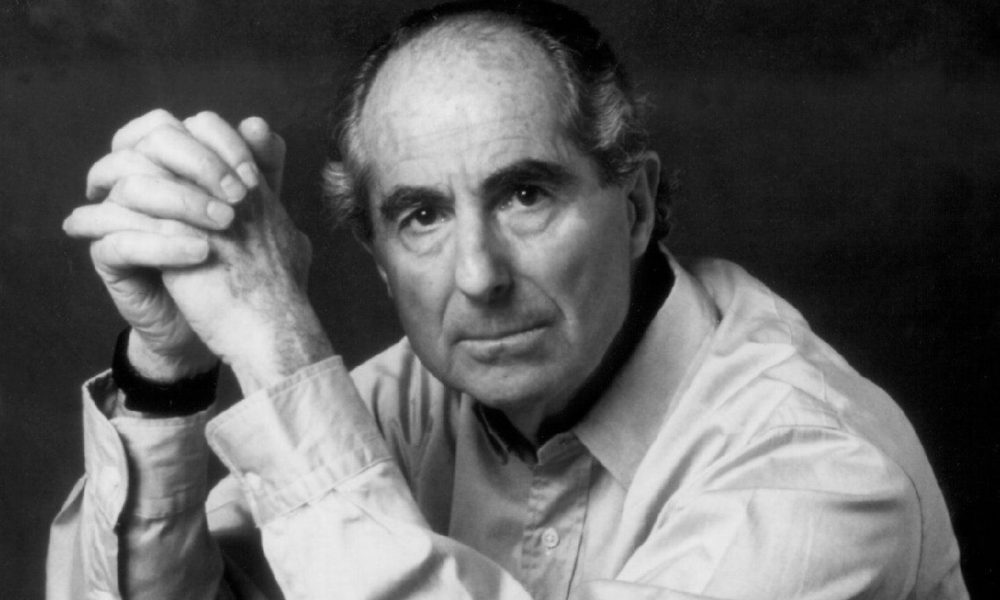

Over the course of his remarkable career, Philip Roth received nearly every literary award imaginable. One of these prizes was an honorary doctorate from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, which he received in May 2014. The JTS degree, though, was not merely one more feather that Roth added to his magnificent literary cap; it marked the beginning of a long overdue reconciliation between a writer and his people. Now that our inimitable literary lion—our contemporary Kafka—has passed, the time has come for the rest of the Jewish people to follow suit and atone for our modern-day original literary sin.

Like his novel The Ghost Writer, Roth’s autobiographical work of nonfiction The Facts recounts how a certain slice of the Jewish community repudiated Roth and indignantly accused him of “airing their dirty laundry.” In 1962, Roth was heckled when speaking at Yeshiva University. He was not the first literary eminence to experience such derision—Albert Camus was heckled shortly after he was awarded the Nobel Prize—nor, unfortunately, will he be the last. Nevertheless, this unwarranted invective was so bitter that Roth vowed to never write about Jews again.

Even though he returned to writing about Jews with a vengeance several years later, that Roth still smarted over this incident indicates that it was—at least in part—the source of the unrepaired rupture between the writer and his people. Jews denounced Roth for the same offense for which Nathan Zuckerman was castigated by his father in The Ghost Writer: “Do you fully understand what a story like this story, when it’s published, will mean to people who don’t like us?” Whether or not Roth understood what his stories portended for the Jews, Jewish martinets failed to grasp Roth because they did not yet understand that radical freedom is a writer’s lifeblood. And because of his desire for radical freedom, Nathan had to free himself from his father—much as Roth needed to escape his ethnic and religious patrimony—if he wished to become a writer who was truly unbound.

Roth’s first four stories (“The Conversion of the Jews,” “Epstein,” “Eli, the Fanatic” and “Defender of the Faith”) and his first novella (Goodbye, Columbus) set the stage for Roth’s career-long cantankerous relationship with the American Jewish community. To say that Roth’s first four stories were not received favorably by the literati of the American Jewish community would be an understatement; many American Jewish literary bien pensants believed that Roth was being deliberately, and unfairly, provocative. The story “The Conversion of the Jews,” about a young Hebrew school student who uses his prone position on the edge of the synagogue roof to pressure all those watching him into professing faith in Jesus Christ, could have easily, and understandably, been construed as inflammatory. But it was two other stories, which on their surfaces were more innocuous than “The Conversion of the Jews,” that triggered the real indignation of the American Jewish community: “Epstein” and “Defender of the Faith.”

