Reframing Roman Vishniac’s Legacy

by Diane M. Bolz

Maya Benton was a high school senior living in Los Angeles when the Russian-American photographer Roman Vishniac’s first posthumous book, To Give Them Light, came out in 1993. Renowned for his iconic images of Eastern European Jews taken between the two World Wars, Vishniac had died three years earlier at age 92. One particular photograph in the volume struck a powerful chord with Benton’s family. “The Photograph,” as Benton (now a curator at New York City’s International Center of Photography) calls it in her introduction to the recently published, 384-page monograph Roman Vishniac Rediscovered, depicted a lone signpost. It was one of the thousands of images taken by the photographer from 1935 to 1938 on an assignment to document Jewish life in Eastern Europe. Among the various signs mounted on the post was one that read “Nowogrodek”—the town from which Benton’s grandparents had fled in 1941, when it was overrun by the Nazis.

The publication of that image marked the beginning of Benton’s engagement with Vishniac’s work. It was an interest she pursued while a graduate student at Harvard and one that ultimately led her to an extensive archive of Vishniac’s photographs in the possession of his daughter, Mara Vishniac Kohn. That trove—some 50,000 items, including vintage prints, rare film footage, contact sheets, personal correspondence and nearly 10,000 negatives—was subsequently acquired by the International Center of Photography (ICP). Benton’s research in that archive led to the center’s exhibition “Roman Vishniac Rediscovered,” which premiered in 2013 and is now on view through May 29 at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco. Benton curated the show and edited the comprehensive monograph.

The exhibition, she says, embodies a reappraisal of Vishniac’s total body of work—from his Berlin street photography of the 1920s and early 1930s, through his portraiture and documentary images of the postwar period in America, to his groundbreaking efforts in color photomicroscopy (photography through a microscope) of the 1950s to 1970s. A versatile, prolific and innovative photographer whose career spanned more than five decades, Vishniac brought his Rolleiflex and Leica cameras, along with his eye for bold composition, to such diverse subjects as stylish pedestrians on cosmopolitan streets, Orthodox Jews in rural villages, performers in New York nightclubs and children in displaced persons camps. For those who are familiar only with Vishniac’s widely published images of Eastern European Jews, the exhibition and book will be a revelation. “The vast holdings of the Roman Vishniac Archive,” says Benton, “have allowed us to reposition Vishniac as one of the great photographers of the 20th century.”

Vishniac’s 7-year-old daughter, Mara, stands in front of an election poster for Hindenburg and Hitler in Berlin in 1933.

Vishniac was born in 1897 to a well-to-do Jewish family in the Russian town of Pavlovsk, outside St. Petersburg, and grew up in Moscow. Fascinated as a child by biology and photography, Roman was given his first camera and microscope at age seven. In 1918, the family immigrated to Berlin following the Bolshevik Revolution, but 21-year-old Roman remained in Moscow to pursue graduate studies in biology and zoology. He joined his parents in 1920, along with his new Latvian wife, Luta Bagg. Vishniac built a fully equipped photo-processing laboratory in the couple’s Berlin apartment and continued to pursue scientific research and microscopy while also becoming a skilled street photographer. The couple’s two children, Wolf and Mara, were born in Berlin.

Vishniac’s photographs of Berlin from the 1920s and early 1930s, with their dramatic play of light and shadow and diagonal lines, reveal a modernist sensibility. They also capture an atmosphere of foreboding. As swastika banners, campaign posters and signs of militarization became more and more visible across the city, Vishniac would often pose young Mara in front of posters or shop windows to divert attention from his intended subjects. During this period, he was hired to document the work of Jewish community and social-service organizations in Berlin.

From 1935 to 1938, he was commissioned to record Jewish life in Eastern Europe (especially religious and impoverished communities) by the European headquarters of the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) as part of their campaign to raise relief funds. Over a period of four years, Vishniac covered some 5,000 miles—from remote areas of Carpathian Ruthenia to central Warsaw. In 1938, while photographing thousands of Jewish refugees expelled from Germany and trapped in the small Polish border town of Zbaszyn, he took a picture of a young girl by the name of Nettie Stub. The photograph was picked up by the Red Cross, which later rescued the girl and brought her to safety in Sweden.

