By Symi Rom-Rymer

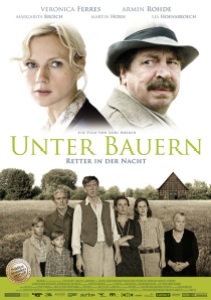

Those seeking a Holocaust movie rendered in bold strokes of black and white, where the distinction between good and evil is clear and unwavering, will not find it in “Saviors in the Night;” the opening film of this year’s New York Jewish Film Festival. Directed by Ludi Boeken and based on the 1967 memoir of Marga Spiegel, this film seeks to tell multiple complex stories at once and where there are no clear heroes.

Those seeking a Holocaust movie rendered in bold strokes of black and white, where the distinction between good and evil is clear and unwavering, will not find it in “Saviors in the Night;” the opening film of this year’s New York Jewish Film Festival. Directed by Ludi Boeken and based on the 1967 memoir of Marga Spiegel, this film seeks to tell multiple complex stories at once and where there are no clear heroes.

The film begins with a brief prologue: Deep in the muddy trenches of World War I four young, exhausted men in dirty German uniforms help each other flee to safety in the wake of a gas attack. One of those men is Siegmund “Menne” Spiegel, a decorated Jewish soldier who now, 25 years later, must seek the help of his wartime friends when he and his family are in imminent danger of deportation.

He first turns to Heinrich Ashloff, a farmer in a small village in Westphalia, who agrees to hide Menne’s wife (Marga) and daughter (Karin) but refuses to shelter Menne because his face is too familiar to the other villagers. Abandoned, he is forced to flee from barn to attic as he tries to find shelter with other friends and acquaintances.

This film, however, doesn’t simply present a unidimensional description of the trials of a Jewish family during the Holocaust. Atypically, it also focuses attention on the trials of German families during World War II. We see the toll of the war through the departure of the oldest Ashloff son for the Eastern Front and the resulting uncertainty and fear etched into the faces of those he leaves behind. We also see the brutality and humiliation that the SS unleash on their fellow Germans as end of the Nazi reign draws nearer.

Equally unusual, are Boeken’s flawed portrayals of Heinrich Ashloff and Marga Spiegel, the film’s true protagonists. Heinrich incorporates Marga and Karin into his life, protects them at all costs, and eventually come to see mother and daughter as part of the family. Yet he has not entirely avoided the influence of Nazi ideology. He refers to Menne as having a “Jew-face” and emphasizes his loyalty to Hitler to his daughter, Anni, reminding her that he joined the party in 1930 believing that Hitler would be good for Germany and famers (despite his virulently anti-Jewish rhetoric). Marga, too, is allowed her struggles and moments of weakness. Despite her deep appreciation of and friendship for the Ashloff family, she calls openly for the destruction of Germany and Germans in front of them. More dangerously, due to forgetfulness and occasional lack of composure she puts her life, and those of the sheltering family, at great risk several times.

Indeed, it is the way “Saviors in the Night” allows for nuance and complexity in its non-Jewish characters as well as in its Jewish ones that sets this film apart from typical Holocaust movie fare. Poignantly drawn characters are revealed to us in all their complicated humanness. The side-by-side stories of Germans and Jews do not ask us to equate or elevate the suffering of one group over another, but rather considers each part of a larger, messy whole.

In the epilogue, we discover that Marga and Anni remained in touch after the war and remain close friends at 97 and 88 years-old respectively. That is surely the greatest conclusion of all.

Symi Rom-Rymer writes and blogs about Jewish and Muslim communities in the US and Europe. She has been published in JTA, The Christian Science Monitor and Jewcy.