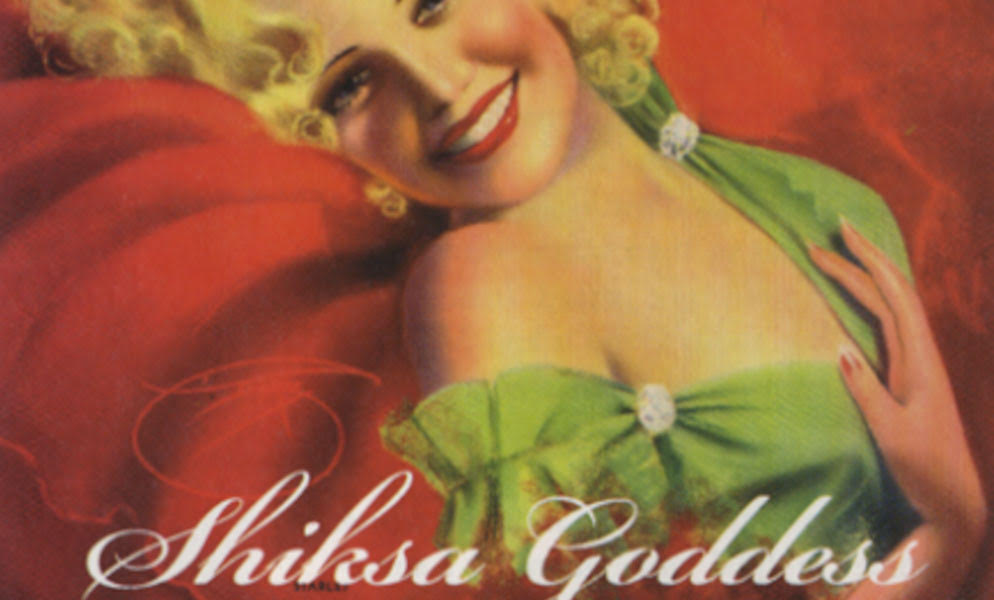

Whatever the reason, the idea of the shiksa has thoroughly infiltrated American culture. The “blatantly shikse” baton-twirling Alice Dembosky and “all her dumb, blond, goyische beauty” are described head to toe in Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint. The late Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Wendy Wasserstein humorously chronicles her New York City life in Shiksa Goddess: Or, How I Spent My Forties. In Barbara Baitlett’s novel, The Shiksa, former Catholic school girl Katherine Winterhaus unsuccessfully battles her “shiksa syndrome” of falling in love with Members of the Tribe. Perhaps no single event did more to popularize the word among Gentiles than the airing of the 1997 Seinfeld episode in which Jewish men—from bar mitzvah boy to rabbi—go crazy for shiksa Elaine Benes, played by the Jewish actress Julia Louis-Dreyfus. “You’ve got shiksappeal. Jewish men love the idea of meeting a woman that’s not like their mother,” explains George Costanza to the bewildered brunette. In HBO’s hugely popular Sex and the City, the prim and proper Park Avenue “shiksa goddess” Charlotte Yorke converts to Judaism to marry her former divorce attorney and fling Harry Goldenblatt.

Is the word shiksa offensive?

Whether it is ignorance about the word’s negative connotations, an attempt to turn the tables on them, a bit of Jewish and Gentile humor or some combination of all of the above, shiksa is undergoing a revival. Kristina Grish, the 30-year-old author of Boy Vey!:The Shiksa’s Guide To Dating Jewish Men says that, ‘To our generation, using the word shiksa is equivalent to wearing a Phil Collins t-shirt— pure irony. It might be compared to how feminists embraced the word ‘bitch’ in the 70s.” Sara Schwimmer, the 29-year-old founder of Chosen-Couture.com, has cashed in on the word’s newfound trendiness by creating a SHIKSA T-shirt, a hit with Jews and Gentiles alike. “If anything, I think people find it more amusing than they do offensive. We certainly get a lot of women buying it for themselves,” says Schwimmer.

Christine Benvenuto laments shiksa’s popularity and longs for the word’s eventual demise. As Benvenuto, author of Shiksa: The Gentile Woman in the Jewish World, puts it, “I wish it would die out, but really doesn’t seem to be dying out. It’s sticking around, particularly with young women seeming to find it a sexy word to use at themselves. It seems to have a whole new life.”