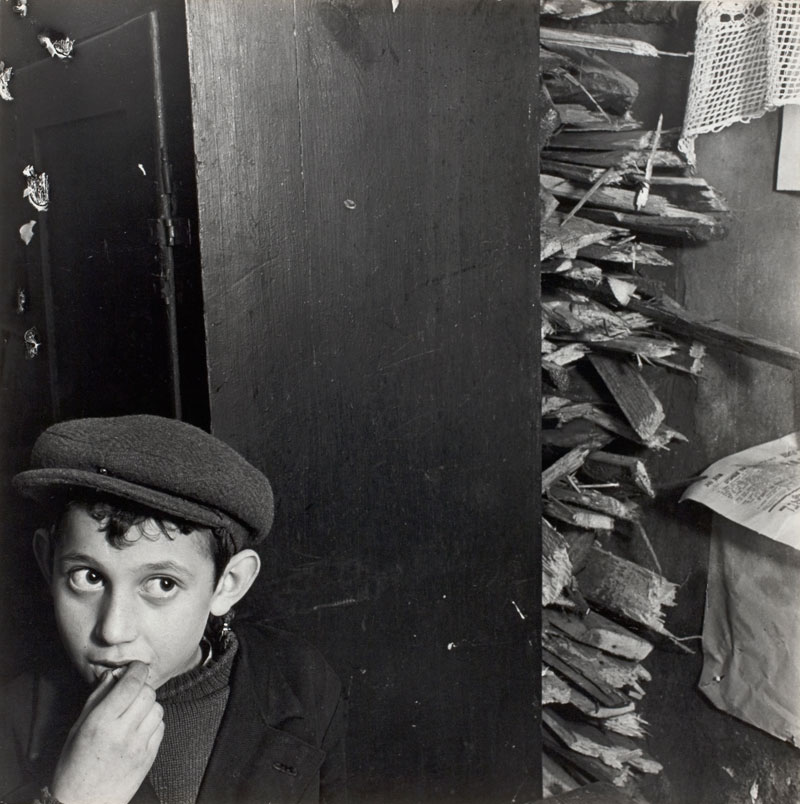

One of the many photographs Vishniac took c.1935–38 on assignment from the JDC catches a boy and kindling in a basement on Warsaw’s Krochmalna Street.

While working as a freelance photographer in France in 1939, Vishniac was arrested and briefly imprisoned in a French detention camp. Meanwhile, his wife had managed to get visas for the family to immigrate to the United States via Lisbon. After his release, Vishniac joined his wife and children in Lisbon, and on New Year’s Eve 1940, the family arrived in New York City. Vishniac opened a portrait studio on the Upper West Side to support his family and was able to parlay his connections with the Russian and German Jewish expatriate communities to obtain such famous subjects as Marc Chagall, Albert Einstein and Yiddish theater star Molly Picon. During the 1940s, he also turned his lens on Jewish community life in New York and the arrival of Jewish refugees.

In 1946, Vishniac became an American citizen, and he and Luta divorced. The following year, he was sent to Europe on an assignment from the JDC, the United Jewish Appeal and The Forward to document relief efforts in Jewish displaced persons camps in Germany and France. Stopping in Berlin, he connected with an old friend, Edith Ernst. They married and remained together until his death in 1990. While in Berlin, he took a series of poignant photographs of the ruins of the city he had once called home. Seen for the first time in this exhibit and book, they provide a highly personalized view of postwar life in Berlin.

For the last half of his life, photomicroscopy became Vishniac’s primary focus. He established himself as a pioneer in the field by developing innovative techniques to capture images of the microscopic world. These unique photographs appeared in numerous articles and on dozens of magazine covers.

A boy stands on a mountain of rubble in postwar Berlin in a previously unpublished 1947 image.

Holocaust survivors gather outside a building where matzah is being made for Passover in a displaced persons camp in Picardy, France, 1947.

The current exhibition and its accompanying monograph reveal the breadth and diversity of Vishniac’s vision. They also provide insight into and a new perspective on Vishniac’s iconic photographs of Eastern European Jewry by placing them within the context of his entire body of work and the broader tradition of 1930s social documentary photography. His widely published images mainly depict privation—families suffering from dislocation, crowded living conditions and deprivation. His previously unpublished work, uncropped images and contact sheets present a more complex and nuanced view of Jewish life.

The commission from the JDC—to photograph “not the fullness of Eastern European Jewish life, but its most needy, vulnerable corners for a fund-raising project”—clearly had an impact on Vishniac’s editing process. It also likely influenced his captioning, which has been criticized for being exaggerated and, in some instances, fabricated. In her research, Benton came across certain inconsistencies and contradictions. A young girl in one image, for example, whom Vishniac noted could not go outside because she owned no shoes, turns up in another photo wearing shoes. With the end of the war and the full scope of the Holocaust revealed, Vishniac’s photographs took on a larger, more symbolic meaning. In that altered context, they became an elegiac record of a vanished way of life—a final photographic documentation of a world on the brink of extinction. Vishniac’s books and exhibitions propagated that vision. The current exhibition and book present a broader, more balanced view of that world.

In 2012, Vishniac’s negatives were digitized by the ICP and are now available to the public on a digital database shared with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Benton views this database, the exhibition and monograph as only “the beginning of the conversation about Vishniac and his life’s work” and hopes it will serve as a catalyst for future research. —Diane M. Bolz