“Epstein,” the story of an adulterous Jewish man, was viewed critically by Roth’s Jewish readers. Roth received a letter from a Detroit man asking why it was necessary for Roth to portray a Jewish man as an adulterer. “Why so much shmutz?” the man asked. David Seligson, a New York rabbi writing in The New York Times, called Roth “narrow-minded” for his seemingly single-minded focus on sexuality—a charge that would foreshadow a criticism which would plague Roth throughout his career. Seligson charged the Newark-born writer with devoting himself to “the exclusive creation of a melancholy parade of caricatures.”

“Defender of the Faith,” a story about a Jewish army recruit who attempts to gain certain privileges and favors from his Jewish sergeant by appealing to his sergeant’s Jewishness, raised the ire of American Jewish rabbis to an even further degree. Though Alfred Kazin reviewed the story favorably, other Jews were not as kind. Whereas Roth’s earlier stories had been published in The Paris Review, whose readership was small, and in Commentary, whose readership was comprised mostly of Jews, “Defender of the Faith” was published in 1959 in The New Yorker, whose circulation was significantly larger than that of The Paris Review. And unlike Commentary, The New Yorker’s readership was comprised mostly of non-Jews. This fact proved problematic for Roth’s Jewish readers; following the story’s publication, letters were sent to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) objecting to the story’s publication, and Roth received a letter from a rabbi who wrote: “your story—in Hebrew—in an Israeli magazine or newspaper would have been judged exclusively from a literary point of view.” But because it had been published in an American magazine and would be read by non-Jews, Roth was engaging in one of the worst possible crimes a Jew could commit against a fellow Jew: “informing,” the rabbi wrote. The rabbi analogized Roth’s publishing “Defender of the Faith” in The New Yorker to shouting “Fire!” in “a crowded theater,” and indicted Roth for neglecting what had historically been the question that no Jew conscious of anti-Semitism should ever neglect whenever doing or saying anything in public: “What will the goyim think?”

Other reactions to “Defender of the Faith” were no less kind. Jewish readers were worried that Roth was perpetuating medieval stereotypes of Jews as clannish and unethical, and they fretted that the story would stoke the flames of anti-Semitic fires that American Jews, for the most part (at least in comparison to their European ancestors and contemporary European counterparts), had been able to avoid. A Jewish reader wrote to Roth:

Mr. Roth:

With your one story, “Defender of the Faith,” you have done as much harm as all the organized anti-Semitic organizations have done to make people believe that all Jews are cheats, liars, connivers. Your one story makes people—the general public—forget all the great Jews who have lived, all the Jewish boys who served well in the armed services, all the Jews who live honest hard lives the world over…

Another Jewish layman wrote to The New Yorker:

Dear Sir:

…We have discussed this story from every possible angle and we cannot escape the conclusion that it will do irreparable damage to the Jewish people. We feel that this story presented a distorted picture of the average Jewish soldier and are at a loss to understand why a magazine of your fine reputation should publish such a work which lends fuel to anti-Semitism.

Nastiest of all was a rabbi—an unidentified New York City rabbi who, according to Roth, was “a man of prominence in the world of Jewish affairs”—who wrote the following to the ADL:

Dear —,

What is being done to silence this man? Medieval Jews would have known what to do with him…

But was Roth really the “Jew who got away,” as Nathan Zuckerman wonders about E. I. Lonoff in The Ghost Writer? Absolutely not. Roth, as Lonoff replies to Zuckerman, may have been the “Jew who got away,” but he “didn’t get away altogether.” In fact, his entire literary career has been surprisingly, authentically, Jewish.

No Jew aired more dirty laundry than the prophet Isaiah; in a verse that evokes Potok’s Asher Lev’s stinging critique of his father’s “aesthetic blindness,” Isaiah called us a people of “unclean lips,” “fattened hearts,” “heavy ears” and “sealed eyes.” The prophet Jeremiah called us the people of “uncircumcised ears,” and that was his mildest malediction. Yet our prophets were no more concerned with what their poetry would mean for the Arameans than Roth was concerned with what his prose augured for Americans. By airing our dirty laundry like Isaiah and Jeremiah, by serving as the amanuensis of our collective psyche, and by crafting novels whose leitmotifs are redemption and life, Roth—though never in the “virtue racket”—arguably came closer to authentic Jewish writing than any other writer has in a very long time.

Judaism’s eponymous ancestor is not the saintly Joseph who resisted the adulterous temptations of Potiphar’s wife; it is Judah, who solicited a prostitute that turned out to be his daughter-in-law in disguise—she was desperate for children after Judah’s sons Er and Onan spilled their seed (hence the term) rather than ruin her beauty by impregnating her. Our greatest hero—King David—a libidinous leader of a nation at war, could not keep his pants on once Bathsheba came into his field of vision. Our eventual Messiah, Jewish tradition teaches, will descend from the product of a drunken, incestuous bacchanal between Lot and his daughters. According to the pious Rabbi Akiva of the Talmud, our holiest biblical book is The Song of Songs, an erotic love poem that verges on the pornographic. And our greatest prophet, Moses, who received the Ten Commandments on Sinai—the only prophet to ever “know God face-to-face”—married a non-Jew, Tziporah the Midianite, only to be criticized by his sister Miriam for not sleeping with her. Doc, our Bible is a Jewish joke!—and we are IN it!

These lascivious stories were not written by Alex Portnoy or Nathan Zuckerman—hard as this may be to believe—but are found in an anthology of ludic mastery that, even more than the works of Bellow, Kafka and Malamud, is Roth’s authentic literary precursor: the Hebrew Bible. Our sacred scriptures air laundry that is dirtier and more shameful than Alexander Portnoy’s dirtiest shame-filled socks. For Jews, it is the Bible—not Roth—that is a greater source of collective embarrassment.

“Thou shalt be holy,” commands the Bible in Leviticus, but like Roth in The Human Stain, our scriptures never lose sight of the elemental humanity—our rampant, incorrigible penchant for unholiness—that unifies us all. One of our most well-known Talmudic legends, in which the rabbis subtly excoriate Pharaoh for attempting to maintain an aura of divinity by performing his bodily functions in secret, is a proto-Yeatsian affirmation of the body. The Human Stain’s disquisition on life’s “shameless impurity”—“How can one say, ‘No, this isn’t part of life,’ since it always is? The contaminant of sex, the redeeming corruption that de-idealizes the species and keeps us everlastingly mindful of the matter we are”—may as well have been written by the Talmudic sages. The Jewish Bible, just as much as Roth, explores what Roth termed “the folly of sex,” and Kind David, just as much as Nathan Zuckerman, illuminated “the intolerable disorder of virile pursuits” and “the enlivening anarchy that overtakes anyone who even sparingly abandons himself to uncensored desire.”

So, is Roth “the writer who got away from us”? Hardly. We are the people who got away from Roth.

Philip Roth does not need our forgiveness as much as we need his, and now it must come posthumously. “What is the rite of purification? How shall it be done? By banishing a man, or expiation of blood by blood,” warns Sophocles’s Oedipus the King, a quotation Roth used as The Human Stain’s epigraph. Jewish law decrees that one must beg forgiveness from a person one has wronged up to three times. Our moment of peripeteia has arrived; for those of us in the Orthodox community, it is time to end our hubristic banishment of Roth, cease our tempting of the fates and request expiation for this stain upon our collective conscience. Let Roth resume his rightful place in the canon of Jewish literature—alongside the Talmud, the Kabbalah and the other great works of the Jewish literary imagination. And let the wild rumpus begin again.

Daniel Ross Goodman is a writer, rabbi and Ph.D. candidate at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, and is studying English and comparative literature at Columbia University.